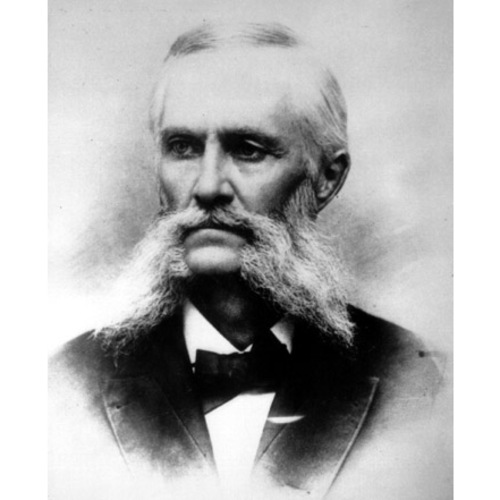

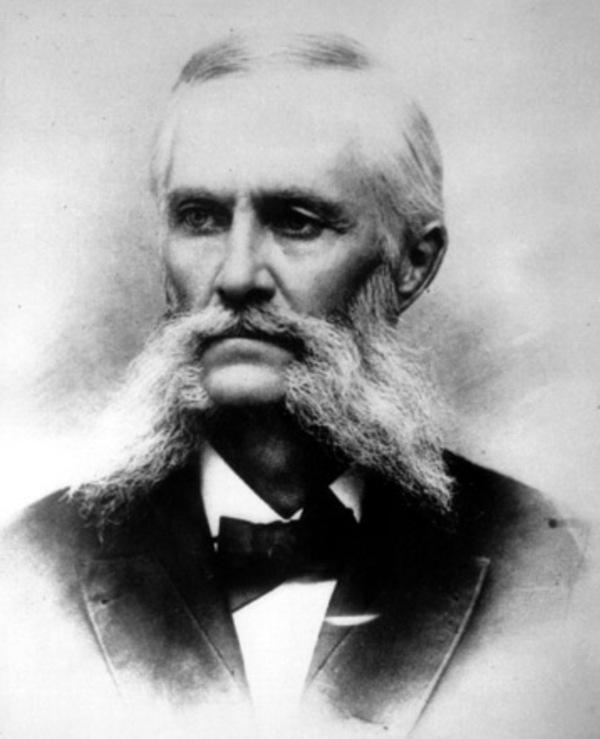

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

ROGERS, ALBERT BOWMAN, civil engineer; b. 28 May 1829 at Orleans, Mass., son of Zoar Rogers and Phebe S. Kenrich; m. first in 1857 Sarah Lawton (d. 1858) of New York; m. secondly Nellie Brush of Iowa; d. 4 May 1889 at Waterville, Minn.

As a young man, Albert Bowman Rogers was apprenticed to a ship’s carpenter but made one sea voyage only. He entered the engineering faculty at Brown University in 1851 and after transferring to Yale the next year obtained his bachelor’s degree in 1853. Following graduation he was employed as an engineer on the Erie Canal, before moving to Iowa and then to Minnesota. In 1862 he was commissioned major in the United States cavalry by the governor of Minnesota, Alexander Ramsey, during the uprising of the Dakota Sioux. The year before, he had joined the engineering staff of the Chicago, Milwaukee and St Paul Railroad, where he earned the nickname “The Railway Pathfinder” for his location work. This brought him to the attention of James Jerome Hill* of St Paul, a member of the executive committee of the Canadian Pacific Railway. Hill hired him in late February 1881 to take charge of all mountain location work for the company.

Rogers’ main task was to find and locate two passes, through the Rockies and the Selkirk Mountains, which would provide the CPR with a direct route to the Pacific. In April he dispatched survey parties to work their way up the Bow River from Fort Calgary and explore both the Howse and the Kicking Horse passes in the Rockies. Rogers intended to tackle the Selkirks himself, since it was generally held that no pass existed through those mountains. He had studied the report of Walter Moberly, a British Columbia government engineer who, in 1866, had sent one of his men up the west slope of the mountains along the route of the Illecillewaet River in the hope of finding a pass. The trip proved abortive; Moberly did not believe a pass existed. But Rogers, together with his nephew Albert and a party of Kamloops indigenous people, followed the same route towards the summit of what was later named Mount Sir Donald. From this vantage point, in late June 1881, Rogers thought he saw a way through the barrier. He could not be certain because he had run out of supplies and was not able to explore the intervening 18 miles. None the less, he reported, in his enthusiasm, that a practicable route existed.

Rogers was determined to find the pass, which Hill had promised to name after him. “His driving ambition was to have his name handed down in history,” his friend, the packer Thomas Edmonds Wilson*, said of him. “For that he faced unknown dangers and suffered privations.” “To have the key-pass in the Selkirks bear his name was the ambition he fought to realize.”

In the summer of 1881 Rogers located the line through the Kicking Horse Pass. The following May he again attacked the Selkirks, this time approaching from the east by way of the Beaver River at its junction with the Columbia. Again he ran out of supplies and was forced to turn back. On 17 July he tried again, following the Beaver and its tributary the Bear to reach, at last, the same mountain-ringed meadow he had observed from the slopes of Mount Sir Donald the previous June. Henceforth, this would be known as Rogers Pass. The date was 24 July 1882.

Rogers was a controversial figure, a tobacco-chewing, hard-swearing eccentric who made many enemies through his irascibility and his parsimonious method of feeding his men, and also through jealousy, especially among those Canadian engineers who were irritated by the presence of an American rival. Marcus Smith, in charge of construction in British Columbia, thought Rogers “a thorough fraud”; Charles Æneas Shaw, another colleague, echoed that estimate. A. E. Tregent, who worked for him in the Rockies, called him “a queer man, lots of bluff and bluster.” To John Frank Stevens, one of his assistants, he was “a monomaniac on the subject of food.” On the other hand, George Monro Grant*, who with Sandford Fleming* was sent to oversee Rogers’ work in the summer of 1883, was high in his praises. “Not one engineer in a hundred would have risked, again and again, health and life as he did,” Grant wrote. Rogers’ companion, Tom Wilson, felt that he was much misunderstood: “He cultivated a gruff manner to conceal the emotions that he seemed ashamed to let anyone sense.” William Cornelius Van Horne*, the CPR’s general manager, while admitting that Rogers was “somewhat eccentric and given to ‘burning brimstone,’” also felt that he was “a very good man on construction, honest and fair dealing.”

Hill swore by Rogers, and when the CPR was completed in 1885 (Rogers was present at the driving of the last spike at Craigellachie), Hill hired him as a locating engineer on what would become the Great Northern Railroad. Rogers’ career ended in 1887 when, at work for Hill in the Cœur d’Alene Mountains of Idaho, he was badly injured falling from his horse. He died two years later at the home of his brother in Waterville, Minn., after a long and painful illness from cancer of the stomach.

Canadian Pacific Arch. (Montreal), Letters from A. B. Rogers. Glenbow-Alberta Institute, T. E. Wilson and W. E. Round, “The last of the pathfinders” (1929); pub. as Trail blazer of the Canadian Rockies, ed. H. A. Dempsey (Calgary, 1972). Minnesota Hist. Soc. (St Paul), Cannon River Improvement Company papers; Scrapbooks, 2. PABC, Add. mss 767, Marcus Smith to Joseph Hunter, 23 Feb. 1885. PAC, MG 28, III20, 1, C. Van Horne letterbook, no.1: 234–40; 2, C. Van Horne letterbook, no.7: 483–85.

B.C., Lands and Works Dept., Columbia River exploration, 1865–6: instructions, reports, & journals . . . (2v. in 1, Victoria, 1866–69), II: 15. A. L. Rogers, “Major A. B. Rogers’ first expedition up the Illecillewaet valley, in 1881, accompanied by his nephew, A. L. Rogers: an account of the trip,” A. O. Wheeler, The Selkirk range (2v., Ottawa, 1905), I: 417–23. G. M. Grant, “The C.P.R. by the Kicking Horse Pass and the Selkirks – X: the Rogers’ Pass,” Week (Toronto), 1 May 1884. Winnipeg Daily Times, 23 Jan. 1882. Obituary record of graduates of Yale University deceased from June, 1880, to June, 1890 . . . (New Haven, Conn., 1890), 535–36. Pierre Berton, The national dream: the great railway, 1871–1881 (Toronto and Montreal, 1970); The last spike: the great railway, 1881–1885 (Toronto and Montreal, 1971). J. M. Gibbon, Steel of empire: the romantic history of the Canadian Pacific, the northwest passage of today (Toronto, 1935). J. H. E. Secretan, Canada’s great highway: from the first stake to the last spike (London and Ottawa, 1924). J. F. Stevens, An engineer’s recollections (New York, 1936); repr. from Engineering News-Record (New York), 114 (January–June 1935)–115 (July–December 1935). B. A. McKelvie, “They routed the Rockies! Railway pathfinders forged steel links from east with west,” Vancouver Daily Province, 3 Feb. 1945, magazine section. C. Æ. Shaw, “A ‘prairie gopher’ makes reply,” Vancouver Daily Province, 27 Oct. 1934, magazine section.

Revisions based on:

New York Times, 8 Aug. 1890. Poor’s manual of railroads (New York), 1909.

Cite This Article

Pierre Berton, “ROGERS, ALBERT BOWMAN,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 10, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/rogers_albert_bowman_11E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/rogers_albert_bowman_11E.html |

| Author of Article: | Pierre Berton |

| Title of Article: | ROGERS, ALBERT BOWMAN |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1982 |

| Year of revision: | 2020 |

| Access Date: | March 10, 2026 |