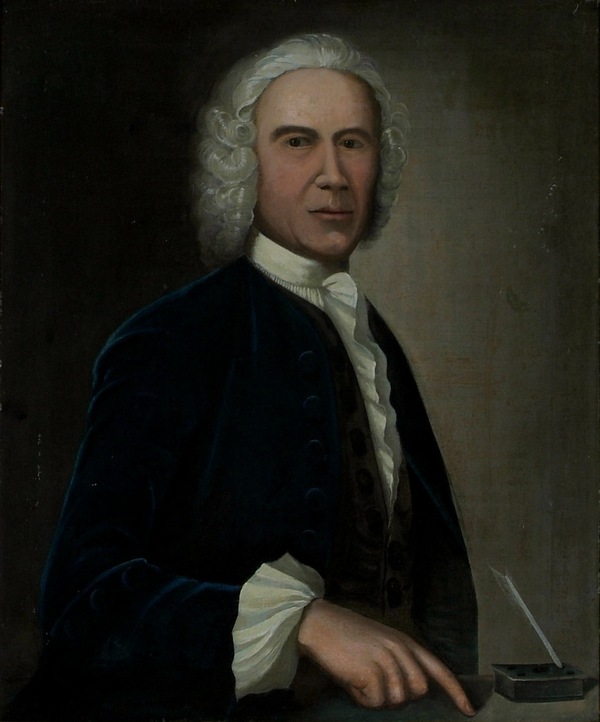

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

SALTER, MALACHY (Malachi), merchant and office-holder; b. 28 Feb. 1715/ 16 at Boston, Massachusetts, second son of Malachy Salter and Sarah Holmes; m. there on 26 July 1744 Susanna Mulberry, and they had at least 11 children; d. 13 Jan. 1781 at Halifax, Nova Scotia.

Unlike the most successful early entrepreneurs in Halifax, Malachy Salter had been born in New England and with it, rather than England, he maintained financial and emotional ties. Before settling in Halifax, perhaps as early as 1749, he had been in turn a seaman in the American coastwise trade, an associate of his uncles Nathaniel and George Holmes in their successful Boston distillery, and the senior partner in a firm involved in the fisheries and the West Indian trade. Established tradition says that he was a frequent visitor to Chebucto Bay before the founding of Halifax in 1749.

Initially in partnership with John Kneeland, also of Boston, Salter established himself as a general merchant in Halifax, where the debtors’ act protected him against the demands of the New England creditors from whom he had fled. As agent for former associates, he transacted the sale of their cargoes and sought executions in the courts for debts owed them. In his own right he engaged in shipping ventures which brought him both North American and European goods. He also extended credit, prosecuted debts, settled estates, and purchased Halifax properties, often from the over-extended poor. No doubt it was not his creditors alone who found him a “Litigious troublesome Man” “who has treated us in a Barbarous cruel manner.” In 1754 Salter expanded his operations into the remunerative field of government contracts, farming the impost and retail duties on rum and importing stock from New England to supply the Germans at Lunenburg [see Benjamin Green]. He was subsequently called upon to provide certain mercantile evaluations for the government, but he was unable to establish himself in the fruitful provisions contracts as Joshua Mauger and Thomas Saul* had done.

Having acted briefly as a constable and a clerk of the market in Boston, Salter was an early member of the grand jury in Halifax and served as a captain of militia (1761–62) and an overseer of the poor (1765–66). In 1757, in response to Governor Charles Lawrence*’s continuing refusal to call a representative assembly, he became a leader in the committee of Halifax freeholders which employed London lawyer Ferdinando John Paris to present civic complaints against the governor before the Board of Trade. When Lawrence was forced to convene an assembly in October 1758, Salter was amongst its 20 members.

In an early show of strength, the New England-dominated assembly thwarted the Council’s attempt to limit its powers of patronage and nominated Salter, with John Newton, to act as collector of the impost and excise duties, a position which afforded the incumbent a ten per cent commission on revenues collected. In 1759, as another favour of government, Salter was granted land near Fort Edward (Windsor) to qualify him as an elector there. Two years later he was appointed a justice of the peace and collector of lighthouse duties, but he soon lost the first of these offices, which was held to be incompatible with his other positions. Initially a protégé of the Massachusetts-born Jonathan Belcher, Salter fell out of favour with the lieutenant governor when he aligned himself with the New England faction of the house in opposing Belcher’s calling of the assembly late in 1761 and determination to allow the debtors’ act to lapse. He was removed from his offices in September 1762. Reinstated as collector of lighthouse duties and justice of the peace by Montagu Wilmot*, he appears to have held the first office only briefly.

For 15 years Salter sat in the House of Assembly, representing Halifax Township from 1759 to 1765 and Yarmouth Township from 1766 to 1772. Until 1769 he attended regularly and was active on many important committees. Later he participated in only one session, that of 1772, at the end of which his election in 1770 was declared invalid. As well as speaking for the New England community in the assembly, Salter represented their struggling Congregationalism both in Halifax and in Boston [see also Benjamin Gerrish].

During the Seven Years’ War Salter was owner, with other Halifax entrepreneurs, of the privateer Lawrence. With his development of a sugar-house at Halifax in the mid 1760s he joined Mauger and John Fillis as one of Nova Scotia’s three manufacturers. His sugar-house, his friendship with Fillis, and his American trade connections enabled him to capitalize upon the embargo placed on British goods by the Thirteen Colonies in the late 1760s. Despite the promise of his diversified interests, however, and despite further government contracts during Michael Francklin’s short-lived administration of St John’s (Prince Edward) Island in 1768, Salter’s circumstances at the end of the decade reflected the collapse of Nova Scotia’s boom. His financial affairs had always been precarious and in 1768 shipping and other losses overtook him. After spending two years settling his debts in Nova Scotia and New England, he was restricted by the early 1770s to operating his sugar-house himself and in 1773 to building a vessel at Liverpool that he might go to sea, as in his youth, and thus support his family.

Salter was not a self-pitying man, but rather one who trusted in that “providence which has hitherto protected and supported me.” His final years were to try his faith severely. In 1776, sailing from London, he was accused of intending English goods for Boston rather than their stated destination, Halifax. Early in 1777 he stood trial in Halifax for seditious conversation, but the jury found him innocent of any evil intent. Later the same year his brig Rising Sun was captured by Salem privateers and condemned as a prize. A prisoner in New England, Salter obtained a pass from the Massachusetts government to settle his family there. After his return to Halifax later in the year, he was accused of attempting to redeem Nova Scotian treasury notes for his Boston associates and charged with “secret correspondence” of “dangerous tendency” with the rebels. Finding himself harassed, he sailed for England, where he remained, settling business affairs, from early 1778 to early 1780. His absence stayed court proceedings against him, but from February 1778 until his death a recognizance on charges of misdemeanour was continued from term to term. Why the charges were not pressed after his return from England is not clear, but part of the explanation may be that James Brenton*, his lawyer at least in 1778–79, had become attorney general in October 1779.

John Bartlet Brebner ranks Salter among the most important entrepreneurs of early Halifax, surpassed only by Mauger and Saul. Although his early Nova Scotian career points to such prominence, in the long run Salter’s 75 property transactions and numberless court cases provided him with neither significant capital gains nor liquid assets. His shipping activities were minor compared with those of Mauger, Francklin, or his New England associates. Only briefly was he the official that Brebner notes, for in a town dependent upon the government in its civil and military roles he failed to establish himself securely within its profitable network. Nor did his efforts to make of Nova Scotia a new New England succeed finally in giving “the hand of Boston” any significant strength in the province.

Salter’s relationship to the Mauger connection is ambiguous. There is much evidence to suggest that he was not free of its economic or political entanglements. A business associate of Mauger in the 1750s and a political ally of his forces in the 1760s, he participated with Mauger’s henchmen in the establishment of government on St John’s Island in 1768. Moreover, both his intimate friends, Fillis and Jonathan Prescott, and his son-in-law Thomas Bridge were Mauger’s men. Yet in the 1770s Mauger’s agents John Butler and Brook Watson* were among Salter’s most pressing creditors, and Salter was the only leading Haligonian prosecuted during the American revolution who was not defended by Mauger’s associates. If Salter’s affairs at one time lay within Mauger’s grasp, his scepticism of Mauger, his widespread American connections, and his determination to be self-sufficient appear to have ensured his independence.

BL, Add. mss 19069, pp.50–55 (transcripts at PAC). Halifax County Registry of Deeds (Halifax), Deeds, 1753–89 (mfm. at PANS). Harvard College Library, Harvard University (Cambridge, Mass.), fms AM 579, Bourn papers, I, 137, 144; VI, 8, 57. Mass., Supreme Judicial Court (Boston), Records, 181, no.20931 (court files Suffolk, October 1727–December 1727); 310, no.47231 (court files Suffolk, July 1738-August 1738); 1265, no.170914 (court files Suffolk, 1751/52–1753). PAC, MG 11, [CO 217], Nova Scotia A, 84, pp.18ff; [CO 220], Nova Scotia B, 17, pp.116, 118, 121. PANS, MG 9, no.109; ms file, Malachy Salter, letters, 1766–73; Salter family docs., 1759–1802; RG 1, 163–65; 342, nos.77–85; RG 37, Halifax County, 1752–71; RG 39, C, 1–39; J, 1. PRO, CO 142/15 (mfm. at Dalhousie University Archives, Halifax); 217/16–27; 221/28–31 (mfm. at PAC). “Congregational churches, in Nova Scotia,” Mass. Hist. Soc., Proc., 2nd ser., IV (1887–89), 67–73. Perkins, Diary, 1766–80 (Innis). Brebner, Neutral Yankees; New England’s outpost, 254–57. W. J. Stairs, Family history, Stairs, Morrow; including letters, diaries, essays, poems, etc. (Halifax, 1906), 209–59.

Cite This Article

S. Buggey, “SALTER, MALACHY (Malachi),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 4, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 28, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/salter_malachy_4E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/salter_malachy_4E.html |

| Author of Article: | S. Buggey |

| Title of Article: | SALTER, MALACHY (Malachi) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 4 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1979 |

| Year of revision: | 1979 |

| Access Date: | February 28, 2026 |