SCOTT, AGNES MARY (Davis), journalist; b. 12 Dec. 1863 in Quebec City, daughter of Allan John Scott and Margaret Cathleen Teresa Heron; m. 29 April 1903 William Patrick Davis in Ottawa, and they had two daughters; d. 19 Nov. 1927 in Paris, France.

As a society reporter in turn-of-the-century Ottawa, Agnes Scott described vice-regal and political society with much the same flair and sense of irony displayed by contemporary writer Sara Jeannette Duncan. Scott’s witty, well-informed, and often surprisingly daring columns reveal much about the social texture of the capital during the heady early years of Wilfrid Laurier*’s prime ministership. The opening lines of Scott’s first piece for Edmund Ernest Sheppard’s Toronto weekly, Saturday Night, in the issue of 13 March 1897, eight months after Laurier’s election, illustrate her acerbic style and shrewd appreciation of the realities of power. “‘Le roi est mort, vive le roi’ has been the cry in Ottawa since June 23, and the people who hoped ‘those horrid Grits would not get in, as it would ruin Ottawa society’ have been the very first to establish an entente cordiale with the new-comers.”

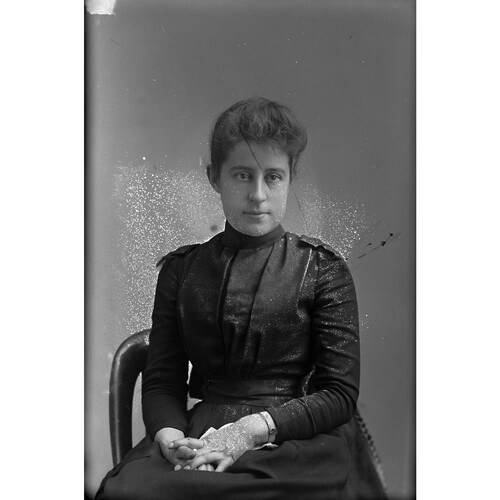

Scott herself was an integral part of that society. Her father was the youngest brother of the patriarchal Richard William Scott*, Laurier’s secretary of state; her mother was a sister of Scott’s wife. Yet she was also an outsider. Her father had died young, in 1868, and Agnes grew up in an ambience of shabby gentility in Ottawa’s Sandy Hill district, in a ramshackle house that lacked a bathroom and a furnace. A year or so after her mother’s death in 1898, she moved in with her uncle. She had the misfortune to be plain looking, though her connections and wit were enough to win her a coveted place in the inner circle of Rideau Hall. The increasing popularity of society reporting, and the opening up of journalism to women, made it possible for her to earn a modest living through writing. Although not professionally ambitious, she supported most of the ideals of the independent “new woman” of the 1890s. “The best men in the land are the men who admire and help,” she wrote in 1898 of the newly founded National Council of Women of Canada, which she joined. “It is the man – you know him – who says, ‘I don’t let my wife do this’ and ‘I don’t let my wife do that!’ who is loud in his condemnation of the Council. Beware of him!”

Scott had begun reporting on Ottawa society as early as 1896, with an article for Lounger magazine (Ottawa) on a ball given by Lady Aberdeen [Marjoribanks*]. When she formally embarked on a career in journalism, she wrote pseudonymously, in the convention of the era. In Saturday Night, for which she prepared freelance columns until June 1902, she was Amaryllis. In the Ottawa Free Press, where she was on staff from December 1897 to February 1903, she wrote thrice-weekly as The Marchioness – a nom de plume borrowed, not from any haughty leader of society, but from the cheeky maidservant in Dickens’s novel The old curiosity shop, described there as “taking a limited view of society through the keyholes of doors.” Although she was also a correspondent for the Montreal Star, and did occasional pieces for Saturday Night on other topics, such as a trip to Paris in 1900, Ottawa was her stock-in-trade.

Some of her best columns poked fun at the rigid social protocols of the times. On 27 April 1897 she wrote in Saturday Night of the annual state drawing room held in the Senate Chamber and hosted by Governor General Lord Aberdeen [Hamilton-Gordon*]: “The ordeal of making two very low curtseys gracefully, rising without falling, getting out without turning your back on Her Majesty’s representative, is nothing compared to the criticism you know you are undergoing from your friends who have been previously presented and whom you pass as you advance to the throne. Such remarks as ‘No, it’s not a new gown, only done over,’ ‘I think she has had it dyed, but am not sure,’ ‘She ought to try to look more cheerful,’ are often heard.” Scott was not afraid of chiding the vice-regals. On the annual exhibition of the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts, at the National Gallery of Canada, she observed on 24 Feb. 1900 that it was in a building that also housed Canada’s fisheries exhibit. “Almost always, the Governor-General, in his speech on the opening night, alludes to the inadequacy of the place. . . . The Earl of Minto [Elliot*], who does not run to extreme originality in any particular, followed the example of his predecessors and advocated a new building.” At least Lady Minto did not “pull his sleeve . . . to offer a suggestion,” as Lady Aberdeen had been accustomed to doing when her husband spoke.

Scott hero-worshipped Laurier. In a charming piece on 21 Oct. 1899 she had described a chance encounter with the prime minister on an Ottawa streetcar. “Sir Wilfrid’s democratic principles will not allow of his riding in aught else but trams.” Far and away her most daring columns touched obliquely on his romantic relationship with the enigmatic Émilie Lavergne [Barthe], “a brilliant woman called by many the Canadian Lady Chesterfield.” (The real Lady Chesterfield had been a close friend of British prime minister Benjamin Disraeli, as Scott took for granted her readers would know.)

For six years she provided sparkling social reportage, seldom equalled in Canada. Although her columns provoked much comment and occasionally outrage, she was always invited back, a pattern which suggests that Ottawa in those days was a more sophisticated capital than is generally supposed. Her career ended abruptly in 1903 when she married Will Davis, a secretary some years her junior, son of a wealthy Ottawa contractor, and a playboy. Though their families had much in common – Irish, Catholic, and Liberal – there is much to suggest that their marriage was one of convenience. It was certainly unsuccessful. They built a fine house in Sandy Hill and had property in the Thousand Islands; Agnes entertained and found time to research and write papers for the Women’s Canadian Historical Society of Ottawa. But on Christmas Eve 1916 Will died suddenly in the apartment where, for years, he had been keeping a mistress.

Agnes stayed on in Ottawa, supported by her husband’s estate and the generosity of the Scotts and her father-in-law. Her loose handling of money evidently became an exceedingly sore point between the families. In 1926, by now in straitened financial circumstances, she and her daughters moved to France, where living was cheaper. Briefly, she reinvented herself as a writer, contributing a number of articles to the Montreal Star. She died in Paris of poliomyelitis in 1927.

ANQ-Q, CE301-S98, 14 févr. 1864. AO, RG 22-354, nos.8112, 13347; RG 80-5-0-310, no.5289. NA, RG 31, C1, 1901, Ottawa, St George’s Ward, div.5: 23 (mfm. at AO). Ottawa Evening Journal, 21 Nov. 1927. Ottawa Free Press, December 1897–February 1903. Sandra Gwyn, The private capital: ambition and love in the age of Macdonald and Laurier (Toronto, 1984). National Council of Women of Canada, Women of Canada: their life and work; compiled . . . for distribution at the Paris international exhibition, 1900 ([Montreal?, 1900]; repr. 1975), 76. Saturday Night (Toronto), March 1897–July 1902. Lilian Scott Desbarats, Recollections (Ottawa, 1957). “The Scotts of Tredinnock: some notes for the eleven grandchildren – some of whom remember their loving grandparents, the house and the gardens,” comp. Eileen Scott Morley (typescript, London, 1989; copy in the possession of Sandra Gwyn). Fraser Sutherland, The monthly epic: a history of Canadian magazines, 1789–1989 (Toronto, 1989).

Cite This Article

Sandra Gwyn, “SCOTT, AGNES MARY (Davis),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 21, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/scott_agnes_mary_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/scott_agnes_mary_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | Sandra Gwyn |

| Title of Article: | SCOTT, AGNES MARY (Davis) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2005 |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | February 21, 2026 |