Source: Link

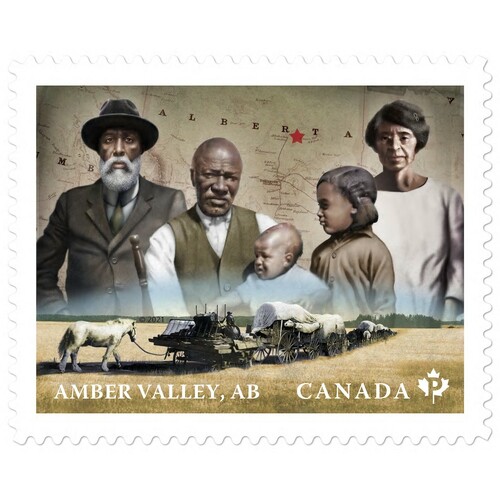

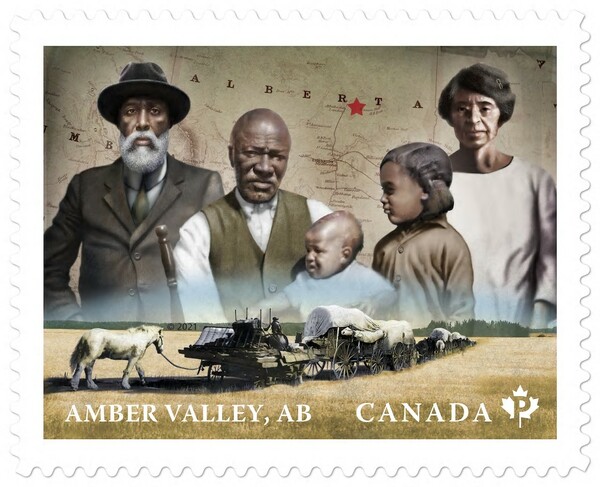

SNEED, HENRY, farmer and preacher; b. June 1848 in Texas; m. and had four sons, one of whom died young; m. secondly in the early 1900s Elizabeth Jefferson, a member of the Creek (Muscogee) Nation, and they had six children, one of whom died young; d. 18 July 1914 in Edmonton and was buried in what is now the Jordan W. Murphy Cemetery in Amber Valley, Alta.

Early life

Little is known about Henry Sneed’s early life. Census records indicate that his father was born in either Texas or Mississippi, the latter being the birthplace of Henry’s mother. He may have been enslaved while growing up in Texas. Henry lived for some time in Arkansas, where two of his sons were born. By 1898 he had moved to Indian Territory, which would later be joined with Oklahoma Territory to form the state of Oklahoma in 1907, where many Black people had travelled in the hope that the region would be a promised land. Although it is not known when his first wife died, records indicate that he was widowed and had remarried by the early 1900s. Sneed and his family settled in Clearview, one of the nearly 50 all-Black towns established in the territories. There he farmed and became a preacher (of what official standing and in which established faith is unknown).

The Last Best West

In the early 20th century many African Americans like Sneed decided that Oklahoma was not living up to the ideal they had envisioned. The state senate’s first bill introduced segregation in 1907. Facing increasing racial discrimination, some Black families, enticed by Ottawa’s promotion of its western provinces as the “Last Best West,” set their sights on the Canadian prairies. The campaign encouraged Americans to migrate, reassuringly noting the similarities between the American and Canadian west while highlighting that Canada had plenty of land that was good for wheat farming.

Articles and advertisements ran in papers throughout the United States, including those published by and sold in Black communities. One piece in the Boley Progress (6 Jan. 1910), a newspaper in the all-Black Oklahoma town 20 miles west of Clearview, noted the region’s similarities and reported that midwesterners “are pouring into the Canadian west in an ever-increasing stream, and are learning that ‘God Save the King’ and ‘My Country ’Tis of Thee,’ are sung to the same tune.” An April 1909 advertisement in the same paper went further, suggesting that the Canadian west was superior: “The 300,000 contented American settlers making their homes in Western Canada is the best evidence of the superiority of that country. They are becoming rich.”

It seemed that African American farmers would find acceptance in the Canadian west. On 15 April 1908, for example, the Edmonton Journal reported that a large number of them had arrived in the city and “the prospects are that they will make fairly good settlers.” Sneed travelled north in the summer of 1910 to scout possible homestead locations. He was probably accompanied by Nimrod Toles, a fellow resident of Clearview. While in Alberta, Toles took out a homestead; Sneed would do so the following year. Earlier in 1910 another African American Oklahoman, Jordan Washington Murphy, also purchased a homestead. Murphy may have travelled with Sneed and Toles, although the record is not clear. All three men would become leaders of their community. They soon discovered, however, that they were not welcome.

Dissuading African American immigration

Although Canada wanted thousands of American farmers to move north, it had no wish to include African Americans among them. In the absence of an official colour bar, the Department of the Interior had been employing other means to discourage their migration. As early as 23 Jan. 1899, Francis Pedley, superintendent of immigration under Clifford Sifton*, the department’s Liberal minister, had informed John Sanderson Crawford, the immigration agent in Kansas City, Mo., that “it is not desired that any negro immigrants should arrive in Western Canada.” After receiving a June 1903 request for information about whether the Department of the Interior would support African American migration to Canada, William Duncan Scott*, who, earlier in the year, had replaced Pedley as superintendent of immigration, replied that “the Canadian Land Regulations place no obstacles in the way of coloured men making homestead entries, but the Government of Canada is not especially desirous of encouraging this class of immigrant.” Immigration officials aimed to dissuade such migration by withholding promotional material, circulating information that Canadian weather was inhospitable to African Americans, and stating that the government believed they would not succeed as settlers in western Canada.

When the mp for Edmonton, Liberal Frank Oliver*, replaced Sifton as minister of the interior in 1905, he began to restrict immigration. Oliver’s initial legislative revisions strengthened the government’s ability to deny entry based on health or financial concerns. Further amendments to the Immigration Act in 1910 gave Ottawa new powers to exclude “any race deemed unsuited to the climate or requirements of Canada,” a policy intended in part to deny Black immigration.

Against this background, the arrival of Sneed, Toles, and Murphy in the spring and summer of 1910, along with increasing numbers of African Americans from the American west, was a source of alarm for many white Canadians and government officials. In Alberta, there were complaints about a perceived influx of Black migrants. Edmonton resident John K. Powell, a self-described Canadian who had lived for 14 years in the southern United States, wrote a lengthy letter to Oliver on 2 March 1910 about Black people moving to Alberta. Powell was “convinced” that Canada “would be better off without them” and cautioned the Edmonton mp that “the average Canadian does not seem aware that the darky may be vicious.” Even if all African American immigrants “were good,” Powell continued, it was still “unwise … to receive any of them, for the simple reason that they cannot be assimilated.” On 12 April the Edmonton Board of Trade passed a unanimous resolution, sent to both Oliver and Liberal prime minister Sir Wilfrid Laurier, that called for a halt to the migration lest it lead to a “Negro Problem” in western Canada. The backlash continued into 1911, when the Edmonton Board of Trade circulated a petition urging the exclusion of Black migrants from Canada. Within only a few weeks the petition had 3,500 signatures. The boards of trade in other Alberta communities, including Strathcona, Morinville, and Fort Saskatchewan, made similar complaints.

J. S. Crawford, Ottawa’s immigration agent in Kansas City, struggled to prevent African Americans from coming north. In late March he assessed the reasons for their migration in a letter to W. D. Scott: “These people were formerly Indian Slaves and have become mixed and now are owners of Indian lands as a result and well to do. Oklahoma has a Jim Crow Car law which is offensive to these people and the chief reason they want to get away. I think they are largely advised by their Preachers who have visited Canada and made arrangements for their move.”

From Emerson to Alberta

J. S. Crawford’s view that preachers were helping Black Oklahomans move to Canada was borne out by Henry Sneed’s role in his community. In their family histories, Sneed’s grandchildren mention that Henry promoted Alberta to freed Black people and others interested in migrating from Oklahoma. He also made sure that families were healthy enough to make the border crossing and that they had the financial resources to do so – both necessary under the 1910 Immigration Act, which required migrants to pass medical examinations and pay the requisite fee to border officials.

In March 1911 Henry Sneed and a party of approximately 20 families (comprising between 150 and 190 migrants), including members of his own family, left Oklahoma by train for Canada. Their progress was reported in Canadian and American newspapers, the wide interest stemming from rumours that Canada had begun prohibiting admission of Black Americans. On 21 March Frank Oliver’s Edmonton Bulletin claimed that “if any plausible excuse other than the color line can be found for detaining the party it will be done.”

A ban was not in place, but the day after Sneed’s party arrived at Emerson, Man., W. D. Scott sent a memo to Frank Oliver making the case for prohibition: “As regards the colour line, the Government have already drawn it insofar as the yellow races are concerned.… I fail to see wherein negroes are more desirable than the yellow races, and if some drastic action to prevent the threatened influx is not taken the Government is likely to receive … reprimand from portions of Alberta and Saskatchewan to which the negroes are proceeding.” Scott’s proposal aligned with the views of his immigration agents, including W. H. Rogers, Crawford’s replacement in Kansas City, who believed that “until prohibitive legislation is adopted, practically the only means we have to check this movement is through the Agency of fear rather than the force of opposition. The negro has a mortal dread of the graveyard, and we must show him that a sudden transition from a Southern to an almost Arctic latitude means disease and death.”

Over a two-day period the settlers whom Sneed had led north paid their immigration fees, passed medical examinations, and were allowed to cross the border. In total, the migrants brought seven trainloads of goods. Many of the families possessed at least $200; some may have had between $1,000 and $3,000. They then made their way towards the Pine Creek region, north of Edmonton. The day after they left Emerson, the Calgary Herald reported that Sneed, “the organizer” of the party, “was more than pleased at the result of the inspection.” On 25 March 1911 another article described Sneed as a “bearded patriarch” who was proudly defiant about the successful passage. He told a reporter, “There ain’t nothin’ the matter with us, mister. Sick! Ah’d like youh to show me whar we got any sick peoples. We are going to take up our homesteads near Athabasca Landing as soon as our effects arrive. We have all of our implements and horses and wagons and we’re goin’ in for farmin’ straight. All of our men have farmed all their lives.” The Herald further credited Sneed, referred to as Daddy Snaid, with having “spied out the land up here last summer for this colony” and deemed him “a wise scout,” claiming that “it was mostly due to his wiles that the party safely crossed the border.”

Outcomes

Although the number of Black immigrants to Canada totalled only about 1,000 by the spring of 1911, many white settlers in Alberta, like members of the Canadian government, evidently feared that thousands more would soon follow. On 2 June, Frank Oliver acted on W. D. Scott’s advice to ban African American immigration. Oliver submitted to cabinet a proposal prohibiting “any immigrants belonging to the Negro race, which race is deemed unsuitable to the climate and requirements of Canada from landing in Canada for one year.” Perhaps under pressure to retain the Liberals’ popular support in western Canada during an election year, Laurier signed the order in council excluding Black migrants on 12 August. The move was a political gamble that risked alienating voters in eastern Canada. As it transpired, Laurier lost the 1911 election to Robert Laird Borden*’s Conservative party.

Laurier cancelled the ban on Black immigration in the final days of his administration (there remains some question about whether the ban had ever been implemented). For African Americans looking to come to Canada, however, the damage was already done. Sneed’s party represented one of the last large migrations of families from Oklahoma. The Department of the Interior’s position was clear: whether or not Black people could legally migrate, they were not welcome. Yet Sneed helped Black immigrants find success in Amber Valley. (One of his descendants, Floyd Sneed, was the drummer for the musical group Three Dog Night.) Henry Sneed died in 1914, only a few years after leading his party north. The community he helped to found prospered for decades and fostered a vibrant Black Canadian culture in Alberta.

Some sources relevant to this biography have been incorrectly cited in the literature about Black immigration to Alberta. The following, held at Library and Arch. Can. (Ottawa), are accurately referenced here: William Duncan Scott’s memorandum to Frank Oliver proposing an order in council to prohibit the admission of Blacks in Canada is in RG76-I-A-1, vol.193, file 72552, pt.4 (Dept. of Employment and Immigration fonds, Immigration sous-fonds, …, immigration of Negroes from the United States to western Canada). Oliver’s proposal can be found in the same file. The order in council prohibiting Black immigration is no.1911-1324; the order rescinding the ban is no.1911-2378.

Ancestry.com, “1900 United States federal census,” Henry Sneed, Indian Territory, Creek Nation, Township 11; “1910 United States federal census,” Henry Sneed, Okla., Okfuskee, Lincoln; “Alberta, Canada, homestead records, 1870–1930,” Henry Sneed, Jordan Washington Murphy; “Canada, border crossings from U.S. to Canada, 1908–1935,” H. Sneed, Emmerson, Man., 23 March 1911; “Oklahoma and Indian Territory, U.S., Indian censuses and rolls, 1851–1959,” Kizzie [Lizzie] Jefferson; “U.S., Native American enrollment cards for the Five Civilized Tribes, 1898–1914,” Lizzie Jefferson. Find a Grave, “Jordan W. Murphy,” memorial no.36001586; “Henry Sneed,” memorial no.35997183; “Nimrod Toles,” memorial no.36002677. Library and Arch. Can., “Census of Canada, 1911,” Sneed Henery [Henry], Alberta, Victoria, 8; RG76-I-A-1, vol.192, file 72552, pt.1 (Dept. of Employment and Immigration fonds, Immigration sous-fonds, …, immigration of Negroes from the United States to western Canada) (link, images 1553, 1565, 1710, 1728, 1746); RG76-I-A-1, vol.193, file 72552, pt.3 (Dept. of Employment and Immigration fonds, Immigration sous-fonds, …, immigration of Negroes from the United States to western Canada) (link, images 259–601). National Arch. (Fort Worth, Tex.), RG75 (Records of the Bureau of Indian Affairs), Enrollment cards, Dawes enrollment cards for Creek, freedmen (F), 1800–1917, Julius Sneed; (Kansas City, Mo.), Applications for enrollment in the Five Civilized Tribes (Kansas City, Mo. branch), Elvida and Mathew Sneed. PAA, death records, Henry Sneed, Edmonton, 18 July 1914 (no.2229.R). Boley Progress (Boley, Indian Territory [Okla.]), 16 March 1906; 8 April 1909; 24 March, 22 Dec. 1910. Calgary Herald, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 27, 28 March, 15 April 1911; 16 Aug. 1974. Edmonton Bull. 22, 23, 25 March, 5 June 1911. Edmonton Capital, 25 March, 30 May 1911. Globe and Mail (Toronto), 23 Feb. 2023. Okemah Ledger (Okemah, Indian Territory [Okla.]), 30 March 1911. Oklahoma Guide (Guthrie, Okla.), 20 April 1911. Warren Sheaf (Warren, Minn.), 23 March 1911. Winnipeg Free Press, 23, 27, 28 March, 24, 30 May 1911. Winnipeg Tribune, 22 March 1911. East Athabasca Hist. Book Soc., Land of dreams: districts east of Athabasca: Golden Sunset (Tawatinaw), Parkhurst, Toles (Amber Valley), Rodger’s Chapter, Forest, Ferguson, Clover View (Athabasca, Alta., 2009). Dianna Everett, “Land openings,” in Okla. Hist. Soc., The encyclopedia of Oklahoma history and culture. Forests, furrows, and faith: a history of Boyle and districts, comp. Boyle and District Hist. Soc. (Boyle, Alta., 1982). J. S. Hill, “Alberta’s Black settlers: a study of Canadian immigration policy and practice” (ma thesis, Univ. of Alta, Edmonton, 1981). Valerie Knowles, Strangers at our gates: Canadian immigration and immigration policy, 1540–2006 (rev. ed., Toronto, 2007). S.-J. Mathieu, North of the color line: migration and black resistance in Canada, 1870–1955 (Chapel Hill, N.C., 2010). Larry O’Dell, “Clearview,” in The encyclopedia of Oklahoma history and culture. Frank Oliver, Minister of the Interior, The last best west … (Ottawa, [1906]). Robert Rogers, Minister of the Interior, Canada west: the last best west (Ottawa, 1911). R. B. Shepard, Deemed unsuitable: blacks from Oklahoma move to the Canadian prairies in search of equality in the early 20th century only to find racism in their new home (Toronto, 1997). H. M. Troper, Only farmers need apply: official Canadian government encouragement of immigration from the United States, 1896–1911 (Toronto, 1972). U.S. Senate, Senate documents (Washington), 1909–10, no. 469 (report of the immigration commission, “The immigration situation in Canada,” 1910). Rachel Wolters, “‘We heard Canada was a free country’: African American migration in the Great Plains, 1890–1911” (phd thesis, Southern Ill. Univ., Carbondale, 2017).

Cite This Article

Rachel Wolters, “SNEED, HENRY,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 25, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/sneed_henry_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/sneed_henry_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | Rachel Wolters |

| Title of Article: | SNEED, HENRY |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2026 |

| Year of revision: | 2026 |

| Access Date: | February 25, 2026 |