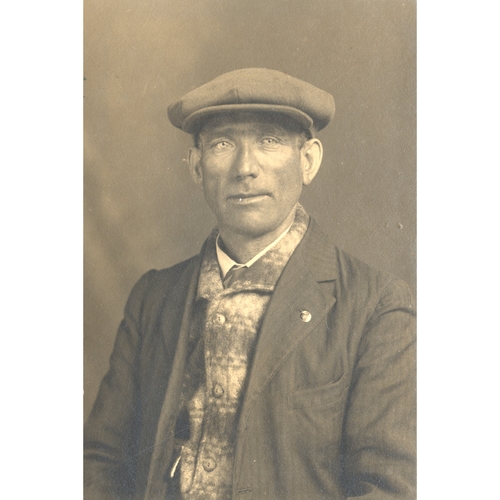

![George Tuff, Second Hand of the SS Newfoundland, n.d. [Photographer S. H. Parsons and Sons]. Reproduced by permission of Archives and Special Collections (Coll. 115 16.04.032), Memorial University Libraries, St. John's, Newfoundland and Labrador. Original title: George Tuff, Second Hand of the SS Newfoundland, n.d. [Photographer S. H. Parsons and Sons]. Reproduced by permission of Archives and Special Collections (Coll. 115 16.04.032), Memorial University Libraries, St. John's, Newfoundland and Labrador.](/bioimages/w600.11373.jpg)

Source: Link

TUFF, GEORGE, fisherman and sealer; b. 7 May 1881 in Bennett’s Island (Wesleyville), Nfld, son of William Tuff and Selina Parsons; m. probably c. 1902 Julia Sophia Melendy at Templeman (Wesleyville), Nfld, and they had five children; d. there 21 Aug. 1937.

George Tuff came from a fishing family of the northeast coast of Newfoundland. As a boy he learned the trade in small boats inshore, and further out on the schooners that travelled to Labrador. While fishing occupied much of his year, it was Tuff’s work in the spring seal hunt that earned him public attention later in his life. The hunt was economically and culturally vital to communities such as his, but it was a dangerous industry. Every year men journeyed deep into the ice offshore on wooden-hulled steamers or, less frequently, on iron-hulled vessels. Sealing captains dropped crew members, organized into four groups called watches, over the side to kill seals. Sudden storms, shifting ice, poorly equipped ships, exhaustion, and injury were constant threats, but men nevertheless clamoured to go. Their families needed the income, and captains with reputations for canniness in finding seals were widely admired. Many northeast-coast sealers, Tuff among them, were Methodists who embraced a fatalistic belief that the bitter hardships of the hunt were providential tests of their dutiful characters. For younger men, participation signified that they were able to meet their masculine obligations to their households and communities.

Tuff was only 16 when he first went sealing in 1897. The next year he joined the Greenland, which was under the command of Captain George Barbour. On 20 March Barbour put his men over the side, but bad weather prevented him from returning to pick up three of the four watches on the ice and the stranded men spent the night in a furious blizzard. Although Tuff survived, 48 of his shipmates died.

There was a public outcry against working conditions in the seal hunt, but little changed to prevent future tragedies. Tuff was at the centre of one of the most infamous: the Newfoundland disaster of 1914. He rose quickly in the ranks of the industry after 1898, earning the confidence of Abram Kean*, the most senior and celebrated of the sealing captains in 1914. By then Tuff had ten years’ experience as master of a watch, the last three on the Newfoundland under Westbury Bethel Bullen Kean, one of Abram’s sons, and that spring Tuff was his second hand, the officer responsible for the ship’s operations. Wes Kean could not find seals, but on 30 March the after derrick was raised on his father’s ship, the Stephano, to signal that a herd had been located. The younger Kean decided to send out about 160 men over the ice the next morning and Tuff volunteered to lead them, making light of the risks of the weather and the walk, a distance of some five to seven miles. In their testimony at a public inquiry that would be held a few weeks later, the two men gave conflicting accounts of what happened next: Wes Kean recalled telling Tuff to spend the night on the Stephano, but Tuff believed that his orders were to simply walk to the Stephano and follow the instructions of Abram Kean.

Daunted by the worsening weather, about 30 of the Newfoundland’s crew turned back, facing catcalls of cowardice by their mates who pressed on and the epithets of their captain, who derided them as “grandmothers.” Those who arrived at the Stephano had struggled over the ice for more than four hours, but they were given only a short rest and a meal by Abram Kean before he dropped them off at a patch of seals. Although the tired men wanted to call off the hunt and retreat to the Stephano, Tuff did not question Abram Kean’s orders that they return to their own ship. As the storm grew Tuff tried to take everyone back to the Newfoundland, but they soon became lost. Both Keans thought that the sealers were safe aboard each other’s ship, and the two captains had no way to contact each other because the Newfoundland’s owners, A. J. Harvey and Company, had removed the wireless radio to cut costs.

The result was tragedy. The men wandered through snow and freezing rain for at least 53 hours until they were rescued by the Bellaventure, the Florizel, and the Stephano. Most were improperly clothed and had little food. Fathers and sons, brothers and uncles, and best friends from childhood tried to keep each other going, but many succumbed. The tragedy was all the worse because the Bellaventure and Stephano had steamed close to the lost crew, but they had not been seen; moreover, on the second day Tuff had brought a small group to within two miles of the Newfoundland before the ship broke free of the ice and steamed away from them. Reports vary, but at least 78 of the crew perished.

The majority report of the three-man public inquiry headed by Sir William Henry Horwood* blamed Abram Kean for failing to properly care for the men of the Newfoundland. So did William Ford Coaker, president of the Fishermen’s Protective Union of Newfoundland, who thundered in a speech to the FPU that Kean “could have saved all the men had he taken proper steps and been guided by ordinary discretion and the dictates of common sense.” Kean, however, denied responsibility. The majority report faulted Tuff for not insisting that the men be allowed to stay on the Stephano, a criticism which he accepted, though he maintained that he had been ordered by Wes Kean to follow Abram Kean’s instructions. Tuff’s leadership was also questioned because he had ordered the master of one watch to lead the walk back to the Newfoundland so that Tuff, regardless of his own safety, could stay behind to help stragglers. Some survivors thought that Tuff should have led the way himself, but the inquiry’s minority report absolved him of any guilt, stating that “throughout the ordeal he played the man.” His manliness lay not only in his courage and hardiness, but also in his obedience to the sealing captains. Respectable and trusted crew members did not defy the captains, especially such a well-respected and paternalistic figure as Abram Kean.

George Tuff remained friendly with Westbury Kean, although he was less so with Abram Kean. He gave up the hunt after a few more years. Active as a lay reader in his church and as a Sunday-school superintendent, Tuff died at the relatively young age of 56, worn out, his son Jabez felt, by the tragedies he had endured on the ice off the coast of Newfoundland.

George Tuff’s dates of birth and death are confirmed by his baptismal record in RPA, Methodist parish records, Greenspond, Reg. of baptisms, Box 2, 1876–1886, and his death certificate (Nfld, Dept. of Service NL, Govt. services branch, Vital statistics div. (St John’s), no.FD46986). His ordeal in 1914 was later recounted by his son Jabez and the story is available at Folklore and Language Arch., Memorial Univ. of Nfld (St John’s), Cassette 86-149/C10086 (Shannon Ryan, interview with Jabez Tuff, 31 July 1986). Tuff’s testimony before the public inquiry of 1914, and related documents, can be found in the Cassie Brown coll. (Coll-115, file 9.01.018), Arch. and Special Coll., Queen Elizabeth II Library, Memorial Univ. of Nfld. Abram Kean gave his own version of the events in his 1935 book Old and young ahead … (London), later reissued with an introduction by editor Shannon Ryan (St John’s, 2000). See also Nfld, Commission of enquiry into the sealing disasters of 1914, Report (St John’s, [1915], which is available online at collections.mun.ca/cdm/ref/collection/cns/id/75876), and Cassie Brown, with Harold Horwood, Death on the ice: the great “Newfoundland” sealing disaster of 1914 (Toronto, 1972). The single best history of the seal hunt is Ryan’s indispensable The ice hunters: a history of Newfoundland sealing to 1914 (St John’s, 1994). Also useful are J. E. Candow, Of men and seals: a history of the Newfoundland seal hunt (Ottawa, 1989); John Feltham, Sealing steamers (St John’s, 1995); and S. T. Cadigan, Newfoundland and Labrador: a history (Toronto, 2009). Sandra Beardsall offers important insight into why sealers may have tolerated their treatment in the hunt in “Methodist religious practices in outport Newfoundland” (thd, Emmanuel College, Victoria Univ., Toronto, 1996).

Cite This Article

Sean T. Cadigan, “TUFF, GEORGE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 31, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/tuff_george_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/tuff_george_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Sean T. Cadigan |

| Title of Article: | TUFF, GEORGE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2018 |

| Year of revision: | 2018 |

| Access Date: | December 31, 2025 |