VANDERPANT, JOHN (named at birth Jan van der Pant), author, photographer, and lecturer; b. 11 Jan. 1884 in Alkmaar, Netherlands, eldest child of Jan van der Pant and Catharina Sophia Ezerman; m. 6 July 1911 Catharina Johanna over de Linden (d. 1955) in Haarlem, Netherlands, and they had a son, who died in infancy, and two daughters; d. 24 July 1939 in Vancouver.

Jan van der Pant would change the spelling of his name sometime between 1914 and 1919, but would use the original presentation in articles he published in the Netherlands in the 1920s. He grew up in Alkmaar, the son of a tobacconist and importer of moderate income. He was heir to the family business and entered it briefly, but his calling lay elsewhere. While enrolled in the faculty of literature at Leiden University from 1905 to 1912, he began to write poetry and he would continue to do so throughout his life; he published poems in Dutch literary magazines between 1907 and 1910 and a book entitled Verzen [Verses] (Haarlem) in 1908. In January 1908 his first photograph, a winter scene, was reproduced in Nederland in rijp … [The Netherlands covered in hoar frost] (Koog-Zaandijk [Zaanstad]). He also developed lifelong interests in music, the history of languages, and spiritual philosophies; he would later become intrigued by Christian Science and theosophy.

In 1910, while still a university student, Vanderpant began working as a photojournalist for the magazine Op de Hoogte [Well Informed] (Amsterdam) although he had no formal training as a photographer. From 1910 to 1914 he published illustrated articles on countries such as the Netherlands, Italy, Portugal, and Canada. Beguiled by the beauty of the Canadian landscape and interested in the opportunities available in the New World, he and his wife immigrated in 1911. Over the next two years his articles and photographs illustrating the advantages in Canada for Dutch farmers appeared in magazines and newspapers in his native land. In 1912 he worked briefly for the Canadian government, lecturing in the Netherlands on the benefits of immigration.

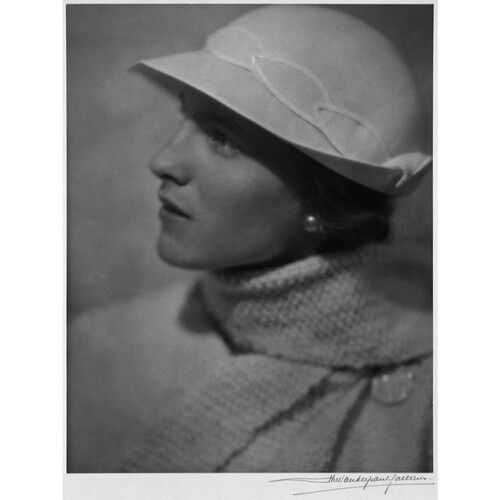

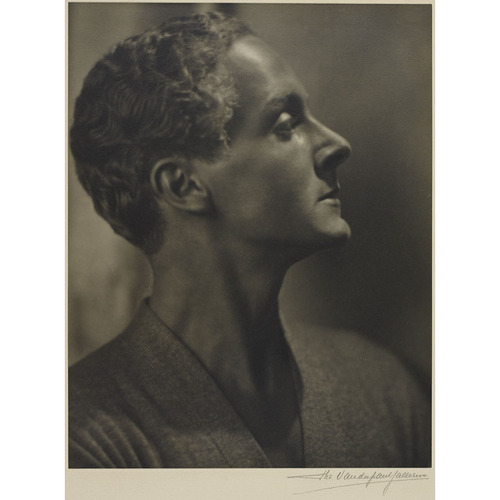

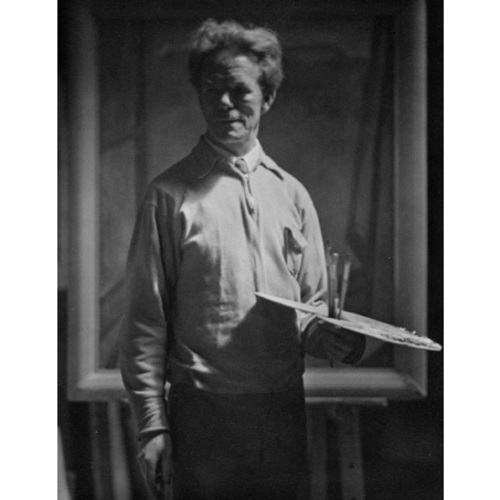

Vanderpant opened his first commercial photographic studio in 1912 in the small town of Okotoks, Alta. Soon after, he established two other studios: in Fort Macleod and Pincher Creek. Although his businesses were thriving, he and his wife struggled with the deprivations of life in Okotoks. In 1919 they moved to New Westminster, B.C., where Vanderpant opened the Columbia Studio. Word of his talent spread and during the interwar years his portrait work was among the best in Canada. Using intriguing poses and innovative lighting, Vanderpant conveyed the intrinsic characteristics of his clients, creating what he termed “living” prints. One of his most famous portraits, taken in 1929, is of Indian writer and philosopher Rabindranath Tagore. Other renowned sitters included author Bertram Richard Brooker*, poet William Bliss Carman*, pianist and composer Jean Coulthard*, artists Alexander Young Jackson* and Frederick Horsman Varley*, and the Hart House String Quartet.

In 1921 Vanderpant had met photographer Harry Upperton Knight*, whose pictorial style inspired him to strive for a painterly effect. He began to photograph landscapes and ordinary objects and entered his black and white prints in local exhibitions and international salons. Using a silver-bromide printing process, toned matte papers, and an Ansco camera with an f/6.3 anastigmatic lens, he achieved a soft-focus evocativeness. His work met with success; it was reproduced in numerous European and American journals. His photographs were the only ones from Canada shown in the exhibition of the Royal Photographic Society of Great Britain in 1922. Two years later an art museum in San Francisco purchased his print The window’s pattern for its permanent collection. The following year Vanderpant had a solo exhibition at the Hotel Vancouver and another sponsored by the Royal Photographic Society in London. He was made a fellow of the society in 1926. His studies won him so much recognition between 1922 and 1926 that he would later claim he could weigh his medals “by the pound … [and] paper a wall with his certificates.” From 1925 to 1934 one-man exhibitions of his work toured Canada, the United States, and Europe. In 1934 he was the first Vancouver artist to have an individual showing at the Seattle Art Museum. The Vancouver Art Gallery held displays of his prints in 1932 and 1937 and a retrospective in 1940. In 1976 the National Gallery of Canada would sponsor an exhibition of his work that travelled across the country.

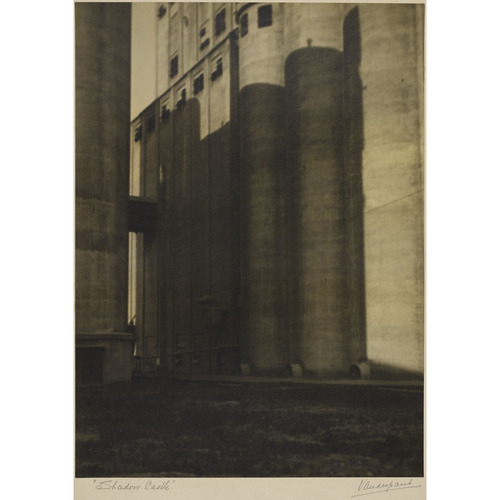

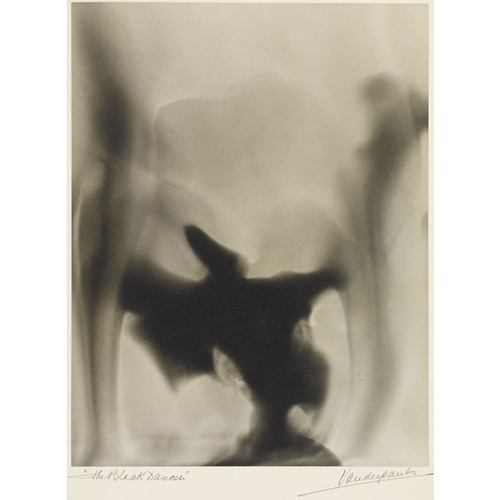

Vanderpant stated that his main influences were the works of American photographers Alvin Langdon Coburn, Edward Steichen, and Clarence Hudson White. He developed a unique and often spiritually motivated style which incorporated out-of-context close-ups, unusual angles, soft tones, and dramatic lighting to convey the sensual beauty of everyday objects. He would often crop, dodge, enlarge, or retouch an image to convey his “ideas in light.” Although he never totally rejected pictorialism, he may have started his move to increasingly abstract studies of natural and commonplace objects as early as 1926. Close-ups of flowers, fruits, vegetables, and linen shirt collars, combined with his “play of light and shadow,” are among his most successful studies. Criticism in 1925 from an unknown reviewer that his work did not reflect the Canadian “spirit” had led him to turn his camera to the west coast’s concrete grain elevators. According to curator Rosemary Donegan, those distinctive prints are now recognized as “symbolic images of Canadian industrial architecture.”

Like Coburn, Steichen, and White, Vanderpant advocated having photography accepted as an art. In 1920 he had inaugurated the first New Westminster Photographic Salon; three years later he launched the New Westminster International Salon of Pictorial Photography, held yearly until 1929. This new salon, along with Vancouver’s first International Master Salon of Pictorial Photography, which Vanderpant held in 1927, were the only international salons in the west during the 1920s. Between 1919 and 1930 there were only two other international salons in Canada, in Toronto and Ottawa. Since 1923 Vanderpant had been publishing articles on photography in foreign publications; in 1924 he began lecturing to local, national, and international camera clubs, photographic associations, and art groups. He spoke about (and often defended) progressive movements in architecture, music, painting, photography, and poetry. He believed that the artist was a “channel” or “interpreter,” helping “the masses” to understand that “art is the consciousness of life expressed in aesthetic form, pattern, rhythm, and color relationship … [it is] the echo of the absolute.” His comments were vital to Canada’s amateur photographers since communication between them was difficult (not until the late 1960s would there be a national photographic journal). In 1935, under the auspices of the National Gallery, Vanderpant travelled across Canada lecturing on photography; two years later the University of Alberta sponsored his talks in Edmonton, Calgary, and Lethbridge.

Vanderpant influenced numerous Canadian photographers, including Johan Anton Joseph Helders*, who is described by archivist Joan Marsha Schwartz as “Canada’s outstanding amateur pictorialist” during the 1920s and 1930s. Furthermore, according to art historian Melissa K. Rombout, Vanderpant may also have kindled renowned portraitist Yousuf Karsh*’s interest in art photography during the 1930s, since negatives by Karsh “suggest an awareness of and an interest in the dramatic, abstracted architectural views of Vanderpant.”

In 1926, with journalist and art critic Harold Mortimer Lamb*, Vanderpant had opened the Vanderpant Galleries (with a photography studio) at 1216 Robson Street, Vancouver. The partnership dissolved after a year because of financial and artistic disagreements, but Vanderpant persevered alone and the galleries became a focal point in the city for new and modern examples of photography, painting, music, and poetry. Works by a number of Canada’s then up-and-coming, and often controversial, artists regularly hung on the walls. In 1931 Vanderpant held two significant exhibitions there. Canvases by Emily Carr*, Max Singleton Maynard*, Charles Hepburn Scott, William Percy Weston, members of the Group of Seven, and others were displayed in April. In September Vanderpant presented the work of two American photographers; it was the first Canadian showing for Imogen Cunningham and the second for Edward Weston.

From 1928 to 1936 Vanderpant hosted evenings of recorded music on his Columbia gramophone. Vancouver did not yet have a symphony orchestra and those attending the soirées thrilled to the music of the “old masters” as well as to recordings of modern compositions which Vanderpant imported from Europe and the United States. The British Columbia Art League, Vancouver’s Arts and Letters Club, and the Vancouver Poetry Society (Vanderpant was a member of all three) regularly met at the galleries, as did students from the Vancouver School of Decorative and Applied Arts. Artists such as Varley and James Williamson Galloway (Jock) Macdonald* were frequent visitors to his home.

In 1930 Vanderpant won a prestigious commission to capture “the spirit and progress of the railroad” for the Canadian Pacific Railway’s jubilee of 1931. Chosen because he had “imagination and can get much out of little,” he spent six weeks travelling from British Columbia to Quebec and shot approximately 1,000 photographs. Unfortunately, the prints are not identified in the CPR’s archives.

The Great Depression exacted a toll on Vanderpant’s finances and in 1934 he and his family were obliged to sell the home they had built in Vancouver only four years earlier. They took up residence in the cramped quarters above the Robson Street galleries. By 1937 artist friends such as Varley and Philip Henry Surrey* had moved from Vancouver. Vanderpant’s loneliness and a growing sense of artistic solitude were compounded by his failing health; lung cancer caused his artistic output to decline and his daughters took over the business. He died at home, sustained by his family and his spiritual beliefs.

A vivacious, innovative man with a wry sense of humour, John Vanderpant was a significant force in Canadian photography during the 1920s and 1930s. Through his various endeavours he became a catalyst in Vancouver’s isolated fine-arts community. His dramatic compositions and his efforts to champion Canadian art are a vital part of the nation’s photographic and cultural history.

LAC, R2991-0-3. Private arch., Sheryl Salloum (Vancouver), Corr. between Sheryl Salloum and Melissa K. Rombout, 1993. Norman Hacking, “Cabbages and cameras,” Vancouver Province, 30 Nov. 1935. A. J. Birrell et al., Private realms of light: amateur photography in Canada/1839–1940, ed. Lilly Koltun ([Ottawa], 1984). A. F. Currie, “The Vanderpant musicales,” Paint box (Vancouver), 1928: 48. Rosemary Donegan, Industrial images (exhibition catalogue, Art Gallery of Hamilton, Ont., 1988). J. [A. J.] Helders, “How I make my exhibition prints: methods and ideals of well-known pictorial workers,” Amateur Photographer & Cinematographer (London), 21 Oct. 1931: 385. C. C. Hill, John Vanderpant: photographs (exhibition catalogue, National Gallery of Can., Ottawa, 1976). Sheryl Salloum, “Fine grain,” Vancouver, June 1990: 48–51; “John Vanderpant and the cultural life of Vancouver, 1920–1939,” BC Studies (Vancouver), no.97 (spring 1993): 38–50; “John Vanderpant’s vibrating ‘voice’ and vision,” Photographic Canadiana (Toronto), 25 (1999–2000), no.2: 8–11; Underlying vibrations: the photography and life of John Vanderpant (Victoria, 1995).

Cite This Article

Sheryl Salloum, “VANDERPANT, JOHN (Jan van der Pant),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 9, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/vanderpant_john_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/vanderpant_john_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Sheryl Salloum |

| Title of Article: | VANDERPANT, JOHN (Jan van der Pant) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2014 |

| Year of revision: | 2014 |

| Access Date: | March 9, 2026 |