Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

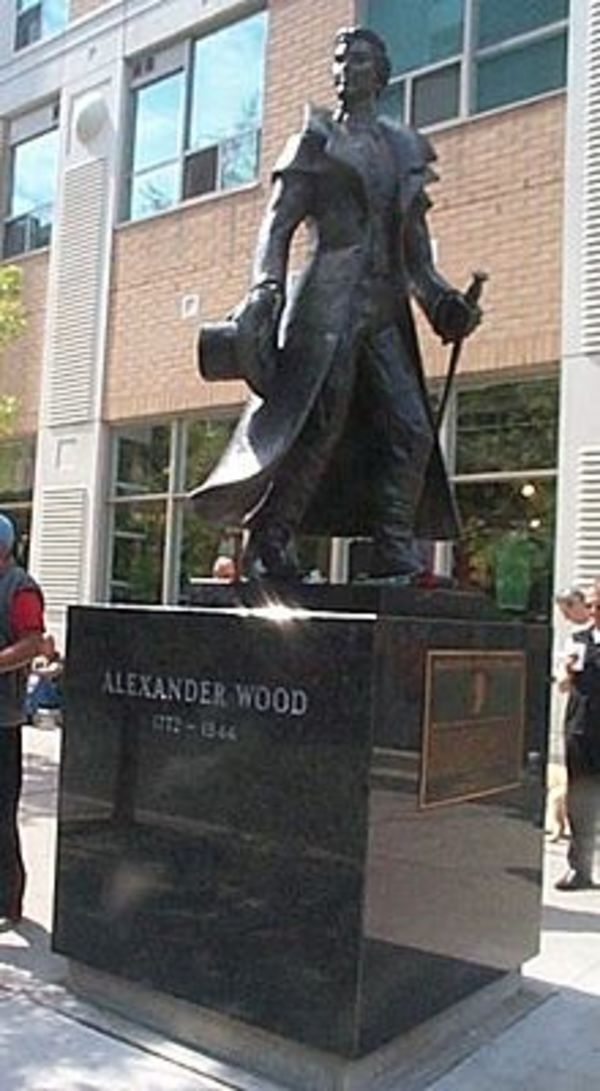

WOOD, ALEXANDER, businessman, militia officer, jp, and office holder; b. 1772 and baptized 25 January in Fetteresso, near Stonehaven, Scotland, son of James Wood and Margaret Barclay; d. unmarried 11 Sept. 1844 at Woodcot in the parish of Fetteresso.

Alexander Wood came to Upper Canada as a young man, settling in Kingston about 1793 and investing £330 in the Kingston Brewery in partnership with Joseph Forsyth* and Alexander Aitken*. He moved to York (Toronto) in 1797 to establish himself as a merchant. He and William Allan* became partners; “neither advanced any money which brought us on a fair footing,” but they built their shop on Allan’s land. When the partnership was dissolved on 13 April 1801 its assets were divided with difficulty, so that neither partner wanted to renew their intercourse “by the exchange of a single word.”

Wood immediately opened his own shop. Each autumn he ordered a wide assortment of goods from Glasgow or London, stressing quality and careful packing rather than price. Almost all his stock came from Britain except tea and tobacco, which, before the American Embargo Act was extended to inland waters in 1808, he bought in the United States through Robert Nichol*; small, immediate requirements were ordered from Montreal or New York. Wood was fortunate because his elder brother in Scotland, James, made up any deficit owing in Britain until full payment could be sent from Upper Canada. His customers included Lieutenant Governor Francis Gore*, a fair proportion of York’s carriage trade, army officers, and the commissariat – none of whom paid as promptly as Wood wished. He also dealt with neighbourhood farmers, supplying their needs and exporting their flour. Fluctuations in the quantity and price of flour were frequent, but Wood prospered in this business. He was not so successful with potash or hemp, and made only one ill-fated sortie into the fur trade.

With William Allan and Laurent Quetton* St George, Wood was one of the leading merchants in York before the War of 1812. When he first arrived, it was little more than a clearing in the bush, far inferior to Kingston and the towns of the Niagara peninsula in commercial development, but it grew rapidly, stimulated by government money and the settlement of its hinterland. Wood belonged to the group of “scotch Pedlars” whose influence judge Robert Thorpe so much deplored. “There is a chain of them linked from Halifax to Quebec, Montreal, Kingston, York, Niagara & so on to Detroit,” he wrote in 1806. Wood carried on a regular correspondence with James Irvine* (Quebec), James Dunlop* and James Leslie* (Montreal), Joseph Forsyth (Kingston), Robert Hamilton* and Thomas Clark* (Niagara peninsula), Robert Nichol (Fort Erie and Dover (Port Dover)), and other Scottish merchants, who gave and received assistance, and exchanged commercial and local news.

Wood was one of the few merchants accepted among York’s élite. His closest friends were William Dummer Powell* and his family, with whom he was “a constant guest,” and George Crookshank* and his family. A warm friendship was developing by correspondence with the Reverend John Strachan* in Cornwall. “Our sentiments agree almost upon everything,” Strachan wrote in 1807. Wood was gazetted lieutenant in the York militia in 1798, appointed magistrate in 1800, and by 1805 was a commissioner for the Court of Requests, as well as being involved in every movement for community betterment or social enjoyment. His only problem was his health: he suffered, according to Dr Alexander Thom in 1806, from “a fullness of the Vessels of the Brain.” Anne Powell [Murray] wrote that “his complaint . . . tho’ not dangerous to his life is I fear to his intellects,” and the Powells got medical advice for him in both New York and London.

In June 1810 Wood’s world fell apart. Rumours spread throughout York that as a magistrate he had interviewed several young men individually, telling them that a Miss Bailey had accused them of rape. According to Wood, she had scratched her assailant’s genitals; each of the accused, to prove his innocence, submitted to Wood’s intimate physical examination. John Beverley Robinson* called Wood the “Inspector General of private Accounts . . . by which [name] he was occasionally insulted in the streets.” St George’s clerk reported that although Wood had received his shipment of British goods “no one goes near his shop.” Judge Powell asked his friend about the story, and was horrified when Wood admitted its truth: “I have laid myself open to ridicule & malevolence, which I know not how to meet; that the thing will be made the subject of mirth and a handle to my enemies for a sneer I have every reason to expect.” Powell replied that Wood’s offence was more serious: his abuse of his position as magistrate made him liable to fine and imprisonment. The evidence was submitted to the public prosecutor, “but from its odious nature, investigation was smothered” on the understanding that Wood leave Upper Canada. On 17 Oct. 1810 he departed for Scotland, leaving his clerk in charge of his shop.

Despite the scandal, Wood returned to York on 25 Aug. 1812, just after the outbreak of war, and resumed all his previous occupations, including that of magistrate. He had lost the Powells’ friendship, but the Crookshanks remained staunch friends and Strachan was now living in York – “Mr Wood commonly spends a couple of evenings and dines once with us during the Week,” he wrote in 1816. As a merchant Wood struggled fairly successfully with the problems of wartime transportation and supply, but his commercial position is shown in the York garrison accounts, in which his sales are a poor third to those of St George and Allan. By 1815 he had virtually retired, although his shop was not formally closed until 1821.

In 1817 Wood inherited his family’s estates and moved to Scotland, but in 1821 he returned to Upper Canada to settle his affairs. He would remain in York for 21 years, more involved with other people’s concerns than his own. Since his first arrival in York, he had acted as an agent for absentee landowners and others with business in the capital, among them D’Arcy Boulton* Sr, James Macaulay*, Lord Selkirk [Douglas*], George Okill Stuart*, and the widow of Chief Justice John Elmsley*. Wood himself neither invested nor speculated in land, but he spent much time on land transactions and property management for friends and clients. Throughout his life in Upper Canada he was active as a director or executive member in many organizations, among them the Bank of Upper Canada, the Home District Agricultural Society, the St Andrew’s Society, and the Toronto Library, and as the hard-working treasurer or secretary of others, including the Home District Savings Bank, the Loyal and Patriotic Society of Upper Canada, and the Society for the Relief of the Orphan, Widow, and Fatherless.

Wood’s public service involved membership on several government commissions. In 1808, when he was appointed to the second Heir and Devisee Commission, he was the only commissioner who was neither an executive councillor nor a judge of the Court of King’s Bench. Probably because of his frequent service as foreman of the Home District grand jury, he was appointed to commissions concerning the building of jails (1838) and a lunatic asylum (1839). He was a member of the special commission appointed in 1837 to examine persons arrested for high treason during the rebellion. On Strachan’s recommendation he was appointed to the commission to investigate war claims in 1823, but Chief Justice Powell refused on moral grounds to swear him in. Wood promptly sued Powell for damages, and the whole story of the 1810 scandal was retold. Although Wood won £120 damages with costs, Powell refused to pay, and in 1831 he published a pamphlet about the case. After Powell’s death, Wood visited his widow and forgave the debt. Mrs Powell, who usually reacted vehemently against anyone who had ever opposed her husband, wrote, “This liberal conduct reflects credit on our once zealous and sincere Friend.”

In 1842 Wood visited Scotland intending to return to Upper Canada, but he died there intestate in 1844. All his brothers and sisters had predeceased him, unmarried, including Thomas, who had come to York from Jamaica before 1810 and died in 1818. Because Canadian and Scottish laws of intestacy differed, it was necessary to establish Wood’s place of residence. The case reached the Court of Session (Scotland’s supreme court) in 1846 and the House of Lords two years later. In 1851 it was finally decided that Wood, despite his more than 45 years in Canada, had been a resident of Scotland, and by Scottish law his large estate passed to a first cousin once removed, “of whose existence he was most likely ignorant.”

Alexander Wood had come to Upper Canada with a good education, some capital, and the financial backing of his brother in Scotland. He became a close friend of Powell and of Strachan, the two most influential men in the province in his time. As a merchant he generally avoided speculation or excessive risk, probably because of his innate conservatism and his feeling that his stay in Upper Canada was only temporary. By his business ability, the influence of his powerful friends, and the breadth and depth of his public service, he was able to avoid permanent stigma from the 1810 scandal. At his death the British Colonist called him one of Toronto’s “most respected inhabitants.”

AO, MS 6; MS 35; MS 88; MU 2828; MU 4742; RG 22, ser.94; RG 40, D-1. GRO (Edinburgh), Fetteresso, reg. of baptisms, marriages, and burials. MTRL, William Allan papers; Early Toronto papers, Board of Health papers, 20 June 1832; John McGill papers, B40: 42; W. D. Powell papers; Laurent Quetton de St George papers; Alexander Wood papers and letter-books. PAC, RG 5; A1. Royal Canadian Military Institute (Toronto), York garrison accounts. Can., Prov. of, Statutes, 1851, c.168. J. [M.] Lambert, “An American lady in old Toronto: the letters of Julia Lambert, 1821–1854,” ed. S. A. Heward and W. S. Wallace, RSC Trans., 3rd ser., 40 (1946), sect.ii: 101–42. Loyal and Patriotic Soc. of U.C., Explanation of the proceedings (Toronto, 1841); The report of the Loyal and Patriotic Society of Upper Canada; with an appendix, and a list of subscribers and benefactors (Montreal, 1817). “Minutes of the Court of General Quarter Sessions of the Peace for the Home District, 13th March, 1800, to 28th December, 1811,” AO Report, 1932. [W. D. Powell], [A letter from W. D. Powell, chief justice, to Sir Peregrine Maitland, lieutenant-governor of Upper Canada, regarding the appointment of Alexander Wood as a commissioner for the investigation of claims . . .] ([York (Toronto), 1831?]). John Strachan, The John Strachan letter book, 1812–1834, ed. G. W. Spragge (Toronto, 1946). Town of York, 1793–1815 (Firth); 1815–34 (Firth). York, Upper Canada: minutes of town meetings and lists of inhabitants, 1797–1823, ed. Christine Mosser (Toronto, 1984).

British Colonist, 29 Oct., 1 Nov. 1844. Church, 1 Nov. 1844. Examiner (Toronto), 6 Nov. 1844. Toronto Patriot, 1 Nov. 1844. Upper Canada Gazette, 1797–1828. Toronto directory, 1833–34, 1837. One hundred years of history, 1836–1936: St Andrew’s Society, Toronto, ed. John McLaverty (Toronto, 1936), 3–4, 87–88, 103. W. R. Riddell, The life of William Dummer Powell, first judge at Detroit and fifth chief justice of Upper Canada (Lansing, Mich., 1924). Robertson’s landmarks of Toronto, esp. 2: 1007–21. Scadding, Toronto of old (1873). T. W. Acheson, “The nature and structure of York commerce in the 1820s,” CHR, 50 (1969): 406–28. E. G. Firth, “Alexander Wood, merchant of York,” York Pioneer (Toronto), 1958: 5–29. H. P. Gundy, “The family compact at work: the second Heir and Devisee Commission of Upper Canada, 1805–1841,” OH, 66 (1974): 129–46. Douglas McCalla, “The ‘loyalist’ economy of Upper Canada, 1784–1806,” SH, 16 (1983): 279–304.

Cite This Article

Edith G. Firth, “WOOD, ALEXANDER,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 7, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 26, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/wood_alexander_7E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/wood_alexander_7E.html |

| Author of Article: | Edith G. Firth |

| Title of Article: | WOOD, ALEXANDER |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 7 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1988 |

| Year of revision: | 1988 |

| Access Date: | February 26, 2026 |