Source: Link

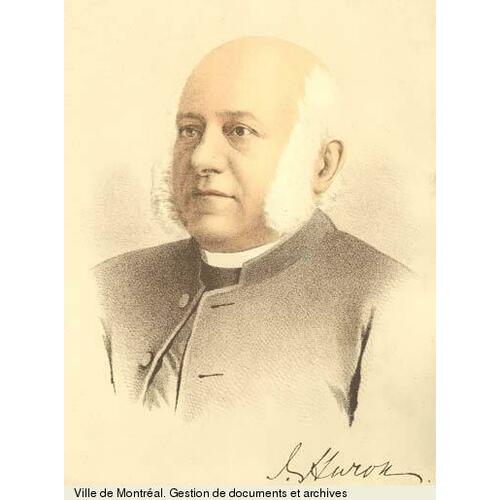

HELLMUTH, ISAAC, Church of England clergyman, bishop, and educator; b. into a Jewish family near Warsaw, probably on 14 Dec. 1817; m. first 12 Jan. 1847 Catherine Maria Evans, daughter of Thomas Evans*, in Montreal, and they had three children; m. secondly 22 June 1886 Mary Louisa Glyn, née Duncombe, in England; d. 28 May 1901 in Weston-super-Mare, England.

Isaac Hellmuth refused to talk about his early life, at least publicly, because he found the memory too painful. He attended rabbinical schools and was apparently expected to become a rabbi like his father. The family moved to Berlin in the early 1830s and Hellmuth entered the university at Breslau (Wrocław, Poland). There, under the influence of a missionary of the Society for the Conversion of the Jews, he became a Christian. That decision resulted in such a complete break with his family that he was induced to assume his mother’s family name; his original surname remains unknown.

Hellmuth emigrated to England in 1842, and for two years he lived in Liverpool at a home giving refuge to Jews contemplating conversion to Christianity. He was baptized in October and later confirmed as a member of the Church of England. By 1844 he had decided to enter the ministry. The churchmanship of the clergy in Liverpool was notoriously low, and even before he had any formal theological training he adopted the extreme evangelical Protestant position he was to hold all of his life. He also perfected his command of English while at Liverpool and began to build up the network of influential friends and acquaintances, both lay and clerical, that he would call upon for assistance in the future.

In late 1844 Hellmuth was sent to the diocese of Toronto, by “some friends in England,” according to John Strachan*, so that he might work among German-speaking settlers. He began to prepare for ordination under the direction of Alexander Neil Bethune* at the Diocesan Theological Institution in Cobourg, Upper Canada, but in the autumn of 1845, with Strachan’s permission, he transferred to Bishop’s College in Lennoxville, Lower Canada. He was ordained deacon on 1 May 1846 and priest on 21 September in Quebec by George Jehoshaphat Mountain*.

Hellmuth’s education provided him with an additional opportunity. Strachan referred to him as a “very superior Hebrew scholar” and in the summer of 1846 Mountain appointed him professor of Hebrew and rabbinical literature at Bishop’s College. He was also given charge of the mission at Sherbrooke. He became rector in 1849 and, having married in 1847, appeared to be settling into a life of teaching and ministering. It did not, however, last long. A quarrel, the origin of which is obscure, with Henry Hopper Miles*, also professor at Bishop’s, seriously disrupted the college until Hellmuth resigned in November 1853. As he left Bishop’s, he was awarded in 1854 an honorary dd (he had received a Lambeth dd the previous year). He also resigned as rector at Sherbrooke and advised Mountain that he was returning to England.

On 1 Oct. 1854 Hellmuth became organizing secretary in London for the Colonial Church and School Society, which provided support for clergy, lay missionaries, catechists, and teachers throughout the British empire. Initially his work, consisting largely of fund-raising, was confined to Britain. Within six months, however, in response to urgent appeals from British North America, Hellmuth was asked to return as general superintendent and to extend the society’s concerns. His departure was delayed but by summer 1856 he had taken up residence in Quebec City. With something of the administrative responsibility of a bishop, he worked to establish branches of the society, visited and encouraged those it employed, and prepared an annual report which he sent to London for publication. In 1860 he oversaw 31 clergymen and 70 lay men and women in eight dioceses stretching from southwestern Upper Canada to the outports of Newfoundland.

Of all the people Hellmuth met through the society, none would have a greater impact on his life than Benjamin Cronyn*, president of the branch in London, Upper Canada. They appear to have met for the first time in 1856 when Hellmuth visited London to prepare a report on the growing population of fugitive slaves in the area. In 1859, after Cronyn had become bishop of Huron, they undertook a visit to the newly Protestant congregation of the Roman Catholic apostate Charles Chiniquy* in Illinois. Perhaps the most telling evidence of their close association is that between 1857 and 1861 13 of the 31 clergy supported by the society had been located in Huron; all of them, no doubt, were thoroughly evangelical in orientation.

Pleading exhaustion from overwork, Hellmuth resigned his position in March 1861. He was almost immediately appointed archdeacon of Huron and bishop’s commissary by Cronyn, who was working to establish a college to prepare evangelical clergy for his diocese. The college would require a considerable amount of money, but because its existence involved a repudiation of Trinity College in Toronto, the prospects for support from Canadian churchmen were limited. What was needed was access to the deep pockets of British evangelicals, which Hellmuth possessed through his extensive contacts. Moreover, he had his own financial resources. His wife’s family was wealthy and he was able to afford frequent transatlantic journeys and long sojourns in Britain. He contributed handsomely to his church throughout his career, and he would serve as rector of St Paul’s Cathedral in London and as bishop without a salary, at least through part of his terms. He had already demonstrated in 1849 his abilities as a fund-raiser when he returned from a visit to his wife’s relations in England with a donation of £1,000 to Bishop’s College.

To raise funds for the college Hellmuth travelled to England in 1861 and 1862. His foraging may have been eased by a controversy that resulted from a speech he made in England in which he deplored the dearth of evangelical clergy in the Canadian church. Bishop Francis Fulford* of Montreal sprang to the defence in three pastoral letters. However, an English clergyman, Alfred Peache, noted in November 1862 that “Dr. Fulford complains of your statement [but] has only given painful and conclusive evidence of its substantive truth.” (Fulford had distrusted Hellmuth since 1850–51 when Thomas Evans had offered financial assistance for the construction of a church for the German-speaking people of Montreal with Hellmuth as the first incumbent, a proposal Fulford had refused.) Hellmuth raised about £23,000 for the college, as well as an endowment of £5,000 from Peache to provide a salary for the principal and professor of divinity. Patronage of the “Peache chair” was to be kept in England, apparently on Hellmuth’s recommendation, in order to ensure that the incumbents would be thoroughly evangelical, and the first person appointed was Hellrnuth himself. He took up his new positions when Huron College opened its doors in 1863.

Nothing occupied Hellmuth’s attention more than educational questions. He continued his connection with Huron College until 1866 when Cronyn appointed him rector of St Paul’s and dean of Huron. By then, however, Hellmuth was involved in two other major undertakings, the London Collegiate Institute (later known as Hellmuth College) for boys, and Hellmuth Ladies’ College, both residential secondary schools. The former, housed in a pretentious four-storey white brick building, was erected at Hellmuth’s expense in 1865 and could accommodate 150 students and staff in more than 70 rooms. Hellmuth Ladies’ College was constructed in 1867 on an equally grand scale. The schools had no official connection with the church but they were thoroughly Anglican. Hellmuth was sole proprietor of the schools and chaired both boards.

In July 1871 Cronyn arranged for the election of a coadjutor bishop with the right of succession. Hellmuth was chosen on the first ballot, receiving 53 out of 84 clerical votes and 78 out of 132 lay votes, and he was consecrated bishop of Norfolk in August. He became second bishop of Huron after Cronyn died in September. With some 12,000 square miles, the diocese of Huron stretched from Waterloo to Windsor and from Long Point to the Bruce peninsula. It included 13 counties and had a population of about 600,000, of whom upwards of 60,000 were Anglican. Hellmuth threw himself into his new tasks with characteristic energy. Indeed, expanding the reach of the church within his diocese was his initial preoccupation and his addresses to synod until the late 1870s contained pleas for more money for diocesan missions. And his actions matched his words: in 1873, for example, he reported that he had ordained 8 deacons and 5 priests, confirmed 1,498 people, consecrated 9 churches, preached 130 sermons, and delivered 105 other addresses. By 1883 the number of priests in the diocese had increased from 92 to 135 and the number of churches from 149 to 207. Not everything he hoped for was realized. One of his first actions as bishop was to launch a campaign to build a massive new cathedral but only a building known as the chapter house was completed.

After 1877 Hellmuth’s attention focused increasingly on the establishment of a university in London. Besides the obvious advantages for the city and for southwestern Ontario, Hellmuth had two other reasons for his growing enthusiasm. In the first place, Huron College students would be able to attend a university to improve their educational level; in fact, Hellmuth argued that without the advantages offered by a university, divinity students would in future shun the college. His other reason was a result of the fact that he possessed in Hellmuth College a massive white elephant. By 1870 he had spent more than $50,000 on the school and yet its future looked bleak. It attracted few students and not many of them had academic ability or ambition. The rapid expansion of provincial high schools, moreover, indicated a limited future for the institution. With the support of Egerton Ryerson* he tried unsuccessfully between 1873 and 1875 to persuade the provincial government to purchase or rent the college in order to convert it into a normal and model school. A proposal in 1874 that the church assume responsibility for the college came to nothing, probably because there was little advantage in making a large expenditure to acquire an institution in poor health. In 1875 Hellmuth and the other trustees obtained a mortgage of $12,000 on the property, presumably for the consolidation of debt, and in 1877 they increased it to $22,000.

An opportunity for Hellmuth came early in 1877 with the establishment of the Association of the Professors and Alumni of Huron College to promote the founding of a university. At a meeting on 20 February the association, with Hellmuth as patron and member of the board, called for the transfer of Hellmuth’s “pecuniary interest” in the school to the association. At its first meeting on 9 May 1878 the senate of the new Western University of London, Ontario, resolved to purchase the property for $67,000. By March 1879 the university owned Hellmuth College but, with a first mortgage of $22,000 as well as a second for $43,450 held by Hellmuth and the other former trustees, the load proved too heavy. Hellmuth and the other holders of the second mortgage were paid off in the mid 1880s but the holders of the first eventually were forced to foreclose.

Hellmuth was at the centre of Western. He petitioned the Ontario legislature for a charter and, in early 1878, appeared before the house to defend the bill to incorporate it. He was appointed chancellor and chairman of the senate, and was professor of biblical exegesis and criticism and of Hebrew and Chaldee. Above all else he was a fund-raiser. By 1883 he had been to Britain five times to raise money. He made a personal donation of $10,000 and urged the diocese to support Western as an institution of the church. Indeed, most of the financial support it received in these early years came from his efforts.

Hellmuth’s work on behalf of the university had another result, this one unfortunate. In February 1879 two letters appeared in the London Evening Herald which strongly attacked him. The education of the students in Hellmuth Ladies’ College was frivolous, vain, and worldly, it was declared, and Hellmuth College, which had been a burden for the church, would also be so for the university, itself a “monumental folly built upon the neglected ruins of Huron College.” Moreover, Hellmuth demonstrably lacked “Christian zeal and toil” for “spiritual matters.” The writer of the second letter was never discovered but the author of the first was identified as Ellinor Schulte, the wife of Professor John Schulte at Huron College; he was forced to make a grovelling public apology and then was dismissed from his position. Archdeacon John Walker Marsh, a member of the Huron College council who first denied any involvement, admitted, when Schulte was tricked by Hellmuth into implicating him, that he had assisted in the publication of the first letter. The Huron College council expelled Marsh and he took the matter to court. In 1880 John Godfrey Spragge* in the Court of Chancery ruled the council’s expulsion of Marsh illegal. Reinstated, Marsh then immediately resigned. Hellmuth emerged from the affair with his reputation tarnished. Instead of ignoring the letters or responding only to the charges they made, he and the Huron College council had conducted a witch-hunt. Except for the anti-Semitism, it is hard to disagree with the judgement of an unknown contemporary who thought that Marsh had been treated “brutally” by the bishop and the council and that Hellmuth had behaved like a “bully” whose conduct disclosed “an extraordinary combination of Jewish cunning and episcopal tyranny.”

Hellmuth resigned as bishop of Huron in 1883 when a friend, Robert Bickersteth, the bishop of Ripon, England, offered him the position of suffragan without the right of succession. The state of his wife’s health may have induced Hellmuth to accept, but it was, in all probability, the sort of appointment he had always wanted. Although he had performed his duties energetically and conscientiously, it seems clear that the diocese of Huron was not his preferred location. The Hellmuths appear to have visited Britain at every possible opportunity, and their travels included the United States, Cuba, Europe, and the Near East. As early as 1878 and again in 1881 he was a candidate for a position involving the supervision of Anglican churches in Europe; as it turned out, no appointment was made and the fact of his application was not made public. But if Hellmuth had expectations of a lengthy episcopal career in Britain, they were not to be realized. Bickersteth died suddenly in the spring of 1884, just after Hellmuth had begun his new duties. Within a month, Catherine Hellmuth also died.

Hellmuth returned to Huron briefly in 1884 but his Canadian career was over. In 1885 Alfred Peache succeeded him as chancellor of Western. Remarried in 1886, for the remainder of his life Hellmuth held a series of undemanding livings in England which were in the gift of evangelical friends. He retired in 1899 to Weston-super-Mare and died there on 28 May 1901.

In addition to polemical letters and sermons, Hellmuth had published a series of eight lectures delivered in 1865, The divine dispensations and their gradual development (London, [Ont.], 1866), which provides a conventional account, based on the inerrancy of Scripture, of the relationships between God, Moses, the Jews, and Christianity. The first volume (“Genesis”) of what Hellmuth intended to be a translation and analysis of the entire Old Testament, entitled Biblical thesaurus, appeared, also in London, in 1884, but no other volumes were published.

In addition to the works mentioned in the text, Isaac Hellmuth wrote three rebuttals to pastoral letters by Bishop Fulford, A reply to a letter of the Rt. Rev. the Lord Bishop of Montreal . . . , Reply to a second letter . . . , and Reply to a third letter . . . , all published at Quebec in 1862. Some of Hellmuth’s publications are listed in Canadiana, 1867–1900 and the CIHM Reg.; additional works are preserved in the ACC, General Synod Arch., Toronto.

ACC, General Synod Arch., M69-2 (J. P. Francis coll.), Roe family papers, uncredited letter dated 10 July 1880. AO, F 983. Middlesex East Land Registry Office (London, Ont.), Abstract index to deeds, City of London, 5: 199; 10: 26–28 (lots 23–27, East Wellington Street) (mfm. at AO). Globe, 12, 14, 26, 28–29 June 1880. Hamilton Spectator, 17 July 1913: 7. Church of England, Diocese of Huron, Journal of the synod (London), 1871–83; Minutes of the synod . . . (London), 1871. Colonial Church and School Soc., Annual report (London, Eng.), 1854/55–1861/62. A. H. Crowfoot, This dreamer; life of Isaac Hellmuth, second bishop of Huron (Vancouver, 1963). DNB. D. C. Masters, Bishop’s University, the first hundred years (Toronto, 1950). J. J. Talman and Ruth Davis Talman, “Western” – 1878–1953: being the history of the origins and development of the University of Western Ontario during its first seventy-five years (London, Ont., 1953). Brian Underwood, Faith at the frontiers: Anglican evangelicals and their countrymen overseas (150 years of the Commonwealth and Continental Church Society) (London, Eng., 1974).

Cite This Article

H. E. Turner, “HELLMUTH, ISAAC,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed July 6, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/hellmuth_isaac_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/hellmuth_isaac_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | H. E. Turner |

| Title of Article: | HELLMUTH, ISAAC |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | July 6, 2025 |