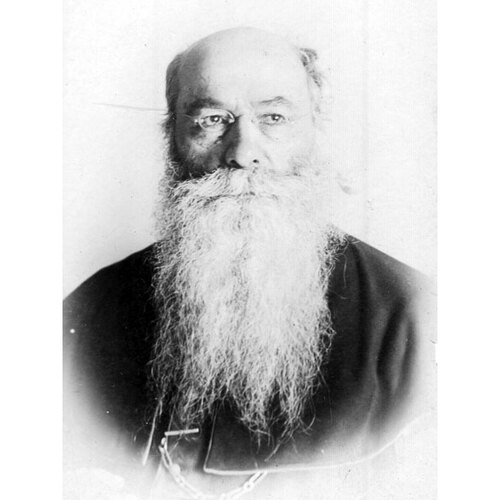

RITCHOT, NOËL-JOSEPH (baptized Joseph-Noël), Roman Catholic priest and missionary; b. 25 Dec. 1825 in L’Assomption, Lower Canada, son of Joseph-Isaïe Ritchot, a farmer, and Marie Riopelle (Riopel); d. 16 March 1905 in St Norbert, Man.

Noël-Joseph Ritchot received his early education at local schools and then worked on the family’s farm. In 1844, at age 18, he enrolled at the College de L’Assomption. According to an obituary, “He always regretted to have waited so long to take this action. Sometimes he would cry as he spoke of the difficulties which he had to meet as a consequence.” Ritchot nevertheless proved to be an able student, and after completing the classical course, he taught in L’Assomption from 1852 to 1854 while studying for the priesthood. He was ordained at L’Assomption on 22 Dec. 1855 and subsequently served at Berthier (Berthierville) in 1856–57. From 1857 to 1861 he taught and looked after the model farm at the college. In 1861 he was sent to the mission of Sainte-Agathe-des-Monts. It was from this last posting that Ritchot volunteered to serve in the northwest under Bishop Alexandre-Antonin Taché* of the diocese of St Boniface. Arriving at the Red River colony (Man.) in early June 1862, Ritchot was sent to the predominantly Métis parish of St Norbert, approximately nine miles south of the bishop’s residence and Upper Fort Garry (Winnipeg), at the forks of the Red and Assiniboine rivers. With the exception of two summers spent establishing a mission in the Qu’Appelle valley in 1866 and 1867, Ritchot would serve that parish until his death.

In the summer of 1869 Ritchot played a critical role during the formative stages of Métis resistance to the proposed transfer of the northwest from the Hudson’s Bay Company to Canada [see Louis Riel*]. Concerned that they had not been consulted and worried about the actions of a number of Canadians who had been seen staking claims near St Norbert, several Métis held an assembly in the parish on 5 July and resolved to protect Métis lands from speculators. As the movement evolved, Ritchot hosted its leaders, including Riel, in his home and billeted the Métis “soldiers” in his church. He acted as a recorder of the deliberations of the Métis, as chaplain to their forces, and as a counsellor to their leaders, particularly Riel. By doing so he gave legitimacy to the movement, in the face of opposition from the local administration of the HBC and from much of the Métis élite, including men such as Charles Nolin. Following the capture of Upper Fort Garry by Riel on 2 November and the establishment of the provisional government later that month, Ritchot’s participation in the movement became less public.

On 11 Feb. 1870, however, Ritchot was once again in the public eye when he was named a delegate to the Canadian government in Ottawa, together with John Black*, president of the General Quarterly Court of Assiniboia, and Alfred Henry Scott*, a clerk. Black was to represent the English-speaking element in the colony, Scott the Americans, and Ritchot the Métis. Their task was to negotiate the entry of the Red River colony into confederation, based on the “List of Rights” prepared by the executive of the provisional government, in fact the third such list drafted. It provided, among other things, for the establishment of a province, provincial control of public lands, the use of English and French in the legislature, the courts, and public documents, a bilingual lieutenant governor and judge, and an amnesty for all members of the provisional government and those who acted on its behalf. Before Ritchot left the colony on 24 March, he received a fourth version of the list, adding separate schools to the demands, probably at the request of Bishop Taché, and specifying the structure of the new provincial government.

On his arrival in Ottawa Ritchot was arrested on a private warrant for complicity in the death of Thomas Scott*, but he was soon released for lack of evidence. The delegates began discussions in earnest with Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald* and Sir George-Étienne Cartier* on 25 April in Cartier’s home. The forceful Ritchot proved to be an able negotiator. He soon secured provincial status for the colony, along with the establishment of bilingual and bicultural institutions. The province would comprise only the Red River settlement and would not control its public lands and resources, but Ritchot succeeded in having 1,400,000 acres of land set aside for the Métis in recognition of their aboriginal rights. The results of the secret negotiations were embodied in the articles of the Manitoba Act, which was introduced in the House of Commons on 4 May. Ritchot also believed he had obtained guarantees for the rapid settlement of Métis and other land claims by local officials and, as a sine qua non for commencing the talks, a general amnesty for all involved in the resistance. Although the bill passed and received royal assent on 12 May, Ritchot was compelled to remain in Ottawa another month in a vain attempt to secure written guarantees of the amnesty promised by Cartier and Macdonald and reassurances as to the nature of the military force to be sent from Canada under Colonel Garnet Joseph Wolseley*. Given verbal assurances by the governor general, Sir John Young*, and ambiguous notes by Cartier, he returned to the Red River settlement, where on 24 June he outlined the proffered terms of confederation to a public assembly. He persuaded the settlers to accept the arrangements and not to oppose the arrival of the military expedition.

When it became apparent that Riel and other Métis were not to receive an amnesty and that the settlement of land claims was to take years and not months, Ritchot felt betrayed. On several occasions during the 1870s he returned to Ottawa in an effort to have the Canadian government live up to the terms and spirit of its agreement. During the same period he worked to try to keep the Métis from moving further west. When that attempt failed, he purchased many of their river lots within his parish and eventually resold them to incoming French Canadians or other Roman Catholics. Between 1867 and 1900 he purchased 45 of the 256 river lots surveyed in St Norbert. The profits were used to provide mortgages and personal loans to his parishioners.

Ritchot spent the remainder of his ministry working to bring to his parish religious and educational institutions which eventually would be second only to those found in St Boniface. In 1883 he built a new parish church. He was instrumental in persuading the Trappists to come to St Norbert, providing land and funds for the monastery of Notre-Dame-des-Prairies, founded in 1892. He encouraged the educational work of the Sisters of Charity of the Hôpital Général of Montreal and the establishment of the Asile Bethléem, an institution for abandoned infants, by the Sisters of Miséricorde. Even after his death his land-based wealth continued to be used for educational and charitable purposes. The executor of his estate reported the distribution of over $100,000 between 1905 and 1925.

In 1897 Ritchot was named apostolic prothonotary and sometime earlier he had been made vicar general. By the time of his death he was the senior member of the secular clergy in the diocese of St Boniface. Like many of the Red River clergy of all denominations, Ritchot had been a willing participant in the events of 1869–70. His closeness to Riel, his participation in the early decision-making of the Métis militants, and his role as the principal negotiator of Manitoba’s entry into confederation, however, distinguished him from others, including his more moderate bishop. Seeking to preserve the rights of the Métis and to secure their future under Canadian rule, he had fought tenaciously for guarantees regarding their lands, their aboriginal rights, and the physical safety of their political leadership. He thus earned their respect, despite the failure of Ottawa and Manitoba to live up to the text of the Manitoba Act and the spirit of the negotiations. Ritchot’s significance has been recognized in the publication of his Ottawa journal and in passing references in the historiography of Red River. Riel was probably the most aware of Ritchot’s contribution. In his last known letter to the priest the Métis leader wrote, “And in walking in the footsteps of a man such as you Father, I tried to base my conduct on the one hand on what I am asked to do for others and on the other on what I am obliged in conscience to do for them.”

[Noël-Joseph Ritchot’s papers and letters are dispersed among the AASB, the parish archives of Saint-Norbert, Man., and PAM, MG 3, B14-1 and B14-2. Some of the items in these collections appear in Can., House of Commons, Select committee on the causes of the difficulties in the North-West Territory in 1869–70, Report (Ottawa, 1874). The journal Ritchot kept while he was in Ottawa was published as “Documents inédits, I: le journal de l’abbé N.-J. Ritchot, 1870,” intro. G. F. G. Stanley, RHAF, 17 (1963–64): 537–64; it was translated into English by William Lewis Morton* as “The journal of Rev. N.-J. Ritchot, March 24 to May 28, 1870,” in Manitoba: the birth of a province, ed. W. L. Morton (Altona, Man., 1965), 131–60. The only full biography of Ritchot, L.-A. Prud’homme, Monseigneur Noël-Joseph Ritchot, vicaire général, protonotaire apostolique, curé de la paroisse de Saint-Norbert, 1825–1905 (Winnipeg, 1928), is for the most part hagiographical and supplies little detail on his political and real estate activities. A more complete picture of his secular career appears in my study, “Ritchot’s resistance: Abbé Noël Joseph Ritchot and the creation and transformation of Manitoba” (phd thesis, Univ. of Manitoba, Winnipeg, 1986).

See also AP, L’Assomption-de-la-Sainte-Vierge (L’Assomption, Qué.), RBMS, 26 déc. 1825; Manitoba Morning Free Press, 17 March 1905; and Anastase Forget, Histoire du collège de L’Assomption; 1833 – un siècle – 1933 (Montréal, [1933]). p.r.m.]

Cite This Article

Philippe R. Mailhot, “RITCHOT, NOËL-JOSEPH (baptized Joseph-Noël),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 2, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/ritchot_noel_joseph_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/ritchot_noel_joseph_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | Philippe R. Mailhot |

| Title of Article: | RITCHOT, NOËL-JOSEPH (baptized Joseph-Noël) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1994 |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | March 2, 2026 |