NOLIN, CHARLES, Métis farmer, fur trader, and politician; b. 1837 in St Boniface (Man.), son of Augustin Nolin and Hélène-Anne Cameron; m. first Marie-Anne Harrison (d. 1877); m. secondly Rosalie Lépine, widow of Godefroi Lagimodière; from the two marriages he had at least eleven children and he adopted two sons; d. 28 Jan. 1907 at Outarde (Goose) Lake, near Battleford, Sask.

Charles Nolin’s grandfather Jean-Baptiste Nolin* left Saint-Pierre, Île d’Orléans, in the province of Quebec, for the fur trade of the pays d’en haut in the 1770s. He married Marie-Angélique Couvret, whose mother was Ojibwa, and established himself as a trader at Sault Ste Marie (Mich.). By 1820 his son Augustin had made his way to Pembina (N.Dak.), and he eventually settled at St Boniface in the Red River settlement (Man.). The Nolin family was later reported to be affluent and enterprising. Charles attended primary school at the mission of St Boniface but his letters suggest that he obtained a limited education. He and his brothers Joseph and Duncan became farmers and traders in Pointe-de-Chêne (Ste-Anne-des-Chênes) in the 1850s.

By the late 1860s the prosperous Nolin brothers identified politically with the more conservative or “loyalist” Métis who supported the Council of Assiniboia and the proposed transfer of Rupert’s Land to Canada. This loyalist group also included the Brelands [see Pascal Breland*], the Hamelins, and their relatives. Opposed to the annexation were the Riels, the Lépines, and the Naults [see Louis Riel*; Jean-Baptiste Lépine*; André Nault*]. Riel and his supporters advocated a negotiated agreement with guarantees for the land and the political rights of the Métis. In December 1869 Nolin and his brothers met with Lieutenant-Colonel John Stoughton Dennis*, a representative of the lieutenant governor designate, William McDougall. Dennis had been given the authority to raise an army to put down the “resisters” and he enrolled the Nolins. His attempts to suppress the resistance failed and he fled the colony on 11 December.

Ultimately, Nolin became involved in the provisional government that Riel had set up to replace the Council of Assiniboia. Representing Ste-Anne-des-Chênes, Nolin was one of 20 French-speaking delegates elected to a convention called by Riel which first met on 26 Jan. 1870, and he was appointed to its executive committee. At this time an intense rivalry between Nolin and Riel began to develop. Nolin disagreed with Riel’s proposal that the region be granted provincial status, put forth on 3 February, and he evidently resented his ascendancy over the Métis. The quarrel escalated and Riel even attempted to have him arrested. Nolin reluctantly agreed to support the provisional government and its leader. He was elected later in February to the 24-member assembly that had been established by the convention, but he was soon removed from it and jailed for a short time. After the adoption of the Manitoba Act in May 1870, Riel visited Ste-Anne-des-Chênes in hope of a reconciliation. The animosity between the two factions was so great, however, that the Nolin family threatened him. Roman Catholic bishop Alexandre-Antonin Taché* subsequently intervened to bring about peace between the two men, cousins by marriage. In March 1871 Nolin wrote a letter of apology to Riel and there was renewed solidarity among the Métis.

Whether Nolin’s reconciliation with Riel was motivated primarily by a desire to advance his own political interests is not clear. Despite his efforts, he was unsuccessful in his bid to represent Ste Anne in Manitoba’s first provincial election, held in December 1870. He was unable to gain the support of the local priest, Louis-Raymond Giroux, or that of many Métis. In October 1871 he led the Métis contingent from Ste-Anne-des-Chênes raised during the Fenian scare [see William Bernard O’Donoghue*] and he met with Riel and other Métis in St Vital to discuss Métis rights and political representation. He supported Riel’s candidacy for the federal riding of Provencher in 1873 and after Riel went into exile he tried, without success, to assume the leadership of the Métis.

There was growing tension between the “old order” and the “new order” in Manitoba in the 1870s. Not only were the English-speaking immigrants from Ontario antagonistic towards the Métis, but there were difficulties within the French-speaking community as well. French Canadian newcomers such as Joseph Royal, Joseph Dubuc*, and Marc-Amable Girard*, all of whom aspired to the leadership of the “French party,” were favoured over traditional Métis leaders by Taché and some priests. Indeed, Girard became Manitoba’s first premier in July 1874. During the provincial election campaign the following December Nolin circulated a petition in favour of a Métis candidate rather than a French Canadian. He was critical of Girard’s weak ministry and of French Canadian politicians in general. He enjoyed a good political fight and according to his opponents he was not above resorting to unscrupulous actions. In the same election he contested Ste Anne against Alphonse-Alfred-Clément La Rivière*. Despite the intervention of Abbé Giroux, Nolin received 69 votes and La Rivière 29. The gap between French Canadians and Métis would become even more pronounced in the following years.

In March 1875 Nolin was appointed minister of agriculture by Premier Robert Atkinson Davis, a crucial post during the period of Métis land claims and increasing immigration from Europe and the rest of Canada. Nolin became the most prominent Métis politician and dispenser of patronage; his influence and prestige brought him government contracts. During the negotiations with the Ojibwa that had led to the signing of Treaty No.3 in 1873, he had acted as interpreter for Lieutenant Governor Alexander Morris*. Although an agent of the government, he had disapproved of its treatment of the natives. Now, as minister, he deplored the lack of assistance available to the Métis in the government’s agricultural policies. In protest, he resigned as minister in December 1875 and sat as an independent until 1878. He worked for the cancellation of dominion relief loans taken out by poor Métis farmers and was openly critical of the administration of Métis scrip. Reelected in Ste Anne in December 1878 after a particularly heated campaign against a French Canadian candidate, Nolin, with his agents, was charged with bribery and corrupt practices.

Not to be contained, however, Nolin was soon involved in another controversial event. In the spring of 1879 he and a group of Métis in the assembly resolved to defeat the government of John Norquay* but their attempted coup was usurped by Royal, the self-styled leader of the French party. Royal’s venture failed when a Métis faction led by Nolin refused to support him and the French Canadians in their effort to break an alliance of the English-speaking members. There was much conflict among Métis, French Canadians, and English-speaking groups of both native and English Canadian ancestry in the late 1870s, as they sought new alliances and jostled for power. Ultimately, the increasingly numerous English-speaking representatives defeated or dispersed the divided French-speaking politicians. The Métis were the biggest losers. By June Nolin had been found guilty of the charges arising from the election of 1878 and he was severely reprimanded. Later that year, humiliated and debt-ridden, he left for the Touchwood Hills (Sask.). His political colleagues Louis Schmidt and Maxime Lépine* would follow shortly.

Nolin lived for three years on a homestead in the Touchwood Hills. His property consisted of a house, stable, store, storehouse, and small schoolhouse. In 1881 he had 12 acres under cultivation. He farmed, traded in furs, and operated a school for the scattered Métis settlers of the district. He moved north to a farm halfway between Saint-Laurent-de-Grandin (St Laurent-Grandin) and St Louis in 1883. With his neighbour Lépine he operated a ferry service. On his arrival in the South Saskatchewan River district he had organized secret meetings to discuss Métis grievances regarding land claims and other issues and had become involved in the preparation of petitions to the government. Along with Lépine, Michel Dumas, and Gabriel Dumont, he headed the movement to defend the rights of the Métis. Nolin strongly supported the resolution to invite Riel to return as leader. After he arrived in July 1884 Riel resided with Nolin and during the next few months the two were inseparable. Nolin was an early advocate of armed resistance and he helped draft the petition of December 1884 outlining the grievances of the Métis and the Indians in the northwest. But his militancy and support of Riel suddenly wavered in the face of opposition by the clergy and the miraculous cure of his wife following a novena later that month. Other factors, such as resentment of Riel’s influence, fear, and mistrust, probably also came into play. Nolin became a member of Riel’s council, or exovedate, in March 1885 but his behaviour and actions were equivocal. The council accused him of treason and condemned him to death. A reconciliation was achieved and Nolin was given two important missions. On 21 March he was asked to deliver an ultimatum to Superintendent Lief Newry Fitzroy Crozier of the North-West Mounted Police; he presented it to Crozier’s representatives the same day. Two days later he was assigned to enrol in the Métis cause English “Halfbreeds” living near Prince Albert. It was evident, however, that he was subverting the provisional government. He fled to Prince Albert during the battle of Duck Lake on 26 March but was promptly arrested and jailed by the NWMP. His wife and young children sought refuge with the priests at Batoche. In exchange for his freedom at the end of the hostilities Nolin agreed to become one of the crown’s chief witnesses against Riel. His testimony was particularly vindictive and ultimately isolated him from the rest of the community, which branded him a “turncoat.”

Nolin maintained his association with the more conservative Métis and was rewarded by Conservative governments with patronage appointments and contracts. He was made a justice of the peace and was a principal signatory to a petition prepared by the Métis Conservatives of the South Saskatchewan River district in 1888. In 1891 he unsuccessfully sought election for Batoche in the Legislative Assembly of the North-West Territories against Charles-Eugène Boucher, a dynamic young Métis. Nolin and his associates were found guilty of bribery and fraud. The election caused much division in the Métis community and marked the final episode of his tumultuous political career.

He remained involved in social and cultural activities, such as the yearly Fête des Métifs, but concentrated on the expansion of his farm. In 1895 he and his sons were wintering cattle south of the Thunderchild Indian Reserve near Battleford. In the federal election of 1896 he supported the Liberal party and was appointed farmer-instructor at the One Arrow Indian Reserve [see Kāpeyakwāskonam*], near Batoche. Local opposition forced his withdrawal, however. By 1901 he and his family had relocated to a ranch at Outarde Lake, where he died six years later.

Nolin was a Métis leader who, along with Riel, Lépine, and Dumont, was genuinely interested in the promotion of his people’s rights and interests. He was reputed to be a generous host and a good singer and storyteller. But he was also a pugnacious and pompous man whose political actions were marked by inconsistency. Perhaps his biggest misfortune was that he lived, like Riel’s secretary, Schmidt, “in the shadow of greatness.”

AASB, Fonds Picton, notes généal. et dossier Nolin; Fonds Taché; Journal de Gabriel Cloutier, 2: 5152, 5174–76. Man., Culture, Heritage and Recreation, Hist. Resources Branch (Winnipeg), Jerry Lemay, “Charles Nolin, bourgeois Métis, 1837–1907” (typescript, n.p., 1979). NA, MG 26, G: 672, 677, 681. PAM, MG 3, D1, 274. Saskatchewan Arch. Board (Saskatoon), Homestead files, 44995, 897776. Le Métis (Saint-Boniface), 26 juin 1879. Prince Albert Advocate (Prince Albert, Sask.), 11 May 1897. Saskatchewan Herald (Battleford), 27 Nov. 1891, 1 Nov. 1895. Alexander Begg, Alexander Begg’s Red River journal and other papers relative to the Red River resistance of 1869–1870, ed. W. L. Morton (Toronto, 1956). Marcel Giraud, Le Métis canadien; son rôle dans l’histoire des provinces de l’Ouest (Paris, 1945). R. J. A. Huel, “Living in the shadow of greatness: Louis Schmidt, Riel’s secretary,” Native Studies Rev. (Saskatoon), 1 (1984): 16–27. Man., Legislative Assembly, Journals, 2 June 1879. Morris, Treaties of Canada with the Indians. N.W.T., Legislative Assembly, Journals, 1891–92. Robert Painchaud, “Les rapports entre les Métis et les Canadiens français au Manitoba, 1870–1884,” The other natives, the Métis, ed. A. S. Lussier and D. B. Sealey (3v., Winnipeg, 1978–80), 2: 53–74. The Queen v Louis Riel, intro. Desmond Morton (Toronto and Buffalo, N.Y., 1974). Louis Riel, The collected writings of Louis Riel, ed. G. F. G. Stanley (5v., Edmonton, 1985).

Cite This Article

Diane P. Payment, “NOLIN, CHARLES,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 18, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/nolin_charles_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/nolin_charles_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | Diane P. Payment |

| Title of Article: | NOLIN, CHARLES |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1994 |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | December 18, 2025 |

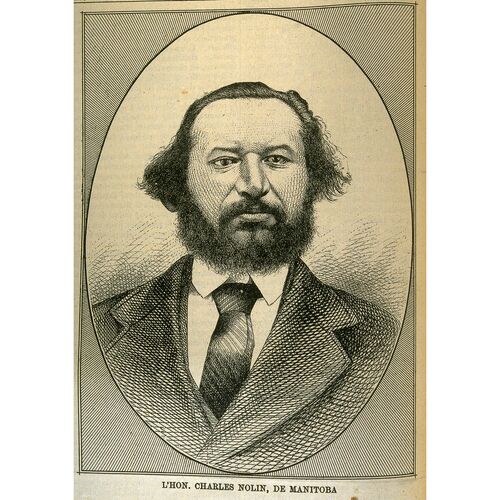

![L'Hon. Charles Nolin, de Manitoba [image fixe] Original title: L'Hon. Charles Nolin, de Manitoba [image fixe]](/bioimages/w600.6326.jpg)