Source: Link

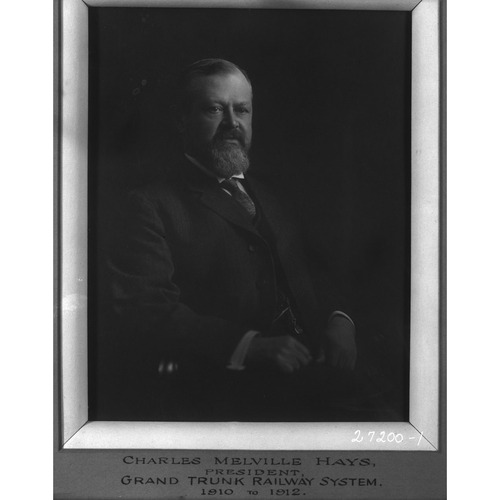

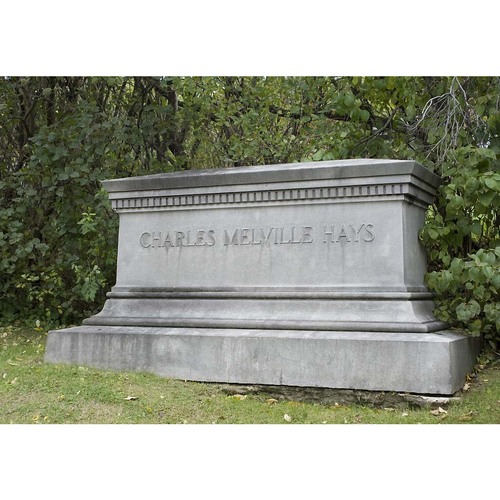

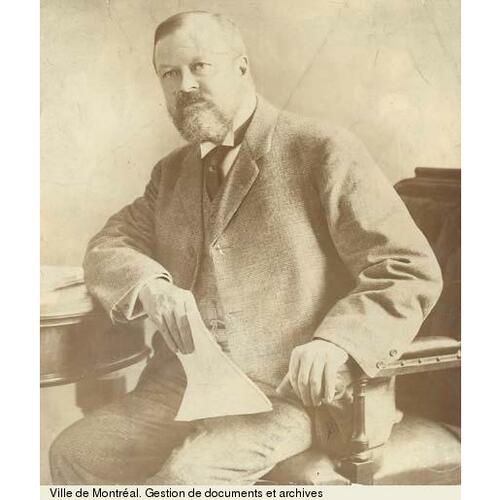

HAYS, CHARLES MELVILLE, railway official; b. 16 May 1856 in Rock Island, Ill.; m. 13 Oct. 1881 Clara J. Gregg in St Louis, Mo., and they had four daughters; d. 15 April 1912 in the North Atlantic, and was buried in Montreal.

Charles M. Hays grew up and received his early education in St Joseph, Mo. At 17 he began work in St Louis with the Atlantic and Pacific Railroad. In 1878 he was appointed secretary to the general manager of the Missouri Pacific and six years later he accepted a similar position with the larger Wabash, St Louis and Pacific. He became general manager of the Wabash Western in 1887 and of the entire Wabash system in 1889.

A reorganization of the Grand Trunk Railway of Canada in 1895 resulted in Hays’s appointment as general manager of that system, effective 1 Jan. 1896, and his move with his family to Montreal. His predecessor, Lewis James Seargeant, became a special adviser to the GTR’s London-based board of directors. With one interruption, in 1901, Hays held his position until 1909, when he was appointed president; he was president as well of the railway’s western Canadian subsidiary, the Grand Trunk Pacific, from 1904 until his death.

He had arrived in Canada at a time of economic depression. The performance of railways had been disappointing for years, although the Canadian Pacific Railway had fared better than the larger, more heavily indebted GTR. Hays was brought in to make major managerial changes – specifically to introduce “American” methods which were more aggressive and less scrupulous than those of British systems. His first responsibility was to restructure the GTR’s administration and operations. Instead of relying only on the reports and recommendations of senior administrators in Britain, he sought the opinions and advice of operating staff in Canada. Traffic exchanges with other systems, the negotiation of running rights, and the modernization of accounting procedures solved many of the practical problems left unaddressed by the head office. Hays was even willing to sell important trackage between Toronto and Hamilton to the rival CPR, but only after the GTR had obtained an advantageous agreement on running rights. The improved efficiency resulting from these reforms coincided with an era of unprecedented growth and enabled him to bring the GTR from a state of near-bankruptcy to one of moderate success. In the process, Hays, a stocky man who invariably appeared well dressed with a neat beard, became known for his unwillingness to tolerate any interference in the way he ran the railway and for his implacable disdain for organized labour, especially during a dispute in Ontario in 1905 and a bitter, system-wide strike in 1910.

After 1896 Canadian prosperity was based on the settlement of the prairies. To compete effectively with the CPR, Hays believed the GTR had to cross them. In 1900 he had advanced a grandiose plan to run the lines of an American subsidiary, the Grand Trunk Western, from Chicago to Winnipeg and thence to the Pacific. The directors in London rejected this proposal and in late 1900 Hays resigned to become president of the Southern Pacific Railroad in the United States as of 1 Jan. 1901. Unfortunately for him, it was taken over by the interests of railway magnate Edward Henry Harriman. Hays disagreed with the new owners and quit; by the end of 1901 he had returned to his old job, and a vice-presidency, at the GTR. In the meantime its board had been persuaded by president Sir Charles Rivers Wilson to adopt an aggressive policy of westward expansion. Significantly too, the federal government of Sir Wilfrid Laurier had decided to promote the building of a second transcontinental railway. On the failure of the GTR and the smaller, prairie-based Canadian Northern to unite on such a project, Ottawa threw its support behind the GTR. On 24 Nov. 1902 Hays formally announced plans to construct a transcontinental.

The Grand Trunk Pacific, Hays’s greatest and most controversial work in Canada, was to consist of two sections: a line west from Winnipeg and a government-built line between Winnipeg and Moncton, N.B., that was to connect with the old Grand Trunk system. Hays was responsible for the construction and operation policies of the new western line. His persistent demands for federal subsidization, however, contributed to bitter discord within Laurier’s cabinet [see Andrew George Blair*], which could not agree on a policy. In May 1903 Hays was joined by president Sir Charles Wilson, who was able to exert greater influence on cabinet; together they formed an effective team, one tough, the other smooth. Hays was willing to promise whatever Wilson thought diplomatically necessary, but he did so only if there were no real means for the government to enforce terms that the GTP might find inconvenient in the future. Nevertheless, his concessions were critically important in meeting specific political difficulties faced by Laurier when he was promoting the transcontinental scheme in parliament that summer and fall. In October the National Transcontinental Railway Act was passed and the GTP was incorporated.

Four aspects of Hays’s GTP policies were particularly problematic. He seriously underestimated the Canadian Northern, whose owners he thought would sell out to him but who, instead, launched vigorous competition. A second, more difficult matter was the commitment of the GTR to the GTP. There were no existing traffic links between the two systems, and the board in London was not willing to give the western project its unqualified support. Nevertheless, Hays, acting without proper authorization from London, committed the parent company in 1903 to conditions which would ultimately ruin the GTP and the Grand Trunk. The selection in 1905 of the site of Prince Rupert, on Kaien Island, B.C., as the western terminal was the third controversial decision supported by Hays. There was little local traffic on the portion of the line in northern British Columbia, only 100 miles of which had been built by 1912, but Hays insisted that it would prove beneficial since it shortened the route to Asia.

A final, disastrous decision involved the priority Hays gave to the construction of the GTP to the highest standards in North America, before a system of feeders had been developed on the prairies. The resulting delay in completion and the lack of competition allowed the CPR and the Canadian Northern to consolidate their holds on traffic on the prairies. Consequently, what was arguably the best main line across western Canada did not attract the volume of freight needed for profitable operation.

Hays did not live to see the GTP completed: he perished in the sinking of the Titanic in 1912. Sanctified by this tragic end and by his high social standing in Montreal, including membership in the American Presbyterian Church, he was eulogized as one of Canada’s greatest railwaymen. On 25 April 1912 work and movement on the GTR’s entire system stopped for five minutes in tribute. Hays’s legacy, however, was mixed. He presided over the most prosperous era in the history of the GTR, but as president of the GTP he initiated policies and programs which led in 1919 to the GTP being placed in receivership and to legislation authorizing federal acquisition of the GTR’s capital stock. During the proceedings of the board appointed to value this stock, it was alleged that Hays had deceived the London directors in 1903 and that they had never knowingly endorsed the scheme that led to the insolvency and nationalization of the entire system.

Much of the information in this biography was drawn from the Hays papers at NA, MG 30, A18 (transcripts), and from articles in contemporary railway journals, in particular the Railway and Shipping World (Toronto), 1898–1905, and its successor, the Railway and Marine World, 1906–12.

Gazette (Montreal), 19, 22–23, 26 April 1912. Canadian annual rev. (Hopkins). Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1898 and 1912). A. W. Currie, The Grand Trunk Railway of Canada (Toronto, 1957). Encyclopaedia of Canadian biography . . . (3v., Montreal and Toronto, 1904–7), 1. Frank Leonard, A thousand blunders: the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway and northern British Columbia (Vancouver, 1996). Donald MacKay, The people’s railway; a history of Canadian National (Vancouver and Toronto, 1992). Gavin Murphy, “Canada’s forgotten railway tycoon,” Beaver, 73 (1993–94), no.6: 29–36. T. D. Regehr, The Canadian Northern Railway, pioneer road of the northern prairies, 1895–1918 (Toronto, 1976). Standard dict. of Canadian biog. (Roberts and Tunnell), vol.1. G. R. Stevens, Canadian National Railways (2v., Toronto and Vancouver, 1960–62), 2.

Cite This Article

Theodore D. Regehr, “HAYS, CHARLES MELVILLE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed July 18, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/hays_charles_melville_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/hays_charles_melville_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | Theodore D. Regehr |

| Title of Article: | HAYS, CHARLES MELVILLE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1998 |

| Access Date: | July 18, 2025 |