Source: Link

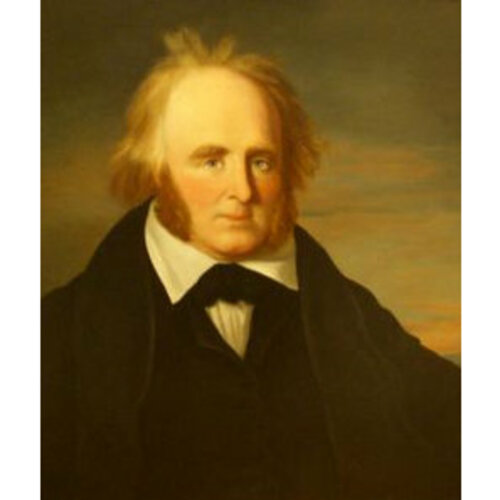

DUNLOP, WILLIAM, known as Tiger Dunlop, army officer, surgeon, Canada Company official, author, jp, militia officer, politician, and office holder; b. 19 Nov. 1792 in Greenock, Scotland, third son of Alexander Dunlop and Janet Graham; d. unmarried 29 June 1848 in Côte-Saint-Paul (Montreal), and was buried first in Hamilton and then in Goderich, Upper Canada.

William Dunlop, the son of a local banker, was educated in Greenock, and pursued his medical studies at the University of Glasgow and in London. He passed his army medical examinations in December 1812 and was appointed assistant surgeon to the 89th Foot on 4 Feb. 1813. Later that year he arrived in Upper Canada, during the War of 1812, in time to treat men wounded at both Crysler’s Farm and Lundy’s Lane. According to his friend James FitzGibbon*, he played a more active role in the assault on Fort Erie on 15 Aug. 1814, carrying about a dozen injured men out of the range of fire and refreshing weary survivors from canteens filled with wine. He was serving with a road-cutting party near Penetanguishene in the spring of 1815 when he received “the appalling intelligence that peace had been concluded.”

Despite having a “good war,” Dunlop found army life not wholly to his liking, and, after retiring on half pay on 25 Jan. 1817, he led a peripatetic existence. He went first to India where, as a journalist and editor in Calcutta, he took a hand in forcing the relaxation of press censorship. His unsuccessful attempt to clear tigers from Sagar Island in the Bay of Bengal, in an effort to turn the place into a tourist resort, provided him with his famous nickname. Dunlop returned to Scotland in the spring of 1820 because of a fever contracted on Sagar. From Rothesay he contributed to Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine a series of sketches based on his experiences in India. In 1823 he lectured in Edinburgh on the fledgling science of medical jurisprudence. The following year he departed for London, where he was editor, briefly, of the daily British Press and where, in December, he established his own paper, the Telescope, which ran until December 1825.

By 1824 the Scottish novelist John Galt was constructing a huge land and colonization organization intended to operate in Upper Canada. It was finally chartered in 1826 as the Canada Company and later that year Dunlop, who had submitted to Galt a plan for assisting potential emigrants, was taken on under the exalted title of warden of the woods and forests. His official task was to inspect the Canadian lands the company had contracted for (eventually they would purchase some two and a half million acres), determine which lots might be sold quickly, investigate squatters on company lands, and “stop the spoliation of the timber.” The company thought Dunlop “singularly well qualified” for this enormous job; his pay was to be the equivalent of that of an infantry captain.

Dunlop arrived in the colony in late 1826 and, at least until Galt left the firm in 1829, he bustled about performing his official duties and other self-appointed tasks as a kind of travelling factotum. Present at the much-celebrated founding of Guelph in April 1827, that summer he travelled through the bush to the future site of Goderich and the following year accompanied a party of road-cutters to the spot. He soon established his own home, Gairbraid, just north of Goderich across the Maitland River, and took his place among the local élite (he had received his first of many commissions of the peace in June 1827).

In the early years of his employment, Dunlop bristled with schemes for the company’s advantage. Not a few were impractical, such as his idea for the company’s canalization of the Rivière de la Petite Nation between the Ottawa and the St Lawrence. Though he was never a strict party man, Dunlop’s political sympathies ran to the tory side; none the less he managed to annoy leading representatives of both poles of political opinion in Upper Canada. By 1827 he was already receiving unfavourable notice in William Lyon Mackenzie*’s Colonial Advocate. The same year marked the appearance of John Strachan*’s Observations on the provision made for the maintenance of a Protestant clergy. Dunlop’s contribution to the ensuing controversy took the form of a public letter, signed Peter Poundtext, in which, with a mocking grin, he addressed Strachan as “Dear Doctor,” “Dear Friend,” “O celestial Doctor,” and “O Theophilus.” His participation was no doubt motivated as much by his desire to defend the Canada Company’s position as by his love of literary brawling.

In 1829, following a dispute with company directors, John Galt resigned and was replaced by William Allan*, the firm financial pillar of the “family compact,” and Thomas Mercer Jones*, an energetic protégé of Edward Ellice*. The company considered recalling Dunlop along with Galt (whom he continued to support) but Allan and Jones both thought him “beneficial” and “indefatigable.” So he remained in the company’s service and by 1832 he was given power of attorney to execute title deeds. A year later he became resident general superintendent of the Huron Tract (at a raised salary of £400 with an additional £100 for travelling expenses).

The year 1832 saw publication of his guide for emigrants, Statistical sketches of Upper Canada, an event that, along with newspaper skirmishes with Mackenzie following a riot in York (Toronto) on 23 March, helped put him back on public view. This engaging book, written under the pseudonym A Backwoodsman, mixes some (small) practical advice with much tomfoolery and fully exploits the author’s humorous persona. In his chapter on climate, for example, Dunlop says that Upper Canada “may be pronounced the most healthy country under the sun, considering that whisky can be procured for about one shilling sterling per gallon.” The book’s aim was to attract clever young people to Upper Canada, and in that it was not without success: publisher Samuel Thompson* later remarked that he had determined in 1832 to set out for Canada “in the expectation of a good deal of fun of the kind described by Dr. Dunlop.” The more sober-sided directorate of the Canada Company had hoped for something a little more serious but still they underwrote it, read it, and pronounced it both “interesting” and “very amusing.”

Dunlop spent the winter of 1832–33 in Britain, conferring with his superiors in the Canada Company and visiting friends and family. When he returned to Upper Canada in the spring, he brought with him his brother Robert Graham. The pair lived more or less quietly at Gairbraid, though after briefly serving the Canada Company Robert went on to become Huron County’s first member of the House of Assembly.

William was very much a company man during this period. In fact it was probably his able, precise testimony in 1835 at Mackenzie’s muckraking inquiry for the assembly (resulting in The seventh report from the select committee on grievances) that prevented the company from being smeared and brought to Colonial Office notice. Dunlop arranged publication of his own views the following year in a pamphlet, Defence of the Canada Company.

In a roundabout way, however, Mackenzie would be responsible for Dunlop’s breaking with the company. During the rebellion in Upper Canada in 1837–38, Dunlop raised a militia unit, whose nickname, The Bloody Useless, gives a clue to the important role it played. Dunlop, however, doubtless relishing a sense of emergency, commandeered supplies and food for the unit from Canada Company stores. Thomas Mercer Jones was incensed and demanded Dunlop’s withdrawal from the militia. Dunlop, equally angered, instead quit the company in January 1838. Despite protestations from Dunlop’s brother and other influential settlers, the company directors in London upheld Jones’s action. Evidently the directors had decided that they wanted a lower profile in the community than the irrepressible Dunlop exhibited. He had served the company well in many capacities, and had given it credibility and colour at a time when it needed both, but as its activities became more routine and conventional he had become less enchanted with it.

Dunlop’s resignation further widened a growing schism between two factions in Huron County: those for and those against the Canada Company. He became the natural leader of the anti-company faction, known as the Colbornites, since many of them lived in Colborne Township. In February 1841 Robert Dunlop, who had represented Huron in the assembly since 1835, died. In the election later that year (after the union of Upper and Lower Canada), William ran in his place against the Canada Company’s choice, James McGill Strachan*, son of the bishop and brother-in-law of Jones. Despite the British Colonist’s assertion that Strachan had “no more chance, than a stump tailed ox in fly time,” at the close of the vote he was declared elected. Dunlop, however, protested and was awarded the seat; in the general election of 1844 Dunlop ran unopposed.

In the legislature he took a moderate tory stance, and his speeches are frequently more notable for their humour than for their grasp of the issues. In 1841 he chaired a committee to hear the grievances of the exiled radical Robert Fleming Gourlay*, and the report he wrote is both temperate and humane. His most-quoted political maxim had been written, however, in October 1839. In a letter published in the Kingston Chronicle & Gazette, he declared that responsible government was “a trap set by knaves to catch fools.” The phrase soon became something of a rallying cry for the opponents of responsible government.

During his years in parliament Dunlop also served as the first warden of the district of Huron. His methods were sometimes high-handed, and he embroiled himself and the district council in an unfortunate dispute with the Canada Company over taxation, which was finally settled to the company’s advantage. Dunlop was replaced as warden in 1846. Early that year the tory ministry of William Henry Draper* and Denis-Benjamin Viger* cast about for a safe seat for Inspector General William Cayley*. Huron looked promising, and Dunlop was offered, as a sop, the superintendency of the Lachine Canal. To the shock and indignation of the opposition press, he accepted the post. He was thus to spend his last years at a distance from Huron County.

Again Dunlop shifted to relative obscurity, though in 1847 the Literary Garland published what is probably his best work, “Recollections of the American war.” A highly personal reminiscence of the war years, it is memorable above all for its vivid character sketches and, as always, a generous sense of humour. It was little remarked at the time of its publication, though the British Colonist drew attention to the “plain but pleasing and attractive style.” William Dunlop died the following summer near Montreal.

As surgeon, soldier, land agent, magistrate, militia colonel, politician, and member of numerous agricultural and literary organizations, Dunlop touched a great many of the central affairs of Upper Canadian life. Yet he is remembered above all for his engaging, witty, eccentric personality. Several people close to Dunlop have suggested that his comic persona was consciously created and maintained. In 1813 one of young Willy’s favourite aunts writes that his eldest brother, John, holds him in affection even though “he sees your follies and absurdities as every body must do for you hold them up to view as if they were accomplishments.” And in the novel Bogle Corbet; or, the emigrants, John Galt says of a character plainly based on Dunlop that he “had manifestly inherited from nature some excess of drollery, and conscious of this, had himself a vivid enjoyment in overcharging even to caricature his own eccentricities, in order to witness their effect on others.”

How is Dunlop’s eccentric character preserved? In part through his own writings. Both his longer prose works, Statistical sketches and “Recollections,” are highly subjective pieces with a distinctive authorial voice. His many letters to newspapers frequently advertise his character, and his caustic last will and testament (including “I give my silver cup, with a sovereign in it, to my sister Janet Graham Dunlop, because she is an old maid and pious and therefore will necessarily take to horning”) has been reprinted so often as to have become something of a cliché. Moreover, a great many of the people Dunlop knew could not resist trying to preserve him in print: in Britain his literary cronies, especially John Wilson and William Maginn; in Upper Canada John Mactaggart*, Samuel Strickland*, Sir James Edward Alexander, and, of course, Galt, among others; finally, and above all, Robina and Kathleen Macfarlane Lizars (granddaughters of Dunlop’s friend Daniel Horne Lizars), who published in 1896 a work called In the days of the Canada Company, an informal history of Huron County, of which Dunlop is the undisputed comic hero. But even before this publication, Dunlop had become something of a local folk hero. In the 1930s one Huron old-timer remembered hearing from his father a version of one of the best-known tales, and another said of the Lizarses’ stories that he had “heard them from the lips of the old pioneers gathered about the fireside of a winter’s night.”

Dunlop’s engaging character is thus his most substantial and lasting creation. What is the essence of that character? He was a wit, a storyteller, a great drinker, and a practical joker. Most of the remembered stories cannot be verified or documented: they bear the truth of fiction, or of legend.

Dunlop is said to have done everything on a grand scale, and this is nowhere more evident than in his drinking. He kept his liquor in a wheeled, wooden cabinet called “The Twelve Apostles.” One bottle he kept full of water: he called it, naturally, “Judas.” His reputation as a maker of punch “and other antifogmaticks” was legendary with the Blackwoodians. Once in the Canadian legislature, when he spoke of travelling about on horseback with nothing but a sack of oatmeal, some honourable members shouted, “And a horn!” Even Susanna Moodie [Strickland*] (who did not meet Dunlop) tells a story of his drinking, in which Dunlop is inadvertently served a glass of salted holy water in place of Edinburgh ale. Dunlop’s consumption of snuff, which he kept in an immense box he called “the coffin,” was also typical of his gargantuan appetites. An unsympathetic legislative reporter once described him as “pulling out his half-bushel snuff box and chuckling like a clown in a circus company.” And, when an American border inspector doubted that the quantity of snuff he was carrying could be simply for personal use, Dunlop tossed a handful into the air and snorted it up as it fell about him, saying, “There, that’s what I want it for; that’s the way I use it.”

Like an unrestrained, oversized schoolboy, Dunlop delighted in shocking people. One afternoon in a store in Goderich, he directed each newcomer to fetch him some nails from a barrel – in which Samuel Strickland had dumped a live porcupine. He treated one unhappy Canada Company official to a ride through a gauntlet of howling wolves (simulated by Strickland and himself) until the fellow was thrown from his horse, and then nursed him back to health with soft words and alcohol. And he delighted in dressing the part of the uncouth backwoodsman, and then surprising onlookers with a learned monologue.

There is a strong element of teasing in the story of how his brother Robert came to wed their housekeeper, Louisa McColl, after losing a coin toss to William’s two-headed coin. Yet William was not always the winner in his own stories, as in the tale of the ship he piloted on to the rocks in Lake Huron (he called her “the Dismal”), or the story in “Recollections” of the commanding officer who repaid one of Dunlop’s blunders by smacking him smartly on the head with a switch and telling him he had been shot.

There is, of course, wit as well as slapstick in the Dunlop stories. Once, travelling in the bush with a logging chain wrapped about himself, he met an old friend from Scotland. When they parted, Dunlop asked the fellow to tell his friends at home that he had been found “in chains but well and happy.” At a public meeting in Goderich in 1840, he offered those assembled three good reasons for not going to church: “First that [a man] should be sure to find his wife there, secondly, he could not bear any meeting where one man engrossed the whole of the conversation, and thirdly, that he never liked singing without drinking.” And once, in the assembly, a fellow member interrupted him as he spoke on the subject of taxation to ask him how he would like a tax on bachelors. “Admirably,” he replied, “luxury is always a legitimate object of taxation.”

Dunlop was known under a variety of names, but the one that has lasted is Tiger. In Upper Canada he was also The Doctor, occasionally Peter Poundtext or Ursa Major, and often A Backwoodsman. More than the cairn that stands in his memory at the mouth of the Maitland River, the character of the backwoods savage/sophisticate which he created is his monument.

The most complete list of William Dunlop’s publications may be found in D. G. Draper, “Tiger: a study of the legend of William Dunlop” (phd thesis, Univ. of Western Ont., London, 1978). A select bibliography of his major Canadian works follows.

Dunlop’s guide for emigrants, Statistical sketches of Upper Canada, for the use of emigrants: by a backwoodsman, was sufficiently popular to require three editions. The first two were published in London in 1832; the second is identical to the first except for the title-page notation “A New Edition”; the third, issued in London the following year, includes a delightful preface which does not appear elsewhere. Shortly afterwards the Sketches were reproduced in whole or in part in a number of Canadian newspapers, including the Canadian Emigrant, and Western District Commercial and General Advertiser (Sandwich [Windsor, Ont.]), the Canadian Freeman, and the Montreal Gazette. A modern edition, based on the 1832 texts, appears in Tiger Dunlop’s Upper Canada . . . , ed. C. F. Klinck (Toronto, 1967), 63–137. His “Recollections of the American war,” originally published in the Literary Garland, new ser., 5 (1847): 263–70, 315–21, 352–62, 493–96, subsequently reappeared as Recollections of the American war, 1812–14 . . . , ed. A. H. U. Colquhoun (Toronto, 1905), and in Tiger Dunlop’s Upper Canada, 1–62. A copy of the pamphlet Defence of the Canada Company, by Dr. Dunlop, M.P.P., privately issued from Gairbraid in 1836, is at the AO.

AO, Canada Company records. PAC, MG 24, I46. PRO, CO 42, esp. 42/396. Can., Prov. of, Legislative Assembly, App. to the journals, 1841, app.TT. The Dunlop papers . . . , ed. J. G. Dunlop (3v., Frome, Eng., and London, 1932–55). John Galt, The autobiography of John Galt (2v., London, 1833); Bogle Corbet; or, the emigrants (3v., London, [1831]). [Samuel] Strickland, Twenty-seven years in Canada West; or, the experience of an early settler, ed. Agnes Strickland (2v., London, 1853; repr. Edmonton, 1970). [Susanna Strickland] Moodie, Life in the clearings versus the bush (London, 1853). Albion (New York), 1828–48. British Colonist, 1838–48. Canadian Emigrant, and Western District Commercial and General Advertiser, 1831–36. Canadian Freeman, 1827–34. Chronicle and Gazette, 1833–45. Colonial Advocate, 1826–34. Gore Gazette, and Ancaster, Hamilton, Dundas and Flamborough Advertiser (Ancaster, [Ont.]), 1827–29. Kingston Chronicle, 1826–33. Montreal Gazette, 1826–28, 1830–32, 1841–48. Toronto Patriot, 1832–44. Western Herald, and Farmers’ Magazine (Sandwich), 1838–42. W. H. Graham, The Tiger of Canada West (Toronto and Vancouver, 1962). R. D. Hall, “The Canada Company, 1826–1843”

Cite This Article

Gary Draper and Roger Hall, “DUNLOP, WILLIAM, known as Tiger Dunlop,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 7, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 14, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/dunlop_william_7E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/dunlop_william_7E.html |

| Author of Article: | Gary Draper and Roger Hall |

| Title of Article: | DUNLOP, WILLIAM, known as Tiger Dunlop |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 7 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1988 |

| Year of revision: | 1988 |

| Access Date: | December 14, 2025 |