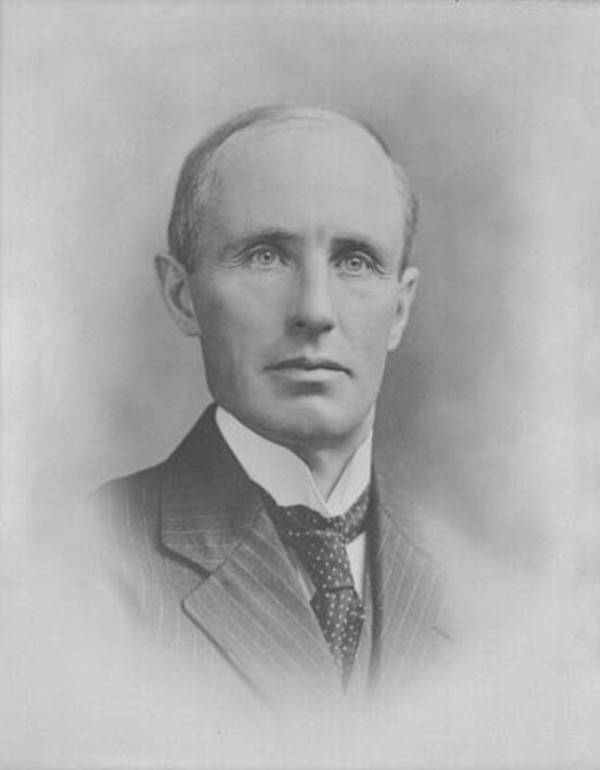

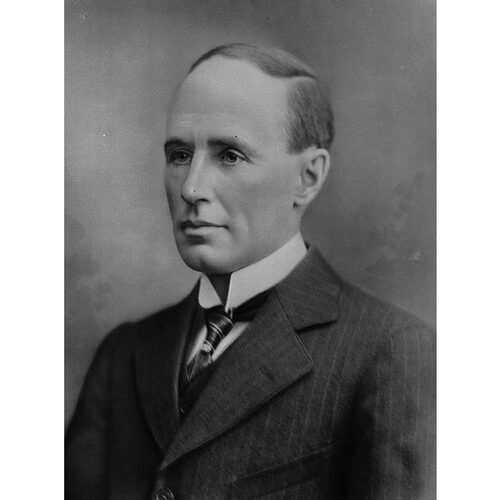

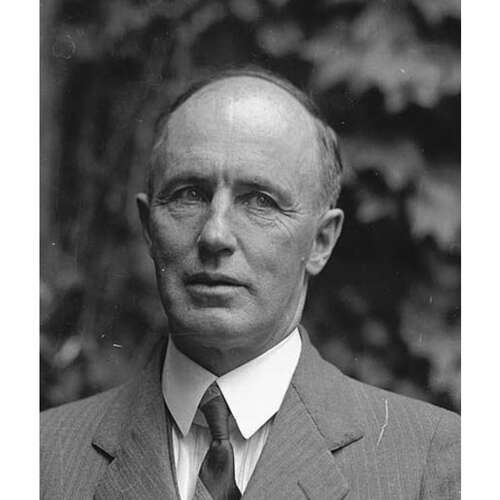

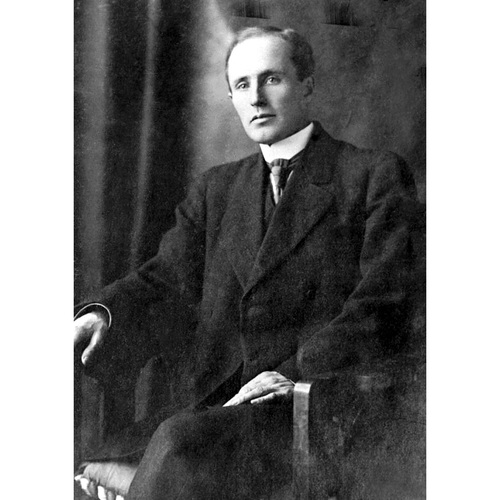

MEIGHEN, ARTHUR, teacher, lawyer, politician, businessman, and office holder; b. 16 June 1874 near Anderson, Ont., second child and eldest son of Joseph Meighen and Mary Jane Bell; m. 24 June 1904 Jessie Isabel Cox in Birtle, Man., and they had two sons and a daughter; d. 5 Aug. 1960 in Toronto and was buried in St Marys, Ont.

Arthur Meighen’s paternal grandfather, Gordon, was a Presbyterian Ulsterman who left Londonderry (Northern Ireland) in 1839 for Upper Canada. Five years later he acquired a farm lot in the southwest part of the province, near St Marys, where he became the local schoolmaster. At his death in 1859 his 13-year-old son, Joseph, left school to run the farm. Marriage in 1871 and six children followed in orderly progression. The oldest boy, Arthur, showed more aptitude for book learning than farm work. Accordingly, his parents moved to the outskirts of St Marys so he could attend high school without the expense of boarding. Arthur did his share of chores on the family’s dairy farm; at the same time he read voraciously, maintained first-class honours, and took part in the debating activities of the school’s Literary Society. His home environment, he later recollected, instilled in him “the immeasurable value of sound education and the equally limitless and permanent importance of habits of industry and thrift.” Upon graduation in 1892, he enrolled at the University of Toronto, majoring in mathematics. Unlike his more worldly contemporary William Lyon Mackenzie King*, Meighen did not cut a broad swath on campus, limiting his scope to his courses, wide reading in English, history, and science, and enthusiastic participation in the mock parliament. In 1896 he received his ba with honours in mathematics; the next year he returned to Toronto to earn teaching qualifications at the Ontario Normal College.

Having obtained an interim specialist’s certificate, Meighen was hired in 1897 by the high school board of Caledonia, east of Brantford, to teach mathematics, English, and commercial subjects. The year started well, but by spring he had become embroiled in a bitter dispute with the chairman of the board, who resented his strict discipline of his daughter. Meighen resigned and moved west to Manitoba, where he found work heading the commercial department of the Winnipeg Business College. In the summer of 1899 he applied unsuccessfully for the post of principal at a high school in Lethbridge (Alta). In January 1900 the transplanted Ontarian commenced legal studies and was articled in a Winnipeg firm; by 1902 he was attached to a small law office in Portage la Prairie. On 2 Feb. 1903 he was called to the bar of Manitoba. He set up his own practice in Portage la Prairie, where he handled a mix of business, including wills, estates, real estate transactions, and minor criminal cases. About this time he met Isabel Cox from Granby, Que., who was then a schoolteacher in Birtle, and they married in June 1904. While Meighen built up his practice, he dabbled in the hot real-estate market, joined the Young Men’s Conservative Club, and in 1904 was an enthusiastic worker in the unsuccessful campaign of the local Tory mp, Nathaniel Boyd.

In the federal election four years later, Meighen himself carried the Conservative colours in Portage la Prairie. His nomination was uncontested, it being assumed that the Liberal incumbent, John Crawford, was a lock to hold the constituency. Meighen jumped into the campaign with vigour, travelling to the four corners of the riding by wagon or buggy. He proved to be an effective speaker. His opponent anticipated an easy ride on the coat-tails of Prime Minister Sir Wilfrid Laurier*. On polling day, 26 Oct. 1908, Meighen won by a narrow margin of 250 votes and he went to Ottawa, where he sat in the backbenches of the opposition led by Robert Laird Borden*. He made but two brief speeches in his first session of parliament, though they did catch Borden’s attention, and scarcely more in 1910. His one significant oration that year, in connection with a proposed railway investigation, even earned the praise of Laurier, who remarked to a colleague, “Borden has found a man at last.” In 1911 Meighen burnished his credentials as a progressive prairie Conservative with speeches advocating a reduction in tariffs on farm implements and stricter limits on business trusts. He took no part in the Conservatives’ obstruction in 1911 of Laurier’s reciprocity bill, but he campaigned hard for his party’s traditional National Policy of protection in the general election in September. Nationally, Borden led his Conservative forces to victory; in Portage la Prairie, Meighen upped his winning margin to 675 votes.

He was not, nor did he expect to be, appointed to the new cabinet as a representative of Manitoba. Dr William James Roche*, the mp for Marquette since 1896, and Robert Rogers*, the master of the province’s Conservative machine and a member of Premier Rodmond Palen Roblin*’s cabinet, stood ahead of him, and both became ministers. Meighen’s growing command of parliamentary procedure soon found an outlet, however. When the Liberals held up the government’s Naval Aid Bill, Borden turned to his young Manitoba protégé to find a way out. Meighen urged the adoption of a form of closure that was already operating in the British parliament, and suggested an ingenious ploy by which the rule could be implemented in the Canadian House of Commons without sparking an even more protracted debate. Borden introduced the motion for closure on 9 April 1913; although the enraged Liberals fought it tooth and nail, their efforts were in vain. Closure was passed after two weeks of heated debate, followed three weeks later by the bill (which was defeated in the Senate). Meighen’s role behind the scenes soon became known, for it was he who explained the procedural details in the commons. Opposition mps mockingly saluted him as the “Arthur” of the rule. Borden too was impressed. On 26 June Meighen was sworn in to the vacant position of solicitor general, which was then not part of cabinet.

While still a backbencher Meighen had acquired a reputation as a progressive Conservative. Just prior to his appointment, he, Richard Bedford Bennett*, William Folger Nickle, and others had voted against amendments to the Bank Act that they considered harmful to prairie farmers. In his new post, Meighen found himself defending the government from his erstwhile maverick allies. Borden assigned him the task of negotiating a financial arrangement with the Canadian Northern Railway, which was teetering on the edge of bankruptcy and threatening to bring down several provincial governments and a major chartered bank with it. After several weeks of investigation and hard bargaining, Meighen and his small team of government officials presented the cabinet with a proposal: a $45 million government guarantee of Canadian Northern bonds in return for a mortgage and a significant share of common stock. The cabinet was pleased, and Meighen was asked to pilot the resulting bill through the commons. Here, in May 1914, he encountered his fiercest opposition from his fellow western Tory, Bennett, who branded him “the gram[o]phone” of Sir William Mackenzie* and Sir Donald Mann*, the entrepreneurs who had created the Canadian Northern. The bill nonetheless became law, and Meighen continued to impress Borden as a troubleshooter. On 2 Oct. 1915 the prime minister would elevate his solicitor general to cabinet rank.

Canada entered World War I united, in parliament and across the country, but the unity did not last. By 1915 partisan divisions were apparent. Chief among the contentious issues were the conduct of the war, continuing railway deficits, and the lingering question of French-language schooling. In 1912 the Ontario government under Sir James Pliny Whitney* had imposed Regulation 17, which severely limited the scope of French as a language of instruction. By 1915 this issue was poisoning federal politics, pitting English against French and draining Quebec support for the war. The government preferred to leave the matter alone – it involved provincial jurisdiction – but in April 1916 three cabinet members from Quebec, Thomas Chase-Casgrain*, Esioff-Léon Patenaude*, and Pierre-Édouard Blondin*, urged Borden to refer it to the King’s Privy Council in Britain. No such action was taken. Feelings in Quebec remained strong and influential politicians there may have known of Meighen’s role in drafting Borden’s refusal. Meanwhile, military casualties in a war of attrition were threatening the viability of Borden’s commitment in 1916 that Canada would field half a million men. Meighen favoured a selective draft, and the prime minister came to support conscription after a tour of the Western Front. Meighen was given the job of drafting the Military Service Bill, which Borden introduced in June 1917, and then shepherding it through parliament. He performed brilliantly, even clashing with the revered Laurier. “We must not be afraid to lead,” the Manitoba mp declared. Victory in the commons blinded him to Patenaude’s prediction that conscription would “kill . . . the party for 25 years” in Quebec.

The government’s solution to the crisis over railway finance was, first, to appoint a commission of inquiry and, second, to use its ambiguous report as justification for nationalizing the Canadian Northern. The Liberals, who opposed the nationalization bill strenuously, charged the Conservatives with compensating shareholders for worthless stock, as a political payoff. Sir William Thomas White, the finance minister, led the government forces in the debate, but Meighen was prominent in fending off opposition charges of cronyism and corruption. The solicitor general took the lead in navigating an even more controversial bill through the commons in September 1917. The War-time Elections Bill was a highly partisan measure, branded a cynical gerrymander by the Liberals and defended as a noble act of patriotism by the Conservatives. This measure disenfranchised citizens of enemy alien birth who had been naturalized since 1902; at the same time it enfranchised the immediate female relatives – wives, widows, mothers, sisters, and daughters – of Canadian servicemen overseas. At one stroke, thousands of probable Liberal voters were removed from the rolls and replaced by women likely to vote Conservative. “War service should be the basis of war franchise,” Meighen declared in parliament. It was not the principle of the partial franchise for women but rather the reality of votes for the government that motivated him. He would take no part in the Borden government’s extension of voting rights to all females in 1918.

Borden led a Conservative government committed to a maximum war effort, but also a party whose electoral fortunes appeared grim, based on the results of recent provincial elections. The Military Service Act not only promised a solution to lagging military enlistment, it also split the opposition, with most English-speaking Liberals favouring conscription and francophone Quebecers rallying around Laurier, who stood opposed. Partisan Tories such as Robert Rogers urged a quick election, but Borden feared two things: national disunity and Laurier’s campaign magic. All through the summer of 1917, with much tense negotiation, Borden had sought a coalition with pro-conscription Liberals. Meighen was by this time one of his closest confidants. Borden made him secretary of state and minister of mines in August, and Meighen and cabinet colleague John Dowsley Reid* worked closely with the prime minister on the make-up of the Union government formed in October. Both Meighen and Reid were firm on Borden continuing as leader. Meighen moved to Interior, traditionally the key western portfolio, but his status was somewhat diminished as a result of the prime minister’s inclusion of three prominent western Liberals: Arthur Lewis Watkins Sifton*, Thomas Alexander Crerar*, and James Alexander Calder. Meighen gained from the exclusion of his Tory rival, Rogers, but he had to share administrative and political influence with immigration minister Calder. The alternative, an anti-conscription Liberal win in the election called for December, would be worse, he decided.

Initially leery of Calder, the master of the Saskatchewan Liberal machine, Meighen was assigned by Borden to work with him to organize the Union government’s campaign in the four western provinces. Meighen took charge of Manitoba, Calder had Saskatchewan, and Alberta was left to Sifton. In British Columbia, Calder saw to the organization while Meighen supplied the oratory. The two kicked off the Unionist campaign at Winnipeg on 22 October; they shared the platform with Crerar, whose background as president of the United Grain Growers was used to solidify farm support. Meighen quoted statistics to show that voluntary enlistments had fallen far below the Canadian Expeditionary Force’s casualty rate. The three heavyweights reprised their pitch for bipartisan support the next night in Regina. Meighen shared several platforms with the Liberal premier of Manitoba, Tobias Crawford Norris*. He barely needed to lift a finger in his own riding of Portage la Prairie, where a farmers candidate stepped aside so he could easily defeat F. Shirtliff. On election night, Meighen was in Vancouver. “The conscience of the nation triumphed,” he declared confidently at news of the Union government’s victory. He gave little thought to one ominous development: the total absence of Unionist mps from Quebec, which had voted overwhelmingly Liberal.

Borden decided to focus on two priorities: a full war effort and preparations for post-war demobilization. He had already established, in October, a coordinating committee of cabinet for each area; Meighen sat on the reconstruction and development committee. In May 1918, Borden brought Meighen and Calder with him to England to attend the Imperial War Conference, where matters of demobilization, reconstruction, and immigration were slated for discussion. Even in wartime, there was a full schedule of pomp and circumstance. Meighen found time to meet Canadian troops at the front, and at a meeting of the Royal Geographical Society he proclaimed that “Canada is British – never more British than now.” His main job in England, however, was to strike a deal with the Grand Trunk Railway, by which its assets would be brought into a national transcontinental system that included the Canadian Northern. No great fan of public ownership, he nonetheless believed there was no alternative. The head of the Grand Trunk, Alfred Waldron Smithers, held out for better terms, but within a year the Grand Trunk Pacific went into receivership. Meighen concluded the final negotiations in Ottawa in October 1919 and then piloted the Grand Trunk Railway acquisition bill through parliament.

Following the Allied victory in Europe, the government had turned its attention to the demobilization of half a million Canadian troops. Meighen oversaw one of the government’s main initiatives: a program to assist financially those veterans who wished to become farmers. This measure received all-party support, but another of Meighen’s high-profile actions did not. When a labour dispute in Winnipeg in May 1919 [see Mike Sokolowiski*] escalated to a general strike involving more than 30,000 workers, including sympathetic postal employees, Meighen and labour minister Gideon Decker Robertson* were dispatched to the west. Their immediate objective was to restart the postal system. On 25 May an ultimatum was issued to the sympathy strikers: return to work or lose your jobs. The majority of postal workers rejected the ultimatum though, with the hiring of new workers, deliveries soon resumed. Meighen held no brief for the strikers, most of whom he considered “revolutionists” intent on overthrowing duly constituted authority. He approved the arrest of the strike leaders, and urged that any foreign-born among them be summarily deported. Shortly after the strike ended, he brought forth amendments to the Criminal Code, collectively known as section 98, to ban association with organizations deemed seditious. This section effectively inverted the normal presumption of innocence. Meighen was unrepentant; for him, preserving “the foundation of law and order” took precedence.

The government’s aggressive stance at Winnipeg earned it the enmity of the more radical union members in Canada, one more addition to the growing list of groups with a grudge against it. The list included French Canadians angered over conscription, farmers irked by tariffs, Montreal businessmen alienated by railway nationalization, and citizens disenfranchised by the War-time Elections Act. Meighen was among those in cabinet who favoured a vigorous program of organization and propaganda to firm up a new unionist party that would cement the ties so recently formed between the Liberal and Conservative supporters of the coalition government. Preoccupied with national and international affairs of state, Borden deferred action on party matters until his health gave out. In early July 1920 he announced his intention to resign. Press rumours mentioned Meighen and the wartime minister of finance, Thomas White, as his likeliest successors. The caucus authorized Borden to choose. After input from over 100 mps, he ascertained that Meighen was the backbenchers’ favourite, while White was preferred by the ministers. Borden first approached White, who declined, and then he anointed Meighen. The new government took office on 10 July under the name of the National Liberal and Conservative Party.

As prime minister, Meighen faced a new opposition leader. Laurier had died in 1919 and been replaced at a Liberal convention by Mackenzie King. There were several parallels in the lives and careers of the two leaders. Both had been born in 1874 in southern Ontario and raised in Presbyterian homes. Both were undergraduates at the University of Toronto in the 1890s. Meighen went west and became a lawyer, while King pursued postgraduate studies. Their paths linked up again in 1908, when each was sent to the House of Commons, but whereas Meighen was re-elected in 1911 and 1917 and rose through Conservative and Unionist ranks, King was defeated both times. Having stood by Laurier, his reward was solid Quebec support in the Liberal leadership race. For his role in shaping the Military Service Act and the Union government, Meighen was vilified by Conservatives in Quebec, who had favoured White. On the personal level, the leaders provided a study in contrast. Meighen was a dogged logician and orator who believed in straight talk. His opponent was given to wordy platitudes and endless consultations. Their temperaments clashed, and so did their ambitions.

Meighen’s first priority was to pull together a functioning party organization behind his government. The Unionist caucus meeting in July, besides choosing a leader and a name, had also hammered together a platform. Key planks included support for a moderately protective tariff, opposition to class-based or sectional appeals harmful to national unity, and firm support for the British connection, accompanied by full Canadian autonomy. By this time, several prominent Liberal Unionists had retired from the cabinet, but the government continued to rely on the voting support of 25 to 30 Liberal Unionist backbenchers. Meighen’s challenge was to build a fighting force out of disparate elements. Such traditional Tories as Robert Rogers openly advocated a return to pre-war party lines, but Meighen refused to drop his new allies. Proud of the Union government’s record, he was committed to broadening the base of the old Conservative Party, much as John A. Macdonald* had done in 1854 and 1867 and Borden in 1911 and 1917. Accordingly, a national organizer (William John Black) was appointed in August 1920 and a publicity bureau was established. Meighen launched a countrywide speaking tour that summer and fall, accompanied through the western provinces by Calder, the ranking Liberal Unionist. The crowds were large and seemingly receptive. Less encouraging were his efforts to rejuvenate his party in Quebec. Its organization was weak and divided, and he himself was reviled as the architect of conscription.

In the commons Meighen faced not one but two new leaders. In addition to King, there was Thomas Crerar, the former Unionist minister of agriculture, who now headed a recently coalesced grouping of agrarian mps calling themselves the Progressive Party. This situation made for a highly competitive atmosphere during the 1921 session, though the government was able to sustain its position in key votes by margins of 20 to 30. In the debates over the throne speech and the budget, the Liberals challenged the government’s right to continue holding office in the face of by-election defeats, but Meighen held fast. With an eye to the upcoming election, he made moderate but consistent tariff protection his constant theme. Significant legislation included bills to ratify a trade treaty with France and to complete the takeover of the Grand Trunk Railway. The severity of the post-war recession increased public discontent, while paradoxically convincing the government of the need for budgetary retrenchment. In April a royal commission was established to investigate the grain trade, a partial response to farmers’ demands for the reinstitution of the post-war wheat board.

At the close of the session in June 1921, Meighen travelled with his wife to attend the Imperial Conference in London. Faced with the problem of reconciling the dominions’ growing autonomy with the need for a common imperial foreign policy, the British government had decided to convene a “Peace Cabinet” meeting for the purposes of informing and consulting the senior colonies. Although defence and constitutional adjustments were discussed, the chief topic proved to be the Anglo-Japanese alliance. For almost 20 years a pact of understanding and assistance had linked the two empires. Westminster, strongly supported by Australia and New Zealand, favoured the retention of the treaty. Meighen feared its renewal would alienate the United States. As early as February 1921, supported by a prescient memorandum from Loring Cheney Christie* of the Department of External Affairs, Meighen (its ex officio minister) had recommended to the British government the termination of the alliance, followed by an international conference of Pacific powers. Supported in London by Jan Christiaan Smuts of South Africa, he carried the day. At the ensuing Washington Conference on disarmament, the alliance was replaced by a multilateral agreement.

Despite this success, in August Meighen returned to a deteriorating political situation in Canada. The economy languished in recession. The accumulated resentments of four divisive wartime years had not abated. Voters with a grudge against the intrusive Union government awaited the next general election. A different leader might have evaded responsibility for the Borden record, but Arthur Meighen was not that kind of man. He was proud of the Conservative and Unionist achievements, to many of which he had personally contributed. If the ship of the National Liberal and Conservative Party were to go down, it would be with all guns blazing. Meighen renewed his call for the protectionist National Policy of Macdonald and Borden, and prepared to wage war against his Liberal and Progressive adversaries. “The one unpardonable sin in politics is lack of courage,” he had written to a supporter in 1920. “As a Government we are in an impregnable position, in point both of policy and of record, and I do not propose to make apology either by act [or] word.”

To face the electorate, Meighen needed first to reconstruct his cabinet. The government was especially vulnerable in Quebec and the prairies, precisely the areas of the country where promising ministerial recruits were scarce. The resounding western majorities of 1917 had melted away. Some Liberal Unionists had returned to King; others had followed Crerar into the Progressive Party. Arthur Sifton had died and in September 1921 James Calder left the cabinet for the Senate. Meighen did bring in his old backbench sparring partner, R. B. Bennett of Calgary, to be minister of justice, but Saskatchewan was left unrepresented. Prairie weakness in cabinet was mirrored at the constituency level; in many cases there was no organization at all for the government party. If anything, the situation was bleaker in Quebec, where traditional Bleus had had to share the spotlight with the nationalists in 1911, and had vanished in the disastrous conscription election of 1917. Meighen appointed four French Canadians in the reorganization of September 1921 but not one carried any weight with the public. His sincere attempts to recruit E.-L. Patenaude, who had resigned from Borden’s cabinet over conscription, were unsuccessful.

By the time Meighen had formally launched his campaign for re-election, with a major speech in London, Ont., on 1 September, political observers were unanimous. The National Liberal and Conservative Party was doomed to ignominious defeat in the contest set for December. Quebec was solidly Liberal and the Progressives were set to sweep the prairies. Ontario promised a three-way fight, with the Progressives benefiting from the friendly United Farmers government elected in 1919. Even the coastal regions seemed unpromising. Still, Meighen conceded nothing. For three months he stumped the country, travelling by rail, automobile, and boat to deliver some 250 speeches. He preached tariff protection in the west, defended conscription in Quebec, and championed public ownership of railways in the heart of Montreal, where the press, the Canadian Pacific Railway, and the Bank of Montreal were all bitterly hostile towards him. Although he lacked female candidates – few women ran altogether and only one, Agnes Campbell Macphail, a Progressive, was elected – Meighen appealed to the million-plus female voters, reminding them it was the Union government that had legislated votes for all women. He denounced King’s ambiguity on the tariff and railway issues, and attacked the class basis of the Progressives. Hecklers he handled with ease, and everywhere the crowds cheered. Even L’Action catholique (Québec), which opposed the government, conceded on 9 November that he was “a man of intellect and a leader.” The campaign was a personal triumph, but voting day was a disaster.

The National Liberal and Conservative Party was reduced to 50 seats, representing just three provinces (Ontario, New Brunswick, and British Columbia) and the Yukon. Meighen and nine cabinet colleagues were defeated in their own ridings. The Liberals, with 116 mps, would form the new government, though they fell just short of a parliamentary majority. The Progressives, with 65 members, earned official opposition status but declined the role. Some of them hoped to ally themselves with a reformed Liberal Party; others rejected party government on principle. Meighen moved quickly to position himself to face King’s minority government and exploit the ambivalence among the Progressives. While King deliberated over cabinet selections, Meighen arranged for his return in January 1922 in Grenville, a safe seat in eastern Ontario. When parliament convened in March, he was seated across from King, ready to do battle. Knowing that some in his party would blame him for the defeat, he had called a meeting of mps, senators, and defeated candidates just prior to the session. This meeting unanimously endorsed his leadership and officially reclaimed the traditional party name of Macdonald and Sir George-Étienne Cartier*: Liberal-Conservative. Thus fortified, Meighen undertook to undermine the new government and its sometime Progressive allies, while reviving his own party’s fortunes.

During the session of 1922 he reviewed King’s campaign promises, wondering aloud where the promised tariff reductions were. Meighen still favoured protection; he simply wished to place Liberal hypocrisy on the record. The major issue of the year blew up in September, long after parliament had recessed. A press release from the British government had invited the dominions to join it in defending the Dardanelles strait (Çanakkale Boğazi) from possible Turkish attack. The conflict was a leftover from the post-war peace settlement between the Allies and Ottoman Turkey. A new revolutionary government in Turkey had repudiated it and now threatened British troops. King, annoyed at the lack of consultation and alarmed at the potential for national and party disunity, played for time. Parliament would decide, but parliament was not in session. In a speech in Toronto on 22 September, Meighen publicly criticized the government’s inaction by quoting Laurier in 1914. “When Britain’s message came,” Meighen thundered, “then Canada should have said: ‘Ready, aye ready; we stand by you.’” His remarks went over well in Toronto, but poorly in Quebec and the prairies.

The Çanak crisis underscored a serious political dilemma: the incompatibility of some of Meighen’s deepest beliefs with the prevailing views of French-speaking Quebecers. On 9 July 1920 Henri Bourassa had condemned the new leader in Le Devoir (Montréal): “Mr. Meighen represents, in person and temperament, in his attitudes and his past declarations, the utmost that Anglo-Saxon jingoism has to offer that is most brutal, most exclusive, most anti-Canadian.” Through 1923 and 1924 there was little reason to think that Quebecers had changed their minds. The encouraging results of provincial elections and federal by-elections indicated clearly that the pendulum was swinging back to Meighen’s Tories in Ontario, British Columbia, and the Maritimes, but not in Quebec. The party could not even win a by-election fought on the tariff issue in September 1924 in the once Tory riding of St Antoine, in the heart of protectionist Montreal. The Liberals retained the seat and many, including the influential Montreal Daily Star and Gazette, blamed Meighen for the debacle.

Undaunted, in parliament and on the public platform the Conservative leader continued to stress tariff protection, which he coupled with the promise of freight rate adjustments to make the package more attractive to Maritime and prairie voters. King, encouraged by a decisive Liberal win in Saskatchewan in 1922 under Charles Avery Dunning, announced a federal election for 29 Oct. 1925. The prime minister asked for a mandate to deal with four issues: the railway deficit, immigration, the tariff question, and Senate reform. Meighen immediately placed King on the defensive by demanding what solutions the Liberals proposed and by reminding voters the government had done little in four years in office. The Progressives, now led by Manitoban Robert Forke*, were a much diminished force compared to 1921, and they limited their focus to the prairies. Aided by four newly elected provincial premiers, Meighen struck a solid chord all across English Canada. In Quebec he secretly delegated control of the Conservative effort to a former colleague from pre-conscription days, E.-L. Patenaude, who campaigned at the head of a slate of Quebec Conservatives loyal to the Macdonald-Cartier tradition, but independently of the controversial Meighen. Among those in Patenaude’s following was the prominent nationalist Armand La Vergne*.

The result was a stunning victory for the Conservatives, just seven seats short of a majority. In Ontario, the Maritimes, and British Columbia, they made a near sweep. Even on the prairies, where Meighen was returned in Portage la Prairie, they picked up ridings in Manitoba and urban Alberta. Quebec was a disappointment – just four anglophone Tory mps were returned – but Patenaude’s presence had doubled the Conservatives’ share of the popular vote. When King determined to carry on with Progressive support, despite losing his own seat, Meighen decided on a bold move to win back needed Quebec support. The death of the Liberal mp for Bagot opened a by-election there in December. The Conservative candidate was Guillaume-André Fauteux, one of Meighen’s francophone ministers from 1921. To boost his candidacy, Meighen announced a dramatic shift in policy. In the event of a future war, his government would seek electoral endorsement before sending troops overseas. The venue for his speech was not Bagot, but Hamilton, Ont., though he repeated the pledge in person and in French while campaigning for Fauteux. Unfortunately, the gambit was not only insufficient to win Bagot, it also upset a number of imperialist Conservatives, notably Ontario premier George Howard Ferguson*.

Meighen nonetheless approached the parliamentary session of 1926 aggressively. The decisive round with his Liberal nemesis was about to begin. King sought to win the support of the Progressive and Labour mps with policy concessions, but Meighen intended to hold firm to the principles of Conservatism, confident that the Liberal government would stumble. He was ready to assume office immediately, and bent all his efforts to winning a no-confidence vote in the commons. If a new election was required, he did not doubt the outcome. Interestingly, both he and King faced whispers of insurrection, with R. B. Bennett, the Tory mp for Calgary West, and Liberal premier C. A. Dunning waiting in the wings. In the first few divisions of the session, the Liberals secured sufficient third-party support to establish their right to retain office. Promises to ease rural credit, investigate Maritime rights, and reform the tariff were secured respectively by legislation, a royal commission, and a tariff advisory board. Finance minister James Alexander Robb* presented a prosperity budget with tax cuts and a surplus. However, Progressive support splintered when a special commons committee reported flagrant abuses in the Department of Customs and Excise under Jacques Bureau*. A motion on this maladministration by Henry Herbert Stevens* in late June 1926 threatened to bring down the government.

To avoid censure, King decided that parliament should be dissolved and an election called. Governor General Lord Byng*, the thoroughly honourable soldier who had commanded the Canadian Corps in France, refused his request. A surprised King abruptly resigned, leaving the country without a government. When Byng offered Meighen the chance to form a ministry, he accepted, though not without misgivings. His brief administration (Canada’s shortest until the 1980s) would run from 29 June to 25 September. By the rules of the day, mps who accepted cabinet appointment had to resign their seats and seek re-election. In a session where divisions were routinely decided by a handful of votes, the resignation of a dozen frontbenchers would be self-defeating. As a temporary measure, Meighen decided upon the legal, though unusual, ploy of appointing acting ministers. To become prime minister, however, he could not avoid resigning his own seat. Leadership of the Conservative forces in the commons fell to less skilled hands. The new government survived three key votes, but a motion in July by J. A. Robb, questioning the constitutional validity of Meighen’s acting ministry, killed it. Citing dubious constitutional precedents, and alleging British interference, King persuaded a handful of Progressives, who only days earlier had voted to censure his government, to switch their allegiance. The Robb motion carried by a single vote, the decisive margin provided by a Progressive who broke his pairing agreement.

Meighen had no choice but to request a dissolution, and an election was set for 14 Sept. 1926. After one indecisive victory each, the rubber match between King and Meighen was finally under way. Both entered the campaign brimming with confidence. King felt sure the country would rally behind his clarion call to assert Canadian autonomy in the face of obvious collusion between a British-appointed governor general and the Tory party. Meighen was just as certain that Canadians would see through the Liberals’ constitutional hue and cry, and punish them for the customs scandal. This time he would have a respected Quebec lieutenant at his side. His Hamilton speech may have ruffled imperialist feathers in Ontario, but it persuaded E.-L. Patenaude to campaign openly as a Meighen Conservative. Meanwhile the Progressives, sensing their ebb, scrambled to save their seats by arranging saw-offs with the Liberals. King used Robb’s prosperity budget to good effect, and he turned the untimely death of former Liberal customs minister Georges-Henri Boivin to advantage with a symbolic pilgrimage to his grave. (Boivin, appointed to clean up the mess left by Bureau, had come under fire by the opposition.) When the votes were counted, it was King who emerged victorious. Quebec stood firm, and the Liberal-Progressive alliance produced victories in two dozen Ontario and Manitoba seats. Meighen lost his own riding.

And there it was. In the decisive battle, Arthur Meighen had come second best. He immediately tendered his resignation to the governor general, agreeing to stay on as prime minister until King had constructed a cabinet. Without a seat for the second time in five years, he decided to relinquish the party leadership as well. He summoned a special meeting in Ottawa of Conservative mps, senators, and defeated candidates on 11 October. They accepted his resignation, and selected Hugh Guthrie*, a prominent Unionist Liberal who had stayed with the Tories, as their parliamentary leader for the next year. At the same meeting a committee was struck to organize a leadership convention; for the venue it settled on Winnipeg in October 1927. Press speculation centred on Meighen and Ontario premier Howard Ferguson as the prime contenders, though each firmly denied any aspiration. When Meighen, from the convention platform, launched into an eloquent defence of his controversial Hamilton speech of 1925, Ferguson offered a spirited rebuttal. Most delegates cheered for Meighen and hooted at Ferguson, but the net result was the elimination of both from consideration. R. B. Bennett carried the convention on the second ballot.

Now in his early fifties, Meighen launched himself into a new career in the business world. It was not an entirely novel departure: years ago, in Portage la Prairie, he had branched out from law into land speculation and directorships in local companies. The business world intrigued him. Of the many offers that had come his way, he had accepted an invitation in 1926 to become a vice-president and general counsel for Canadian General Securities Limited, a Winnipeg investment brokerage firm that was looking to expand into Toronto. In November 1926 he moved with his wife and daughter to the Ontario capital – their two sons were then at university. The next September they purchased a home at 57 Castle Frank Crescent in the affluent Rosedale neighbourhood. For three years Canadian General Securities prospered, but the stock-market crash of 1929 nearly bankrupted it. Meighen suffered great anxiety, in particular because many modest investors had entrusted their funds to the company out of regard for him. Long hours and prudent management paid off and within two years the worst was over. He began to accept non-political speaking engagements in Toronto and as far away as Washington. He even took on a few legal cases. In June 1931 he was appointed to the Hydro-Electric Power Commission of Ontario on the recommendation of Ferguson’s successor as premier, George Stewart Henry.

Life in Toronto for the Meighens differed considerably from their years in Ottawa. Almost from the time he had entered Borden’s cabinet in 1915, politics and government had consumed his life. It was his wife, whom he affectionately called Nan in private, and more formally referred to as Mrs Meighen in public, who had largely raised their three children: Theodore Roosevelt O’Neil, Maxwell Charles Gordon, and Lillian Mary Laura. He was a loving but reserved father, given to delivering admonitions, to his sons in particular, on the virtues of thrift, perseverance, and hard work. He had never sought the social or ceremonial frills of public life, so he did not miss them when he left politics. His wife enjoyed social gatherings more than he did, but neither of them was in the least bit pretentious. In Toronto, he insisted on walking to work, a distance of some three miles from Rosedale to his Bay Street office. One advantage of his career change was that he found more time to indulge his lifelong interest in reading, as well as games of bridge and golf with close friends. And once the financial crisis of 1929 was overcome, he began to accumulate a substantial fortune from various astute investments. Meighen had largely missed his children’s formative years, but he was determined to provide for them and his future grandchildren whatever material support they might need as they made their own way into responsible adulthood. In the meantime, he was avoiding involvement in partisan politics. That part of his life, it seemed, was over.

Since the convention of 1927, R. B. Bennett had completely ignored him. Meighen was not asked to help in the slightest way during the victorious Conservative campaign of 1930. The obvious snub wounded a proud man. When at last an offer came to head the federal Board of Railway Commissioners, Meighen declined, but he did not refuse Bennett’s next proposal: appointment to the Senate and the position of government leader there. Meighen accepted, effective 3 Feb. 1932, on condition that he would be expected in Ottawa only while the Senate was sitting. Though technically a member of cabinet as a minister without portfolio, he did not attend meetings on a regular basis. One of his first responsibilities was to press the Conservative case in the consideration of three Liberal senators implicated in the Beauharnois Scandal. Meighen was at his eloquent best in the climactic debate, though he took little pleasure in the outcome: censure of senators Wilfrid Laurier McDougald* and Andrew Haydon. He was more at home in expediting the refinement of complex pieces of legislation. For example, in 1932 he introduced the Canadian National-Canadian Pacific Bill, to facilitate the coordination of the railways’ operations, before it moved through the commons.

Meighen was himself the target of conflict-of-interest allegations by Ontario’s Liberals, who charged that trust funds he administered had benefited from decisions made by the Hydro-Electric Power Commission, on which he sat. The newly elected government of Mitchell Frederick Hepburn established an inquiry in 1934 to investigate the charges, but its report was inconclusive and the issue died down. The country’s attention shifted to Ottawa when Bennett, in a series of five nationwide radio broadcasts early in 1935, denounced the old order and advocated fundamental reforms, a Canadian version of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal in the United States. Meighen was not impressed by the prime minister’s radical oratory, but as chief lieutenant in the upper house, he loyally shepherded the reform legislation through the Red Chamber. Typically, the Senate would make a series of amendments to each bill, numbering 51 in the case of the Employment and Social Insurance Act. At the end of the session Meighen was satisfied with the result. Later, in the presence of Bennett himself, he would denounce “not the legislation, which was enlightened, but the [radio] speeches, which frightened.” Despite their parliamentary collaboration, Meighen declined Bennett’s request to campaign in the election of 1935. He still remembered the snub of 1930.

As the two Tory titans watched their common foe, King, comfortably take back power, they finally discarded their old animosities. Meighen in the Senate and Bennett in the commons were still Canada’s outstanding Conservative parliamentarians. When Bennett decided in March 1938 that his health would not permit him to carry on, he hoped Meighen would be his successor. The latter had no desire to reassume the leadership – it was clear to him that the west and Quebec would not accept him – but he did share Bennett’s misgivings about the apparent front runner, Robert James Manion*. Though defeated in his riding in 1935, “Fighting Bob” had parlayed marriage to a French Canadian woman and his congenial personality into a formidable candidacy. Meighen tested the waters for Sidney Earle Smith, president of the University of Manitoba, but there was little interest, even in Winnipeg. When Bennett asked Meighen to give the keynote address to the national party convention in July 1938 and suggested Commonwealth defence as a topic, he readily agreed. With war threatening to break out in Europe, and Canada ill-prepared, it was a subject near to his heart. He delivered another barnburner reminiscent of his Winnipeg address of 1927, except this time Bennett and Ferguson applauded while the Quebec delegates sat on their hands, bitterly opposed to his call for Canadian-British solidarity. The convention confirmed the change of the party’s name, from Liberal-Conservative to National Conservative. On the leadership vote, Manion won on the second ballot, but neither Meighen nor Bennett was present to congratulate him.

Although Meighen sought to avoid open conflict with the new leader, he was singularly unimpressed with Manion’s performance. Where Meighen would have harassed the Liberals mercilessly for their tepid preparations for war, Manion simply echoed the government’s pledge to avoid conscription in any conflict. On the question of railway deficits, Meighen reversed his long-standing opposition to the amalgamation of the Canadian National Railways and the CPR, and supported a Senate motion that advocated unified management. This volte-face angered Manion, who was publicly opposed to such a step. When the 1940 election campaign began, Meighen stayed out of the fray, as he had in 1935. He was not surprised at the drubbing administered to his party by the Liberals, though he regarded the King ministry with barely concealed contempt. When some Conservatives urged him to leave the Senate and reassume the leadership, however, he declined. Manion, who had lost his own seat, was replaced by Richard Burpee Hanson* of New Brunswick, who provided competent if unexciting parliamentary direction. The stiffest opposition criticism still came from Meighen, whose public and Senate speeches deplored government hypocrisy and inaction on preparations for war. “I cannot agree that we are doing our part,” he thundered in the Senate on 13 Nov. 1940.

Sensing the growing demand that he take the Conservative helm, in 1941 Meighen approached John Bracken*, the Liberal-Progressive premier of Manitoba, to see if he could be persuaded to come to Ottawa and take on the job. Though flattered, Bracken remained on the sidelines as the pressure on Meighen mounted. He despised King and despaired of ever seeing the Liberals mobilize a full war effort, but he still resisted the call, feeling himself too old at 68 to accept the challenge. King certainly did not want him back in the commons. Meighen’s debating skills and grasp of administrative detail and parliamentary procedure were exceptional. King understandably regarded the possibility of his old foe’s return with foreboding, as he revealed in his diary on 6 Nov. 1941: “I am getting past the time when I can fight in public with a man of Meighen’s type who is sarcastic, vitriolic and the meanest type of politician.” At a party meeting in Ottawa that month, Meighen launched another blistering assault on the Liberal government’s faltering war effort. Subsequently, the delegates voted by a margin of 37–13 to offer the vacant party leadership to Meighen. Citing the lack of unanimity and noting that the meeting was called for other purposes, he declined the honour. The delegates persisted and, in a subsequent motion, they unanimously requested that he accept. Reluctantly, Meighen agreed and he assumed control on 12 November, but on the condition that the Conservative Party would commit itself to “compulsory selective service over the whole field of war.” No longer would the party follow public opinion, as it had under Manion and Hanson. With Meighen back at the helm, the Conservatives would attempt to lead it.

Meighen could not forget his own two boys in uniform: Ted was in the Royal Canadian Artillery while Max served in the Royal Canadian Ordnance Corps. “I never knew what human longing was until separated by war from the sons I love so much,” he had written in March 1941. “I sit in my office just gazing on the folder with its two photos.” Such fatherly devotion gave a harder edge to his attacks on the Liberals. It was not just that he had warned of impending disaster through the 1930s. Now, his own kin were putting their lives on the line, yet the country was still not on a full war footing. Not surprisingly, he fought the by-election of 9 Feb. 1942 in York South on the issue of compulsory service. Occasioned by his need as party leader to obtain a seat – he had left the Senate on 19 January – the battle took on a decidedly nasty tone. The Co-operative Commonwealth Federation attacked him as yesterday’s man and a tool of big financial interests. Officially, the Liberals stayed out of the contest but most of their foot soldiers supported Joseph William Noseworthy, the CCF standard-bearer. King played his part by announcing a national plebiscite on the issue of conscription, thus spiking the Conservative guns. Moreover, the CCF, in an appeal to working-class voters, called not just for a full war effort but for social justice after the war. Meighen met humiliating defeat in a traditional Tory riding.

Meighen’s first instinct was to resign but he felt obligated to the party. Rather than contest another by-election, he allowed Hanson to continue as Conservative house leader. The arrangement did not work well. They clashed over tactics and policy. Meighen still believed Canada’s lacklustre war effort was the central issue, while Hanson emphasized social and economic reforms. A semi-official policy conference at Port Hope, Ont., in September 1942 developed a platform significantly more progressive in tone than Meighen would have preferred. It advocated the adjustment of farm debt, a national labour relations board, federal aid for low-cost housing, comprehensive social security, and a national contributory system of health care. Meighen was wary of the state providing such a range of social services, but his attention was directed elsewhere. On his initiative, an organizing committee was established that same month to arrange a leadership convention for December in Winnipeg. He worked relentlessly behind the scenes to persuade John Bracken to stand for the leadership, and he used his party contacts to advocate the Manitoba premier as the best choice to succeed him. Both Bracken and the party were reluctant, but Meighen prevailed. The party left Winnipeg with a new name (Progressive Conservative), a new leader (Bracken), and new policies (the Port Hope platform). As for Meighen, he informed the delegates he was retiring for good, leaving his words and deeds as leader “unrevised and unrepented.”

Inevitably, Bracken’s failure to defeat the weary Liberals in the election of 1945 reflected nearly as much on Meighen’s judgement as it did on Bracken’s modest gifts. Still, the Progressive Conservative Party was alive and would eventually triumph under another westerner, John George Diefenbaker*. Meighen took little part in politics after 1945. A collection of his major speeches going back to 1911 was published as Unrevised and unrepented . . . (Toronto, 1949). To his delight it garnered favourable reviews, even from Liberals. A few years later, a recording of one of those speeches, “The greatest Englishman of history,” was made into a vinyl LP and circulated to every Canadian university and every Ontario high school, courtesy of an anonymous benefactor. This speech, a tribute to William Shakespeare, had been first delivered in 1936. Meighen’s speech-making declined with his advancing years, as did his attention to his investment business in Toronto. He continued to enjoy reading, golf, bridge, and lunches at the Albany Club until well into his eighties. After a short illness, he died in his sleep on 5 Aug. 1960. He was given a state funeral in Toronto and then driven slowly across Ontario to St Marys, the town of his childhood years, for burial.

On any list of Canadian prime ministers ranked according to their achievements while in office, Arthur Meighen would not place very high. Taken together, his two stints as first minister total less than half a normal four-year term. In 1920–21 he was preoccupied with post-war reconstruction and a severe economic recession. Although his performance was competent, it was not exciting. Only at the imperial prime ministers’ conference did he shine, loyally but effectively prodding Britain to transform the Anglo-Japanese alliance into a multilateral agreement that properly included the United States. In 1926 he had time only to carry out the most necessary administrative functions, while fighting the ultimately decisive campaign against King’s Liberals. Therein lay the rub. In three contests between King and Meighen, the Grits won in 1921, the Tories placed first in 1925, but in the winner-take-all third match, he was beaten by his hated rival. This period in Canadian history became the Age of King, not the Age of Meighen. Tellingly, Meighen himself would not have accepted such an assessment as either fair or just. In our dominion, he stated in a farewell tribute to R. B. Bennett in January 1939, “there are times when no Prime Minister can be true to his trust to the nation he has sworn to serve, save at the temporary sacrifice of the party he is appointed to lead.” In the same speech he took aim at the indecisive ambiguity of their mutual foe, King. “Loyalty to the ballot box is not necessarily loyalty to the nation,” he pointedly declared. “Political captains in Canada must have courage to lead rather than servility to follow.”

Arthur Meighen had courage in abundance. His instinct was to confront an issue, an opponent, or a situation. Early in his career, he benefited from this quality. Utilizing his prodigious memory, crystal-clear logic, and gift for oratory, he rose rapidly through the Conservative ranks. Once he was face to face with a master tactician like King, however, his advance faltered. From Meighen’s perspective, the Liberal leader did not play fairly. He dodged issues, avoided accountability, and elevated hypocrisy to new heights. What Meighen could not see was that his own early successes as a minister in the Union government of Sir Robert Borden exacted a price on his later career. Before he even assumed prime ministerial office, he had seriously alienated French Canadians by advocating conscription, new Canadians by passing the War-time Elections Act, Montreal businessmen by nationalizing railways, labourers by suppressing the Winnipeg General Strike, and farmers by sticking to the protective tariff. Given his personality, he would not recant any of these policies. They would remain “unrevised and unrepented.”

The record must also show Meighen’s accomplishments, however. As a rising minister in the wartime government, he did much of Borden’s heavy lifting, particularly after 1915. As leader of the opposition in the 1920s, he rallied Conservative forces in the House of Commons, held a vacillating Liberal government accountable for a wretched customs scandal, and came close to reclaiming power. During the 1930s he served capably as Conservative leader in the Senate, and his speeches decrying isolationism helped to rally public opinion away from a dangerous neutralism. Late in his sixties, he heeded a party draft and did what he could to lead his beloved Conservatives back from oblivion. His final act was to hand over leadership of a renewed party to a competent, if not magnetic, successor. These achievements were not all that he set out to do in 1908, but his performance in politics was certainly well above average. His most fitting epitaph came from a bitter opponent, the Liberal Manitoba Free Press. Upon his first retirement, in 1926, its legendary editor, John Wesley Dafoe*, lamented Meighen’s loss to Canadian public life: “To fight his way to the charmed government ranks in six years; . . . to attain and hold against all comers the position of the first swordsman of Parliament – these are achievements which will survive the disaster of to-day.”

The most important primary source for this biography is the Arthur Meighen papers (MG 26, I) at Library and Arch. Canada (Ottawa). Other useful collections there include the papers of Sir Robert Borden (MG 26, H), John Bracken (MG 27, III, C16), C. H. Cahan (MG 27, III, B1), R. B. Hanson (MG 27, III, B22), W. L. M. King (MG 26, J), R. J. Manion (MG 27, III, B7), the Progressive Conservative Party of Canada (MG 28, IV 2), H. H. Stevens (MG 27, III, B9), and J. S. Woodsworth (MG 27, III, C7). The originals of the R. B. Bennett papers are in the Univ. of N.B. Library, Arch. and Special Coll. Dept. (Fredericton), and the Arch. of Ont. (Toronto) holds the G. H. Ferguson papers (F8).

Meighen published two books of his speeches: Oversea addresses: June–July 1921 (Toronto, 1921) and Unrevised and unrepented: debating speeches and others (Toronto, 1949). The published Debates (Ottawa) of the House of Commons, 1908–26, and the Senate, 1932–42, are the best sources for his parliamentary orations. Another period source not be overlooked is the Canadian annual rev. of public affairs (Toronto).

Any student of Meighen’s life and career will be indebted to the works of Roger Graham, whose magnum opus is Arthur Meighen: a biography (3v., Toronto, 1960–65). In addition, Graham edited a volume in the Issues in Canadian Hist. series, The King-Byng affair, 1926: a question of responsible government (Toronto, 1967), penned a Canadian Hist. Assoc. booklet, Arthur Meighen ([Ottawa], 1968), and contributed a fascinating analytical chapter, “Some political ideas of Arthur Meighen,” in The political ideas of the prime ministers of Canada, ed. Marcel Hamelin (Ottawa, 1969), 107–20. Graham’s approach is both scholarly and laudatory. His work needs to be read alongside the first two volumes, covering 1874–1932, of R. MacG. Dawson and H. B. Neatby, William Lyon Mackenzie King: a political biography (3v., Toronto, 1958–76).

The three relevant volumes of the Canadian Centenary Ser. are immensely useful: R. C. Brown and Ramsay Cook, Canada, 1896–1921: a nation transformed (Toronto, 1974); J. H. Thompson and Allen Seager, Canada, 1922–1939: decades of discord (Toronto, 1985); and Donald Creighton, The forked road: Canada, 1939–1957 (Toronto, 1976). Another three books provide helpful coverage of the Conservative Party: John English, The decline of politics: the Conservatives and the party system, 1901–20 (Toronto, 1977); L. A. Glassford, Reaction and reform: the politics of the Conservative Party under R. B. Bennett, 1927–1938 (Toronto, 1992); and J. L. Granatstein, The politics of survival: the Conservative Party of Canada, 1939–1945 ([Toronto], 1967). Other secondary sources of continuing value for key aspects of Meighen’s career include R. C. Brown, Robert Laird Borden: a biography (2v., Toronto, 1975–80), 2, J. M. Beck, Pendulum of power: Canada’s federal elections (Scarborough, Ont., 1968), W. L. Morton, The Progressive Party in Canada (Toronto, 1950), and Ramsay Cook, The politics of John W. Dafoe and the “Free Press” (Toronto and Buffalo, N.Y., 1963).

After Graham, the two biggest boosters of Arthur Meighen have been the Tory journalist Michael Grattan O’Leary* in his Recollections of people, press, and politics, foreword R. L. Stanfield (Toronto, 1977) and the CCF academic Eugene Alfred Forsey* in A life on the fringe: the memoirs of Eugene Forsey (Toronto, 1990). Not so complimentary was Liberal journalist William Bruce Hutchison* in Mr. Prime Minister, 1867–1964 (Don Mills, Ont., 1964), 189–201. Recent historical judgement continues to be severe, especially in Michael Bliss’s treatment of Meighen in Right honourable men: the descent of Canadian politics from Macdonald to Mulroney (Toronto, 1994) and J. L. Granatstein and Norman Hillmer’s assessment in Prime ministers: ranking Canada’s leaders (Toronto, 1999).

There are not many journal articles devoted to Meighen’s political career. He himself contributed one, “The Canadian Senate,” Queen’s Quarterly (Kingston, Ont.), 44 (1937): 152–63. Two notable works are by Roger Graham: “Arthur Meighen and the Conservative Party in Quebec: the election of 1925,” Canadian Hist. Rev. (Toronto), 36 (1955): 17–35 and “Meighen and the Montreal tycoons: railway policy in the election of 1921,” Canadian Hist. Assoc., Hist. Papers (Ottawa) (1957): 71–85. An early article by J. B. Brebner, “Canada, the Anglo-Japanese alliance and the Washington conference,” Political Science Quarterly (New York), 50 (1935): 45–58 describes Meighen’s pivotal role in reorienting British imperial policy towards Japan. L. A. Glassford outlines the impact of women voters on Meighen’s party in “‘The presence of so many ladies’: a study of the Conservative Party’s response to female suffrage in Canada, 1918–1939,” Atlantis (Halifax), 22 (1997–98), no.1: 19–30. Finally, J. L. Granatstein ably covers the electoral coup de grâce administered to Meighen by the voters in “The York South by-election of February 9, 1942: a turning point in Canadian politics,” Canadian Hist. Rev., 48 (1967): 142–58.

Cite This Article

Larry A. Glassford, “MEIGHEN, ARTHUR,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 18, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 20, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/meighen_arthur_18E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/meighen_arthur_18E.html |

| Author of Article: | Larry A. Glassford |

| Title of Article: | MEIGHEN, ARTHUR |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 18 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2005 |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | January 20, 2026 |