Source: Link

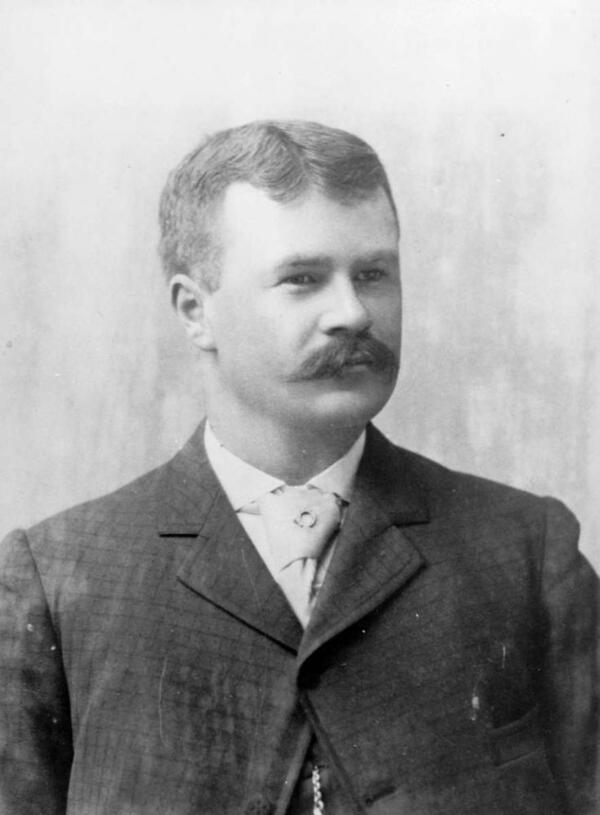

TOLMIE, SIMON FRASER, veterinarian, farmer, civil servant, and politician; b. 25 Jan. 1867 on Vancouver Island, son of William Fraser Tolmie* and Jane Work, and grandson of John Work*; m. 6 Feb. 1894 Mary Ann (Anne) Harrop in Victoria, and they had two sons and two daughters; d. 13 Oct. 1937 in Saanich, B.C.

Early life and education

The second youngest of 12 children, Simon Fraser Tolmie was born and raised at his family’s farm, Cloverdale, in the first stone house built on Vancouver Island. Cloverdale was located just north of Victoria, in an area that would become part of Saanich in 1906. His father, William Fraser Tolmie, was from Scotland, where he was educated as a physician and surgeon. As a medical officer in the service of the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC), William travelled to the Columbia River in 1833, settling in Victoria in 1859. He later rose to the position of chief factor for the HBC and established himself as a prominent breeder of cattle and other livestock. He also became engaged in the public life of the British colony, serving as a member of the House of Assembly of Vancouver Island and later the Legislative Assembly of British Columbia. Simon Fraser Tolmie’s mother, Jane Work, was also from an early immigrant family. Her father, John Work, came from Ireland and settled his family in Victoria in 1849. He later became chief trader for the HBC and a member of the Legislative Council of Vancouver Island. The marriage of William Fraser Tolmie and Jane Work represented the union of two prominent settler families, part of the HBC establishment and what Amor de Cosmos* would call the “family-company compact,” which had a major influence on the development of Vancouver Island and British Columbia.

Simon Fraser Tolmie grew up under the strict disciplinary influence of his mother, who passed away when he was 13 years old, and his father, who died six years later. Tolmie’s interests, like his father’s, gravitated towards the family farm, which would remain his home for almost his entire life. As a youngster at Victoria Collegiate School he was “a middling student” with “average grades,” according to his report cards. He later attended the Ontario Veterinary College in Toronto and was described by one of his teachers in a letter of recommendation as “an observing, careful and attentive student.” After completing his degree in veterinary medicine in 1891, he returned to Cloverdale, where he took up farming, raising prize cattle. He also established a private veterinary practice in Victoria and worked for the city inspecting ships that brought livestock to Vancouver Island. During this period, Tolmie also owned a farm in the interior of British Columbia, near Enderby in the Okanagan valley. In 1894 he married Mary Ann Harrop, who was known as Annie, with whom he would raise two sons and two daughters.

The civil servant

In addition to having a busy personal and professional life, Tolmie was drawn to public service. In 1900 he was appointed inspector of animals by the government of Canada, and the following year he was made assistant inspector of animals for the provincial government. He enjoyed this work, and in 1904 became the chief veterinary inspector of British Columbia. Two years later he resigned to become Canada’s chief veterinary inspector. As a senior civil servant, he was required to spend most of his time in Ottawa. He maintained his Victoria farm as an agricultural showplace but no longer managed it directly. Tolmie applied himself to public policy, writing reports and making speeches, most of which were focused on raising the standards of Canadian livestock. He was also involved in many veterinary and agricultural associations as well as social clubs.

Federal politics

While Tolmie came into contact with politicians and ministers, he did not appear to have the ambition to become an elected representative. He was a Conservative by inclination, however, and an ardent supporter of Sir Robert Laird Borden, leader of the federal Conservative Party. When Borden formed a national Union government in 1917, Tolmie was drafted, reluctantly, as the candidate in Victoria. He was easily elected and resigned from his position at the Department of Agriculture. On 2 Aug. 1919 Tolmie was appointed minister of agriculture. The following October he stood for re-election and was successful again. In July 1920, when Arthur Meighen* succeeded Borden as Conservative leader and prime minister, Tolmie continued as minister. Although he left most of the administrative details to his deputy minister, Tolmie’s tenure as minister was marked by the standardization of produce through grading and regulation, and by his lobbying in England in 1921 for the removal of the British embargo on Canadian cattle, which was lifted the following year.

A congenial, easygoing minister of agriculture, Tolmie was more of a technocrat than a political champion. He was described as the “head farmer of Canada” in historian Sydney Wayne Jackman’s Portraits of the premiers. With the defeat of the Meighen government in 1921, Tolmie was again re-elected, and served as an opposition mp and spokesman for the Conservatives on agricultural issues. He was seen as a competent local representative in Victoria and a loyal party man. As a result, he was appointed chief organizer for the party in 1923. These were dramatic years in Canadian politics, characterized by minority parliaments and instability, culminating in a constitutional crisis: the King–Byng affair of 1926 [see Julian Hedworth George Byng; William Lyon Mackenzie King*]. Tolmie retained his seat in parliament during these tumultuous times and the federal elections of 1925 and 1926, but he was relieved of his role as chief organizer when a new Conservative leader, Richard Bedford Bennett*, was chosen in late 1927.

British Columbia politics

Meanwhile, the Conservative Party in British Columbia was undergoing a period of disorganization and dissension. Partisan politics had been introduced in the province in 1903 with the election of a Conservative government led by Richard McBride*. Before that time, the provincial legislature had comprised unaffiliated elected members who coalesced around factions and personalities. By the mid 1920s the Conservative glory days of the McBride era were long gone, with Liberal administrations in office in Victoria since 1916. Partisanship in British Columbia was rambunctious and unpredictable, with some wishing to return to a time when parties and political patronage were less dominant.

The 1924 provincial election had resulted in a confusing political stalemate, with the Liberals barely holding on to power in Victoria as a minority government under long-time Premier John Oliver*. The opposition was divided between the Conservatives and the upstart Provincial Party formed by Sir Charles Hibbert Tupper* with the help of Alexander Duncan McRae*. The Conservatives had been led by William John Bowser for three consecutive general election losses; this time he was personally defeated in his own riding. The Provincial Party had emerged with support from Vancouver business leaders who were dissatisfied with British Columbia’s political leadership, calling loudly for an end to waste in government and advocating the abolition of the party system.

Although it had received almost a quarter of the ballots cast in the election, the Provincial Party did not have the organization or leadership to sustain itself. With Bowser’s defeat and resignation, the British Columbia Conservatives puzzled over their options as an opposition party. The legislative caucus reached out to Tolmie, offering him the leadership. He demurred, however, saying that his federal responsibilities would need to take priority. The provincial Conservatives drifted, appointing an interim leader, Robert Henry Pooley, until the situation would be clarified.

B.C. Conservative leader

Immediately following the 1926 federal election, the British Columbia Conservatives called a leadership convention. Scheduled for November in Kamloops, it surely ranks as one of the most bizarre leadership contests in the history of the province. On the eve of the event, former leader Bowser, a strong contender to reassume the post, withdrew from the race. An intensely polarizing figure, he seemed to recognize that his candidacy was harmful to the party. Bowser threw his support behind Senator James Davis Taylor, who squared off against Leon Johnson Ladner, a newcomer who seemed to represent the potential for renewal.

The convention was deeply deadlocked. After seven ballots, neither Taylor nor Ladner could achieve the necessary 60 per cent majority required for victory. In frustration, the candidates suggested offering the leadership to Tolmie, a proposal that was unanimously supported by the convention. Once again, however, Tolmie refused. According to journalist Russell R. Walker, it was because “he had given his wife his sacred promise that he would not accept the leadership even if it were offered him.” The exhausted yet determined delegates would not accept his refusal. The executive of the party, along with Conservative mlas and mps, met with Tolmie for more than an hour and eventually broke down his very real resistance, appealing to him as a loyal British Columbian. The convention then dissolved with a combination of enthusiasm and relief.

In most respects, Tolmie was a good compromise candidate, even if he was regarded, in the words of Walker, as “too kind-hearted a man for political leadership.” He was an imposing figure, whom Sydney Wayne Jackman described as “of gigantic size, weighing some three hundred pounds at his peak,” and who, “bubbling over with humour and friendliness, … exuded good will.” He may have been very amiable, but as historians Robin Fisher and David Mitchell put it, he was “more at home at a country garden party than in the rough and tumble of British Columbia politics.” Tolmie decided to play the role of honest broker as a leader, without engaging in the factionalism Conservatives had become well known for, and he continued in his role as a federal mp, awaiting the next provincial election.

1928 provincial election

When the election was announced for 18 July 1928, Tolmie immediately resigned his seat as a federal mp, returning to British Columbia by train. He diligently campaigned throughout the province by automobile, frequently repeating his slogan: “British Columbia, Canada and the Empire.” He would greatly benefit from the fact that the tired and unpopular Liberal Party had governed for more than a dozen years and was now led by the uninspiring John Duncan MacLean*, the long-time chief lieutenant of Premier John Oliver, who had died in office the previous year. Tolmie’s Conservatives had another advantage: the Provincial Party, which had split the vote in the previous general election, now seemed a spent political force.

Premier of British Columbia

The Conservatives won the general election of July 1928 decisively, with more than 53 per cent of the popular vote and 35 of the 48 seats in the legislature. Tolmie won his seat of Saanich with a comfortable lead of over 500 votes against his Liberal opponent. Flushed with victory, Premier Tolmie, who now also assumed the role of minister of railways, fashioned a cabinet made up largely of inexperienced politicians who, like himself as a newcomer to provincial politics, seemed to believe the booming British Columbia economy would continue to grow for the foreseeable future. And for the first year, it did. Tolmie’s most notable achievement during his first few months in office was his negotiation with the federal government to return to British Columbia the unalienated portion of the Canadian Pacific Railway’s land grant. Despite the province’s prosperity, he did not increase social welfare benefits, and educational grants were reduced. After the stock-market crash of October 1929, however, the provincial resource-based economy was especially vulnerable. With each passing month, as the steep economic decline grew more painfully evident, it became clear that the Tolmie administration was almost completely unprepared to deal with such a calamity. By 1931, the unemployment rate in British Columbia was the highest in Canada at 28 per cent.

As unemployment escalated, the provincial government’s modest relief efforts had very little impact. Attracted by the mild weather, the jobless from other parts of the country, and notably those displaced by the devastating drought in the prairies, flocked to British Columbia. The government’s creditors were becoming restless and alarmed by the mounting provincial debt. Calls for assistance from the federal government, now led by Tolmie’s former colleague, Conservative Richard Bedford Bennett, were received unsympathetically. All of this contributed to a return to political infighting among provincial Conservatives, with Tolmie’s grip on the premiership appearing weak and his leadership inadequate for the challenges of the times.

Kidd report

The combination of rapid economic decline and increasing political agitation, including defections from Conservative ranks, prompted Premier Tolmie to accept, albeit reluctantly, the appointment of a committee of leading Vancouver businessmen to investigate the finances of British Columbia. Its report, informally known as the Kidd report after the name of its chairman, the Vancouver chartered accountant George Kidd, was completed in the summer of 1932, but its recommendations were far too radical for Tolmie and his cabinet to consider seriously. It advised the government to make extreme cuts to education and social services, institute a total ban on increases in taxation and provincial borrowing, and reduce the size of the cabinet, legislature, and civil service. In many respects, the report’s proposals mirrored the platform of the now defunct Provincial Party.

Conservatives divided

Tolmie rejected the recommendations of the Kidd report but decided, somewhat in desperation, to advance the initiative of a union government to deal with the economic crisis. This was not an original idea; Tolmie’s experience in Borden’s Union government during the First World War was a probable point of reference. He offered former Conservative leader Bowser and the new Liberal leader, Thomas Dufferin Pattullo*, positions in his cabinet. Both refused. On 22 April 1933 Premier Tolmie addressed a Vancouver meeting of the executive of the Conservative Party, noting that there was “a public demand throughout the Province of submerging party politics.” It was increasingly evident, however, that he could not lead such an effort. The popular impulse towards non-partisanship in British Columbia was trumped by perceptions that Tolmie’s days as premier were probably numbered.

Not only was Tolmie under intense pressure, but while on his way to Ottawa in the spring of 1933 to plead for more federal government support, he was informed of the death of his wife. The result was even more political hesitation. During the final legislative session of his administration, Tolmie received news of more defections from his caucus and Bowser’s efforts to form the Non Partisan Independent Group – Conservatives by a different name – which would never fully get off the ground owing to Bowser’s death just eight days before the election.

1933 provincial election

Premier Tolmie, indecisive and ineffective in his final year in office, hung on to the bitter end. The five-year constitutional limit of the government ended in September, with an election called for 2 Nov. 1933. The autumn campaign was rather unusual. The Conservative Party did not officially contest the election. Instead, each local association was to act independently: some candidates ran under the banner of the Union Party of British Columbia (followers of Tolmie) or the Non Partisan Independent Group, while others ran as independent Conservatives or simply independents. Tolmie campaigned in a lacklustre fashion, mostly on Vancouver Island, and was no match for Liberal leader Duff Pattullo and his energetic “Work and Wages” campaign or for the newly organized socialist party, the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF). The various Conservative factions received just 16 per cent of the vote and three seats, with Tolmie’s Unionists garnering only four per cent and one seat. Tolmie was defeated in his own riding. At the time of writing, there has been no Conservative premier of British Columbia since his defeat.

Last years

Tolmie, who had been very hurt by the wholesale rejection of his party and the loss of his own seat, retired to his old family homestead. In 1936 he would be partially vindicated when he decided to contest a federal by-election in Victoria, winning the seat and returning as a Conservative mp in Ottawa. He died the following year and was buried in the Royal Oak Burial Park in Saanich. Simon Fraser Tolmie would leave a legacy of affable and folksy leadership that proved insufficient to deal with the policy challenges of the Great Depression and the unforgiving partisanship of British Columbia politics.

BCA, “Genealogy,” Simon Fraser Tolmie, Victoria, 15 April 1867 (baptism), Simon Fraser Tolmie and Mary Ann Harrap [Harrop], Victoria, 6 Feb. 1894 (marriage); Simon Fraser Tolmie, Saanich, 13 Oct. 1937 (death); PR-0160. Jean Barman, The west beyond the west: a history of British Columbia (Toronto, 1991). B.C., Committee appointed by the government to investigate the finances of British Columbia, Report (Victoria, 1932). Electoral history of British Columbia, 1871–1986 ([Victoria, 1988]). Robin Fisher and D. J. Mitchell, “Patterns of provincial politics since 1916,” in The Pacific province: a history of British Columbia, ed. H. J. M. Johnson (Vancouver, 1996), 254–72. R. E. Groves, “Business government: party politics and the British Columbia business community, 1928–1933” (ma thesis, Trent Univ., Peterborough, Ont., 1973). S. W. Jackman, Portraits of the premiers: an informal history of British Columbia (Sidney, B.C., 1969). R. A. J. McDonald, “Sir Charles Hibbert Tupper and the political culture of British Columbia, 1903–1924,” BC Studies (Vancouver), no.149 (spring 2006): 63–86. I. D. Parker, “The Provincial Party,” BC Studies, no.8 (winter 1970–71): 17–28; “Simon Fraser Tolmie: the last Conservative premier of British Columbia,” BC Studies, no.11 (fall 1971): 21–36. R. R. Walker, Politicians of a pioneering province (Vancouver, [1969]).

Cite This Article

David Mitchell, “TOLMIE, SIMON FRASER,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 20, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/tolmie_simon_fraser_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/tolmie_simon_fraser_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | David Mitchell |

| Title of Article: | TOLMIE, SIMON FRASER |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2026 |

| Year of revision: | 2026 |

| Access Date: | January 20, 2026 |