GALT, JOHN, author and colonizer; b. 2 May 1779 in Irvine, Scotland, son of John Galt, a ship’s captain, and Jean Thomson; m. 20 April 1813 Elizabeth Tilloch in London, and they had three sons, including Thomas and Alexander Tilloch*; d. 11 April 1839 in Greenock, Scotland.

John Galt was born into a part of Scotland where class distinctions were rapidly breaking down, and where intellectual horizons were expanding as a result of the Scottish Enlightenment and the French revolution. His father’s profession and the sight of vessels on the Clyde evidently expanded John’s geographic horizons, but his eccentric mother, and her picturesque phraseology, were much more important in the formation of Galt’s character and what he called his “hereditary predilection for oddities.” Ill health cut him off from other children, fostered introspection, and threw him into the company of the old women who lived behind his grandmother’s house. The young Galt listened to their recollections and stories and became an avid consumer of ballads and tales, the influence of which in his literary career he characteristically admits in his Literary life. Mrs Galt scorned her son’s bookishness (and fascination with flowers), and she tried to direct him into more active and public pursuits. Her hopes for his worldly success counterbalanced the retiring strain in his character, and perhaps contributed to the lifelong tension he felt between literary and “active” endeavour. In his Autobiography Galt mentions that her death in 1826 “weakened . . . the motive that had previously impelled my energies.”

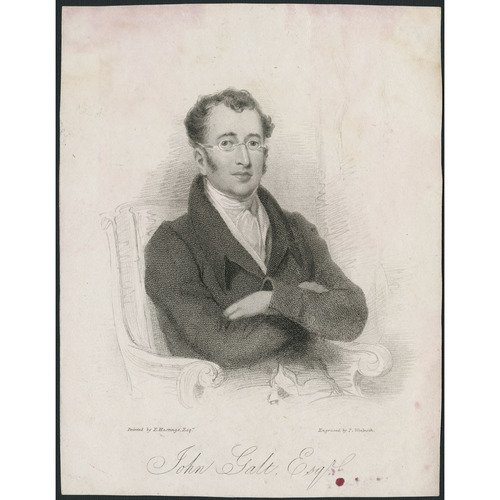

Galt’s physical appearance was always out of the ordinary. A schoolmate, G. J. Weir, remarked that at the age of 7 he was as tall as a boy of 14. In his youth he developed a sense that he was destined to be distinguished by other than his looks and “herculean frame.” Galt was fully aware of his limitations, and was “very early impressed with the necessity of rendering myself the architect of my own elevation.” His education was sporadic because of his ill health and his family’s movements between Irvine and Greenock, where they finally settled around 1789. He was tutored at home and at local schools. A university education for someone of his background would not have been unusual in Ayrshire at the time, but a mercantile career seems to have been expected by both Galt and his parents. He entered the Greenock custom-house at around the age of 16 and left it soon after for a clerkship at the local firm of James Miller and Company.

Galt’s informal education was greatly advanced by the formation of a literary and debating society with two schoolfellows, William Spence and James Park. In 1804 they hosted a gathering with the poet James Hogg, the celebrated Ettrick Shepherd, who reported that their conversation “was much above what I had ever been accustomed to hear.” Their friendship, cut short by the ill-health and early deaths of Park and Spence, not only set Galt’s priorities, in that culture and literature would follow the mercantile business of the day, but also expanded his intellectual horizons by providing a forum in which competition was encouraged and criticism dispensed. Spence was more interested in mathematics, and Park in literary criticism, than in literary creation. Galt’s combative nature led him to compete with them in their own fields of endeavour. The double life Galt led at this time resulted in the development of a decisiveness and an orderly working routine which gave him “a great deal more leisure than most men.” His observation in 1834 that in “considerably less than two years of great suffering, I have been enabled to dictate and publish ten volumes – much of them from bed,” confirms the efficacy of his system and his “sedentary industry.”

By 1804 Galt had distinguished himself by assiduity in business, by his involvement with the Greenock Library, by the publication of some poems in the Greenock Advertiser and the Scots Magazine, and by initiating a corps of volunteer sharpshooters in response to what he called the second revolutionary war in France. Yet he was restless, and when his employers received an insulting letter concerning their method of business, Galt over-reacted, pursued the culprit, and held him till he had forced a written apology from him. This incident, possibly coupled with an unhappy love affair (the girl died), resulted in Galt’s decision to go to London in May 1804. The chief aim of this first and most dramatic of Galt’s migrations was to go into business on his own, which, after a lonely few months, he accomplished. The factor and brokerage partnership he commenced in 1805 with a fellow Scot, John McLachlan, was soon bringing in the then considerable sum of £5,000 per annum. In 1807 he published, in the Philosophical Magazine, his first essay on North America, his hastily compiled “Statistical account of Upper Canada,” which stemmed in part from his interest in emigration to the New World as a means of relieving over-population in Europe. For this article he drew on information supplied by William Gilkison*, a cousin and former schoolmate who had spent time as a ship’s captain on the Great Lakes. Galt’s commercial success must have given him a high profile in the City, and was sufficient for his father to make over to him a large sum of money. However, the complexity of the business and a correspondent’s failure (described by Galt in the Autobiography) led to severe losses and the dissolution of the partnership in its third year.

This failure at the moment when some of Galt’s “inordinate ambitions” had been realized, forced him to withdraw into the study of law at Lincoln’s Inn; yet his health soon collapsed and he sought relief in travel in 1809. His wanderings did not conform to the usual grand tour but were dictated by fruitless schemes to circumvent Napoleon’s blockades by establishing a trade route through the Ottoman empire. A further attempt, at Gibraltar with the firm headed by Kirkman Finlay, came to naught when Lord Wellington’s Iberian victories rendered the operation unnecessary, and, as at most moments of crisis, Galt again fell ill. He returned to London in 1811, married two years later Elizabeth Tilloch, daughter of the publisher of the Philosophical Magazine, and turned to his pen as his main source of income.

After his return Galt produced two entertaining books of travels at his own expense, and in 1812 he brought out a collection of five of his tragedies and a well-researched Life and administration of Cardinal Wolsey, which went into several editions. The critics were far from kind concerning the plays: Walter Scott commented in a letter that they were “the worst ever seen.” His first book of travels, however, enjoyed considerable success. Galt noted that sales had paid for his extensive touring. In 1816 he published the first part of a biography of the American painter and president of the Royal Academy of Arts, Benjamin West. Throughout this period Galt also produced numerous school textbooks, mainly under the pennames Sir Richard Phillips and John Souter, but the exact quantity of non-fiction he wrote is hard to uncover, not least because in the course of his career Galt used at least ten pseudonyms and often published anonymously. He admitted that his early literary efforts were undertaken to “acquire the reputation of a clever fellow,” but his business and literary reverses, and his desperate need for money (he had a growing family and had chosen to divide his father’s estate with his mother and sister), changed his literary goal. What he later called his last work as an amateur author, The Majolo, a Sicilian tale, was published in 1816.

The earthquake (1820), which Galt called his first serious novel, was a commercial failure, but his play The appeal (1818) was performed with some success and, according to Galt, Scott contributed the epilogue. In 1820 his literary fortunes changed with the immediate popularity of William Blackwood’s serialized publication of his epistolary novel The Ayrshire legatees, an ironic, Smollettian account of a Scottish family’s voyage to London to collect an inheritance. This was followed in 1821 by the work for which Galt is still best known, Annals of the parish, published in book form by Blackwood to critical acclaim.

Although Annals was often taken for a novel, Galt referred to the group of works to which it belongs as “theoretical histories.” Written in the fictional autobiographic form of which he is one of the earliest, most innovative, and prolific exponents, the book chronicles, through the eyes of a village priest, the social and industrial changes Galt observed sweeping across Ayrshire. His preservation of west country dialect was and remains relished by Scots, and the care he took is confirmed by his instruction to Blackwood “not to touch one of the Scotticisms.” Yet his use of dialect somewhat hampers the modern North American reader of his Scottish works. Galt’s fictional realism was maintained in Sir Andrew Wylie (1822), the exactitude of his portrait of Lord Sandiford being confirmed when Lord Blessington, the unsuspecting model, told Gall that he found Sandiford’s character “very natural, for, in the same circumstances, he would have acted in a similar manner.” Galt’s documentary powers were justly praised, but his powers of imagination were sometimes criticized. In the Autobiography and Literary life, he took pains to point out that “originality” was his characteristic as a writer, and that his best works were proof that he could have done better if literature had been his sole pursuit.

The Countess of Blessington became Galt’s literary patroness. Her assistance and Galt’s connection with Lord Byron (with whom he had travelled in the Mediterranean in 1809–10 and of whom in 1830 he would publish a much-criticized but much-read biography) helped Galt achieve prominence. In his Literary life, he remarks that he knew more noblewomen than female commoners, and was acquainted with upwards of 60 members of parliament. After the success of The Ayrshire legatees, Galt had pursued his literary career energetically, almost all his best-known Scottish “Tales of the west” being published between 1820 and 1822. The provost (1822), the fictional story of a municipal politician, has been compared by literary historian Keith M. Costain with Machiavelli’s The prince, and when taken with Galt’s The member (1832) and The radical (1832) confirms his important and early contribution to the development of the political novel. The impact of Galt’s work on politicians, in a century in which the power of literature was immense, is hard to assess, yet it is worth noting that George Canning read The provost in parliament at a single sitting. The success of Galt’s Scottish stories (The last of the lairds was to be added in 1826) seems to have turned his head, and, boasting that his Scottish resources were superior to those of Scott, he embarked on a series of historical novels; three nearly forgotten works, Ringan Gilhaize (1823), The spaewife (1823), and Rothelan (1824), were the result.

By the early 1820s Galt’s dormant business career was revived with his involvement in what would become the Canada Company. The firm had its origins in efforts by loyalists along the Niagara frontier of Upper Canada to gain redress for damages caused by American troops during the War of 1812. Galt had made a name for himself as a parliamentary lobbyist, particularly when his stratagems facilitated the passage of a bill to construct the Union Canal in Scotland in 1819. This renown, distant family connections in North America, and his authorship of “Statistical account of Upper Canada” a dozen years before made him a likely choice to represent loyalist interests, and the promise of a three per cent commission spurred him on. The British government, however, proved reluctant to pay reparations and subsequent efforts by Galt to raise a loan, with which to liquidate the claims, collapsed. Galt then thought, probably at the urging of an old friend and Upper Canadian resident, Roman Catholic priest Alexander McDonell, of using the colony’s own resources. The scheme: sell its crown and clergy reserves, set aside under the Constitutional Act of 1791, and use the revenue in part to pay off his constituents.

Despite Galt’s high hopes, nothing much came of this plan, at least immediately, but the idea of disposing of the reserves was timely. It eventually resulted in another scheme spearheaded by Galt which saw him organize a group of City merchants and bankers into a joint-stock company to buy the reserve lands and then sell them at a profit to British emigrants. By 1824 Galt was secretary of a projected one-million-pound corporation which included some of the City’s senior financial figures. Two years of wrangling with government followed before a charter was granted to the Canada Company on 19 Aug. 1826. During this time Galt devoted most of his considerable energy to the project and in the spring of 1825 he visited Upper Canada as one of five commissioners charged with evaluating the lands to be purchased. Disputes with local figures, particularly Attorney General John Beverley Robinson* and the Reverend John Strachan*, resulted in the church moiety of the reserves being replaced by a million acres of wilderness, later called the Huron Tract. The final settlement saw the company opt to purchase one and a third million acres of crown reserves throughout the colony, the Huron Tract, and scattered lands amounting to more than a million acres. The price: a uniform 3s. 6d. an acre.

Galt was charged with running the company’s field operations and he took up residence in Upper Canada in December 1826. He plunged into a welter of activity. Establishing an office at York (Toronto), he attended to an accumulation of offers to purchase land. In April 1827 he founded with much ceremony the town of Guelph and, following a policy of relatively large-scale capital investment, moved rapidly to develop it as a nucleus for settlement (he was much influenced by hothouse settlements such as the Holland Land Company and the Pulteney estates, which he had visited in western New York) [see David Gilkison*]. Later Galt travelled to Lake Huron on an exploring expedition, arriving in late June at the camp of Canada Company warden William Dunlop and surveyor Mahlon Burwell. Here Galt established another instant town, Goderich. By the autumn of 1828 a road had been built to the site from Guelph. The development of the latter town had continued at a rapid pace into 1828; Samuel Strickland* was hired to manage the company’s affairs there and to complete the works begun by Galt. In 1827–28 Galt was also involved in setting up company agencies elsewhere in North America.

The peculiar, inverted society of the little town of York did not know what to make of a man with Galt’s vision and purpose. Galt, for his part (and curiously, since in his New World novels he was to demonstrate that he knew the peculiarities of isolated communities), blundered by associating with such political reformers as John Rolph*; by socially mingling with those out of favour with the local establishment, including the wife of John Walpole Willis*; and by rashly but understandably withholding funds due to the government in order to assist the indigent La Guayra settlers, a group of British immigrants whose attempt to settle in South America had failed and who, in the absence of official arrangements, had been directed to the Canada Company in Upper Canada. Galt, never sufficiently deferential, fell out with Lieutenant Governor Sir Peregrine Maitland*, his secretary (Major George Hillier), Archdeacon Strachan, and the “family compact.” Galt’s religious tolerance and his sympathy for the Six Nations Indians, whose land claims he had represented in England in 1825 [see Tekarihogen* (1794–1832)], hindered his acceptance into the narrow and partisan society of York. His sense of conspiracies directed against him (as depicted in the Autobiography) verged on the paranoid, yet his primary problem, exacerbated by distance from London, was the fear of the company’s directors that he was spending too much money and furnishing insufficient accounts. In fact, Galt was an appalling bookkeeper, and he had spent too much time on developmental schemes in the company’s larger holdings, particularly the Guelph block and the million-acre Huron Tract, rather than selling off lands easily accessible from York or by road and water-way, or the scattered crown reserves. Canada Company accountant Thomas Smith was sent out in the spring of 1828, ostensibly to help him, but in actuality to investigate, and when Smith decamped to London with some of the company’s papers, Galt decided to return as well to reassure the directors. On reaching New York early in 1829, he learned that he had been recalled; his replacements were Thomas Mercer Jones* and William Allan*. Galt arrived in England on 20 May. The newspapers had carried news of his recall, his creditors closed in, and he was soon imprisoned for failure to pay his sons’ school fees.

As with many business failures of this nature, the facts remain murky. Galt’s recall coincided with a drop in confidence in company shares on the London market. Certainly details of the dismal record of the novelist’s day-to-day sales and management had not matched the showy grandeur of his spectacular road-openings and town-foundings. A more sober on-the-job superintendence would be achieved by his successors. There is no doubt, however, that Galt’s prominent part in the establishment of the Canada Company was an important step in the development of the colony. Often controversial [see Frederick Widder*], the firm played a major role in the settlement of the province and was not wound up until its last lot was sold in the 1950s. Although Galt’s business reputation had been severely injured by his recall, by 1833 – when, largely because of the efforts of Jones and Allan, company shares were the highest vendible stock on the market – he was able to float a colonial business venture, the British American Land Company, formed to develop lands in the Eastern Townships of Lower Canada. Galt served as secretary but was forced to resign in December 1832 because of his health.

While in prison, Galt had again turned to his pen for income and, with the help of old publishers such as Blackwood and new ones such as Henry Colburn and Richard Bentley, he wrote himself out of jail chiefly by putting to use his Canadian experiences. Lawrie Todd (1830), Bogle Corbet (1831), and his Autobiography (1833), the works by which Galt’s stature as a New World author is usually judged, followed his release in November 1829 in quick succession, though he was by now severely hampered by what appears to have been arteriosclerosis. During his last five years, he was wracked with pain and was a self-admitted invalid. His literary output, however, continued strong in book form and in periodicals. In 1834 Galt and his wife moved from London to Greenock. The three-volume Literary life appeared that year, and Fraser’s Magazine remained an outlet for his journalistic talents. By 1837, however, he was slowing down, producing only minor efforts, reviews, and some verse. He died at Greenock on 11 April 1839.

Canada’s claim to Galt is tenuous since he was resident for less than three years. He had intended to immigrate permanently, but it was his sons who became established in the Canadas, in 1833–34 (his eldest, John, became registrar of Huron County; Thomas became a chief justice of Ontario; and the youngest, Alexander Tilloch, worked for the British American Land Company, and was a father of confederation and Canada’s first high commissioner in London). John Galt’s connection with the Canada Company would, he felt, be remembered “when my numerous books are forgotten.” Between 1807 and 1836 (the whole of his active life) he published more than 30 items which relate to North America, the majority of them concerning the Canadas. He was well aware that the foundations of new national identities were being laid, and in his “American traditions” articles in Fraser’s Magazine and other writings he communicates his excitement at being actual and literary midwife to a new sense of national consciousness in the Canadas. As early as 1813, in his archly titled Letters from the Levant, Galt mentions his interest in “everything tending to preserve, heighten, and perpetuate those public affections, which, although it has become fashionable to decry them as prejudices, are still the sources that contribute to, elevate, and sustain the dignity of nations.”

With a keen eye for encouraging beneficial “national prejudices,” Galt depicted North American society, from the pauper immigrants of Lawrie Todd to the genteel ones of Bogle Corbet. His use of American slang in Lawrie Todd and the contrast with it of the language used in the Canadas in Bogle Corbet (which precedes the first of Thomas Chandler Haliburton*’s Sam Slick books by five years) create important social and historical records. Galt was convinced that the accuracy of his portraits of pioneer life, which he believed were superior to those by American James Fenimore Cooper, would ensure their increasing value. Critic Elizabeth Waterston has observed that Bogle Corbet was the “first major work to define Canadianism by reference to an American alternative.” It is also the story of an anti-hero, and Galt’s frequent use of non-military male anti-heroes, especially in Bogle Corbet and the Autobiography, demonstrates a belief that “‘the man who makes a blade of corn grow where it never did before, does more good to the world than did Julius Cæsar.’” Other critics, such as Clarence G. Karr, have suggested that self-interest played a greater part in Galt’s career than he would have one believe. Certainly Galt petitioned the government for a percentage commission on the sale of crown lands, but he believed that his claim was just, that he had “add[ed] to the comforts of mankind” and had helped to “build in the wilderness an asylum for the exiles of society – a refuge for the fleers from the calamities of the old world and its systems fore-doomed.” As he remarks in his Literary life, “Nor do I ever recollect being vain of any praise that my own judgment did not in some degree ratify as deserved.”

It is impossible to calculate how much Galt’s efforts and ideas contributed to the creation of Canadian and American consciousness. It is, however, known that the Autobiography was reprinted twice in Philadelphia in the year of its publication in England, and that Lawrie Todd went through 17 editions by 1849. Contemporary advertisements indicate that some of Galt’s works were on sale in Upper Canada, The life of Lord Byron actually being reprinted in Niagara (Niagara-on-the-Lake) in 1831 by Henry Chapman. The value Galt himself placed on his North American works is indicated by the large amount of space he assigns to them in his Autobiography and Literary life.

Galt’s fame undoubtedly rests in Canada on his connection with the Canada Company, and in Britain on his Scottish “theoretical histories.” The geographic bifurcation of his activities, and his belief that business and literature are not incompatible, contributed to the decline of his reputation after his death. The division he himself imposed by writing a business life and then a literary life one year later further hampered appreciation of the magnitude of his achievements. Galt’s recall from Upper Canada at the height of his career as a colonizer crippled his North American pursuits, and his British reputation was injured by the disorganized state of his literary affairs at the time of his death. It is only recently that historians have re-established Galt’s importance to Canada, a country in which the role of business has been central, and that reappraisal and republication have confirmed Galt’s original and important contribution to British and North American literature. Though fine literary and historical studies of Galt exist, the definitive and well-rounded treatment of his importance to both continents and to the worlds of affairs and literature remains to be written.

[Most of the manuscripts of Galt’s published works have been lost or destroyed; those which survive are scattered along with his other papers among a number of institutions in Canada and Great Britain. The NLS, Dept. of mss, houses a substantial number of his letters along with some literary manuscripts; part of the miscellaneous collection of manuscripts which Mrs Galt took to Canada on her husband’s death is in the Galt papers at PAC, MG 24, I4, while further material is in his papers at AO, MU 1113–15. The AO also houses a fine and voluminous collection of Canada Company records, containing the texts of many of Galt’s business letters. The Colonial Office papers at the PRO, especially CO 42/367, 42/369, 42/371, 42/374, 42/376, 42/379–81, 42/383, 42/387–89, and the Upper Canada sundries at PAC, RG 5, A1, also include much material relating to Galt’s colonial ventures.

The Univ. of Guelph Library, Arch. and Special Coll., in the town Galt founded, is possibly the only institution attempting to acquire any printed or manuscript material by or relating to Galt, including variant editions of his published works and critical studies about him as a literary figure and colonizer. The library holds an extensive collection of published items, including many first and rare editions, as well as a number of relevant archival collections, most notably the recently acquired H. B. Timothy coll. and a number of Galt’s literary manuscripts, including his unpublished biography of Sir Walter Scott. There are smaller collections of Galt material in the Lizars family papers, the Goodwin–Haines coll., and the Canada Company papers.

Harry Lumsden, “The bibliography of John Galt,” Glasgow Biblio. Soc., Records, 9 (1931), and I. A. Gordon, John Galt: the life of a writer (Toronto and Buffalo, N.Y., 1972), form the key bibliographic sources. Gordon’s book, J. W. Aberdein, John Galt (London, 1936), and [D. M. Moir], “Biographical memoir of the author” (issued under the Greek letter delta in the 1841 edition of Galt’s The annals of the parish and the Ayrshire legatees . . . (Edinburgh and London), i–cxiii) are the soundest works on Galt’s literary career. P. H. Scott, John Galt . . . (Edinburgh, 1985), though limited in scope, is the first to accord the North American works their rightful place; two books of essays, John Galt, 1779–1979, ed. C. A. Whatley (Edinburgh, 1979), and John Galt: reappraisals, ed. Elizabeth Waterston (Guelph, 1985), collect the work of some recent critics of Galt.

The best scholarly guide to Galt’s involvement with the Canada Company is R. D. Hall, “The Canada Company, 1826–1843” (phd thesis, Univ. of Cambridge, Cambridge, Eng., 1973). Other sources are R. K. Gordon, John Galt (Toronto, 1920), H. B. Timothy, The Galts: a Canadian odyssey; John Galt, 1779–1839 (Toronto, 1977), Thelma Coleman with James Anderson, The Canada Company (Stratford, Ont., 1978), and C. G. Karr, “The two sides of John Galt,” OH, 59 (1967): 93–99.

Because Galt was so prolific, his writings on North American topics have been submerged by the weight of other material. The following chronological list of his publications relating to North America and colonial affairs extracts these titles from his other works for the first time, and while by no means exhaustive, serves as proof of his prolonged interest in New World affairs. “A statistical account of Upper Canada,” Philosophical Magazine (London), [1st ser.], 29 (October 1807–January 1808): 3–10. The life . . . of Benjamin West . . . (2. pts., London and Edinburgh), first published in 1816 and 1820 respectively; the 1820 editions of both parts have been reprinted as The life of Benjamin West (1816–20); a facsimile reproduction, intro. Nathan Wright (2v. in 1, Gainesville, Fla., 1960). All the voyages round the world . . . (London, 1820), written under the pseudonym of Captain Samuel Prior. “The emigrants’ voyage to Canada” and “Howison’s Canada,” published anonymously in Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine (Edinburgh and London), 10 (August–December 1821): 455–69 and 537–45. Editor’s preface to [Alexander Graydon], Memoirs of a life, chiefly passed in Philadelphia, within the last sixty years (Edinburgh, 1822). Three letters published under the pseudonym Bandana: “Bandana on the abandonment of the Pitt system . . . ,” “Bandana on colonial undertakings,” and “Bandana on emigration,” Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine, 13 (January–June 1823): 515–18; 20 (July–December 1826): 304–8, 470–78. “An aunt in Virginia,” an unpublished play written in New York in 1828, later adapted to prose and published as “Scotch and Yankees: a caricature; by the author of ‘Annals of the parish, &c.,’” Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine, 33 (January–June 1833): 91–105, 188–98. Galt also wrote, but did not publish, a farce entitled “The visitors, or a trip to Quebec,” described in his Autobiography [see below]. “Colonial discontent” (as Cabot), Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine, 26 (July–December 1829): 332–37. “Letters from New York . . .” (signed “A.”), New Monthly Magazine and Literary Journal (London), 26 (1829, pt.ii): 130–33, 280–82, 449–51; 28 (1830, pt.i): 48–55, 239–44. Lawrie Todd; or, the settlers in the woods (3v., London, 1830). “The Hurons: – a Canadian tale, by the author of ‘Sir Andrew Wylie,’” “Canadian sketches, – no.ii . . .,” “Canadian affairs,” “American traditions . . . ,” “Guelph in Upper Canada,” and “American traditions, – no.ii . . . ,” all in Fraser’s Magazine (London), 1 (February–July 1830): 90–93, 268–70, 389–98; 2 (August 1830–January 1831): 321–28, 456–57; 4 (August 1831–January 1832): 96–100. “The colonial question” (as Agricola) and “The spectre ship of Salem” (as Nantucket), Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine, 27 (January–June 1830), 455–62 and 462–65. Bogle Corbet; or, the emigrants (3v., London, [1831]). “The British North American provinces” (signed “Z”), and “American traditions, – no.iii . . .” Fraser’s Magazine, 5 (February–July 1832): 77–84, 275–80. The Canadas, as they at present commend themselves to the enterprize of emigrants, colonists, and capitalists . . . ; compiled and condensed from original documents furnished by John Galt . . . , comp. Andrew Picken (London, 1832). “Biographical sketch of William Paterson . . . ,” New Monthly Magazine and Literary Journal, [new ser.], 35 (1832, pt.ii): 168–76. “The Canada corn trade,” an unsigned review in Fraser’s Magazine, 6 (August–December 1832): 362–65. The autobiography of John Galt (2v., London, 1833). Introduction to Grant Thorburn, Forty years’ residence in America . . . (London, 1834). “The metropolitan emigrant,” Fraser’s Magazine, 12 (July–December 1835): 291–99. The list concludes with a series of nine “Letters concerning projects of improvement for Upper Canada,” printed in the Cobourg Star between 23 Nov. 1836 and 29 March 1837; these have been republished as “John Galt’s Apologia pro visione sua,” ed. Alec Lucas, OH, 76 (1984): 151–83. r.h. and n.w.]

Cite This Article

Roger Hall and Nick Whistler, “GALT, JOHN,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 7, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 4, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/galt_john_7E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/galt_john_7E.html |

| Author of Article: | Roger Hall and Nick Whistler |

| Title of Article: | GALT, JOHN |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 7 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1988 |

| Year of revision: | 1988 |

| Access Date: | December 4, 2025 |