Source: Link

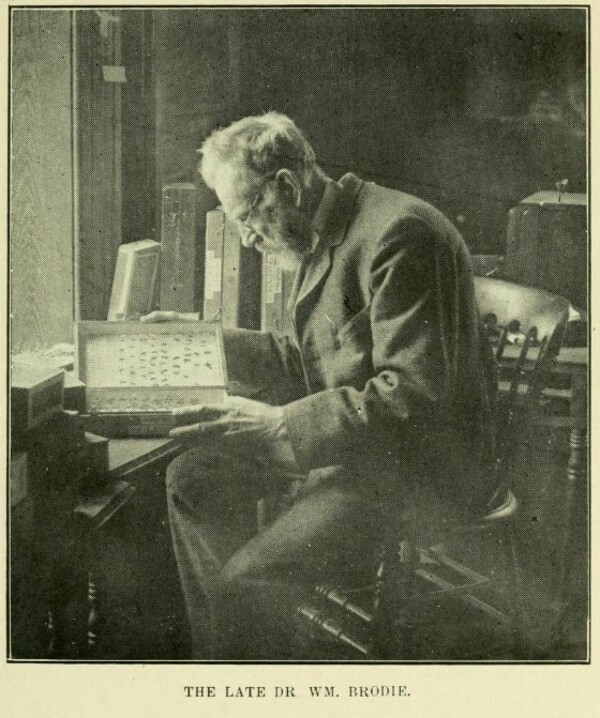

BRODIE, WILLIAM, dentist and biologist; b. 1831 (baptized 9 July) in Peterhead, Scotland, son of George Brodie and Jean Milne; m. Jean (Jane Anna) Macpherson (McPherson) of Whitby, Upper Canada, and they had one son and six daughters; d. 6 Aug. 1909 in Toronto.

William Brodie was four years old when his family moved to Upper Canada and, on the advice of William Lyon Mackenzie*, settled on a farm near Toronto in Whitchurch Township. There the influence of his educated and ambitious mother nurtured in Brodie a keen interest in the fauna and flora of his surroundings. After briefly attending local schools he became a teacher in Whitchurch and Markham townships. He also studied dentistry and on 20 Jan. 1870 was accepted as a member of the Royal College of Dental Surgeons of Ontario after writing its examinations. Brodie would practise in Markham and Toronto for over 40 years and was said to have been the first dentist in Toronto to administer chloroform to his patients to ease pain. But dentistry was “a means to making a living” so that he could devote time to natural history, especially entomology; his passion for the subject is alleged to have taken priority even over patients with toothaches at least once when he was carried away by discussions of insect specimens with a visitor and sent the patient to another dentist.

Brodie collected and studied specimens of all kinds and became a recognized authority in entomology and botany. He combined acute powers of observation with a probing mind that mastered a wide range of scientific and philosophical literature. “If he picked up a shell or a fossil,” reminisced one of his friends, “problems of antecedent conditions or of geological eras would be suggested; if he noticed a plant, some question of ecology or environment would present itself.” His enthusiasm for nature and frequent rambles along the rivers and into the woods of his environs generated charming wildlife stories. When he went out to interview the animals, he is reported to have explained, he invariably found it was the animals that were interviewing him. With his receptiveness to nature’s offerings, Brodie influenced many young disciples, including the writer Ernest Thompson Seton*, who was travelling with Brodie’s only son, a promising young naturalist, when the latter drowned while crossing the Assiniboine River in 1883.

In 1877 Brodie helped found the Toronto Entomological Society as an alternative to the Entomological Society of Ontario, which he felt neglected its scientific responsibilities to become a mere social club, and served as its president. The following year he renamed it the Natural History Society of Toronto, to include persons interested in zoology and botany; he was still president in 1885 when it amalgamated with the Canadian Institute as its biological section. He contributed in 1898 a series of articles about nature, including scientific entomology, for general readers in the “Home Study Club” of the Toronto Evening News, and he also drew attention to important interglacial geological structures revealed by excavations along the Don River. He had made his mark on the Toronto political scene by serving in 1877 as the first president of the local Reform Association.

By 1900 Brodie’s biological collections ranked among the largest and finest on the continent, and contained 100,000 specimens of Ontario flora and fauna, excluding fishes, birds, and mammals. He specialized in parasites, especially those which were introduced by plant-eating insects and caused plant damage known as galls, abnormal swellings of plant tissue. The United States Department of Agriculture recognized Brodie, shortly before his death, as the best authority in North America on this aspect of plant pathology, not only for the completeness and accuracy of his collections, but also for his analytical ability to trace and identify parasites of leaf-eating insects and to recognize new species. Once the symbiosis between parasite and plant was understood, Brodie went one step further to propose the importation, acclimatization, and controlled breeding of new parasites that preyed on insect pests. One such beneficial parasite, applied in keeping with his advice, is said to have helped save the fruit trees of California during an infestation.

In 1903 Brodie sold his collection of 18,000 galls to the Smithsonian Institution in Washington. When it offered to purchase the other 80,000 of his specimens, he sold them instead for the token price of $1,000 to the government of Ontario, which placed them in the Provincial Museum, housed at the Normal School in Toronto. In exchange for designating them to the province, Brodie was named curator of the provincial museum and provincial entomologist, and was finally able to retire from dentistry. In his new position he continued to advise farmers on the various insect pests which threatened their crops, until his death of pneumonia in 1909.

Brodie’s scientific career reflected the transition from the older study of natural history with its emphasis on the description and classification of natural objects, to biology and the study of living things. He rejected the traditional emphasis on morphology in favour of a greater focus on ecology, the relation of living things to their environment. While Brodie remained sceptical about Charles Darwin’s theory of natural selection, arguing that it was tautologous, he none the less accepted evolution as “the modern system of Philosophy, and presumably the most natural” because it gave “a fuller and truer expression to the ‘Order of Nature’ than any of the former systems” had done. “Nature is said to be a dear old nurse,” he explained to a non-specialist audience in 1895, “and we love to rest on her lap and listen to her wonderful tales and enchanting music; but she is many-sided, and on one side is implacable and cruel as the grave. Her constant demand is ‘conform,’ and what does not is ruthlessly trampled down.” He tempered his scientific convictions by drawing upon both western and eastern philosophical traditions to comprehend evolutionary processes within a universal, even mystical context that lent a deeper meaning to the apparent harshness of nature. At the same time, his musings about insect intelligence and consciousness tied his work to early psychological theory about the nature of mental functions.

Brodie’s pioneering work in the use of natural predators against crop infestations was overshadowed by the subsequent development of the chemical pesticide industry. However, his approach found support in later generations faced with new environmental concerns. Brodie’s scientific accomplishments, his international reputation, and his personal influence as a nature-lover contrast sharply with his relative isolation from other prominent Canadian entomologists, except for a few exchanges with Abbé Léon Provancher*, and the comparatively small number of his formal publications. This contrast underlines his status as a transitional figure whose importance in Canada to both the history of science and the tradition of nature writing is easily overlooked.

Most of William Brodie’s articles were published in the Canadian Entomologist (London, Ont.) and the Canadian Bee Journal (Beeton, Ont.). A chronological listing of these and several other contributions is available in Science and technology biblio. (Richardson and MacDonald). In addition, Brodie and John E. White compiled Check list of insects of the Dominion of Canada for the Natural Hist. Soc. of Toronto (Toronto, 1883). A small collection of Brodie’s personal papers is housed in the Royal Ontario Museum Library and Arch. (Toronto), SC 20A.

Univ. of Toronto Arch., A82-0003/002. Univ. of Toronto Library, Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, ms coll. 127 (J. L. Baillie papers), box 25. Hist. of Toronto, 2: 17.

Cite This Article

Suzanne Zeller, “BRODIE, WILLIAM,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 3, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/brodie_william_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/brodie_william_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | Suzanne Zeller |

| Title of Article: | BRODIE, WILLIAM |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1994 |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | March 3, 2026 |