Source: Link

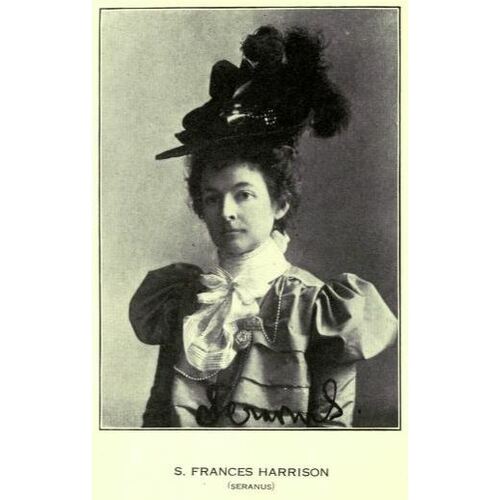

RILEY, SUSAN FRANCES (Harrison), known as Seranus, musician, author, journalist, educator, lecturer, editor, and translator; b. 24 Feb. 1857 in Toronto, only child of John Byron Riley and Maria (Mary) Ann Drought; m. 25 July 1877 John William Frederick Harrison (1847–1935) in Toronto, and they had a son, who predeceased her, and a daughter; d. there 8 May 1935.

Susan Frances Riley’s parents were of Irish descent. Her father was born in Quebec and her mother in Dublin; both belonged to the Church of England. John Riley managed an inn on Toronto’s Front Street, which was purchased by Thomas Dick* in 1862, after which Riley established the nearby hotel Revere House. It would become a gathering place for promoters of the Canada First movement. He also co-owned Riley and May, which manufactured billiard tables. Susie, as she was called, was educated at a private institution and studied with the renowned pianist Frederic Boscovitz. In her mid teens she went to a ladies’ school in Montreal, where she began to write verse under the name Medusa. On prize day she recited her first noteworthy effort, “The story of a life.” She attended the philosophy classes of John Clark Murray* at McGill University, joined the Montreal Ladies’ Literary Association, and wrote potboilers for British and American magazines while still a teenager.

Susie returned to Toronto in 1876, and the following year she became the choir director at the new Church of the Ascension on Richmond Street, which attracted prominent low-church Anglicans. That summer she married John William Frederick Harrison, who had moved from Bristol, England, two years earlier to become the organist at St George’s Anglican Church, Montreal. The Harrisons relocated to Ottawa in 1877 when he accepted the positions of organist and choirmaster of Ottawa’s Christ Church Cathedral and music director of the Ottawa Ladies’ College. He revived the Ottawa Philharmonic Society and is credited for some of the first Canadian performances of works by Bach and Mendelssohn, in which his wife often performed as a singer or piano accompanist. She participated in “Canada’s welcome”: a masque, part of the celebrations for the arrival of Governor General Lord Lorne [Campbell*] and Princess Louise in 1878. Five years later she wrote the words and arranged the music for an address to Lorne’s successor, Lord Lansdowne [Petty-Fitzmaurice*]. With the completion in 1884 of the comic three-act Pipandor, set in 16th-century France, she became the first Canadian woman to compose an opera. The music manuscript has apparently been lost; it is believed that she adapted French Canadian tunes to create a score somewhat analogous to a Gilbert and Sullivan operetta. Of her extant compositions the most expansive is a set of three sketches for piano.

S. Frances Harrison was the name she used after marriage, and when in 1882 the first part of her signature was misread as “Seranus,” she decided to employ it as a nom de plume, often placing it in quotation marks below her name; it appears on her gravestone. Previously she had used G. R. and the Rambler, and she published some songs and piano compositions as Gilbert King, which was also her byline as music correspondent for the Detroit Free Press. But it was as Seranus that she became well known for her creative writing, through which she expressed thoughts about the development of the young dominion and explored how nationalism could be fostered. Unlike Canada First members William Alexander Foster* and Charles Mair*, whose work reflected English Canadian sensibilities, Seranus was passionate about the culture of French Canada, having “imbibed the feeling of Quebec” (Canadian Magazine, 1898) in her youth, and it would be a lifelong interest and source of inspiration.

In 1886 the Harrisons, now with two young children, moved to Toronto, where John became organist at Jarvis Street Baptist Church. He was also a piano and organ instructor for the Toronto Conservatory of Music, established in 1886 by Edward Fisher*, whom the Harrisons would have known from music and teaching circles in Ottawa. Seranus would serve as principal of the Rosedale branch of the conservatory for 20 years, operating from their home. She became involved in various literary and musical associations, and her energy seemed to know no bounds. As part of an 1888 fund-raiser for the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts, she directed dancers, actors, and singers in “The masque of May Day,” for which she wrote the libretto and selected and arranged the music.

During this decade Seranus drafted three novels set in Canada; two of them, “The rock, a romance of Gaspé Beach” (c. 1885) and “Search for a Canadian” (1887), which compares the histories and cultures of Canadians and Americans, were never published. The third, The forest of Bourg-Marie, would not appear until late the following decade. Despite receiving accolades for her writing talent – as early as 1877 the man of letters George Stewart* had listed her among Canada’s good poets in an address to the Canadian Club in New York – she could not find a book publisher in the dominion. She had journeyed to London, England, and New York in the early 1880s to seek interest but was unsuccessful. This led her to self-publish in 1886 a collection called Crowded out! and other sketches. The semi-autobiographical title story hints at her frustrations through the words of a male narrator: “I have come to London to sell or to part with in some manner an opera, a comedy, a volume of verse, songs, sketches, stories. I compose as well as write. I am ambitious.… If nobody will discover me I must discover myself. I must demand recognition.” The settings in the ten short stories and one novella range from Europe to Ontario. John William Garvin would later reflect on the book’s significance in Canadian poets (Toronto, 1916): “It was in point of time the first attempt to put Muskoka, and the feeling and landscape of Lower Canada, before our people in an artistic way.”

The year after the family settled in Toronto, Seranus compiled The Canadian birthday book, the first anthology to include French and English poems as well as native verse in translation. Among the 150 authors represented, in works dating from as early as 1732, are Thomas D’Arcy McGee*, Joseph Howe*, Isabella Valancy Crawford*, Susanna Moodie [Strickland*], Charles Sangster*, Louis Fréchette*, Pamphile Le May*, the Marquess of Lorne, and Seranus herself. The title of her own first published collection of verse, Pine, rose and fleur de lis, released in 1891, underscores her developing belief that Canada’s identity had to be based on a blending of native, British, and French heritages. In this widely lauded work, she displays her expertise in various forms, including the complex 19-line villanelle, whose structure requires five tercets and a concluding quatrain, with repetition of words and even whole lines. As Marjory Jardine Ramsay Willison [MacMurchy] would state in a Canadian Bookman (Toronto) profile in 1932, “This French form of verse, light as a bird’s feather, in Mrs. Harrison’s hands is held and turned like a flashing blade.” Over the course of two decades Seranus’s villanelles, which number more than 100, and other poems would appear in several Canadian, British, and American magazines, and between 1889 and 1936 her work was included in important anthologies such as Theodore Harding Rand*’s A treasury of Canadian verse … (Toronto and London, 1900).

Despite the praise she received, Seranus felt underappreciated; she possessed what scholar Jennifer Chambers calls “a sense of self-importance … but also a sense of vulnerability.” In an 1895 letter to American poet and critic Edmund Clarence Stedman, who had decided to include two of her poems in an anthology he was editing, she wrote: “I really was the first writer in Canada to attract general attention to the local colour, so to speak, of the French. Fully eight years before [William Douw] Lighthall[*], [William] McLennan[*], [Duncan Campbell] Scott[*] or any others attempted the subject, I had brought out – in Ottawa, therefore wasted – a little book of short stories dealing with the habitant. In fact, I have always looked upon this as my special subject, yet – you know how sometimes the pioneer is forced to fall behind.” In an article featuring the American author and critic William Dean Howells, printed in the May 1897 issue of Massey’s Magazine (Toronto), she expressed her bitterness about the struggles faced by dominion authors:

Canada is the grave of a good deal of talent … and we (speaking of Canadian authors) have sometimes difficulty in impressing ourselves on foreign publishers, the only publishers worth anything to us. A great deal of good work is done in Canada which does not find its way into other countries. And there may be work which is a little too good for Canada, and yet, not quite good enough for English or American markets. Then, if we are to excel in local colour, we must remain in Canada in order to observe it, live it, so to speak, and so – you see.

The following year, The forest of Bourg-Marie would at last bring Seranus a contract and the recognition she had long desired from both sides of the Atlantic. Critics appreciated the novel’s sensitive portrayal of Quebecois culture. Among the themes is the lure of the United States; the main character moves there in search of financial reward and becomes corrupt and estranged from his native land. In her final novel, Ringfield (1914), the characters are again French Canadian, and she explores the impact of industrialization, the theme of American influences, and the differences between European and Canadian landscapes.

Seranus promoted francophone culture in her musical pursuits as well. Throughout the 1890s she presented well-received lecture-recitals in Toronto, London, Montreal, Boston, New York, and other cities. A review in the Montreal Gazette (8 May 1896) notes that “the gifted lady who undertook the task of giving to her hearers the literary as well as the musical side of the folk-songs of New France” is “an accomplished pianist and the possessor of a sweet and sympathetic voice.” As a member of the Toronto branch of the Women’s Art Association of Canada, she gave talks and organized musical events, and in 1901 her Canadian premiere of Samuel Coleridge-Taylor’s Ballade in A minor in its keyboard version was received favourably. On 17 April 1902 a complete program of her original works, including piano pieces, arrangements of French Canadian songs, selections from Pipandor, hymns, and sacred quartets, was presented at the Conservatory Music Hall.

Seranus was equally busy as a journalist. For a time she was the music editor of the Week, which had been founded in 1883 by Goldwin Smith*, and from December 1886 until the following June she also served as its editor. Over its 13-year existence, no other female writer would have more poems printed in its pages. For the Globe and for the Mail, she wrote music criticism and other opinion pieces. She edited the Conservatory Bi-Monthly newsletter, under the name Mrs J. W. F. Harrison, throughout the years of its existence, 1902–13, and contributed entries to Canadian music encyclopedias and the journal Musical Canada as well as several essays for the Conservatory Quarterly Review. Occasionally, she also translated French poetry into English for various journals.

Following a two-year battle with cancer, in March 1930 the Harrisons’ son died in Winnipeg, where he had worked in the insurance business. Not long afterwards, Seranus’s husband had what may have been a small stroke. The years of the Great Depression brought financial difficulties: the Harrisons’ daughter, son-in-law, and grandchildren had to move in with them. Seranus hesitated to approach Ryerson Press about publishing her verse because authors usually had to cover the production costs, and when she was invited to join a literary club she declined because she could not afford the fees. Yet until her death she remained the honorary president of the Toronto branch of the Canadian Authors Association (CAA), and only pressing duties could keep her from attending meetings.

Despite occasional illness and increasing frailty, Seranus continued to write. Her penultimate book, Four ballads and a play (1933), was described as “an artistic work which once more emphasize[s] the versatility and industry of this widely known Canadian author” (Globe, 3 Nov. 1934). Its one-act play is set in a northern mining camp and features characters of French, Scottish, Irish, British, and Russian background. Seranus’s final work, Penelope and other poems, was published the same year that she died after suffering a stroke. The many memorials in the press included that of educationist and author Edwin Austin Hardy*, who stated: “Mrs. Harrison was one of that outstanding group of Confederation poets, among whom there were five women, [Emily] Pauline Johnson[*], Isabella Valancy Crawford, Agnes Maule Machar[*], ‘Seranus,’ and Agnes Ethelwyn Wetherald.… Mrs. Harrison was not only a writer of Canadian literature, but used all her influence to stimulate an appreciation of Canadian literature” (Globe, 10 May 1935). Her funeral took place at the Church of St Simon-the-Apostle, where her husband had been organist and choirmaster from 1888 to 1916. She was buried in Mount Pleasant Cemetery and he beside her three weeks later. Among her pall-bearers were the academic Oscar Pelham Edgar* and journalist John Melbourne Elson*, past president of the Toronto branch of the CAA. In his comment to the press (Globe, 10 May 1935), the latter said: “In the death of Seranus Canada has lost one of its brilliant feminine minds.… She was gifted as a novelist, poet and musician, and there are few people who maintained so clear and keen a brain up to the very close of her career.”

Although Seranus probably overstated her pioneering status as a writer, her efforts to portray French Canadian culture to the country’s English-speaking majority must be acknowledged. At the same time she did not fear criticizing aspects of Quebec culture, particularly the influence of the Roman Catholic Church and the emphasis placed on women’s role of bearing children. A versatile writer in a wide range of genres, she consistently investigated the possibility of a unique national identity, clarifying the differences between the climate, topography, and political systems of Canada, the United States, and Europe. As a musician, she had more claim to being a pioneer: she was the first Canadian woman to compose an opera and likely the first to write a string quartet. The latter, based on Irish tunes, was performed at the 1902 concert of her own works, another first for a Canadian female composer. Although the quality of many of her published pieces is at the level of her potboilers, the more challenging works that survive reveal a competent composer.

Seranus is the compiler of The Canadian birthday book, with poetical selections for every day in the year from Canadian writers, English and French (Toronto, 1877), and the author of Pine, rose and fleur de lis (Toronto, 1891); The forest of Bourg-Marie (Toronto, 1898); Ringfield: a novel (Toronto, [1914?]); and Later poems and villanelles (Toronto, 1928). She also self-published Crowded out! and other sketches (Ottawa, 1886); In northern skies and other poems ([Toronto?, 1912?]); Songs of love and labor (n.p., [1925?]); Penelope and other poems: a new book of verse (n.p., n.d.); and Four ballads and a play (n.p., [1933]). Her stories, poems, and articles appeared in Belford’s Monthly Magazine, Canadian Courier, Canadian Magazine, Globe, Massey’s Magazine, Rose-Belford’s Canadian Monthly and National Rev., and Saturday Night (all published in Toronto); Stewart’s Quarterly (Saint John); American Magazine and Cosmopolitan (both published in New York); Atlantic Monthly, Living Age, and New England Magazine (all published in Boston); and Nash’s Pall Mall Magazine and Temple Bar (both published in London).

Some of Seranus’s poems appeared in important anthologies: Songs of the great dominion …, selected and ed. W. D. Lighthall (London, 1889); A Victorian anthology, 1837–1895 …, ed. E. C. Stedman (Boston and New York, 1895); Selections from the Canadian poets, chosen and ed. E. A. Hardy (Toronto, 1907); Canadian poets, ed. J. W. Garvin (Toronto, 1916); Canadian singers and their songs: a collection of portraits, autograph poems and brief biographies, comp. E. S. Caswell ([3rd ed.], Toronto, 1925); Canadian verse for boys and girls, chosen and ed. J. W. Garvin (Toronto, 1930); Cap and bells: an anthology of light verse by Canadian poets, chosen by J. W. Garvin (Toronto, 1936); and A treasury of Canadian verse, with brief biographical notes, ed. T. H. Rand (Toronto and London, 1900; repr. Freeport, N.Y., 1969).

At the first meeting of the Ont. Library Assoc., held in Toronto in 1901, Seranus delivered an address on the influence of scenery upon character in Canadian literature. Her early literary criticism appeared under the name Medusa and her music criticism under Gilbert King or G. R. in Canadian Illustrated News (Montreal) and Rose Belford’s Canadian Monthly Magazine and National Rev. (Toronto). She contributed “Historical sketch of music in Canada,” in Canada, an encyclopædia of the country: the Canadian dominion considered in its historic relations, its natural resources, its material progress, and its national development, ed. J. C. Hopkins (6v., Toronto, 1898–1900), 4: 389–94; an entry on Canada in the fifth volume of The imperial history and encyclopedia of music, ed. W. L. Hubbard et al. (12v., New York and Toronto, n.d.), 5 (History of foreign music, 231–53); and articles in the journal Musical Canada (Toronto). For the most complete listing of literary writings and poems that appeared in the Globe, see S. M. Leigh, “Susie Frances Harrison: an approach to her life and work” (ma thesis, Univ. of Western Ont., London, 1980).

The music for Pipandor, a comic opera in three acts (Ottawa, 1884) does not survive, but the libretto by F. A. Dixon does. The published libretto of “Canada’s welcome”: a masque (Ottawa, 1879) by F. A. Dixon and A. A. Clappé, which was presented with Mrs Harrison singing the role of Canada, is extant. Her string quartet, called Quartet on ancient Irish airs (n.p., n.d.; published as part of the Canadian music heritage series, score available at the Canadian Music Centre, cmccanada.org), may be the first work composed by a Canadian woman for more than three parts. Published under the name S. F. Harrison is Trois esquisses canadiennes (Montreal, 1887); pianist Elaine Keillor recorded the first movement (“Dialogue”) on the CD “By a Canadian lady”: piano music, 1841–1997 (Nepean, Ont., [1999]) and the third movement (“Chant du voyageur”) on Sounds of north: two centuries of Canadian piano music (Brossard, Que., 2012). For a compilation of Seranus’s other known compositions, including those she signed as Gilbert King, and for a select list of her articles on musical topics, see Elaine Keillor, “Susan Frances Harrison (1859–1935),” in Women composers: music through the ages, ed. Sylvia Glickman and Martha Furman Schleifer (8v., New York, 1996–2006), 7 (Composers born 1800–1899: vocal music, 2003), 416–26.

In 1935 the composer E. W. Devlin based Rose Latulippe: a Canadian folk-play in one act … (Toronto) on Seranus’s ballad “Rose Latulippe: a French-Canadian legend,” which had been published in the Week (Toronto), 23 Dec. 1886: 59; it would become the basis for three Canadian ballets (all titled Rose Latulippe), featuring music by Maurice Blackburn (n.p., 1953), Harry Freedman (n.p., 1966), and Michael McLean (n.p., 1979).

AO, RG-80-5-0-70, no.13363; RG-80-8-0-1555, no.3830. LAC, R11472-0-X, Can. West (Ont.), dist. Toronto, subdist. St George Ward: 137. Globe, 13 April, 4 May 1901; 10, 11, 13 May 1935. Globe and Mail, 12 June 1937. “The art fair,” Week, 31 May 1888: 431. “Books and authors,” Canadian Magazine, 12 (November 1898–April 1899): 181–83. Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1912). Jennifer Chambers, “Unheard Niagaras: literary reputation, genre, and the works of Mary Agnes Fleming, Susie Frances Harrison, and Ethelwyn Wetherald” (phd thesis, Univ. of Alta, Edmonton, 2005). Margot Kaminski, “Challenging a literary myth: long poems by early Canadian women” (ma thesis, Simon Fraser Univ., Burnaby, B.C., 1998). Elaine Keillor, “Evolution of women composers in Canada: part 2 – biography of Susie Frances Harrison (1859–1935),” Assoc. of Canadian Women Composers, Bull. (Toronto), spring 2004: 5–6. Carrie MacMillan, “Susan Frances Harrison (‘Seranus’): paths through the ancient forest,” in Silenced sextet: six nineteenth-century Canadian women authors, ed. Carrie MacMillan et al. (Montreal and Kingston, Ont., 1992), 107–36. “S. Frances Harrison (Seranus),” in Canadian poets, ed. J. W. Garvin (Toronto, 1916), 123–32. A. E. Wetherald, “Some Canadian literary women – I: Seranus,” Week, 22 March 1888: 267–68. M. J. Willison [MacMurchy], “Mrs. J. W. F. Harrison – ‘Seranus,’” Canadian Bookman (Sainte-Anne-de-Bellevue, Que.), July 1932: 80–81.

Cite This Article

Elaine Keillor, “RILEY, SUSAN FRANCES (Harrison), known as Seranus,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed June 28, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/riley_susan_frances_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/riley_susan_frances_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Elaine Keillor |

| Title of Article: | RILEY, SUSAN FRANCES (Harrison), known as Seranus |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 2022 |

| Access Date: | June 28, 2025 |