Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

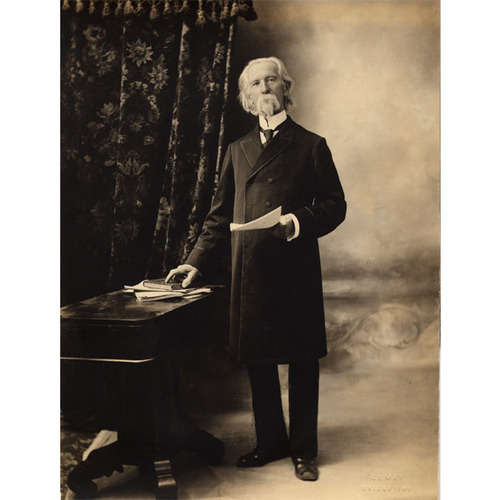

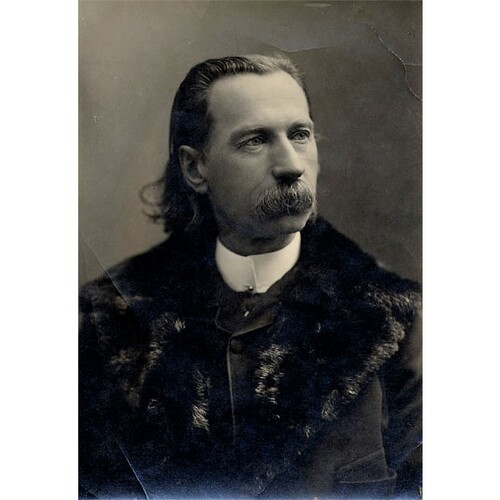

LE MAY, PAMPHILE (baptized Léon-Pamphile Lemay, he signed both Lemay and LeMay, before finally adopting Le May), lawyer, librarian, writer, and translator; b. 5 Jan. 1837 in Lotbinière, Lower Canada, fifth of the 14 children of Léon Lemay and Marie-Louise Auger, who kept a general store and inn on Saint-Eustache concession; m. 20 Oct. 1863 Marie-Honorine-Sélima Robitaille at Quebec, and they had 14 children; d. 11 June 1918 in Deschaillons, Que.

Pamphile Le May had rather irregular elementary and secondary schooling, first at the parish school, and from 1846 to 1849 at the college run by the Brothers of the Christian Schools in Trois-Rivières. He next studied Latin with notary Thomas Bédard in Lotbinière, and in 1854–57 he took the classical program at the Petit Séminaire de Quebec, from the fourth year (Versification) to the sixth year (Rhetoric). He left the seminary in July 1857 because of frail health. After a year’s rest, he began the study of law and he became an articled clerk in June 1858. Within a month he abandoned law and went to the United States, seeking employment in Portland, Maine, but he found nothing that suited him. On his return he worked for a few weeks as a store clerk in Sherbrooke, but he soon was given to understand that he was not cut out for the world of business.

Le May returned to his parents’ home and for about a year studied philosophy privately to prepare himself for the priesthood. In 1860 he began a course in theology with the Oblates in Ottawa, but he dropped out for reasons of health after less than two years. In the end he went back to the study of law, working at the same time as a supernumerary translator in Quebec at the Legislative Assembly of the Province of Canada. This job left him the time for creative literary endeavours. On 4 July 1865 he was called to the bar.

In late October 1867 the premier of Quebec, Pierre-Joseph-Olivier Chauveau*, who was eager to encourage promising young writers, offered Le May the position of librarian to the new provincial Legislative Assembly. Le May began his duties on 27 December. The 25 years he spent in this post enabled him to lead an independent life and enjoy a comfortable retirement. His work was not always a sinecure. On two occasions he had to build up the collection almost from scratch. When he took up his employment, he found the library scant, with but a few hundred books, mainly on civil law. After the fire of 19 April 1883, only about 4,500 volumes remained. Much of Le May’s work consisted in buying books to meet the needs of the legislators, in fields such as law, history, political economy, and science, even though he would have preferred sometimes to acquire more poetry and literature. For purchases abroad he had the assistance of middlemen, but on at least one occasion the questionable behaviour of an agent in Europe, Arthur Dansereau, who had submitted double invoices, nearly got him into trouble. In the legislature in May 1886 the solicitor general, Edmund James Flynn*, tried to implicate Le May; he was vigorously defended, however, by mla James McShane and the attempt failed. Encouraged at first by Pierre-Étienne Fortin*, the speaker of the assembly in 1875–76, Le May had instituted a system of exchanging parliamentary documents and books with the United States, France, Belgium, Norway, and Brazil and with other British colonies.

In the period 1867–83 Le May prepared several catalogues of the library’s books. After the fire he drew up a list of the ones that were left (the 1884 catalogue) and began filing new acquisitions on index cards by alphabetical order and subject matter, as the big American and European libraries did. In 1892 the library held 33,804 volumes.

It is to Le May’s credit that he kept the Legislative Library open to the public despite the criticism this practice sometimes attracted. Occasionally during his tenure, regret was expressed at the loss of newspapers and books. According to Le May, the situation was due to a shortage of space and staff. Like his successors, he had to fend off accusations of negligence, but in spite of everything he insisted on maintaining the library’s semi-public status.

On 22 Sept. 1892 Le May was obliged to retire at the age of 55; he would be replaced by Narcisse-Eutrope Dionne. This forced retirement was one aspect of the new Conservative government’s policy of dismissals, which affected other writers of a liberal cast of mind in the public service, such as Arthur Buies*. After his departure Le May sometimes let his bitterness show in his writing.

During and after his 25 years as librarian, Le May pursued a literary career. His avocation had become apparent in the late 1850s, when he joined the literary movement that sprang up at Quebec with François-Xavier Garneau*, Joseph-Charles Taché*, and Antoine Gérin-Lajoie* among others. Le May’s output was abundant and varied – eight collections of poetry and as many works of prose. He tried his hand at most literary genres – epic and lyric poetry, the short story, novel, essay, and lecture, tragedy, comedy, fable, and tale. He began by contributing poems regularly to magazines and newspapers, and then gathered them together in his first collection of poetry, Essais poétiques (Québec, 1865). In 1870 he published two long, quasi-epic poems, for which he had been awarded gold medals by the Université Laval: La découverte du Canada, written in 1867, and Hymne national pour la fête des Canadiens français, written in 1869. He composed several other works of epic or lyric poetry: Les vengeances: poème canadien (1875), La chaîne d’or (1879), Fables canadiennes (1882), which were all published at Quebec; and Les gouttelettes: sonnets (1904), Les épis: poésies fugitives et petits poèmes (1914), and Reflets d’antan (1916), published in Montreal. Of these works, Les gouttelettes: sonnets, the first collection of sonnets in French Canadian literature, shows greater striving for perfection of form; it is characterized by its intimiste tone, its delicacy and tenderness.

Le May also tried to make a name for himself as a novelist, publishing in 1877 at Quebec Le pèlerin de Sainte-Anne, a two-volume novel of more than 1,000 pages, and in 1878 a sequel, Picounoc le maudit, also in two volumes. Despite the unfavourable reviews from the critics, he brought out another novel, L’affaire Sougraine, in 1884. He also wrote Les vengeances: drame en six actes (1876), which was performed several times, and three comedies, which appeared in 1891 as a single volume entitled Rouge et bleu. After the lukewarm reception of his novels and plays, Le May turned to a genre that was more in keeping with his gifts and that led him to produce his best prose work, Contes vrais. It was published at Quebec in 1899 and a second edition came out at Montreal in 1907. A skilful storyteller, he sensitively reinterpreted the legends that form part of the French Canadian cultural heritage. He also translated two major works, Evangeline, by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, and The chien d’or/The golden dog, by William Kirby*.

Le May’s love of the countryside and the region where he lived permeates his work. The scenery of Lotbinière can be found in his novels, while Essais poètiques and Les vengeances (1875) describe the celebrations and entertainments of rural life (the feast of St Catherine, the game of Quat-Sept, the big sheaf, and the curé’s visit) and its drudgery (threshing grain and cutting and crushing hay). It was only in the country that Le May felt truly alive. In town he was bored and had difficulty finding inspiration. Like Louis Fréchette* and Octave Crémazie*, he was influenced by romanticism, but he was closer to Lamartine than Fréchette was, and more personal and sincere than Crémazie. Le May brought out the intimiste nature of poetry and made use of the cult of the soil, whereas the French Canadian poets of his time usually gave voice to the grand nationalistic themes and the great homeland.

Though calm and unpretentious, Le May’s life was not inactive. Between his large family, his garden, the Legislative Library, writing, his readers, and visits to the countryside, he had little time for travel, the social round, and politics, activities which held little attraction for him anyway. His trip to Europe in the spring of 1888 was apparently the only long journey he ever made. His social life consisted almost entirely of his family and meetings of various societies and associations. At these gatherings he usually read poems, as he did at the Royal Society of Canada (of which he had been a founding member in 1882), or a passage from a novel, as he did at the Société Casault in 1884. From time to time he gave a lecture or two as well. Le May received an honorary doctorate of letters from the Université Laval in 1888 and the rosette of an officier de l’Instruction publique of France in 1910. After his children had grown up, his most frequent visitors were his friends Fréchette, Napoléon Legendre*, Ernest Myrand, and Adolphe and Roméo Poisson.

As far as possible, Le May kept himself aloof from political life, which he considered a hornets’ nest or worse. He was in an ideal position, however, to observe the way of life of the middle class in the old capital. He portrayed their ambition, hypocrisy, and vanity in L’affaire Sougraine. In Fables canadiennes he ridiculed the self-importance, vanity, and arrogance of high society. In his comedies he satirized the nouveaux riches and political fanaticism (Rouge et bleu). A fiery poem published in Le Canadien in April 1870, lavishly praising Louis Riel* and justifying, in a way, the murder of Thomas Scott*, provoked a violent reaction. In Fréchette’s words, “This glorification of Riel caused an uproar, arousing terrible outbursts of anger. It was thought for a while that Riel and his poet were going to be hanged with the same rope.”

Le May seems not to have flaunted his Liberal allegiance while the Conservatives were in power. Later, however, he published poems in honour of Félix-Gabriel Marchand*, Honoré Mercier*, and Sir Wilfrid Laurier, mainly in Les gouttelettes, and his private correspondence after he had been forced into retirement contains a number of unfavourable references to the Conservatives. At the time of the November 1904 election, he found “the sudden collapse of the Bleus very amusing.”

Pamphile Le May lived at Quebec for most of his life, but in 1912 he moved to the home of his son-in-law, Ernest Saint-Onge, in Deschaillons. He agreed, nevertheless, to act as vice-chairman for the first convention of the Société du Parler Français au Canada, held at the capital in 1912 [see Stanislas-Alfred Lortie]. He died peacefully, surrounded by his family, on 11 June 1918 and was buried wearing the habit of a third order Franciscan. On 16 Sept. 1980, in recognition of his achievements, the Quebec government named the library building of the Assemblée Nationale after him.

In addition to the works already mentioned, Pamphile Le May is the author of Petits poèmes ([Québec], 1883) and Fêtes et corvées (Lévis, Qué., 1898). Manuscripts of his publications, as well as unpublished poems and correspondence, are preserved in the Fonds Pamphile-Léon-Le May (mss-176) at the Bibliothèque Nationale du Québec in Montreal.

ANQ-Q, CE1-29, 5 janv. 1837; CE1-97, 20 oct. 1863. René Dionne et Pierre Cantin, Bibliographie de la critique de la littérature québécoise et canadienne-française dans les revues canadiennes (1760–1899) (Ottawa, 1992), 209-10. DOLQ, vols.1–2. I. F. Fraser, Bibliography of French-Canadian poetry; part i: from the beginnings of the literature through the École littéraire de Montréal (New York, 1935), 74–77. Hamel et al., DALFAN, 863–65. J. E. Hare, “A bibliography of the works of Leon Pamphile Le May (1837–1918),” Biblio. Soc. of America, Papers (New York), 57 (1963): 50–60. G.-E. Marquis, “Un centenaire,” Le Terroir (Québec), 18 (1936–37), nos.2/3: 4–5. Maurice Pellerin et Gilles Gallichan, Pamphile Le May, bibliothécaire de la législature et écrivain (Bibliothèque de l’Assemblée Nationale, Québec, 1986). Cécile Saint-Jore, “Essai de bio-bibliographie sur la personne et l’œuvre de Pamphile Le May” (mémoire, école de bibliothéconomie, univ. de Montréal, 1939).

Cite This Article

Maurice Pellerin, “LE MAY (LeMay, Lemay), PAMPHILE (baptized Léon-Pamphile Lemay),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 7, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/le_may_pamphile_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/le_may_pamphile_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | Maurice Pellerin |

| Title of Article: | LE MAY (LeMay, Lemay), PAMPHILE (baptized Léon-Pamphile Lemay) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1998 |

| Year of revision: | 1998 |

| Access Date: | February 7, 2026 |