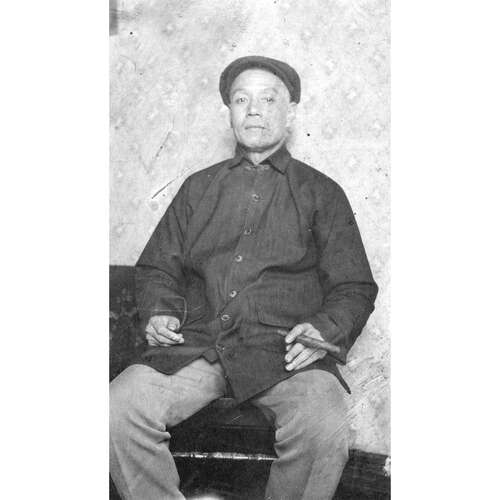

![[Studio portrait (possibly) of Chang Toy] - City of Vancouver Archives Original title: [Studio portrait (possibly) of Chang Toy] - City of Vancouver Archives](/bioimages/w600.11691.jpg)

Source: Link

CHANG TOY (Chen Cai in Mandarin), known also as Chan Doe Gee (Chen Daozhi) and Chan Chang-Jin, but generally as Sam Kee (San Ji)), labourer and businessman; b. 16 May 1857 in Cheong Pan village, Panyu county, Guangdong province (People’s Republic of China); m. twice, and had at least six sons and two daughters; d. 1921.

Chang Toy was of Hakka origin, a member of an ethnic and linguistic minority in Guangdong province. Although family tradition claims that his parents were farmers, several factors suggest that they were members of the local elite, even if they did not have gentry status. When Chang was three years old, his father died. Normally such a death would be a severe economic setback for a peasant family, but the fact that Chang was still able to receive three years of schooling indicates that his family did not need his labour to survive and hence was relatively well off. The circumstances of his first marriage, arranged when he was a child so that his mother could keep his child bride as a servant, also imply a certain prosperity. High status is further suggested by an incident involving his elder brother Boon Bak. Accused of counterfeiting, Boon Bak successfully intervened with a district magistrate to have the officials who had come to arrest him reprimanded, and apparently the charges were dropped as well. Boon Bak, whatever his activities, must have been sufficiently wealthy or well connected to gain the favour of the magistrate. Along with Yee Bak, Chang’s second eldest brother and eventual business associate, Boon Bak played an important role in Chang’s upbringing, teaching him martial arts. This training appears to have instilled in him considerable self-confidence, which stood him in good stead, both in China and in Canada.

Leaving his wife in China, Chang came to British Columbia in 1874 as a contract labourer. Like many other migrants from Guangdong, he had agreed to work in a fish cannery for a season in exchange for his passage money. Unfavourable winds delayed his ship’s arrival, so he had to work only for a month and a half to fulfil his contract. He then moved to Victoria, where he stayed for a short time at the Wing Chong Company. There he came to the attention of the proprietor, Chu* Lai, a Hakka from the same village. Chang declined an offer to join Chu’s business, but the two became close friends. Chu would even arrange Chang’s second marriage in 1892. Around 1876 he worked at a sawmill in New Westminster. While there, at the urging of the foreman, he used his martial arts training to knock down a white co-worker who had been harassing him and he thus earned the respect of his fellow workers. After a year at the sawmill Chang moved to Granville (Vancouver), where he bought an interest in a Chinese laundry, probably the Wah Chong laundry, which also sold a few Chinese groceries. Shortly after his arrival, Chang’s partner sold him his interest in the store. Chang then arranged for the Wing Chong Company to be his wholesale supplier. His store quickly became a contact point for other Hakka and natives of Panyu in search of work. He started contracting their labour for land clearing, salmon canning, and sugar refining. Within a few years he was also carrying on a trade in charcoal, operating three charcoal burners. The charcoal was a by-product of the land-clearing operations and was readily marketed to the Canadian Pacific Railway as well as to local consumers. After the great fire of 1886 in Vancouver, Chang moved to Steveston, where he opened a store and continued labour contracting.

The Sam Kee Company, for which Chang is best known, was operating in Vancouver by the early 1890s. Chang was the principal partner in the firm, which became an extensive import and export business. It acted as a wholesaler of rice and of merchandise from China for businesses owned by natives of Guangdong and Anglo-Europeans alike, while at the same time exporting commodities such as salmon and salt herring from British Columbia to China and Japan. Chang was the main supplier of capital for some of the fish packers with whom he dealt. For others he acted as a purchaser of supplies. Still others rented land, buildings, or equipment from him. In 1907 the company’s annual revenues were between $150,000 and $180,000 and it was one of the four most important firms in Vancouver’s Chinatown. The firm’s real estate holdings were also extensive. They included ten lots in Chinatown itself as well as lots in other parts of Vancouver and waterfront property and buildings in Nanaimo. In Vancouver it also owned five residential hotels in 1910 and operated another two for a German investor. These businesses were often fronted by Anglo-European factotums.

Chang’s business activities brought him into considerable contact with whites, even though he spoke little or no English. The closeness of these relations was demonstrated after the anti-Asian riot of 1907 in Vancouver. During the night of 6–7 September, following a rally organized by the Asiatic Exclusion League, a mob rampaged through Chinatown. Chang responded by sending his two younger sons to stay in the homes of prominent Vancouver citizens Ewan Wainwright McLean and John Joseph Banfield. In another instance, after the Chinese revolution of 1911, Chang was able to pressure the British authorities in Hong Kong to intercede with the Chinese government in Canton to get a shipment of lumber which had been waylaid delivered to its proper destination. His close connections to the Anglo-European business establishment did not delude Chang as to the extent of anti-Chinese racism. He had also responded to the riot of 1907 by proceeding with his partner, Shum Moon, who was president of the Vancouver Chinese Benevolent Association, to local gun merchants McLennan and McFeely, where they purchased the firm’s stock of revolvers to distribute to their fellow merchants. This activity occasioned considerable apprehension in the English-language community. At the same time Chang was not above profiting from the system of racial discrimination. By 1905 his company had become the Chinese agents for the Blue Funnel Line, which rivalled the CPR’s ships on the trans-Pacific route. Chang’s advertisements in Chinese specified that since the line had only one class of accommodation (unlike the Canadian Pacific) Chinese would face no discrimination on board.

Chang was also active within the Chinese community. He was one of a group of Chinese merchants who petitioned Vancouver’s city hall in 1899 protesting against indiscriminate police raids in Chinatown. A founder of the Chinese Empire Reform Association [see Yip Sang] in 1900, he served as president of its Vancouver chapter. In 1905 he established the association’s school and a suite for travelling scholars on the third floor of the Sam Kee Company building, sending his own children there. He was invited to be the first Chinese consul in 1908, but he refused on the grounds that his English was not good enough. Chang carried on business until 1920. He passed away the following year at an undetermined location.

Chang Toy was among the handful of migrants from China to Canada during the 19th century who were able to parlay business acumen, hard work, and family and ethnic connections into a sizeable fortune. By the early 20th century he was one of the leading merchants of British Columbia. His business interests spanned both sides of the Pacific and extended beyond the Guangdong ethnic sector into the mainstream of the British Columbian economy.

City of Vancouver Arch., Add. mss 571 (Sam Kee Company papers). Private arch., Theodore Chang (Vancouver), [Bob Chan], “Sanji huo Chen Cai (1857–1921)” (ms, n.d.); translated into English as “Chang Toy or Sam Kee (1857–1921)” (ms, n.d.). Vancouver Daily Province, 9 Sept. 1907. Harry Con et al., From China to Canada: a history of the Chinese communities in Canada, ed. Edgar Wickberg (Toronto, 1982; repr. 1988). Directory, B.C., 1882–85. Paul Yee, “Chinese business in Vancouver, 1886–1914” (ma thesis, Univ. of B.C., Vancouver, 1983); Saltwater city: an illustrated history of the Chinese in Vancouver (Vancouver, 1988); “Sam Kee: a Chinese business in early Vancouver,” BC Studies (Vancouver), nos.69/70 (spring/summer 1986): 70–96.

Cite This Article

Timothy J. Stanley, “CHANG TOY (Chen Cai) (Chan Doe Gee, Chen Daozhi, Chan Chang-Jin, Sam Kee, San Ji),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 12, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/chang_toy_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/chang_toy_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | Timothy J. Stanley |

| Title of Article: | CHANG TOY (Chen Cai) (Chan Doe Gee, Chen Daozhi, Chan Chang-Jin, Sam Kee, San Ji) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2005 |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | March 12, 2026 |