Source: Link

AITCHISON, ALEXANDER WILLIAM, manufacturer and fire chief; b. 20 May 1850 in Binghamton, N.Y., son of William Aitchison and Janet—; m. Martha Diana —, and they had five sons and three daughters; d. 5 April 1905 in Hamilton, Ont.

Alexander Aitchison’s parents emigrated from Scotland to the United States and lived in Binghamton until 1853, when they moved to Hamilton. Upon leaving school, Alexander went back to New York to be apprenticed as a carpenter. In 1870 he returned to Hamilton and worked as a foreman in his father’s planing mill and box-factory. After several years he was taken into partnership in the firm, Aitchison and Company, and given charge of the box department. He did not remain long in the business, however. Fire-fighting had fascinated him since his youth, when he had been a lantern-boy for a volunteer brigade. In November 1877 Hamilton City Council approved his appointment as a volunteer. Just 14 months later, on 14 Jan. 1879, he was hired as the city’s first full-time chief engineer, despite his inexperience.

In creating the position, the city had taken the first step in setting up a professional and disciplined fire department. Such departments were already in existence in Montreal, Ottawa, and Toronto. Hamilton’s major ratepayers had for some time demanded changes in order to reduce insurance premiums. Consultation with the local board of insurance underwriters to determine ways of lowering rates had resulted in council’s decision in 1875 to install an electrical alarm system and to man Central Fire Hall 24 hours a day. Council was the more anxious to set up a permanent force because, like municipal governments elsewhere, it had clashed with the volunteers over issues of control. In hiring the new chief, it purposely passed over applications from the part-time chief and his assistant, preferring Aitchison, whose short time on the brigade meant that he was relatively free from its traditions of independence.

Volunteer companies played a prominent role in the rich associational life of 19th-century Hamilton. Risking their lives to defend the property of others when they themselves owned little, the firemen believed that they were owed social esteem, pride of place in public processions, and autonomy in organization. They expected opportunities to socialize and to enjoy themselves around the fire-hall, indulging in annual suppers and beer and cheese after fires, entertaining visiting firemen, and going on excursions. Council, which provided the buildings, uniforms, and equipment, objected to its limited authority over the brigades and interpreted the firemen’s sociability as a lack of discipline and respectability. Making fire-fighting professional not only would improve the municipal protection of property but would give council control. Thus in 1879 the volunteer system was replaced. The new department of which Aitchison became chief consisted of 9 full-time firemen and 24 men paid to be on call.

The volunteer tradition died hard, however, and Aitchison’s appointment provoked controversy. In March 1879 a number of firemen and former volunteers publicly charged that he had been derelict as a volunteer, failing to turn out for half of the alarms and betraying cowardice in action. Initially, as chief, he knew less about fire-fighting and the equipment than his men; to compensate he displayed favouritism in hiring, bullied the men to do things which he could not or would not do himself, and fired his critics. A vigilance committee, probably comprised of the property owners who had lobbied council to hire him, was formed to defend him in the press. Though a minority on council remained sympathetic to the volunteers, the majority exonerated the chief, affirmed his authority to hire and fire, and bluntly rejected a proposal from former volunteers wishing to organize a new brigade.

Secure in his position, Aitchison began to discipline the department, as council had hoped. New regulations struck at several features of the volunteer system: no alcoholic beverages or gambling in the fire-halls, dismissal for contracting any debt for beer or liquor, no disorderly conduct on or off the job, no waste of materials, no acceptance of tips or rewards for services to the public, and no membership in political parties. The call-men, who were only part-time and thus less easily controlled by the chief, were dispensed with in 1881. The permanent staff was expected to wear uniforms on duty and to drill. Refusal to comply with the new regulations met with fines, suspension, or dismissal. Recalcitrant firemen even risked physical abuse at the hands of their burly chief, who in his prime stood over 6 feet 2 inches and weighed about 260 pounds. D. B. Skelly, the department’s engineer, was thrown out of the fire-hall and into the gutter for insubordination. He had refused to wear the departmental uniform, believing that his skill distinguished him from the other firemen and that he should not be expected to dress like them. Nor did he believe, as a skilled mechanic fully conversant with his machinery, that he needed to practise like the others. Council investigated the incident and ultimately supported the chief.

By 1886 Aitchison was firmly in charge. At a public banquet that year he was commended for “the up-hill battle he had to make the department what it is.” He responded with satisfaction: “Since assuming control of this department my aim has been to promote the efficiency and the moral standing of its members. . . . We have not only gained the good will of the citizens but of the insurance underwriters of Canada.” Three years later a deputation of citizens successfully petitioned council to raise his salary to $2,000.

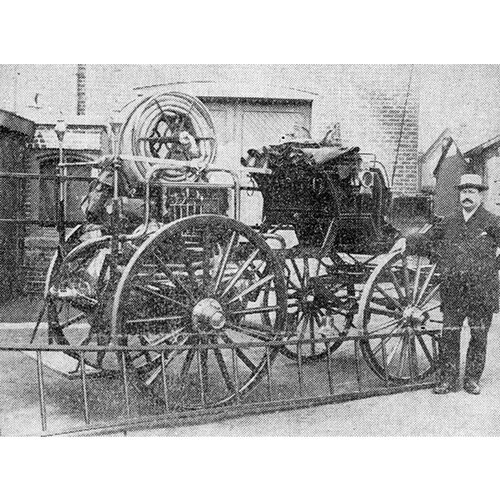

Though Aitchison’s greatest contributions were organizational and promotional, from 1879 he had sought new methods of fire-fighting. He learned something about electricity so that he could himself maintain and improve the alarm system, and he pressed council regularly for more and better equipment. Perhaps the controversy surrounding his appointment had convinced him of the importance of public opinion. With theatrical flair he held demonstrations in public to show that innovation was worth the expense. In 1888 a crowd of 2,000 was attracted to a demonstration of the department’s new chemical engine, obtained from a Toronto manufacturer, in which the mixture of sulphuric acid and a solution of bicarbonate of soda produced gas that forced out a stream of the solution. The following year Aitchison staged a surprise turn-out of the firemen at midnight for the press. Next day ratepayers read about the successful operation of the chiefs electrical system, which he had first seen in operation in Buffalo, N.Y., and which at the sound of the alarm automatically dropped the harnesses on the horses and opened their stalls.

The papers faithfully reported Aitchison’s exploits, his travels, and his participation in public events. Whatever basis in fact the early comments about his bravery may have had, no one later doubted his willingness to risk his life. He rushed into burning buildings to rescue residents and firemen overcome by smoke and he was once buried in smouldering ruins as a result. People scattered as his carriage sped through the streets and over sidewalks to get him to fires more quickly. About 1899 the chief was photographed as he hauled his 306-pound body to the top of a new 65-foot aerial ladder; the crowd was reported to have moaned as it swayed and bowed, but it did not break. In 1898 Hamiltonians were entertained by his attendance at the inauguration of several bath-houses on the bay. “Boys, I ain’t much of a swimmer,” he announced, “but I’m goin’ in.” The Hamilton Herald’s reporter was astonished at his plunge: “The wave that rose did not swamp the bath house, but it kissed the shine off the mayor’s boots and nearly drowned three or four small boys on shore.”

Alexander Aitchison’s death in 1905 was as sensational as his career. Rushing to a fire, he was killed when he was thrown from his red wagon after it collided with the chemical engine, which was speeding to the scene from another direction. Remembering the chief, the eulogist for the Hamilton Daily Times judged that “Alex. was a good man for news.” But news had also been good for Alex, since the transformation of public opinion was essential for the transformation of the fire department. The volunteer brigade that had enjoyed pride of place in public view no longer existed; the chief was the new hero, his celebrity legitimating his authority.

AO, RG 22, ser.205, nos.3946, 4030, 6119. Hamilton Municipal Cemeteries, Records for Hamilton Cemetery, sect.C9, lot 78-136. HPL, Arch. file, Hamilton Fire Dept.; Clipping file, Hamilton biog., A. Aitchison; Hamilton city records, RG 1, 1870–85; Scrapbooks, H. F. Gardiner, 139: 18; Hamilton Fire Dept.; Herald; Spectator; Times; Victorian Hamilton. Daily Times (Hamilton), 12 Aug. 1884; 5, 15 April 1905. Hamilton Herald, 11 Feb. 1898, 2 Feb. 1901. Hamilton Spectator, 1878–79, 1884–89, 3 June 1896, 12 Dec. 1898, 5 April 1905. DHB. Fire Journal (Toronto), February 1880: 1; March 1880: 9 (copies at AO). History of the Hamilton Fire Department ([Hamilton], 1920). B. D. Palmer, A culture in conflict: skilled workers and industrial capitalism in Hamilton, Ontario, 1860–1914 (Montreal, 1979), 46–49. Reginald Swanborough, “The early history of the Hamilton Fire Department, 1816–1905,” Wentworth Bygones (Hamilton), 8 (1969): 23–33.

Cite This Article

David G. Burley, “AITCHISON, ALEXANDER WILLIAM,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 10, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/aitchison_alexander_william_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/aitchison_alexander_william_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | David G. Burley |

| Title of Article: | AITCHISON, ALEXANDER WILLIAM |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1994 |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | March 10, 2026 |