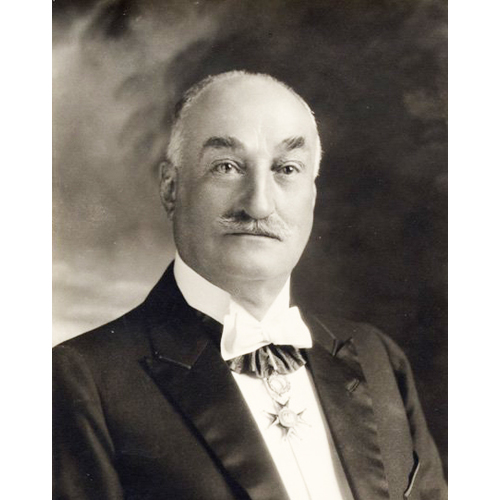

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

AMYOT, GEORGES-ÉLIE, manufacturer, businessman, politician, and philanthropist; b. 28 Jan. 1856 in Saint-Augustin-de-Desmaures, Lower Canada, son of Dominique Amyot (Amyot, dit Larpinière), a farmer, and Louise Nolin; m. 14 Nov. 1881 Joséphine Tanguay in Quebec City, and they had six children, five of whom survived; d. 28 March 1930 in Palm Beach, Fla.

Georges-Élie Amyot lived on a farm in Saint-Augustin-de-Desmaures until he was ten years old. He then moved with his family to Sainte-Catherine (Sainte-Catherine-de-la-Jacques-Cartier), where he attended school for a short time and was taught English by the Irish curé of the parish. At the age of 14 he went to Quebec; there he learned the trade of saddler from Louis Girard and entered into partnership with the saddler Louis Tanguay, his future father-in-law. In 1874 he joined his brother Bernard in New Haven, Conn., where the first manufacturer of corsets in the United States, the Strouse, Adler Company Corset Factory, had been founded in 1861; it had become the city’s principal employer. Amyot subsequently lived for a time in Springfield, Mass., engaged in his trade. When he returned to his home province in 1877, he was employed in Montreal as a clerk in the wrought-iron business and the boot and shoe industry. In 1879 he began working as a clerk for his cousins Joseph and George-Élie Amyot, who were importers of novelty items in Quebec’s Lower Town. He opened his own shop in the Upper Town in 1885, selling dry goods, fancy goods, and novelties. The following year, at the instigation of wholesaler Isidore Thibaudeau*, Amyot’s retail business was forced into bankruptcy. In 1894, when he was better off financially, he would reimburse his creditors, a gesture that his contemporaries said was unusual.

On 11 Oct. 1886 Amyot entered into a five-year partnership with Léon Dyonnet, who had been led to start manufacturing corsets by the success of the corset shop run since 1882 by his French wife, Hélène Goullioud, and her sister Clotilde. Each contributed $2,000 in capital, was entitled to half the profits, and could withdraw $800 a year for his personal expenses. Their agreement also stipulated that the two partners would be involved in every aspect of the business and that Dyonnet was to initiate Amyot “into all the manufacturing details and secrets and let him benefit from the experience he had gained in the said production process.” The question arises where Amyot had obtained this money so soon after his bankruptcy. It had probably come from his in-laws or from a fellow merchant, perhaps Pierre-Joseph Côté, to whom he owed an advance of $1,500 in the fall of 1887. In any case, in December 1886 Amyot’s wife renounced community of property, and thus put the family assets out of the creditors’ reach. On 26 March 1889, reportedly following Dyonnet’s departure for Brazil, the partnership was dissolved; in its stead the Dominion Corset Manufacturing Company was set up. Amyot’s partners were his sister Odile until her marriage in July 1890, and afterwards his older sister Marie-Louise until 9 Oct. 1897. He then continued in the Dominion Corset Company on his own.

The enterprise soon met with promising success, and rented larger and larger premises in the industrial section of Saint-Roch ward. In 1898 Amyot would purchase the bankrupt shoe factory of G. Bresse and Company [see Guillaume Bresse*] for $21,500. By November 1887 he was replacing the pedal-operated machines with steam-driven machinery, thereby substantially increasing his output and lowering the labour cost per unit. In his testimony to the royal commission on the relations of labour and capital in 1888 [see James Sherrard Armstrong*], he said that he had about 60 employees, including 10 to 15 girls aged between 10 and 14. Most of the goods he produced went to markets outside Quebec City, in particular to the Montreal wholesale outlet, which opened in 1889, and then to the Toronto office, which was set up in 1892. Sales grew from $21,000 in 1887 to $58,000 in 1891 and $130,000 in 1895.

This expansion led Amyot to invest in related activities. From 1894, to ensure himself a steady and cheap supply of the cardboard boxes required for shipping his products, he manufactured them himself in a building adjacent to his corset factory. This operation was initially an integral part of Dominion Corset, but from 1906 it was carried on by a separate entity, the Quebec Paper Box Company. In 1916 Amyot would set up the Canada Corset Steel and Wire Corporation to manufacture the steel rods used in the corsets.

Amyot also went into the production of beer, opening a brewery in 1895. His partner, Pierre-Joseph Côté, contributed two-thirds of the capital and, in return for a basic salary, was to devote his full time to managing the enterprise. The partnership agreement had a clause allowing Amyot to buy back one-sixth of Côté’s shares as well as to join him in working full-time in the business if its annual profits exceeded $10,000. This investment gave Amyot a contingency plan in the event that Dominion Corset failed. The brewery was located in Saint-Sauveur ward against the cliff where the spring water was drawn. On 12 Nov. 1896 beer merchant Michel Gauvin replaced Côté in the company, which became known as Amyot et Gauvin. It produced and distributed Fox Head beers, both ale and porter. In 1909, after buying Gauvin’s share and engaging in a number of highly profitable financial transactions, Amyot sold the business to National Breweries Limited for $226,500 in shares and debentures of that company, which was in the process of amalgamating most of the province’s breweries in Montreal and Quebec City.

From at least 1887, Amyot had been involved in politics. A member of the Liberal party, he focused mainly on finances and organization. He was particularly active in the debate on reciprocity with the United States, which by 1888 he supported. In 1897, a year after Wilfrid Laurier* came to power, a tariff reform was introduced that granted special concessions to Great Britain. In his dealings with Laurier, as well as in the Canadian Manufacturers’ Association (he was a member of the Quebec section) and the Quebec Chamber of Commerce (he served as president in 1906 and 1907), Amyot tried in vain to defend his business interests. He complained that the duty on imported corsets (which mainly came from Britain) had been lowered, while the duty on his raw materials – cotton and steel – were as high as ever.

When Charles Fitzpatrick* was appointed chief justice of the Supreme Court of Canada in 1906, a by-election became necessary in the federal riding of Quebec. Seeking a businessman to represent the city’s interests, Laurier offered the nomination to Amyot. His campaign, which was widely supported by the upper echelons of the Liberal party both federally and provincially, was organized by Cyrille-Fraser Delâge, the member of the Legislative Assembly for the same riding, and was financed by Amyot himself. Rebelling against the autocratic manner in which Laurier had chosen the candidate, a number of Liberals refused, however, to rally around Amyot. Lorenzo Robitaille, the 24-year-old son of a Beauport businessman, ran as an independent Liberal. He and his supporters attacked Amyot, calling him, among other things, a rich industrialist, an employer who treated his workers harshly, and Laurier’s man. Robitaille won the backing of Armand La Vergne*, and then of Henri Bourassa*. The Nationalistes thus used the situation to enter the fray, in order to demonstrate their opposition to certain measures taken by the Laurier government and to embarrass the party leadership. Memorable mass meetings drew the protagonists of both camps, raising the level of the debate and transforming a by-election that should have been run off quietly into a popularity contest between Laurier and Liberals loyal to him and the Nationalistes clustered around Bourassa. Clearly overtaken by events, Amyot struggled on to the end, but on 23 October he had to concede defeat by 388 votes. In December 1911 the premier of Quebec, Sir Lomer Gouin, with whom he was closely associated, appointed him legislative councillor for the division of La Durantaye.

Because of his success in industry and his political connections, Amyot was picked in January 1922 to take up the formidable challenge of saving the Banque Nationale, which had opened at Quebec in 1860, from bankruptcy. After a period of strong growth during the First World War, the bank found itself in a precarious position, mainly because of the financial problems of the National Farming Machine Limited, a company in Montmagny run by Charles-Abraham Paquet* [see Napoléon Lavoie*]. The firm had prospered as a result of the war economy, but when it tried to switch to producing farm implements, it experienced serious difficulties. In late 1921 it obtained between $3.8 and $4.5 million in advances from the Banque Nationale. This growing financial burden, along with a marked decrease in deposits from which the caisses populaires had in particular gained, posed a threat to the bank’s survival. Such was the situation in 1922, when four new directors were elected: Amyot, who also became president of the bank, Joseph-Herman Fortier, Sir Georges Garneau*, and Charles-Edmond Taschereau, the brother of Premier Louis-Alexandre Taschereau*. Scarcely had Amyot taken up office when he was obliged, with Gouin’s support, to make an urgent request to the federal minister of finance for a loan of $2.5 million. Unable to offer sufficient security, he received only $1 million, and he also failed in his bid for increased federal government deposits.

At the end of March, Amyot turned to the leading figures in the economic and political life of the province and the city of Quebec, inviting them to subscribe to a $1 million issue of capital shares. Despite the risks of double liability, Amyot himself took a block of $200,000 and got commitments from Napoléon Drouin* and Fortier (for $100,000 each), as well as from a number of other businessmen and politicians, including Premier Taschereau (for amounts ranging from $10,000 to $50,000). The $1 million was officially subscribed within a few weeks and was in by the end of 1922. From 1922 to 1924, Amyot, whose face appeared on the newly printed bank notes, tried to recover as much of the assets of the National Farming Machine Limited as possible and obtained large deposits from the provincial government. Despite his efforts, by the end of 1923 the situation had deteriorated to such an extent that a solution had to be found at once, in the form of a merger with the Banque d’Hochelaga. The premier persuaded it to absorb the Banque Nationale by guaranteeing it a reserve of $15 million in government bonds to balance the liquidity of the two banks. The bill providing for this assistance was passed on 24 Jan. 1924 and was vigorously defended by Taschereau, whom the opposition accused of trying to rescue Liberal friends threatened with sizeable losses, including Amyot. Once the merger was confirmed, Amyot became vice-president of the new Banque Canadienne Nationale, in which he maintained interests that were particularly useful to him in promoting his real estate and industrial endeavours.

Throughout this period Amyot had continued his cautious management of Dominion Corset. In 1901 it had about 320 employees and was producing 175 dozen corsets a day (in 125 different models) and 8,000 to 10,000 cardboard boxes. By the end of the first decade of the 20th century, its output had a total value of $500,000, of which roughly a third was sold in Ontario, 15 per cent in Montreal, 45 per cent in the rest of Quebec, the Maritimes, and western Canada, and 6 to 7 per cent in Australia and New Zealand. Sales rose from $560,000 in 1909 to more than $1 million in 1913, reaching $1.6 million in 1918 and $2.6 million the following year. This remarkable growth made it necessary in 1909 to expand the plant, but on 27 May 1911 it was devastated by a fire that destroyed part of the neighbourhood. Despite losses of $250,000, Amyot immediately rebuilt the factory, making it larger than ever. In the absence of internal accounting data, the company’s performance in some subsequent years is known only through the company’s minutes. Between 1911 and 1915 returns ranged from $100,000 to $200,000 per annum and rose noticeably afterwards. Information gathered by the Dominion Bureau of Statistics confirms that Dominion Corset increasingly dominated an industry that was tending to level off.

At the turn of the century Amyot already had sizeable financial resources, which he invested in real estate, among other things. In 1897, for example, he paid $6,000 cash for a fine property on Chemin Sainte-Foy in the suburbs of Quebec City. Over the years he had bought and speculated in real estate in other parts of the city (especially on the Grande Allée), in Montreal, and even in Saskatchewan and British Columbia. In the course of various subscriptions to Victory Loans, he himself, with $200,000 in 1917 and $500,000 in 1918, managed to come close to the amount contributed by the Price empire [see Sir William Price]. In the 1920s Amyot invested in and directed and promoted many projects, on his own, or through figureheads such as his son-in-law Henri Bray and his accountant Honoré-J. Pinsonneault, or as a member of some Canadian, British, or American politico-financial group. In addition to putting his money in real estate, he invested in numerous railway, shipping, and mining companies. During the winter he often spent time in resort areas in Europe (the French Riviera), the United States (Palm Beach, Fla), and Canada (Pointe-au-Pic, which would later become La Malbaie, in the Charlevoix region of Quebec), where he managed to make high-level personal and business connections. Direct and blunt, he did not skimp when it came to supporting causes dear to his heart, such as the church of Saint-Jean-Baptiste, the Asile du Bon-Pasteur, or the École Supérieure de Chimie at the Université Laval. In 1909 the minister of militia and defence, Sir Frederick William Borden*, appointed him honorary lieutenant-colonel of the 61st Regiment of Montmagny, a title he cherished.

Demanding but fair in his dealings with his employees, Amyot had brought his two sons into the business, beginning in 1906. Horatio, who had become deaf following surgery, was involved in the company’s operations in Toronto, western Canada, and then Montreal. Adjutor, the elder, also worked at finding new markets, especially in Australia and New Zealand and later England. Georges-Élie’s strong personality and thorough knowledge of the business world, however, left little room for Adjutor, who helped his father in the overall management but had little to do with day-to-day operations, which were entrusted instead to managers and accountants, including Pinsonneault. After putting in place an advantageous capital structure through various financial and legal transactions, Georges-Élie handed over control of Dominion Corset to Adjutor in 1924 through a private agreement. He transferred 11,499 of the 21,000 shares issued and subscribed, which were added to the 6,050 shares Adjutor already held, with the authority, however, to reduce the capital by selling them back to the company. In December of that year Adjutor conveyed all his shares except one to his father in trust, to be held until the latter’s death, but this agreement was cancelled in 1929. These manoeuvres ensured that Adjutor would inherit the business.

In 1928, to guarantee the distribution and preservation of the capital investment, Amyot drew up a will reflecting his own image – all of a piece and absolutely solid. It divided among his heirs, with the exception of Adjutor, the usufruct from a capital that would amount to some $5.5 million, distributable on the death of the last of his grandchildren. Including Dominion Corset, the Amyot empire was worth, in 1930, at least $8 million in pre-Depression dollars and it constituted one of the great fortunes of Quebec City at that time.

Georges-Élie Amyot died suddenly in Palm Beach on 28 March 1930. In the ensuing days, the arrival of his body and the magnificent funeral attracted the political and commercial elite of Quebec City. Amyot was buried on 3 April in the cemetery of Notre-Dame de Belmont, in a marble mausoleum he had had prepared in 1908, as befitted the remarkable success of a French-speaking Quebec industrialist who had become a financier and entrepreneur on a continental scale.

The author wishes to thank Marc Paquet, Robert Amyot de Larpinière, and Pierre Amyot for their valuable assistance.

ANQ-Q, CE301-S17, 29 janv. 1856; S103, 14 nov. 1881; CN301-S292, 1886–1900; E53-S12, SS3/17; TP11, S1, SS20, SSS1, 13 oct. 1886, no.3688; 26 mars 1889, nos.4150–51; 23 juill. 1890, nos.4464–65; 13 nov. 1896, no.6036; 5 mai 1897, no.6073; 9 oct. 1897, no.6292; 20 avril 1918, no.339; janvier 1925, no.72. AVQ, P51, 1/1051-02; 2/1053-06; 4/1068-02. LAC, MG 26, G; MG 27, III, B4; MG 28, I 230. Qué., Bureau de la publicité des droits, Greffes, J.-É. Boily, 1886–1927; Joseph Sirois, 1925–34. Le Devoir, 28 mars 1930. L’Événement, 25 sept.–26 oct. 1906; 19 déc. 1911; 23 avril 1929; 29, 31 mars, 2, 4 avril 1930. Le Soleil, 7 déc. 1901; 28 sept.–25 oct. 1906; 29 mai, 19 déc. 1911; 18 janv. 1924; 28, 31 mars, 1er–3 avril 1930. Benjamin Demers, Une branche de la famille Amyot-Larpinière: M. Georges-Élie Amyot, manufacturier et brasseur de Québec, ses ancêtres directs et ses enfants (Québec, 1906). Les grands débats parlementaires, 1792–1922, Réal Bélanger et al., compil. (Sainte-Foy, Qué., 1994). Les ouvrières de Dominion Corset à Québec, 1886–1988, sous la dir. de Jean Du Berger et Jacques Mathieu (Sainte-Foy, 1993). Pierre Poulin, “Déclin portuaire et industrialisation: l’évolution de la bourgeoisie d’affaires de Québec à la fin du XIXe siècle et au début du XXe siècle” (mémoire de ma, univ. Laval, 1985); “Georges-Élie Amyot et la Dominion Corset,” Cap-aux-Diamants (Québec), 1 (1985–86), no.1: 9–12. Ronald Rudin, “A bank merger unlike the others: the establishment of the Banque Canadienne Nationale,” CHR, 61 (1980): 191–212; Banking en français: the French banks of Quebec, 1835–1925 (Toronto, 1985). Robert Rumilly, Henri Bourassa; la vie publique d’un grand Canadien (Montréal, 1953); Hist. de la prov. de Québec. B. L. Vigod, Taschereau, Jude Des Chênes, trad. (Sillery, Qué., 1996).

Bibliography for the revised version:

AVQ, P123.

Cite This Article

Marc Vallières, “AMYOT, GEORGES-ÉLIE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 16, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/amyot_georges_elie_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/amyot_georges_elie_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | Marc Vallières |

| Title of Article: | AMYOT, GEORGES-ÉLIE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2005 |

| Year of revision: | 2023 |

| Access Date: | December 16, 2025 |