Source: Link

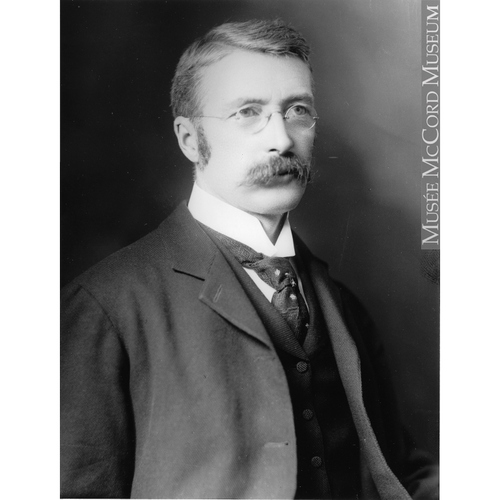

BELL-IRVING, HENRY OGLE, civil engineer, architect, businessman, politician, and imperialist; b. 26 Jan. 1856 near Lockerbie, Scotland, third of the seven children of Henry Bell-Irving and Williamina McBean; m. 11 Feb. 1886 Maria Isabella del Carmen Beattie (d. 1936) in Torquay, England, and they had four daughters and six sons; d. 19 Feb. 1931 in Vancouver.

Born into a Scottish family that traced its history to lands near the border with England that were granted to Richard Irving in 1549 and to the union of Irving and Bell family properties through marriage in the mid 18th century, Henry was raised to be proud both of being Scottish and of belonging to the British empire. Family members engaged in business in China, India, and South America, and his father, described in Henry Ogle’s will as a “merchant at Glasgow,” conducted trade in the West Indies. In the early 1860s a warehouse fire in Georgetown, British Guiana (Guyana), followed shortly by Henry Sr’s death, left Williamina a young widow with seven children and limited resources. She responded creatively by moving the family from Milkbank, their estate near Lockerbie, to Germany, where her sons could take advantage of the less costly education resulting from Chancellor Otto von Bismarck’s reforms. Young Henry left Merchiston Castle School in Edinburgh to attend the polytechnic school in Karlsruhe, where he trained as a civil engineer.

Educated and unsettled, Bell-Irving found work in Britain, but he soon realized that it would be difficult for him to make enough money to regain possession of Milkbank, which had been left to him but was burdened with debt. Responding to the Canadian Pacific Railway Company’s call for engineers, in 1882 he made a decision that would change his life: to work as a surveyor and engineer on the railroad’s westward construction crew pushing through the Selkirk and Rocky mountains.

In 1885, before the railway was completed, Bell-Irving quit, left the crew in the middle of British Columbia’s interior (probably near Revelstoke), and started making his way to the coast on foot. During his journey he was robbed by bandits, who took all of his valuables except his survey instruments. Henry continued walking until he reached Granville (Vancouver), where he found the business prospects exciting. He then travelled to southern England to marry Maria Isabella del Carmen Beattie, known as Bella, whom he had met some years earlier in Switzerland. She was the daughter of a Scot who owned a sugar plantation in Santiago de Cuba, where she had been born. Her family came from Dumfriesshire, like the Bell-Irvings, and was quite wealthy. After their wedding in 1886, the couple returned to the recently incorporated city of Vancouver, where both their family and their prosperity quickly increased. Bella gave birth to the first of ten children in 1887, with the next six arriving at intervals that averaged fifteen months.

Bell-Irving’s business initiatives first centred on architecture and real estate. After the great fire of June 1886, which destroyed most of the municipality, he used his engineering training to design some of the community’s early structures, such as the residence of Robert Garnett Tatlow* (his business partner during the late 1880s) and the commercial building that would be known as the Bell-Irving Block, both of which were completed in 1888. All of the city’s buildings attributed to him have been demolished.

In 1889 Bell-Irving’s business interests shifted to trade when he and a fellow Scot, Robert Horne Paterson, formed a shipping agency under the name of Bell-Irving and Paterson. They chartered the 897-ton clipper Titania to import gas and water piping, hardware, and liquor directly from Britain, and to export canned sockeye salmon in return. The immensely successful exploit illustrated the excellent prospects for investment in the fishing and salmon-canning industries, and they led Bell-Irving to organize two companies that would make him, by Vancouver standards, a rich man. By the fall of 1890 he had amassed enough capital from his family and friends in Britain to consolidate, at a cost of $366,000, nine west-coast canneries, seven of them on the Fraser River, into one firm, the London-based Anglo-British Columbia Packing Company Limited. Known as ABC Packers for short, it was incorporated on 13 April 1891. The London company was run by his cousin John Bell-Irving, the seventh laird of Whitehill, an estate near Lockerbie, while the Vancouver company co-owned by Henry Ogle and Paterson was appointed ABC Packers’ managing agent. In 1893 Bell-Irving dissolved his company and his partnership with Paterson and created H. Bell-Irving and Company (incorporated around 1901) to take the former’s place. Through this Vancouver-based agency he managed the assets of ABC Packers for commission fees of 2.5 per cent on purchases and 5 per cent on sales of the salmon pack. ABC Packers flourished, and for a period was the world’s top producer of sockeye salmon. Partly as a result of this success, at the start of the 20th century Bell-Irving had become concerned about the decline in the Fraser River fish stocks [see John Pease Babcock] and began to advocate a three-year moratorium on commercial sockeye fishing so that the stock could recover; however, both the government and his industry colleagues rejected the idea, and nothing came of it.

Despite the cyclical nature of the salmon-canning industry, indicated by Bell-Irving’s reference to “bloated profits” in 1912 and losses of up to $500,000 in the early 1920s, both the British investors and Bell-Irving himself profited handsomely from ABC Packers and H. Bell-Irving and Company Limited. Henry Doyle, an entrepreneur in the canning industry and amateur historian of the salmon-canning business, observed in 1924 that since its creation 33 years earlier, ABC Packers had paid out dividends of approximately $2 million to its shareholders, which was four times the amount of the company’s subscribed capital. The agency business was also lucrative; at Bell-Irving’s death in 1931, his estate, with a net value of $339,000, would rank 16th among the top 50 Vancouver fortunes of the period. He achieved this wealth despite the fact that he had already given away considerable, though undetermined, sums to help Great Britain and Canada fight World War I, and to support the families of his ten children.

Success in business, combined with the privileged social backgrounds of the Bell-Irvings and Beatties, had enabled Henry Ogle’s family to become leading members of early Vancouver high society. They owned several large houses, the most important of which, The Strands (where they lived for more than 20 years), had been designed by Bell-Irving and built in Vancouver’s fashionable West End between about 1907 and 1909. Henry and Bella had many servants, both British and Chinese, and hired governesses and tutors to teach their children, who were later sent to first-rate schools. They participated in status-defining rituals, making the round of afternoon visits known as at-homes, crossing the Atlantic frequently (Henry went annually to London), taking out memberships in elite clubs, and becoming involved with the most prestigious charities. In 1909 the patriarch even purchased Pasley Island, near Vancouver at the entrance to Howe Sound, for the recreational use of his family.

Bell-Irving considered himself a Scot and a Briton rather than a Canadian. His business ties exemplify the expansion of capital and influence from Britain to distant parts of the globe, including British Columbia. The imperial connection is illustrated by the head of ABC Packers, Henry’s cousin John, who at his death in 1927 was the chair of two companies trading in tea from Ceylon (Sri Lanka) in addition to the fish company in Britain. John had also been associated with the East India merchants Jardine, Matheson and Company, and had served on the Hong Kong Legislative Council. (The Jardines were related to the Bell-Irvings through marriage.)

British control of ABC Packers resulted in conservative investment practices. As Bell-Irving’s grandson Ian would note during an interview in 1982, the directors were primarily interested in dividends and the corporation’s image on the London Stock Exchange: “We were just another operation in the ‘Colonies’ to which none of them had ever been.” This emphasis on dividends, he argued, was a “continuing drain on [the company’s] resources [that] made for inadequate working capital and a subsequent lack of flexibility.” Its conservative investment practices may explain why ABC Packers went from controlling 25 per cent of the British Columbia salmon industry in the early 1890s to only 9 per cent in the mid 1920s. Henry’s loyalty to family, especially those who, according to him, had been “good enough” at the outset “to entrust [him] with their money,” and his ability to profit handsomely from commissions led him to persevere with the business despite the unresponsiveness of British directors to investment opportunities.

For the Bell-Irvings the reference points were London and the family homes at Milkbank and Torquay rather than Vancouver, at least until after World War I. Their ties to Britain were strong, and from 1903 to 1908 they had lived there. They purchased tweed suits, deerstalker hats, carpets, fabric, and furniture in London, even having the chintz coverings on chairs reglazed in the old country, and they subscribed to London-based publications such as the Daily Telegraph and the Times as well as the satirical magazine Punch. Henry and Bella sent their six sons to Loretto School in Musselburgh, Scotland, which was among the first rank of British private educational institutions in the last half of the 19th century. Their eldest daughter, Isabel, attended exclusive schools near London. The boys wore kilts for ceremonial family occasions and learned Scottish dancing. Henry served as president for two Scottish cultural associations in Vancouver: the St Andrew’s and Caledonian Society and the Vancouver Pipers’ Society. Even the salmon canned by ABC Packers was given a Scottish flair: Bell-Irving insisted on branding his product “Wee Scottie” (including the quotation marks), and the can labels featured an image of a young boy, in full Highland attire, riding a massive salmon as if it were a horse and holding up a tin in his hand with the tag line “Mon – he’s a gran’ Fish.” To show their loyalty to Britain, the Bell-Irving children stood on Vancouver’s railway platform and sang The soldiers of the queen for the first contingent of troops to depart for the South African War. As Isabel pointed out years later, “In our generation we were not unhappy to be a colony of Britain.”

Bell-Irving had engaged in a brief career as a politician in Vancouver and acted as a representative of its business community. He served as a city alderman and chairman of the Board of Works in 1887 and 1888. Seven years later he sat for two terms as president of the Vancouver Board of Trade. He would frequently represent the board at international conferences, such as the Fifth Congress of Chambers of Commerce of the Empire, held in Montreal in 1903.

Bell-Irving’s view of the world is evident in his enthusiastic support for British imperialism. After his time as alderman he participated in politics mainly for causes that promoted Britain. He had unlimited enthusiasm for imperial federation, and one of the reasons for moving his family to England in 1903 was to join colonial secretary Joseph Chamberlain’s campaign for the creation of an imperial tariff and an end to British free trade. He fought to have the Canadian government support the imperial navy rather than create its own, and in 1910 he organized a large public meeting in Vancouver to urge Canada to help Britain build Dreadnoughts [see Sir Robert Laird Borden; Sir Wilfrid Laurier*]. He was also instrumental in the formation of Vancouver’s 72nd Regiment (Highlanders) in 1910, which became known as the Seaforth Highlanders of Canada in 1912.

Yet nothing excited the patriotic ardour of Bell-Irving and his family like the outbreak of war in 1914. All six of his sons enlisted, and two of his daughters served as nurses. His boys won numerous citations for bravery and were often injured; one, Roderick Ogle*, was killed only weeks before the war’s conclusion. Henry had financially supported the purchase of machine guns and revelled in public acknowledgement of his status as “the father of a famous fighting family.” He also donated a large quantity of canned salmon for the war effort; as a result, his “Wee Scottie” salmon became linked with British patriotism and imperialism, an association that was promoted by ABC Packers. In 1917 he and another Vancouver imperialist, Sir Charles Tupper*, led the call for conscription and encouraged the formation of a non-partisan government to manage Canada’s war effort. Many western Canadian Liberals were offended when Bell-Irving publicly labelled them “traitors” and “friends of the Kaiser” for opposing what would become the Union government.

As a capitalist and imperialist who believed in the superiority of all things British, Bell-Irving viewed Asian workers in the province as little more than racially inferior economic factors of production. Hostile to all forms of organized labour, he played a major role in breaking strikes by Fraser River sockeye fishermen in 1893 and 1900 [see Frank Rogers*], and he employed Asian workers to drive down wages. The Chinese, he asserted publicly in 1891, “are less trouble and less expensive than whites.… I look upon them as steam engines or any other machine.” His attitudes about race reflected characteristic thinking of the period among Anglo-Canadians but were clearly also shaped by class interests. Interestingly, he and his wife developed a close, though paternalistic, relationship with their Chinese servants, such as Mah Sing, who served the Bell-Irvings for many years.

Bell-Irving had a talent for sketching, and as a young man he had made watercolour paintings of the Rockies. This gentler side of his personality was less conspicuous than his attitude towards masculinity, which, like his business ties and politics, reflected the influence of British imperialism. He viewed military values as essential features of manhood, qualities that he sought in the education of his sons at Loretto, where the headmaster, Hely Hutchinson Almond, believed that athleticism forged character more powerfully than book learning. He kept himself in excellent shape, and was a superb hunter and skater. He was instrumental in the creation of the Connaught Skating Club, established in 1911, the first of its kind in British Columbia, and served for at least five years as its president. He climbed mountains when time and circumstance permitted, and lifting dumb-bells was part of his daily exercise. His emphasis on athleticism and strength left little room for physical weakness. As Isabel stated, “Daddy was never understanding of illness.” This insensitivity distanced him from his wife, who, by the time she gave birth to her tenth child at the age of 42, was suffering from rheumatoid arthritis and could barely walk. Bella spent much of the rest of her life (more than 30 years) attended by nurses; according to Ian, his grandfather increasingly “kept busy not staying at home.”

In March 1930, soon after his 74th birthday, Henry Ogle Bell-Irving gathered some of his grandchildren and in their company climbed Grouse Mountain, on Burrard Inlet’s north shore, to ski. When he died 11 months later, the victim of cancer, he was remembered as a successful businessman, a strong imperialist, and the founder of a notable British Columbian family. His career illustrates the exceptional importance of the British connection in shaping the early settlement history of the province.

The author conducted interviews at various times in 1997 and 2000 with Henry Ogle Bell-Irving’s granddaughters Elizabeth O’Kiely and Verity Sweeny Purdy and his grandsons the Honourable Henry Pybus Bell-Irving and Ian Bell-Irving. The author also consulted Bell-Irving family material collected by Elizabeth O’Kiely, including notes taken during her interview with Henry Ogle’s daughter Isabel Sweeny in the early 1970s.

BCA, GR-1415.1695. City of Vancouver Arch., AM1 (Bell-Irving family coll.). Daily News-Advertiser (Vancouver), 5 May 1891. The development of the Pacific salmon-canning industry: a grown man’s game, ed. Dianne Newell (Montreal and Kingston, Ont., 1989), 205–6. Henry Doyle, “Rise and decline of the Pacific salmon fisheries” (typescript, North Hollywood, Calif., 1957; copy available at Univ. of B.C. Library, Rare Books and Special Coll., Vancouver). Douglas Harkness, “The Canadian Bell-Irvings” (typescript, n.p., n.d.; in possession of Elizabeth O’Kiely, West Vancouver, B.C.). R. G. Hill, “Biographical dictionary of architects in Canada, 1800–1950”: dictionaryofarchitectsincanada.org (consulted 10 Jan. 2018). R. A. J. McDonald, “‘He thought he was the boss of everything’: masculinity and power in a Vancouver family,” BC Studies (Vancouver), no.132 (winter 2001–2): 5–30; Making Vancouver: class, status, and social boundaries, 1863–1913 (Vancouver, 1996). Bernard McEvoy and A. H. Finlay, History of the 72nd Canadian Infantry Battalion, Seaforth Highlanders of Canada (Vancouver, 1920). Pacific Fisherman (Los Angeles), 50, no.9 (August 1952, 50th anniversary no.). H. K. Ralston, “The 1900 strike of Fraser River sockeye salmon fishermen” (ma thesis, Univ. of B.C., 1965). M. E. Vance, “‘Mon – he’s a gran’ fish’: Scots in British Columbia’s interwar fishing industry,” BC Studies, no.158 (summer 2008): 32–61.

Cite This Article

Robert A. J. McDonald, “BELL-IRVING, HENRY OGLE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 8, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/bell_irving_henry_ogle_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/bell_irving_henry_ogle_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Robert A. J. McDonald |

| Title of Article: | BELL-IRVING, HENRY OGLE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2020 |

| Year of revision: | 2020 |

| Access Date: | March 8, 2026 |