Source: Link

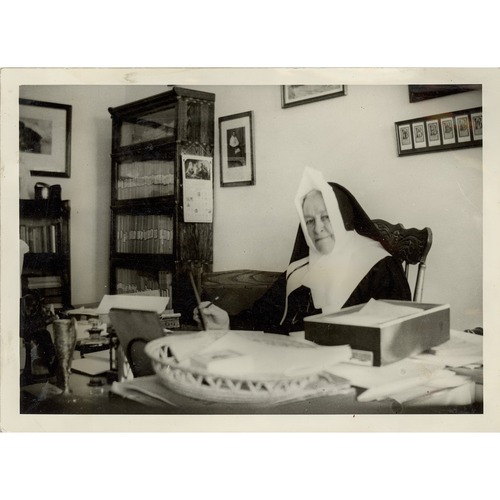

BENGLE, MARIE-AVELINE, named Sainte-Anne-Marie, member of the Congregation of Notre-Dame, teacher, school administrator, and schools founder; b. 15 Oct. 1861 in Saint-Paul-d’Abbotsford, Lower Canada, daughter of Guillaume Bengle, a farmer, and Philomène Pion; d. 13 March 1937 in Montreal.

After attending the parish school, Marie-Aveline Bengle pursued her studies in Sherbrooke from 1875 to 1880 at Mont-Notre-Dame of the Congregation of Notre-Dame, where she was a boarder. Her maternal aunt, Sister Sainte-Luce, was its mother superior. In February 1880 Marie-Aveline achieved her model-school teaching certificate, the highest diploma for the period. Once back with her family, following the example of her aunt, she decided to apply for admission to the noviciate of the Congregation of Notre-Dame in Montreal. She took her religious vows on 14 Sept. 1882, adopting the name Sister Sainte-Anne-Marie. Appointed a teaching sister in January 1883 at the Pensionnat Mont-Sainte-Marie, a prestigious establishment in Montreal, she assumed responsibility for the courses of the top class with the most advanced students, known as “graduates,” in September 1884. Through her pedagogical initiatives (incorporating the use of a herbarium and a geological collection into her lessons and delivering inspired lectures), her talent for composing prose and verse that enlivened the planning of festive occasions, and her skill in securing donations to finance the library and the physics room, she enjoyed unrivalled admiration from her pupils and her fellow nuns. Having become the mother superior’s assistant in 1897, she decided to organize advanced classes at Mont-Sainte-Marie for the “graduate” pupils and the nuns of Montreal to better prepare the teaching sisters for their work. She worked in collaboration with professors from the Université Laval in Montreal, and courses in literature, philosophy, Latin, and science were introduced. She was appointed mother superior of the boarding school in 1903.

In 1904 the Congregation of Notre-Dame tried, unsuccessfully, to set up a post-secondary program, an attempt that failed because the Roman Catholic committee of the Council of Public Instruction ruled, as the congregation’s historian relates, “that it [was] not appropriate to ‘thrust girls into higher education.’” On the other hand, as reported in the congregation’s archives, Marie Gérin-Lajoie [Lacoste*], founder of the Fédération Nationale Saint-Jean-Baptiste, urged the nuns to establish “a centre of higher learning for girls … the laity,” she said, “will overtake you!” She threatened to send her own daughter, Marie*, to study at McGill University.

This situation changed, however, with the announcement in 1908 of the opening of a secular and non-denominational high school for girls. It was the initiative of two journalists, Éva Côté [Circé*] and Georgine Gill [Bélanger*], known as Gaétane de Montreuil, who would succeed in keeping their school running for two years. Those in charge of the congregation then returned to the plan they had developed four years earlier and instructed Sister Sainte-Anne-Marie and Sister Sainte-Sophronie to take the needed steps: securing the patronage of Archbishop Paul Bruchési, negotiating with the Université Laval in Quebec City and in Montreal, and hiring teachers. Despite the obstacles it was decided to proceed without delay and to open the school by autumn 1908 on the very premises of the brand-new mother house in order to thwart the plans of another congregation, the Sisters of the Holy Names of Jesus and Mary, which also wanted to affiliate one of its boarding schools to the university. Sister Sainte-Anne-Marie was deeply convinced that “if women’s higher education belongs to anyone in Montreal, it is to the Congregation of Notre-Dame and to no other!” Besides the necessary authorizations, she obtained for the École d’Enseignement Supérieur pour les Jeunes Filles the exclusive right to provide higher education to girls for 25 years. The institution, of which Sister Sainte-Anne-Marie was to be the principal until her death, provided the last four years of classical education in French and English. Greek studies would not be offered to girls until 1922; in the meantime, they could choose to learn Spanish, Italian, or German. The English department opened under the name of Notre Dame Collegiate Institute, which became Notre Dame Ladies College in 1909, and was run by Sister Sainte-Agnès-Romaine. That year, in a strategic move, the business course, which had been given at the École Saint-Charles since 1905, was transferred to the mother house for integration into the École d’Enseignement Supérieur. This unilingual (English) department – enjoying the highest enrolment of all programs and to be known as Mother House – ensured the survival of the school. In fact, for the first 25 years, there were few students at the École d’Enseignement Supérieur, even fewer who had completed the course work for the baccalauréat, and a third of those who had were sisters belonging to the Congregation of Notre-Dame and several other congregations. The first to obtain a baccalauréat was Marie Gérin-Lajoie in 1911. Teachers, most of whom were laity, were paid five dollars an hour and continued to give classes even after the nuns were in a position to teach. During the early years the nuns attended classes and served as tutors for their pupils, and were thus able to take the exams at the same time as their charges.

In 1913 Sister Sainte-Anne-Marie was also appointed mistress in charge of studies, one of her congregation’s biggest responsibilities. In 1916, along with the other Montreal congregations, she obtained from the Université de Montréal official sanction for the arts and sciences course, a program equivalent to the first four years of classical education, but it focused on a broad range of subjects rather than on Greek and Latin. This move ensured that there would be a pool of students inclined to turn towards the École d’Enseignement Supérieur. In 1917 she insisted that the nuns be able to study Greek, and in 1920 demanded the same for the students to put them on a par with schoolboys.

Sister Sainte-Anne-Marie also had to equip herself with the diplomas required for her particular role as principal of the École d’Enseignement Supérieur. In 1913 she had received special permission to take a degree in philosophy by presenting a work on socialism. In 1915 she graduated, receiving the following citation: “Sister Sainte-Anne-Marie, Bachelor of Arts, student of the École Supérieure pour Jeunes Filles.”

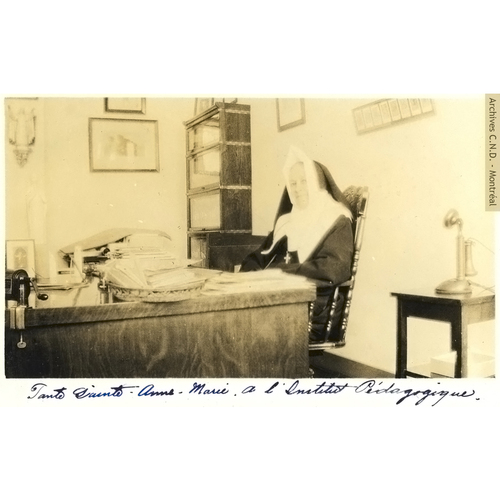

Next, she considered offering the teaching nuns courses to upgrade their qualifications. She made numerous approaches to the provincial secretary, Louis-Athanase David*, and in 1924, by means of the Act respecting the establishment of a pedagogical institute at Montreal, obtained a government grant of $25,000 for 15 years to “establish and … maintain a teaching institute or a superior normal school, for further training of women teaching personnel, both religious and lay.” It was to offer, in French, a matriculation diploma, a ba, and a doctorate in pedagogy, which would be conferred by the Université de Montréal.

In December 1925, while the Institut Pédagogique was under construction, Sister Sainte-Anne-Marie, with her companion Sister Sainte-Eliza, made a study trip to Europe to visit Catholic teaching institutions. She also took the opportunity to further the case for beatification of her congregation’s founder, Marguerite Bourgeoys*. A voluminous correspondence describes this journey from which she returned in July with two convictions: nuns must be equipped with advanced degrees, and they must offer the best programs to girls in order to counter any lay undertaking that might lapse into feminism. Nonetheless, her stance was paradoxical. She demanded that the course of study offered to girls for the matriculation diploma be identical in all respects to that offered to boys, but in 1924 she deplored the fact that one of her students who had attained the diploma, Marthe Pelland, was going on to study medicine.

In 1926 the École d’Enseignement Supérieur pour les Jeunes Filles (the École d’Enseignement Secondaire from 1922) moved to the Institut Pédagogique, which opened its doors on 29 September, and was henceforth called the Collège Marguerite-Bourgeoys. The commerce department – which then took the name Notre Dame Ladies College – nevertheless remained at the mother house as a private school, and became the most highly rated business college in Montreal. Since the Collège Marguerite-Bourgeoys was established within a heavily subsidized institution, its financial survival was assured.

After her travels Sister Sainte-Anne-Marie worked unceasingly to organize and structure new initiatives at the Institut Pédagogique (of which she was to be the principal until her death) that would compensate for the small number (about 30) studying for a degree in pedagogy. The École Normale de Musique opened in 1926. The following year she instituted lectures and summer-school courses for teaching nuns and lay instructors to which hundreds flocked, and introduced training programs for teachers of art and drawing. The École de Chant Liturgique followed in 1928. She also worked to set up a program to train teachers of disabled children. It was at the Institut Pédagogique that Sister Marie Gérin-Lajoie opened, in 1931, her school of social action, precursor to the social-services program at the Université de Montréal. Sister Sainte-Anne-Marie knew how to surround herself with competent nuns, and it is certain that “her” classical college could not have prospered without the work and talent of her colleague, Sister Sainte-Théophanie, whom she called in her correspondence “my dear Graziella, my sister, my daughter, my friend.”

As principal of the Institut Pédagogique, Sister Sainte-Anne-Marie was appointed ex officio in 1928 to the pedagogical commission of the Montreal Catholic School Commission; she was its first woman member. She thus found herself at the heart of an organization that played a pioneering role in developing public education. From September 1930 to January 1931 she again travelled in Europe, this time in the company of the superior general of the Congregation of Notre-Dame, Mother Sainte-Marie du Cénacle. The correspondence relating to the journey reveals that on this trip the cause of the beatification of Marguerite Bourgeoys was as important as the teaching visits. The golden jubilee of Sister Sainte-Anne-Marie, in 1932, was the occasion for memorable celebrations. The Université de Montréal awarded her an honorary doctorate in pedagogy, one of the numerous distinctions this exceptional educator was to receive.

Once the institutions of her congregation were well established, Sister Sainte-Anne-Marie extended her influence to other congregations. In 1932 she permitted a few pupils of the Sisters of St Anne to sit the university examinations in rhetoric as extramural students, along with many nuns of the other congregations who took advantage of this concession. However, this strategy ran the risk of encouraging the other congregations to imitate the Congregation of Notre-Dame. Moreover, since the status of the Congregation of Notre-Dame as the sole institute providing higher education for women would come to an end the following year, the heads of the congregations managed to wrest permission from the bishop. By 1933 the creation of two new colleges was authorized in Montreal on condition that the students would take their exams at the Collège Marguerite-Bourgeoys.

In 1936 Sister Sainte-Anne-Marie informed the pedagogical commission that the Catholic committee of the Council of Public Instruction wanted to shut down the Catholic Central Board of Examiners, which awarded teaching certificates to boarding-school pupils and to the many nuns who had not attended a normal school. In April she organized an extraordinary meeting at the Institut Pédagogique with the heads of study of all the teaching congregations; she informed them that they would be allowed to establish scholasticates, or normal schools for young nuns, and she negotiated a two-year postponement of the closing of the board. The following years (three, in fact) were therefore put to use by the congregations to train the personnel they required at the Institut Pédagogique, to establish scholasticates, and to open new normal schools. According to the director general of studies of the Filles de la Charité du Sacré-Cœur de Jésus, who relayed to her nuns the proposals of Sister Sainte-Anne-Marie, the latter had declared, “It will be an advantage, because [this measure] will uphold the predominance of religious institutions over lay institutions.” Such predominance had really been her goal for more than 50 years.

On 28 Feb. 1937 Sister Sainte-Anne-Marie was taken to the mother house suffering from a form of poisoning. She died on 13 March, giving rise to a remarkable outpouring of testimonials and tributes from all quarters; these were compiled the following year in Montreal in a publication, Mère Sainte-Anne-Marie, c.n.d., in honour of the woman who had been the most famous nun of the Congregation of Notre-Dame. In seeking above all to develop the competence and excellence of teaching nuns, she found herself in a position to contribute in an exceptional way to promoting education for women. By establishing institutions for girls, she was able to achieve her goal.

Sister Sainte-Anne-Marie’s album of travel correspondence, principally letters to her sister, Sister Sainte-Anne d’Auray, also a member of the Congrégation de Notre-Dame, can be found in the private arch. of Gilles Bengle (Montreal). In the Arch. of the Congrégation de Notre-Dame (Montreal), the following sources were consulted: the file on the founding of the Collège Marguerite-Bourgeoys, the account book of the École d’Enseignement Supérieur pour les Jeunes Filles, the directories of the Instit. Pédagogique and the École d’Enseignement Supérieur pour les Jeunes Filles (308.600); the file on the founding of the Instit. Pédagogique (308.601); the diplomas received by Marie-Aveline Bengle (under her birth-name and her name in religion) (308.604); the correspondence of Sister Sainte-Anne-Marie and Sister Sainte-Eliza during their trip to Europe, in two volumes (1925–26) (308.604); letters received by Sister Sainte-Anne-Marie when she obtained her awards (450.250); the correspondence of Sister Sainte-Anne-Marie and Mother Sainte-Marie du Cénacle during their trip to Europe, in two volumes (1930–31) (450.250 and 565.100); and the correspondence of Sister Sainte-Anne-Marie with Mgr Paul Bruchési (including the letters sent to the archbishop) (451.250 and 560.000).

Arch. des Filles de la Charité du Sacré-Cœur de Jésus (Sherbrooke, Québec), Lettre de sœur Thérèse-Marie, directrice générale des études des Filles de la charité du Sacré-Cœur de Jésus, à ses religieuses, 8 avril 1936. BANQ-CAM, CE602-S23, 16 oct. 1861. Le Devoir, 15, 16, 17 mars 1937. La Patrie, 25 avril 1908. [D.‑A. Lemire-Marsolais, dite Sainte-Henriette, et] Thérèse Lambert, dite Sainte-Marie-Médiatrice, Histoire de la Congrégation de Notre-Dame (11v. en 13 parus, Montréal, 1941– ), 11. M.‑P. Malouin, Entre le rêve et la réalité: Marie Gérin-Lajoie et l’histoire du Bon-Conseil (Saint-Laurent [Montréal], 1998). Lucienne Plante, “L’enseignement classique chez les sœurs de la Congrégation de Notre-Dame, 1908–1971” (thèse de phd, univ. Laval, 1971); “La fondation de l’enseignement classique féminin au Québec, 1908–1926” (mémoire de d.e.s., univ. Laval, 1967). A.‑M. Sicotte, Marie Gérin-Lajoie, conquérante de la liberté (Montréal, 2005).

Cite This Article

Micheline Dumont, “BENGLE, MARIE-AVELINE, named Sainte-Anne-Marie,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 1, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/bengle_marie_aveline_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/bengle_marie_aveline_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Micheline Dumont |

| Title of Article: | BENGLE, MARIE-AVELINE, named Sainte-Anne-Marie |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2018 |

| Year of revision: | 2018 |

| Access Date: | March 1, 2026 |