BERNARD, SUSAN AGNES (Macdonald, Baroness Macdonald), politician’s wife; b. 24 Aug. 1836 at Bernard Lodge, south of Spanish Town, Jamaica, fifth child and only daughter of Thomas James Bernard, a sugar plantation owner, and Theodora Foulkes Hewitt; m. 16 Feb. 1867 John A. Macdonald*, and they had a daughter; d. 5 Sept. 1920 in Eastbourne, Sussex, England.

The Bernard family fortunes, weakened by the imperial emancipation of slaves in 1833, were further wasted by the death of Thomas Bernard in 1850 in the cholera epidemic that took about eight per cent of the Jamaican population. The island was no longer promising to the widow Bernard and her family. Theodora and Agnes left in 1851 for England; Hewitt Bernard*, the eldest son, left six months later for the Province of Canada. In 1854 Agnes and her mother joined him in Barrie, Upper Canada.

In 1858 Hewitt became private secretary to John A. Macdonald, attorney general for Upper Canada, and Agnes and Mrs Bernard moved with Hewitt to Toronto. They followed him to Quebec City, the new provincial capital, in 1859. Agnes met Macdonald there the next year. When the government moved to Ottawa in 1865, few wanted to transfer but Hewitt, then Macdonald’s deputy, had to. On his advice, Agnes and her mother went to England, living mostly in London. That was where Macdonald met Agnes again, in 1866, at the time of the London conference on British North American union. When Macdonald approached Hewitt about marrying his sister, Hewitt had only one objection, Macdonald’s drinking habits. Macdonald replied that he would reform. Certainly Agnes knew about the problem before she married him at St George’s Church, Hanover Square, in London in 1867.

Following confederation and her husband’s knighthood, she set up housekeeping in Ottawa as Lady Macdonald. She was an earnest young woman, with a temper and not much ability to laugh when things went wrong. High-minded and vigorous, she had to learn to share her husband with his political life, and she cast a critical eye on some of it. “How hard it is to know how to do right! I know I am very apt to be led astray by motives . . . ,” she reflected, “and I also know that my love of power is strong.” “Strong” gets Agnes right. She was bold, sometimes imprudent, and she was intensely curious about the world around her. She was not easily intimidated, except perhaps by society; she was ill at ease as a hostess, and such social duties as became a prime minister’s wife did not come easily to her.

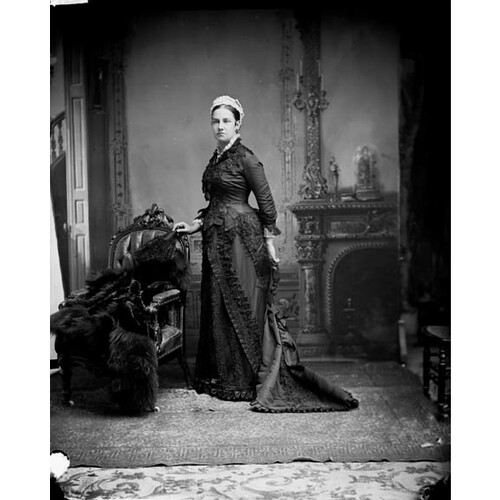

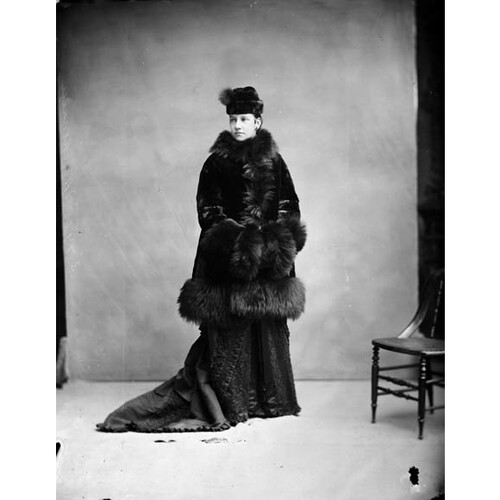

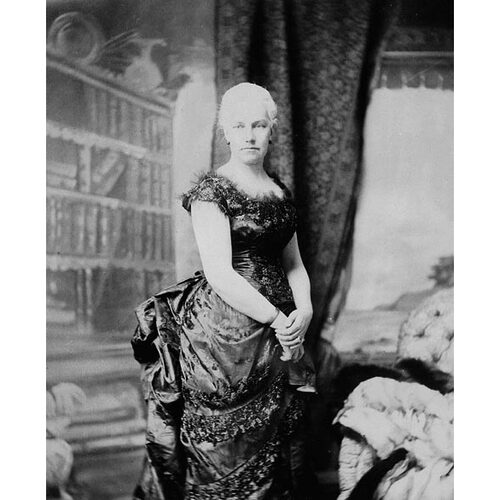

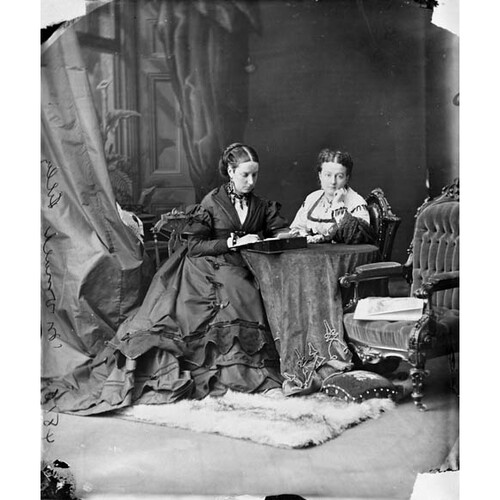

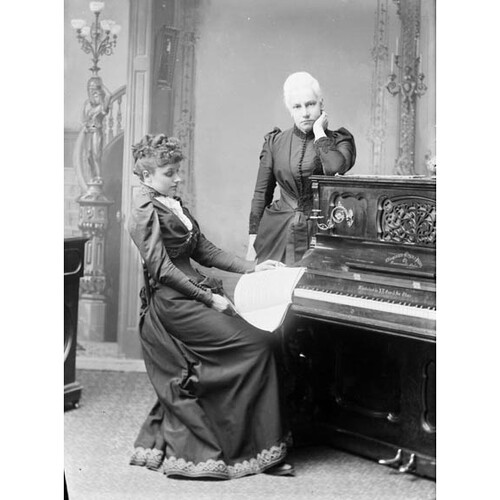

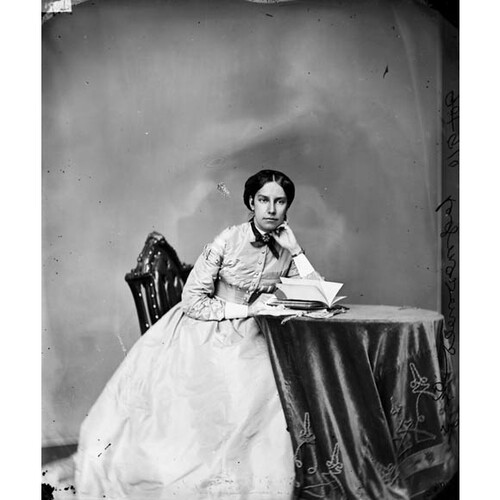

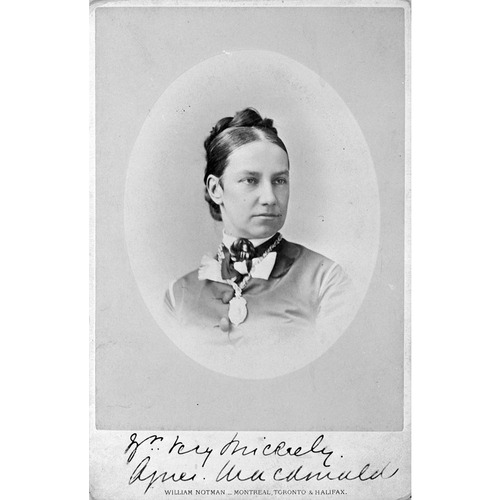

When her husband failed to reform quite as promised and took to the bottle every so often, she took to religion and asceticism. She would need both. Macdonald was penniless in 1869 and in February of that year Agnes gave birth to Margaret Mary Theodora. Within three months it was clear that Mary had water on the brain, that is, she was hydrocephalic and would never be normal. She would never run or talk or play as other children did, or even look after herself. What that condition must have cost Agnes and her husband no one can ever know. Agnes needed the consolations of St Alban the Martyr Anglican Church. “Disappointment” was the word she used in her diary about Mary, but that masked “one of the saddest times in my life.” She asked God to let her learn cheerfully the lessons of humility and sacrifice that Mary’s birth and life must teach. Intimations of the effect are evident in photographs of Agnes done in 1868 and in 1878. The juxtaposition is startling.

When Macdonald became leader of the opposition in 1873, he had only $2,500 or so annual income from the Testimonial Fund put together for him by friends. He needed more and in 1875 he migrated to Toronto with his family to develop his law practice. His drinking would break out from time to time. The only person who could do anything with him, said Charles Belford* of the Toronto Mail, was Lady Macdonald, but even she was not always capable of handling him. When Macdonald was sober, which was most of the time, he tried to gratify her wishes. What he would not do, even to please her, was allow her influence in public decisions.

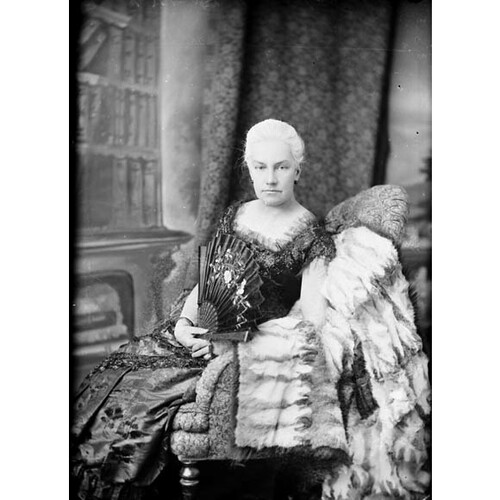

In 1878, after Sir John had returned to power, the Macdonalds moved back to Ottawa, where, in the opinion of Lady Aberdeen [Marjoribanks*], Agnes came to rule society “with a rod of iron.” Lady Macdonald was not easy to approach; she lacked the graces and kindnesses of small talk. Rather, she was apt to present herself in the opposite mode, a starchy austerity. After ten years of Mary and having to struggle occasionally with her husband’s drinking, such hardening of her demeanour was perhaps understandable. In 1882 the Macdonalds bought a summer home in Quebec near Rivière-du-Loup, Les Rochers, and a new residence in Ottawa, Earnscliffe, which they occupied a year later.

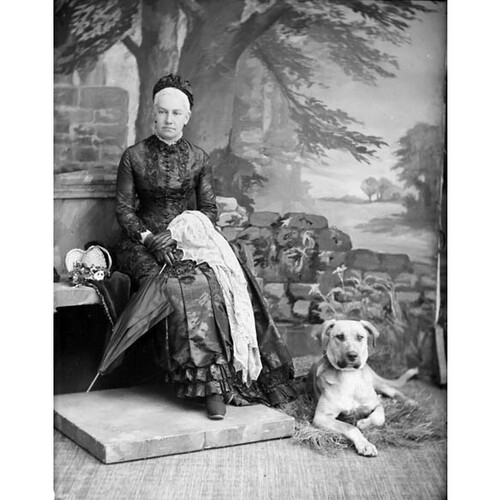

A month after Macdonald’s death in June 1891, Agnes became Baroness Macdonald of Earnscliffe in her own right. Undoubtedly recommended by Governor General Lord Stanley*, her elevation to the peerage was a tribute to her husband more than to her. It might have been wise to resist it. Macdonald’s estate was adequate but it could barely stand the social costs of her peerage and the strain of her having to look after Mary. She and Mary found Earnscliffe impossible; there were too many memories. She began a life of wandering: Banff (Alta), where the family had a cottage, the west coast, and with Hewitt in Lakewood, N.J. After Hewitt’s death in 1893, Agnes and Mary went to live in England, taking a house in Sydenham in southeast London. But the wet and gloomy English winter drove them to spend winters in Italy. She sold Les Rochers in 1895 and Earnscliffe in 1900. By 1905 she had taken to the motor car; though she seems not to have owned one, she enjoyed those of friends. She loved to drive in Scotland, “tearing about – thro’ the most beautiful glens in the very best Mercedes motor!” The image reminds one of her delight in riding on the cowcatcher of the train crossing through the Rockies in 1886. One of her last links to Canada was Joseph Pope*, Sir John A.’s former secretary and an important executor of his estate, but she broke with him in 1913 over the transfer of the estate to the Royal Trust Company.

Agnes died of a stroke in 1920 at Eastbourne, on the south coast of England. Mary would live on until 1933. In Agnes’s years of widowhood, she had lived without much joy in her peripatetic existence. As she wrote to Pope in 1897, “I am in truth only a very sad old woman – with a past, alas! wholly unforgotten & unforgettable!”

[The Sir John A. Macdonald papers at NA, MG 26, A, are empty of correspondence between Macdonald and Agnes. The suspicion is that she destroyed her own letters to her husband and his to her. Her diary of 1867–75 has survived (vol.559A), one presumes under her nihil obstat. There is some material on her in the T. C. Patteson papers at the AO (F 1191).

Agnes Macdonald published several accounts of her travels and observations on Canadian life in Murray’s Magazine (London): “By car and by cowcatcher,” “On a Canadian salmon stream,” and “On a toboggan,” 1 (January–June 1887): 215–35, 296–311; 2 (July–December 1887): 447–61, 621–36; and 3 (January–June 1888): 77–86. Another travel account, “An unconventional holiday,” appeared in the Ladies’ Home Journal (Philadelphia), 8 (1890–91), no.9: 1–2 and no.10: 1–2.

Louise Reynolds, Agnes: the biography of Lady Macdonald (Toronto and Sarasota, Fla, 1979), is comprehensive but generally uncritical. Sandra Gwyn, The private capital: ambition and love in the age of Macdonald and Laurier (Toronto, 1984), and Heather Robertson, More than a rose: prime ministers, wives and other women (Toronto, 1991), offer discussions of Agnes that are more perceptive. p.b.w.]

Cite This Article

P. B. Waite, “BERNARD, SUSAN AGNES (Macdonald) (Baroness Macdonald, Lady Macdonald),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 1, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/bernard_susan_agnes_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/bernard_susan_agnes_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | P. B. Waite |

| Title of Article: | BERNARD, SUSAN AGNES (Macdonald) (Baroness Macdonald, Lady Macdonald) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1998 |

| Year of revision: | 1998 |

| Access Date: | March 1, 2026 |