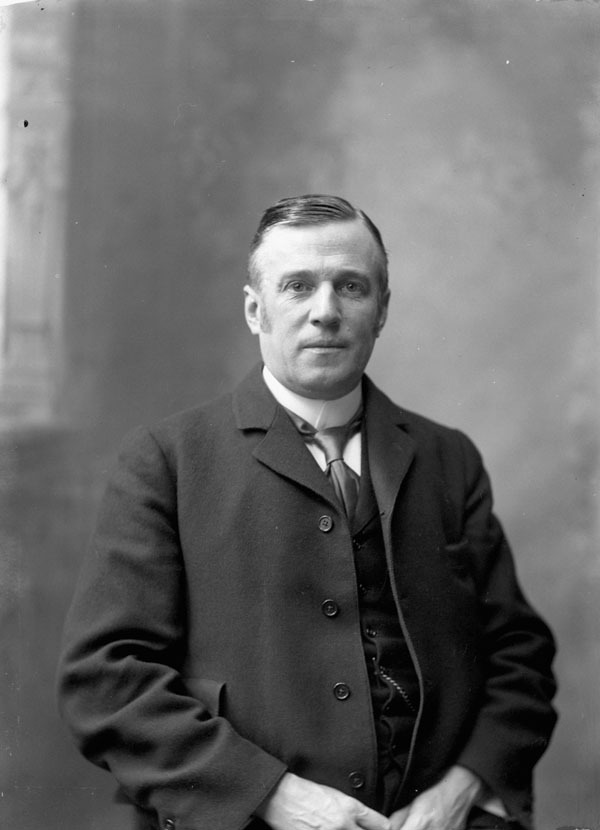

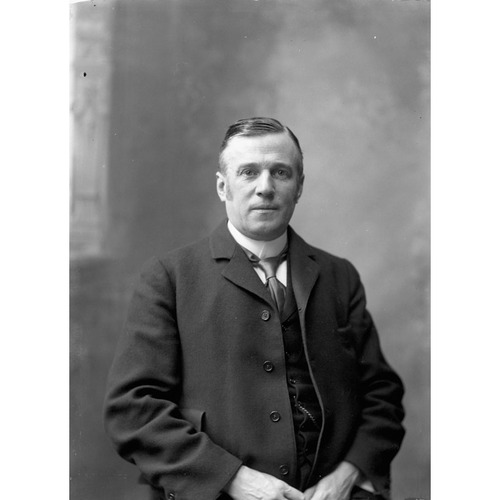

POPE, Sir JOSEPH, clerk, private secretary, civil servant, and author; b. 16 Aug. 1854 in Charlottetown, elder son of William Henry Pope* and Helen DesBrisay; m. 15 Oct. 1884 Marie-Louise-Joséphine-Henriette (Minette) Taschereau in Rivière-du-Loup, Que., and they had five sons and a daughter; d. 2 Dec. 1926 in Ottawa.

The family of W. H. Pope had a pleasant house and grounds a mile out of Charlottetown. Most families of his standing sent their children to England to be educated; Joseph went to Prince of Wales College, a local grammar school. When he was ten his father took him on board the Queen Victoria to meet the Canadian delegates to the Charlottetown conference. W. H. Pope lived in the style of the upper-middle-class gentry but without the income for it; when he died suddenly in 1879, he left his family largely unprovided for.

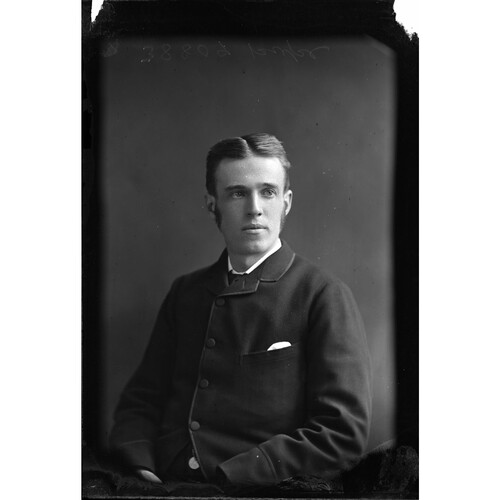

A slight, delicate youth not much given to sports, Joseph had been put to work in 1870 as a clerk for Prince Edward Island’s treasurer, his grandfather Joseph Pope*. With no experience and atrocious handwriting, he took steps to improve himself. He was good at mathematics and would always have a penchant for astronomy. Through his father he managed in 1872 to get a clerkship in the Merchants’ Bank of Canada in Montreal; by 1878 he was working in the Bank of Nova Scotia in Halifax.

After the Conservative victory in the federal election of 1878, his uncle James Colledge Pope* became Sir John A. Macdonald*’s minister of marine and fisheries, and the young nephew became the minister’s private secretary. Joseph then set to work to learn Pitman shorthand. He needed it. After his father’s death, half of his income went to support his mother and sisters. His uncle retired in July 1882 owing to ill health, and Joseph’s friend Frederick White, Macdonald’s private secretary and controller of the North-West Mounted Police, found he had too much to do. He recommended Pope to the prime minister. By September Pope had largely taken over White’s secretarial responsibilities. All Macdonald’s letters had to be done by hand: although typewriters were coming in, Macdonald would not sign a typed letter unless of the most formal character, and then only when he could not avoid it.

Pope’s real education in the great world thus began. He had lived in a boarding house on $20 a month, unable to afford the role of a man about town. Now, however, as the prime minister’s private secretary, he became something of a personage. Macdonald treated him with great kindness. As early as July 1883 he wrote Pope from his summer home, Les Rochers, in Rivière-du-Loup, “My wife and her brother are off on a spree to Halifax. I wish you were here to keep me company.” Each summer from then on Pope was part of Macdonald’s entourage. It was in Rivière-du-Loup that Pope met Minette Taschereau, eldest daughter of justice Henri-Thomas Taschereau*, whose wife was a Pacaud from Arthabaskaville (Arthabaska), Que., Wilfrid Laurier*’s stamping ground. Pope’s long and close acquaintance with the Lauriers followed. After Laurier became leader of the Liberal opposition in Ottawa in 1887, Lady Macdonald [Susan Agnes Bernard*] was not sure that this relationship should be encouraged, but then she was always more partisan than her husband. Macdonald himself was firm in Pope’s defence, having established in his own mind Pope’s integrity and discretion. He was glad that Pope had such a friend as the Liberal leader. “Laurier will look after you should you need a friend when I am gone,” he told his secretary. On 29 Nov. 1889 Macdonald appointed Pope assistant clerk of the Privy Council, which brought a substantial increase in salary; he would retain this office until 1896. For his part he found the work rich and rewarding, and he loved Macdonald. When Macdonald died in 1891 Pope mourned as for a father.

With Hugh John Macdonald, Edgar Dewdney*, and Fred White, Pope was a trustee of Macdonald’s estate. As the youngest and most vigorous of the group, and the closest to Lady (now Baroness) Macdonald, he became her indispensable guide and financial adviser. She supported his writing her husband’s biography and made available to him all correspondence except what was personal to her. She gave him carte blanche as to what he should pen, though in November 1892 she felt constrained to warn him to be careful in writing of Macdonald’s political colleague Sir Charles Tupper*. Pope probably did not need the advice: with him the diplomat usually triumphed over the historian. Care, caution, and discretion had always been Pope’s strength, and his weakness.

It was the same in his capacity as the effective manager among the trustees of Agnes’s financial affairs. Though not badly off, she travelled constantly and worried about money. This uneasiness was the reason for her eventual falling out with Pope. By 1900 she thought her money might be administered more aggressively by a trust company. Pope maintained that Macdonald’s arrangements for his widow should be left to stand, so he dragged his feet. The transfer of Agnes’s funds to the Royal Trust Company was eventually concluded in 1914 but by that time the breach between Agnes and Pope had become too wide to bridge.

As assistant clerk of the Privy Council, Pope had begun to work with Canadian state papers, in particular those relating to the Bering Sea arbitration between Canada and the United States that took place in Paris in 1893. Technically he was there as secretary to fisheries minister Charles Hibbert Tupper, the appointed British agent. Also there, as an arbitrator, was Prime Minister Sir John Sparrow David Thompson*. After Thompson’s death in 1894 Governor General Lord Aberdeen [Hamilton-Gordon*] called on Mackenzie Bowell* to form a government. Pope had a low estimate of Bowell’s talents and thought Aberdeen’s judgement deplorable. In late 1895 Tupper Sr was summoned from England to help save the Conservative party from Bowell’s follies; he became secretary of state in January 1896 and effectively took charge of the government the following month. He insisted that Pope be appointed under-secretary of state and deputy registrar general in place of Ludger-Aimé Catellier. Traditionally the office had been filled by a French Canadian; Tupper carried his point by taking steps to have a French Canadian succeed an “Englishman” as deputy head of another department. Pope was appointed on 25 April.

After Laurier’s electoral victory in June, his position was vulnerable to party pressure. He came to the swearing in of the new government – he was in charge of the Great Seal – and Laurier introduced him to his minister of justice, Sir Oliver Mowat*, as the man who had written Macdonald’s biography. At this Mowat said with a smile, “I wish he would write mine.” Still, Pope’s position was being shot at. The Toronto Globe urged a wholesale cleaning out of what it called “Tory Deputy Ministers.” On the evening of the day this exhortation appeared, the Popes were dining at the Lauriers’. On entering the drawing room, Minette curtsied before Laurier, exclaiming, “Ave Caesar Imperator, morituri te salutant.” Laurier replied, “Why morituri [those who are about to die]?” “Ah,” he continued after a moment’s reflection, “the Globe’s rubbish.” That is what it remained.

Pope used his position as under-secretary of state to effect some needed changes in the way Canada handled state business. In January 1897 he represented to Laurier the insecure, indeed parlous, way in which Canada’s public records were kept. As if to underline his argument, in February a fire in the west block threatened the archival holdings there. The government then appointed a commission of three deputy ministers, including Pope, to examine the state of the public records. Pope’s diplomatic skills were well tested – his two colleagues (John Mortimer Courtney* and John Lorn McDougall*) were not speaking to each other – but under his guidance a report emerged in November that all three could agree on. It recommended joining the records branch of the Department of the Secretary of State and the archives branch of the Department of Agriculture, something long sought by Douglas Brymner*, the ageing dominion archivist. Pope’s triumph was complete when in 1904 Arthur George Doughty* was appointed to the combined position of dominion archivist and keeper of the records.

In 1899 Laurier had asked Pope to prepare a history of the Alaska boundary question. Named an assistant secretary to the international tribunal formed in 1903, he became the Canadian government’s most important expert within the civil service during this long and arduous arbitration. In the course of his work he continually came up against the difficulty of finding current state papers. He found it extremely embarrassing to have to ask the British for copies of papers that were supposed to be in Ottawa, though no one knew where. Pope told Laurier about this problem in 1904, but nothing was done. The question had become more acute by 1908, in which year there were something like 1,600 dispatches from Britain needing action. Laurier would read excerpts in cabinet in order to decide which ministry they would go to. No record of their destinations existed except in Laurier’s head.

After the election of 1908, therefore, Pope, Governor General Lord Grey*, and James Bryce, the British ambassador to Washington, combined their efforts to get legislation ready for parliament in 1909 to establish the Department of External Affairs. On 2 June 1909 Pope left the state department to become under-secretary of state for external affairs. His role in this office was, like so much else he did, effective and unobtrusive. He did not want a large staff, but did insist, as a condition of his appointment, that William Henry Walker be brought in from the governor general’s office to become his assistant. Walker’s grasp of external business, correspondence, and treaties was exceptional, and needed. The primacy claimed by their touchy new minister, Charles Murphy*, which Pope privately resented, was largely nullified by Pope’s continued direct access to Laurier. This access could not prevent the new department from being shifted in 1909 out of the east block to the Trafalgar Building five blocks distant, at the corner of Queen and Bank. The move annoyed Lord Grey and dismayed Pope, who found the barber shop and other commercial premises on the ground floor of Canada’s Department of External Affairs a distinct lèse-majesté.

In 1911 Pope established a close working relationship with the new Conservative prime minister, Robert Laird Borden*, who, like Laurier, retained real control of external relations. As deputy head Pope handled, in addition to departmental administration, American affairs, trade and tariffs, the consular corps, and such matters of protocol as official visits. On the urging of Grey he was made a kcmg in 1912, the result of his distinguished diplomatic work in Washington on the sealing treaty of 1911 between Canada, Britain, the United States, Japan, and Russia. At this time Pope was perhaps the only high official in Ottawa to whom delicate diplomatic missions could be safely entrusted. In early 1914 Borden gave him the important task of chairing a conference of deputy heads charged with preparing a war book for Canada – a plan for handling the anticipated hostilities in Europe. For Pope, World War I would have great personal significance: four of his sons went to the front as did his sister Cecily Jane Georgina Fane*, a veteran military nurse.

The important changes in Canada’s relations with Britain that gradually came on with Borden and the war, Pope found difficult to accept. Over the course of the conflict, on foreign policy and the maturation of Canada’s position in imperial affairs, Borden relied more and more on the advice of Loring Cheney Christie*, who had joined the department in 1913. According to its official history, Pope, despite his skill, had become fixed in his handling of external affairs, “not always attentive to new challenges.”

Thoroughly loyal, Pope was not given to Canadian nationalism. Indeed, he had always been British in sentiment and thought. His compass, his son Maurice Arthur* would later observe, had been set in earlier times. Pope could not adjust it to the polarities of the 1920s. He sided with William Lyon Mackenzie King*’s non-committal response to Britain’s astounding call for military support during the Çanak crisis of 1922, but the idea of diplomatic autonomy within a British commonwealth of nations baffled him. In a letter written to his son Maurice in 1925 he asked, “How are we going to get on when every member [of the empire] claims an equal status with the rest; where each Dominion shall have . . . not only an army and navy, but also a diplomacy of its own? To my way of thinking such an Empire is an impossibility. I must leave the solution of the problem to younger and more vigorous minds than mine.”

By October 1921 Pope’s remarkable good health had broken down. A bout of rheumatic fever in the 1870s had left him with a weakened heart, and now the condition started to show itself. A leave of absence in 1921, his first in 43 years of continual public service, failed to restore him and from then on he declined. On 1 April 1925 the consummate bureaucrat retired. He had few hobbies; he used his time to draft his memoirs, which he completed only to 1907. He died on 2 Dec. 1926 and was buried in Notre-Dame Cemetery in Ottawa.

Pope was the quintessential civil servant – capable, careful, perceptive – but by the 1920s he was felt to be old-fashioned and stiff. Indeed, he had become Ottawa’s arbiter of diplomatic niceties and social forms. As the Ottawa Citizen observed, under his tutelage correspondence was “carried on with the most exacting propriety.” Sir John A. Macdonald’s insistence that “forms are things” is a good epitaph for Pope: enshrined in it are the manners and civilization of Macdonald’s time that Pope so well exemplified.

[Sir Joseph Pope was a good biographer. He was discreet in Memoirs of the Right Honourable Sir John Alexander Macdonald, g.c.b., first prime minister of the Dominion of Canada (2v., Ottawa, [1894]; repr. in 1v., Toronto, 1930) because many of the men who had worked with Macdonald, or fought against him, were still alive. His later biography, The day of Sir John Macdonald: a chronicle of the first prime minister of the dominion (Toronto, 1915), was more frank, if much shorter. Pope’s other writings include Jacques Cartier, his life and voyages (Ottawa, [1890]); Traditions (Ottawa, [1891]); and Sir John A. Macdonald vindicated: a review of the Right Honourable Sir Richard Cartwright’s “Reminiscences” (Toronto, 1912). As Macdonald’s literary executor, he published a useful selection of letters, Correspondence of Sir John Macdonald . . . (Toronto, 1921). Pope’s own papers, including the correspondence of the Macdonald estate, 1891–1922, are at LAC, MG 30, E86.

Pope’s life story, edited and completed by his son Maurice Arthur Pope, was published as Public servant: the memoirs of Sir Joseph Pope (Toronto, 1960). A well-turned piece of work and a basic foundation for this article, it is composed of two parts: Pope’s own memoirs (1857–1907) and his son’s biography of the rest of his life (1907–26). The first part was heavily edited, adding nothing and unfortunately eliminating what Maurice A. Pope called matter “merely of private interest.” Shorter biographical accounts are found in Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1898 and 1912) and Standard dict. of Canadian biog. (Roberts and Tunnell). A family tree and history are provided in the introduction to Maurice A. Pope’s Letters from the front, 1914–1919, ed. Joseph Pope (Toronto, 1993). Louise Reynolds, Agnes: the biography of Lady Macdonald (Toronto and Sarasota, Fla, 1979), has much about Pope in its later chapters. For the development of the Department of External Affairs during his time, see John Hilliker and Donald Barry, Canada’s Department of External Affairs (2v., Montreal and Kingston, Ont., 1990–95). [p.b.w.]

Revisions based on:

Ancestry.com, “Ontario, Canada, deaths and deaths overseas, 1869–1947”: www.ancestry.ca (consulted 16 Oct. 2018).

Cite This Article

P. B. Waite, “POPE, Sir JOSEPH,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 21, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/pope_joseph_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/pope_joseph_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | P. B. Waite |

| Title of Article: | POPE, Sir JOSEPH |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2005 |

| Year of revision: | 2020 |

| Access Date: | February 21, 2026 |