Source: Link

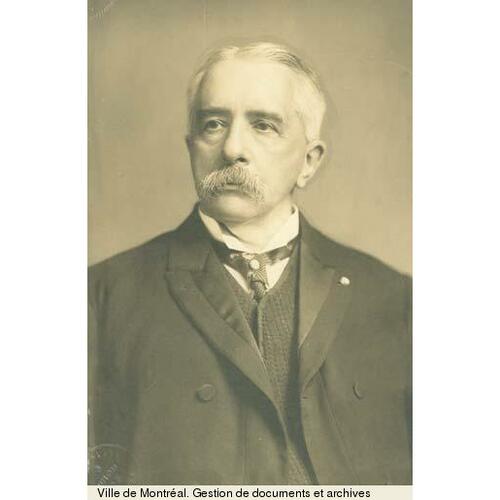

BOUCHER DE LA BRUÈRE, PIERRE (baptized Joseph-René-Pierre-Hypolite), lawyer, journalist, author, office holder, and politician; b. 5 July 1837 in Saint-Hyacinthe, Lower Canada, son of Pierre-Claude Boucher* de La Bruère, a physician, and Hippolyte Boucher de Labroquerie; m. there 8 Jan. 1861 Victorine Leclère, and they had five daughters and four sons who survived him; d. 6 March 1917 at Quebec and was buried 10 March in Saint-Hyacinthe.

Pierre Boucher de La Bruère belonged to the distinguished Boucher de Boucherville family. He was a descendant of Pierre Boucher*, the founder and seigneur of Boucherville, and the grandson of René Boucher de La Bruère, the seigneur of Montarville. As he was an only son, it is not surprising that he was sent to do classical studies, which he began in 1846 at the Séminaire de Saint-Hyacinthe. In 1857–58 he studied law at the Université Laval and he was called to the bar of Lower Canada on 5 March 1860. His marriage the following year to the daughter of a Saint-Hyacinthe notary astonished the town’s social élite, since it seemed that the young couple came from families of opposing political views. The bridegroom’s father had been one of a small group of Saint-Hyacinthe’s most prominent Patriotes in 1837–38, while the bride’s father, Pierre-Édouard Leclère*, who was superintendent of police in Montreal at the time, had been one of their bitterest adversaries. Leclère had been responsible for the arrest and imprisonment of Dr Boucher de La Bruère in 1838. Since then, he had settled in Saint-Hyacinthe with his family. But after 1840 Pierre’s father had in fact gradually realigned himself with those who accepted the new order of things. In 1858, perhaps for political reasons or for neighbourliness, he wrote Leclère a rather strange letter stating that he remembered him as the man who had brought him the news of his release from prison in 1838. As for Pierre, his initial political orientation is indisputable, given the handwritten text of the address he gave as a law student in 1859 to the Cercle d’Union de Saint-Hyacinthe, an association of young people formed to counteract the influence of the local Institut Canadien. In this speech he recalled the history of the Séminaire de Saint-Hyacinthe, emphasizing the clergy’s claims to fame and its role in maintaining the national character. Thus, despite appearances, the marriage of Pierre Boucher de La Bruère and Victorine Leclère did not pose the problems faced by families in conflict.

Three months after his wedding, Boucher de La Bruère, as the new editor of Le Courrier de Saint-Hyacinthe (with Moïse Demers as its new owner), wrote an open letter to the clergy. Dated 23 April 1861, it set out a new direction for the publication, one guaranteed to “dispel the legitimate mistrust of a newspaper that had deserved the censure of the religious superiors.” From 1861 to 1866, the paper’s contents would generally be written by an editorial committee whose members, all youthful friends and all opposed to the local Rouges, included Honoré Mercier*, Paul de Cazes, and Michel-Esdras Bernier, as well as Boucher de La Bruère himself. Oscar Dunn* took over on 5 June 1866. Thereafter the paper gave unqualified support to the Conservative party of George-Étienne Cartier*, its plan for confederation, and its alliance with the clergy. During this period Boucher de La Bruère had published a pamphlet entitled Le Canada sous la domination anglaise: analyse historique (Saint-Hyacinthe, 1863), and he is credited with having written Réponses aux censeurs de la Confédération (1867), a tract which also appeared in Le Courrier.

Boucher de La Bruère had been practising law in Saint-Hyacinthe since 1860 and from 1870 to 1875 he also served as protonotary for the judicial district of Saint-Hyacinthe. Having resumed the editorship of Le Courrier in 1875, he held it for the next 20 years, and he took over as owner on 17 Sept. 1877, shortly before he was appointed to the Legislative Council for the division of Rougemont. In 1878 he became a partner in the legal firm of Tellier, de La Bruère et Beauchemin in Saint-Hyacinthe.

The man whom the Conservative government of Charles Boucher de Boucherville had elevated to the rank of legislative councillor was not just a lawyer, journalist, and good Conservative. He was also known as a promoter of sugar-beet farming and processing, and as the founder of the “École des Arts et Dessins Industriels” at Saint-Hyacinthe in 1874, an institution affiliated with the Council of Arts and Manufactures of the Province of Quebec. He encouraged the butter and cheese industry and played a leading part, through meetings held at Saint-Hyacinthe, in creating the Industrial Dairy Society of the Province of Quebec; the society was incorporated on 1 May 1882, and he served as its president from 1882 to 1889. Boucher de La Bruère had a significant though less important role in founding the dairy school at Saint-Hyacinthe in 1892. His attachment to his region is shown, as well, by the publication of Saint-Hyacinthe illustré (1886). His interest in education is expressed in De l’éducation: conférence faite en février 1881 devant le Cercle catholique de Québec (1881), while his more philosophical ideas are set out in L’existence de l’homme . . . (1884).

On 4 March 1882 Boucher de La Bruère, now in his mid forties, was appointed speaker of the Legislative Council and, as such, he was a member of Joseph-Adolphe Chapleau*’s ministry. A few months later, however, an amendment to the British North America Act put an end to the practice by which the speaker was automatically on the Executive Council. He retained the speakership under the Conservative governments of Joseph-Alfred Mousseau*, John Jones Ross*, and Louis-Olivier Taillon*, but was dismissed on 23 April 1889 by Mercier’s Nationalist-Liberal government, and was replaced by Henry Starnes*, a Liberal. Irritated, he wrote Les principes de l’Hon. M. Mercier (Saint-Hyacinthe, 1890). When the Conservatives were returned to power in 1892 he resumed the speakership, and he retained it until April 1895. The Taillon government then transferred him to the theoretically non-political superintendency of public instruction as Gédéon Ouimet*’s successor; Ouimet became legislative councillor for Rougemont in his place.

Now nearly 60 years old, Boucher de La Bruère moved to Quebec. He would remain superintendent until 10 May 1916, and thus from 1897 to 1916 the province would have a Conservative in this position, even though its governments – under Félix-Gabriel Marchand*, Simon-Napoléon Parent, and Sir Lomer Gouin* – were Liberal. Boucher de La Bruère was not a leading protagonist in the debate engendered in 1897 and 1898 by a controversial bill that the Marchand government drew up and Provincial Secretary Joseph-Emery Robidoux introduced. The measure was intended to give authority over the school system to a minister of education, the arrangement that had existed from 1867 to 1875. Supporters of responsibility to the people faced off against defenders of “complete separation between politics and public education,” as Boucher de La Bruère would later write in Le Conseil de l’instruction publique et le comité catholique (Montréal, 1918). This lengthy posthumous work is both the history of an institution and a defence, strongly tinged with social and ideological conservatism, of the superintendent’s views and accomplishments. However, the author discreetly did not make himself the star or give himself all the credit.

For some 20 years Boucher de La Bruère chaired both the Council of Public Instruction, a general body that was attached to the provincial secretary’s office and was quite restricted in its activities, and the council’s Catholic committee, a more active group. He was in charge of routine affairs for the council. It is rather difficult, in the absence of any detailed study, to ascertain the extent to which he was responsible for the progress – and the apathy – in the provincial educational system of his day. He seems to have been particularly interested in the role of school-board members and in technical education, domestic science, and the creation of normal schools for girls. He considered it important for senior officials to keep themselves well informed, through reading and personal visits, about the systems of education and the current practices in Europe and the United States. His pamphlet Education et constitution (Montréal, 1904) calls for the observance of provincial rights in the field of education.

Boucher de La Bruère did not resign his post until 1916, when illness left him no choice, and he died shortly afterwards, on 6 March 1917, in his 80th year. According to contemporary witnesses, he always commanded respect. He was apparently recognized as a man of culture, with “a dignified life and appearance,” in the words of Robert Rumilly*, and, despite his Conservative allegiance, a marked independence of mind. In the will he dated 5 July 1916, Boucher de La Bruère did not leave his family papers to his eldest son, Pierre-Édouard, who was a farmer in Coaticook. They went to Montarville*, who in 1914, after a career as a journalist that included a stint as news editor at Le Devoir, had become the director of the Public Archives of Canada in Montreal.

ANQ-M, CE2-5, 7 juill. 1837, 8 janv. 1861. Arch. du Séminaire de Saint-Hyacinthe, Qué., AFG3 (fonds J.-S. Raymond); 4 (fonds P.-É. Leclère); 7 (fonds J.-A. Chicoyne); 8 (fonds Pierre Boucher de La Bruère); 41 (fonds P.-A. Saint-Pierre); ASE3 (Relations avec les autorités civiles); 6 (Administration générale); 13 (Administration financière); 14 (Assoc. des élèves); 18 (Imprimés); BSE10 (Assoc.); 11 (Journaux); 19 (Arch. administratives de la Soc. d’hist. régionale de Saint-Hyacinthe). Arch. du Séminaire de Trois-Rivières, Qué., 0032 (coll. Montarville Boucher de La Bruère). Le Canadien, 22 mai 1871. Le Courrier de Saint-Hyacinthe, 1er mars 1866, 10 juill. 1974. Le Devoir, 8 mars 1917. La Minerve, 25 juin 1832. Le Pionnier de Sherbrooke (Sherbrooke, Qué.), 9 mars 1882. L.-P. Audet, Histoire du Conseil de l’instruction publique de la province de Québec, 1856–1964 (Montréal, 1964). Jean de Bonville, La presse québécoise de 1884 à 1914; genèse d’un média de masse (Québec, 1988). Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1898 and 1912). Ivanhoë Caron, “Inventaire des documents relatifs aux événements de 1837 et 1838, conservés aux Archives de la province de Québec,” ANQ, Rapport (Québec), 1925–26: 217–18. C.-P. Choquette, Histoire de la ville de Saint-Hyacinthe (Saint-Hyacinthe, 1930). J.-N. Dion et al., Saint-Hyacinthe; des vies, des siècles, une histoire; notices biographiques (texte polycopié, Saint-Hyacinthe, 1984; copy available in the Arch. du Séminaire de Saint-Hyacinthe). Jean Hamelin et al., La presse québécoise. Industrial Dairy Soc. and Dairy School of the Prov. of Quebec, Rapport (Québec), 1902. Industrial Dairy Soc. of the Prov. of Quebec, Rapport (Québec), 1884. [Charlotte Leclerc Bonenfant], Saint-Hyacinthe-de-Montarville; fragments d’histoire (Saint-Bruno-de-Montarville, Qué., [1992]). RPQ. Rumilly, Hist. de la prov. de Québec, vol.6. Wallace, Macmillan dict.

Cite This Article

Jean-Paul Bernard, “BOUCHER DE LA BRUÈRE, PIERRE (baptized Joseph-René-Pierre-Hypolite),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 1, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/boucher_de_la_bruere_pierre_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/boucher_de_la_bruere_pierre_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | Jean-Paul Bernard |

| Title of Article: | BOUCHER DE LA BRUÈRE, PIERRE (baptized Joseph-René-Pierre-Hypolite) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1998 |

| Year of revision: | 1998 |

| Access Date: | March 1, 2026 |