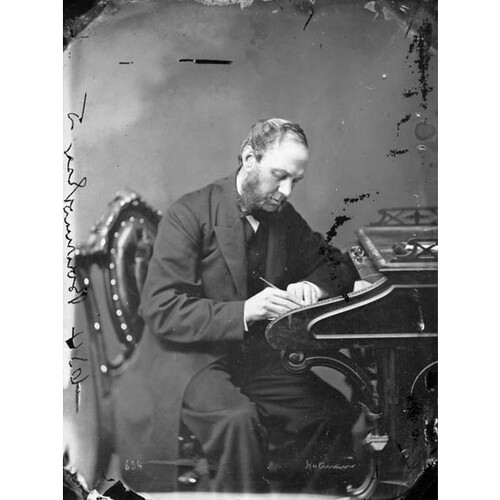

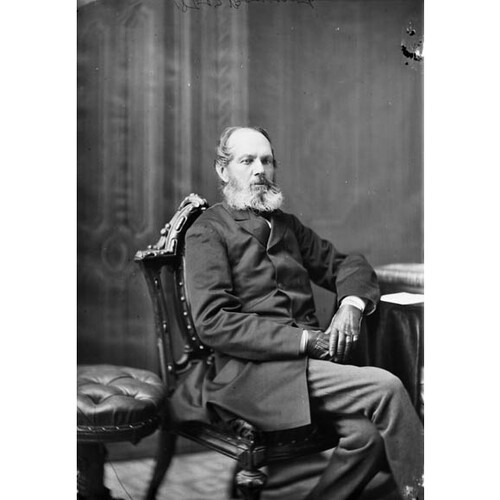

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

BOURINOT, JOHN, merchant and politician; baptized 31 March 1811 in Grouville, Jersey, son of Jean Bourinot and Elizabeth Blampied; m. 19 Sept. 1835 Margaret Jane Marshall in Arichat, N.S., and they had six sons and five daughters, of whom one son and three daughters died in infancy or early childhood; d. 21 Jan. 1884 in Ottawa and was buried in Sydney, N.S.

The Bourinots were Huguenots from Normandy who fled to Jersey following the revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685, placing them among the thousands of French political and religious refugees who escaped to the Channel Islands over the years. At some point the family became involved in the Atlantic fishery, the mainstay of the Jersey economy, and “for centuries held a position of influence” on the island.

After being educated in nearby Caen, France, John Bourinot was sent to Nova Scotia in about 1830 to work in Arichat, on the south shore of Cape Breton Island, at the Robin family’s fishing post, which had been in operation since about 1770 [see Charles Robin*]. He soon moved to Sydney, the island’s political centre, and established a wholesale and retail mercantile business. In 1835 Bourinot married Jane Marshall, a daughter of John George Marshall* and Catherine Jones. It was a wise marriage for an ambitious young man: Marshall was chief justice of the Court of Common Pleas for Cape Breton. By 1838 Bourinot had been made a justice of the peace, and in the 1840s he was appointed surveyor of shipping at Sydney.

Bourinot’s fluency in both French and English (which he spoke with a distinct French accent) made him something of a rarity in Cape Breton and proved beneficial to his career. In 1850 the government of France appointed him its consular agent in Sydney on the recommendation of Thomas Ducos, commander of the French naval station at Saint-Pierre. Four years later Bourinot was promoted to honorary vice consul; for 30 years he would be the main representative of France in Atlantic Canada. His work in this role had a significant impact on Sydney, then a small and struggling village, because the frequent visits of French ships greatly benefited local merchants and farmers. By the 1850s he was a leading citizen, and in the early 1860s Richard John Uniacke (a grandson of politician Richard John Uniacke*) recorded that Bourinot’s harbourfront home – where a tricolour was hoisted whenever a French vessel arrived – was one of Sydney’s “most conspicuous private dwellings.” In 1863 Bourinot became a Lloyd’s of London maritime-insurance agent, and at some point he served as lieutenant-colonel of the 1st Regiment of Cape Breton militia.

Bourinot energetically promoted the economic development of Cape Breton, which the provincial government had largely neglected following its annexation in 1820. He was one of the earliest business leaders to recognize the importance of the island’s vast coalfields to industry, steamships, and railways. In 1851 he joined local businessmen in promoting – albeit unsuccessfully – Sydney as the ice-free port required by the European and North American Railway [see John Alfred Poor*]. The Reciprocity Treaty of 1854, together with the termination of the General Mining Association’s monopoly on Cape Breton’s coalfields four years later, stimulated extraordinary growth in the coal industry. Bourinot likely helped his son Marshall secure the rights to what became known as the Block House mine, one of the largest producers in the area.

Although Bourinot was elected to the legislature in 1859 as a Conservative, his loyalty was to Cape Breton first, not the party. When re-elected by acclamation in 1863, he vowed that he would “never support any government which shall refuse to do that justice … which the county of Cape Breton is entitled to when we consider either her population or wealth of resources.” This stance determined his attitude towards confederation. He had supported Joseph Howe*’s call in 1861 for a union with the other Maritime colonies and even with Canada because, as he put it three years later, “I felt it was better to be an appendage to Canada than to Nova Scotia, as we might then obtain more justice than we had received in the past from Nova Scotia.”

Nevertheless, in 1865, when Premier Charles Tupper* introduced the terms of confederation agreed to at the Quebec conference the previous year, Bourinot was opposed. He thought confederation would not benefit Nova Scotia economically because the Reciprocity Treaty of 1854 had made the United States the largest market for its two major exports, fish and coal. He was equally concerned that the province would have too little representation in parliament to have much influence. His opinion was based on his bitter experience in the Nova Scotia legislature, where “no member from Cape Breton could for years raise his voice on behalf of that island without being met with sneers, if indeed he was heard at all.”

The situation changed when the United States terminated the reciprocity treaty in March 1866 and the Fenians attempted to attack New Brunswick in April. Cape Breton suddenly needed a new market for its coal, and Nova Scotia required military support that Great Britain was reluctant to provide. Confederation now seemed more attractive, especially since the Quebec resolutions promised federal funding to build the Intercolonial Railway [see Walter M. Buck]. When William Miller, the young mla for Richmond County, proposed approving confederation on the condition that its terms be modified at a subsequent conference in London, Bourinot and four of the other seven Cape Breton mlas endorsed the idea, as did a comfortable overall majority in the legislature.

Bourinot claimed in 1867 that he had reached his decision after “reading attentively that the opinions of the most intelligent men in England were favourable to Confederation.” He also knew the project was popular in Cape Breton, and he was influenced by his eldest son, John George Bourinot*, whose Halifax newspaper, the Evening Reporter, strongly advocated union with Canada. More fundamentally, John Bourinot’s support for confederation in 1866 had reflected his core belief that Cape Breton was destined to become the industrial centre of the new dominion because it possessed most of its coal as well as excellent harbours at Sydney and Louisbourg. Instead of being “an insignificant appendage of Nova Scotia,” Cape Breton would become “an important integral part of the nationality.”

The fact that Bourinot was appointed one of Nova Scotia’s first senators understandably led some to conclude that he had sold his vote, but there is no evidence to support this claim. (In fact, he was not one of Tupper’s original choices for the seat and was offered it only after his vote had already been cast.) Bourinot welcomed the appointment because he believed it would enable him to press Cape Breton’s interests at the centre of power. For eight years he promoted the island’s coal industry, the enlargement of the St Peters Canal to enable ocean-going vessels to enter Bras d’Or Lake, and – somewhat quixotically – Louisbourg’s potential to replace Halifax as Canada’s major Atlantic port. He accomplished very little and eventually became disillusioned. In February 1875 he told the Senate that he was “sadly disappointed … that justice had not been done,” that “no public works of importance … had yet been undertaken,” and that Cape Breton “had received only a small share of the consideration to which the Government had pledged itself before Confederation.” Afterwards he limited his Senate activities to minor committee work.

Bourinot appears to have had more success in advancing his son’s career. In 1869 he had likely helped secure the Senate’s English clerkship for John George, whose skill in shorthand and support for confederation made him well qualified. Thirteen years later Senator Bourinot’s influence was probably a factor in his son’s appointment as clerk of the House of Commons. John George would go on to become an international authority on parliamentary procedure and constitutional law, a popular and respected historian, and the first honorary secretary of the Royal Society of Canada.

On 18 Jan. 1884, while in Ottawa, John Bourinot was stricken with paralysis. He died three days later. Senator Robert Barry Dickey, a long-time colleague, rightly recognized that “justice to Cape Breton seems to have been the key-note of his parliamentary life,” but the best that Sir Alexander Campbell*, the Conservative leader in the Senate, could say of him was that he had been “a useful member.”

Cape Breton Univ., Beaton Instit. (Sydney, N.S.), MG 12.16 (Bourinot family fonds). Library and Arch. Can. (Ottawa), R12555-1-6 (Sir Charles Tupper fonds, political papers). N.S. Arch. (Halifax), MG 1, vols.145–49 (J. G. Bourinot fonds), family scrapbooks. Halifax Evening Reporter, 9 May 1863. M. A. Banks, Sir John George Bourinot, Victorian Canadian: his life, times, and legacy (Montreal and Kingston, Ont., 2001). J. G. Bourinot, Confederation of the provinces of British North America (Halifax, 1866). R. H. Campbell, “Confederation in Nova Scotia to 1870” (ma thesis, Dalhousie Univ., Halifax, 1939). Can., Senate, Debates, 1875: 24, 50, 220; 1884: 33. Margaret Conrad, At the ocean’s edge: a history of Nova Scotia to confederation (Toronto and Buffalo, N.Y., 2020). Donald Nerbas, “Empire, colonial enterprise, and speculation: Cape Breton’s coal boom of the 1860s,” Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth Hist. (London), 46 (2018): 1067–95. N.S., House of Assembly, Debates and proc., 1864: 110; 1866: 305; 1867: 3–4. Robert Pichette, “Jean Bourinot et la présence de la France au Canada atlantique au XIXe siècle,” in Essays in French colonial history: proceedings of the 21st annual meeting of the French Colonial Historical Society (East Lansing, Mich., 1997), 195–212. Standard dict. of Canadian biog. (Roberts and Tunnell), vol.1. B. D. Tennyson, “Economic nationalism, confederation and Nova Scotia,” in The causes of Canadian confederation, ed. Ged Martin (Fredericton, 1990); “Economic nationalism and confederation: a case study in Cape Breton,” Acadiensis, 2 (1972–73), no.1: 39–53; “John George Bourinot, m.h.a. and senator,” in Essays in Cape Breton history, ed. B. D. Tennyson (Windsor, N.S., 1973), 35–48. [R. J. Uniacke] et al., Uniacke’s “Sketches of Cape Breton” and other papers relating to Cape Breton Island, ed. and intro. C. B. Fergusson (Halifax, 1958).

Cite This Article

Brian Douglas Tennyson, “BOURINOT, JOHN,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 26, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/bourinot_john_11E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/bourinot_john_11E.html |

| Author of Article: | Brian Douglas Tennyson |

| Title of Article: | BOURINOT, JOHN |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1982 |

| Year of revision: | 2025 |

| Access Date: | February 26, 2026 |