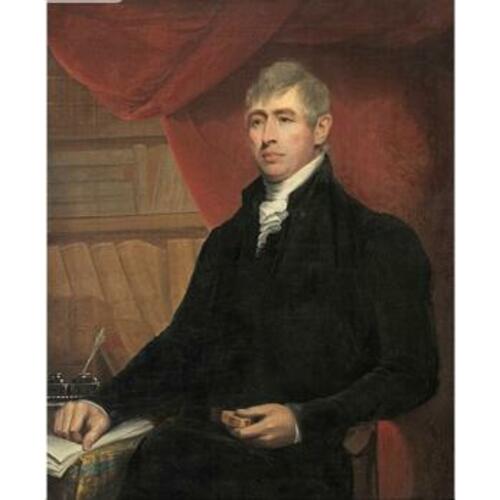

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

UNIACKE, RICHARD JOHN, lawyer, office holder, and politician; b. 22 Nov. 1753 in Castletownroche (Republic of Ireland), fourth son of Norman Uniacke and Alicia Purdon; m. first 3 May 1775 Martha Maria Delesdernier in Hopewell Township (N.B.), and they had six sons, including Norman Fitzgerald*, Richard John, Robert Fitzgerald*, and James Boyle*, and six daughters; m. secondly 14 Jan. 1808 Eliza Newton in Halifax, and they had one son; d. 11 Oct. 1830 in Mount Uniacke, N.S.

As Roman Catholics, the Uniackes had suffered much repression during the periods of Tudor and Cromwellian rule in Ireland, but by the early 1700s they had become staunch Protestants and adherents to the British crown with powerful patrons. After going to school at Lismore, Richard John was articled to a Dublin attorney, since his father had become alarmed by his son’s increasing preference for the teachings of the local Catholic priest. In Dublin Uniacke seems to have taken part in political agitation probably related to the cause of Catholic relief, and so crossed his father that the young man “in passion” left home “to seek his fortune in the New World.” First going to the West Indies, he arrived in Philadelphia in the summer of 1774 and formed a partnership with Moses Delesdernier*, a trader from Nova Scotia. After a dangerous voyage they arrived at Hopewell Township on the Petitcodiac River (N.B.), where Delesdernier became agent for the proprietors. In May 1775 Uniacke married Delesdernier’s 12-year-old daughter, Martha Maria. He was to remain devoted to her until her death in 1803.

The extent of Uniacke’s involvement on the rebel side of the uprising led by Jonathan Eddy* on the Chignecto Isthmus during the autumn of 1776 is difficult to determine. He was certainly initially sympathetic but seems to have supported the rebels out of fear of reprisals. Late in the year he was arrested and sent to Halifax to be tried for treason but was released, probably through the influence of Irish officers in the garrison and local officials who knew his family. In 1777 he embarked for Ireland to finish his legal studies. On 22 June 1779 he was admitted as attorney of King’s Inns, Dublin, and after his return to Nova Scotia he was admitted to the bar on 3 April 1781. His Irish connections had secured him an interview in 1780 with Lord George Germain, secretary of state for the American colonies, who promised him the attorney generalship of Nova Scotia upon the first vacancy. One occurred in late 1781, but the position went to the more senior Richard Gibbons*, and Uniacke was appointed solicitor general on 27 Dec. 1781. He was elected to the House of Assembly in 1783 for Sackville Township.

Uniacke’s prospects looked excellent, but the arrival of the loyalists forced him to fight for his professional survival. The attorney generalship became vacant in 1784, but he was again passed over, this time in favour of the loyalist Sampson Salter Blowers*. However, thanks to his friend and patron, Governor John Parr*, he was made advocate general of the Vice-Admiralty Court the same year. In the assembly Uniacke became the leader of the pre-loyalists in their struggle with the loyalists to obtain patronage, and he became speaker in 1789. Parr died two years later, and a loyalist, John Wentworth*, became lieutenant governor. Wentworth’s appointment, the antipathy of the chief justice, Thomas Andrew Lumisden Strange*, and the enmity of prominent loyalists such as Blowers and Thomas Henry Barclay combined to exclude Uniacke from government and influence, and he declined to run in the 1793 elections. During the 1790s Uniacke clashed with Wentworth on several issues, once in connection with arrangements to defend Halifax against a threatened French attack. Wentworth responded by using his private correspondence with British officials to describe Uniacke’s conduct as “dark and insidious secretly connected with seditious purposes.”

When Strange resigned in 1797 it was accepted that Attorney General Blowers would succeed him. The loyalists were determined that Uniacke should never become attorney general, and Wentworth recommended that Jonathan Sterns, another loyalist and Blowers’s protégé, receive the position. Uniacke appealed to the home secretary, the Duke of Portland, claiming that he should succeed by seniority and citing his family’s patrons, one of whom was Portland’s brother-in-law. Portland appointed Uniacke attorney general on 9 September (the date on which Blowers became chief justice) and administered to Wentworth one of the sharpest rebukes to a Nova Scotian governor on record. The bitterness between Uniacke and Sterns was deep, and after Uniacke had severely beaten Sterns in a street fight Blowers challenged Uniacke to a duel. Blowers and Uniacke were bound over to keep the peace but the enmity between them was to last until Uniacke’s death.

Now more secure in his position, Uniacke re-entered the assembly in 1798 for Queens County and the next year became speaker, a position he held until he retired in 1805. In that year he published a compilation of Nova Scotian statutes between 1758 and 1804, commonly known as Uniacke’s laws and the standard reference work until 1851. While speaker he resisted Wentworth’s attempts to challenge the assembly’s right to supervise the provincial finances, and he worked to bring about Wentworth’s downfall by castigating the lieutenant governor and his appointments in communications with Lord Castlereagh, the colonial secretary. Although Wentworth had recommended him, Uniacke refused to become a member of Wentworth’s Council, and he was not appointed until 1808, after Wentworth had been replaced by Sir George Prevost*. For two decades after that date he was to occupy an extremely influential position in the government of Nova Scotia.

Uniacke’s constitutional thinking had been moulded by his study of Sir William Blackstone’s Commentaries on the laws of England, and it was rooted firmly in the 18th century. He wanted provincial governments to follow the model envisaged by the 18th-century British constitution, in which the fundamental principle was the balance of powers between the crown, lords, and commons and in which, he believed, the executive and legislature each had their own clear-cut functions. Uniacke ignored the changes in his lifetime which led to the executive becoming responsible to parliament; according to him, all public officials answered only to the king. His attitude was also much influenced by the excesses of the French revolutionaries, who he believed had attempted to “destroy the principles of true religion and . . . subvert the rules of civil government.” In the 1820s he expressed fears that the revolutionary “heresies” of atheism and democracy spreading to the “hoards of semi-barbarians” in the south and west of the United States would engulf New England and then British North America.

To avert such a catastrophe, Uniacke advocated unions of the Maritime colonies and of the Canadas, beginning in 1806 when he presented a memoir on British North America at the Colonial Office. By 1821, however, he had concluded that only a general union would save the colonies from republicanism, atheism, and democracy, and in 1822 the introduction in the British parliament of a bill to bring about the union of the Canadas spurred him to propose a general union to Frederick John Robinson, president of the Privy Council committee for trade. Others in British North America such as Jonathan Sewell*, John Beverley Robinson*, and John Strachan* were also interested in a general union, although not always for the same reasons, and several such proposals arrived in London about this time. In 1826 Uniacke brought his “Observations on the British colonies in North America with a proposal for the confederation of the whole under one government” to the Colonial Office. The “Observations” read in parts like the British North America Act of 40 years later, and were at once the most persuasive of the various schemes and the last attempt to bring about new intercolonial arrangements until the 1839 report of Lord Durham [Lambton*]. By 1826 proposals for any sort of union were not regarded with much favour in Britain, and the “Observations” were never printed, although Uniacke’s son James Boyle gave a copy to Durham.

Uniacke understood with greater prescience than any other British North American of his day that the British government would have to accept a substantial increase in colonial self-government if it allowed the colonies the commercial freedom he considered essential. For more than 30 years he struggled for what he called “the grand principle of free trade,” by which he meant the removal of those laws that prevented the colonies from trading wherever and in whatever they wished. From the early 1790s he wanted free ports opened in Nova Scotia so that the province could become an entrepôt for British, West Indian, and American goods. His relationship with the Halifax merchants was close and on several occasions they turned to him as the Nova Scotian most capable of putting their case to the British government. The joint report of the assembly and Council which criticized the Convention of 1818 between Britain and the United States was mostly drafted by him and comes alive with his pungent and forceful language. In it he stated that Britain “must strengthen her colonies in North America . . . to enable them to stand by her side with effect, when the struggle for which the United States are manifestly preparing shall take place.”

The least edifying aspect of Uniacke’s public career was his opposition to any diminution of the role of the Church of England as the established church in Nova Scotia. As a youth he was attracted to the Anglican ministry, but rebelled against the “insatiable rapacity” of its servants. In the 1780s and 1790s he was a member of Mather’s (St Matthew’s), the dissenting church in Halifax, and it was not until 1801, for reasons still unknown, that he began to pay pew rents at St Paul’s Anglican Church. After that date, however, he became a leading member of the extreme wing of the church and state party. Convinced that an established church was a necessity if Christian civilization was to triumph in its struggle against what he considered the revolutionary heresies of his day, he was utterly intransigent in his opinion that the Church of England was a bulwark of the British constitution. No one fought as hard as Uniacke to stop the secessionist Presbyterians led by Thomas McCulloch* from turning Pictou Academy into a college, and as principal law officer he drafted the restrictive charter of the academy in 1820. His opposition in 1819 to the otherwise almost unanimous consent of the assembly and Council to a bill granting dissenting ministers the right to marry by licence was most clearly expressed when he declared that “no good government can long exist without an established religion . . . and if such a bill should pass into law the final overthrow of the church must soon follow and with it the constitution of our fathers must perish.”

Despite these extreme opinions, Uniacke was not intolerant of other religious beliefs, and in the 1820s he was one of the foremost leaders in the struggle for Catholic emancipation in Nova Scotia. At the same time, he was sometimes conciliatory in matters which affected the established church. It was Uniacke who, during a visit to England in 1806, was able to influence the archbishop of Canterbury and the British government to require subscription to the Thirty-Nine Articles from students at King’s College only upon graduation and not on entrance. However, other members of the board of governors of the college conspired to enforce subscription upon entrance.

Uniacke made a substantial fortune, amassed mainly from his fees as advocate general of the Vice-Admiralty Court during the Napoleonic Wars and the War of 1812. This wealth he spent on the education of his 12 surviving children, a large town house in Halifax, and his country home, Mount Uniacke. The Mount, completed by 1815, was built 25 miles northwest of Halifax on an estate of 11,000 acres. It symbolized his triumph over the vicissitudes of life in the New World and his faith in Nova Scotia as the home for his children. Later generations remembered as grand and remarkable the sight of Uniacke and his six sons, all of whom were over six feet tall, walking through the streets of Halifax.

Uniacke’s politics may best be described as those of a moderate tory in his constitutional views and an extreme tory when it came to church and state. His was not, however, a conservatism that simply defended the status quo. The fetters that bound colonial trading had to be removed, the colonial constitutions changed radically, and a great colonial union created; only with the adoption of these measures could British North America survive the onslaught he long feared.

Contemporaries remembered Uniacke mostly for the sheer force of his character and his exuberance. He loved life, and family and friendships were essential to his existence. His was a personality of exaggerations and his judgements of men and events were sometimes clouded by raw emotion. He was ambitious for himself and his children, and although his ambitions were never entirely fulfilled, he achieved more than most men. Mount Uniacke is today a historic house open to the public, where the personality of a “remarkable and extraordinary man” still lives.

PAC, MG 11, [CO 217] Nova Scotia A, 96–171; MG 23, C6. PANS, MG 1, 926–27; 1769, no.42; RG 1, 192–95, 218W–XX, 222–36, 286–91. PRO, CO 217/59–160; CO 218/7–30 (mfm. at PANS). SRO, GD45 (mfm. at PAC). N.S., House of Assembly, Journal and proc., 1781–1830. B. [C. U.] Cuthbertson, The old attorney general; a biography of Richard John Uniacke (Halifax, [1980]). “Trials for treason in 1776–7,” ed. J. T. Bulmer, N.S. Hist. Soc., Coll., 1 (1879): 110–18. R. G. Fitzgerald-Uniacke, “Some old County Cork families: the Uniackes of Youghal,” Cork Hist. & Archaeological Soc., Journal (Cork, [Republic of Ire.]), 3 (1894), nos. 30–31, 33–36. Murdoch, Hist. of N.S., vol.3. L. G. Power, “Richard John Uniacke,” N.S. Hist. Soc., Coll., 9 (1895): 73–118.

Cite This Article

B. C. Cuthbertson, “UNIACKE, RICHARD JOHN (1753-1830),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 6, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 1, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/uniacke_richard_john_1753_1830_6E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/uniacke_richard_john_1753_1830_6E.html |

| Author of Article: | B. C. Cuthbertson |

| Title of Article: | UNIACKE, RICHARD JOHN (1753-1830) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 6 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1987 |

| Year of revision: | 1987 |

| Access Date: | March 1, 2026 |