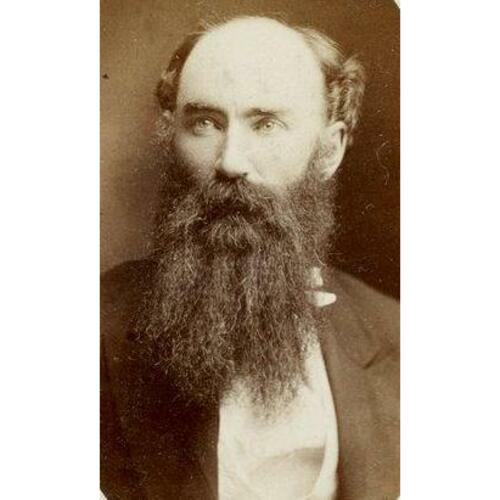

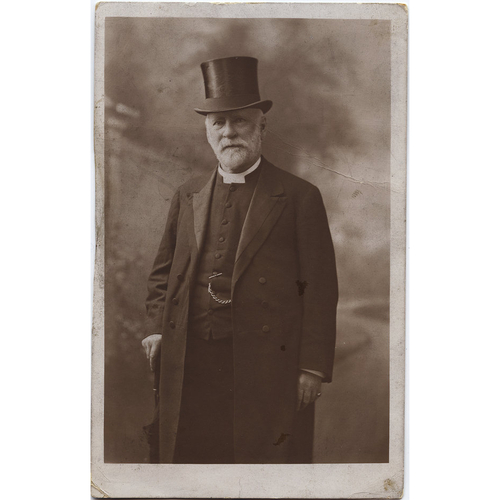

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Bryce, George, Presbyterian minister, educator, and author; b. 22 April 1844 near Mount Pleasant, Upper Canada, son of George Bryce and Catherine Henderson; brother of Peter Henderson Bryce; m. 17 Sept. 1872 Marion Samuel (d. 1920) in Toronto, and they had a son who died in infancy; d. 5 Aug. 1931 in Ottawa.

George Bryce was the eldest child of parents from Perthshire, Scotland. In 1843 they had immigrated to Brant County, Upper Canada, where his father would later serve as a justice of the peace. George was born and raised on the family farm near Mount Pleasant. After completing high school in Brantford, he entered the University of Toronto in 1863, where he took courses in both arts and science. He was captain of the football club and served with the university’s militia unit, the 2nd Battalion, Queen’s Own Rifles [see William Smith Durie*], under Alfred Booker* in the battle against the Fenians at Ridgeway in 1866. A high achiever throughout his time at university, he graduated with a ba in 1867, winning numerous prizes, including the silver medal in natural science, and completed an ma the next year. Having decided on a career in the Presbyterian ministry, in 1869 he entered Toronto’s Knox College, graduating two years later. He briefly served as an assistant minister in Chalmers Free Church in Quebec City before accepting a position in the new province of Manitoba.

In response to pleas from the settlers of Kildonan (Winnipeg) and local minister John Black*, the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in Canada established a new college in 1871 and recruited Bryce to serve as a professor and run the school. At just 27 he had the stamina required to set up Manitoba College in Kildonan while ministering to the congregation of Knox Church in Winnipeg. He also participated in organizing about 20 fledgling congregations along the homesteading frontier.

Fund-raising for the college necessitated frequent trips to Ontario, where Bryce met Marion Samuel, a Scot who had immigrated to Toronto to become headmistress of a school there. Following their marriage in 1872 she joined Bryce in Manitoba, where she would be as active as her husband. She became involved in many social causes and served on the board of the Winnipeg General Hospital, of which George was a director from 1874 to 1879. In 1878 he had received his llb from the University of Toronto, having written the examinations while on his trips back east. The institution conferred upon him an honorary lld six years later.

In the fall of 1874 Bryce had moved Manitoba College from Kildonan to Winnipeg, which he believed would be the most populous centre of the province. Under his supervision an ambitious new building was raised, but by the time the project was completed in 1882, it was over budget by one-third. The General Assembly demanded better financial management, and the following year it appointed the Reverend John Mark King* of Toronto as professor of theology and the institution’s first principal. He took over administration from Bryce, who had never been granted that title. Though the inflation that accompanied the property boom during the building’s construction and the subsequent depression contributed to the debt incurred, Bryce was accorded the lion’s share of the blame, ending his own hopes for the principalship and clouding his future relations with King. The falling out with King and with the Reverend James Robertson*, superintendent of the Presbyterian Church’s national home-missions committee, hampered Bryce’s career, though he continued to be very active, particularly as the long-time chair of the Winnipeg home-missions committee. But increasingly he turned to the world outside the college and church for fulfillment. His personality – energetic, optimistic, indefatigable, pompous, and stubborn – was conspicuous in every endeavour of his remarkably wide-ranging life.

Throughout his career Bryce was intensely involved in public-school issues. In 1875 he had advocated abolishing the government-funded dual Protestant and Roman Catholic school system in a series of letters to the Manitoba Free Press. He was subsequently elected to the Winnipeg Protestant Board of School Trustees, representing the North Ward from 1876 to 1879, and he acted as the first inspector of Winnipeg Protestant schools during the same period. He criticized the dual system for its inefficiency, ineffective administration, poor physical facilities, and lack of accountability to taxpayers. These complaints were not without substance, but his desire to prevent French-speaking Catholics from being taught in their mother tongue and receiving religious instruction in public schools was fuelled by a measure of sectarian and linguistic prejudice. It was also nourished by his firm belief, which he expressed in a letter published in the September 1893 issue of the Canadian Magazine, that public schools, rather than encouraging pluralism, should “rear up a homogeneous Canadian people.” He had welcomed the 1890 legislation, introduced by the provincial Liberal government of Thomas Greenway*, that replaced the dual system with the kind of non-sectarian system he had advocated, claiming that it was in the “national” interest. That same year he was appointed by Greenway to the provincial Advisory Board established to help the Department of Education and was in the thick of the controversy known as the Manitoba school question. He retired from the board in 1898.

Obeying the strictures that forbade clergy from taking a public role in electoral politics, Bryce was nevertheless active in the Liberal Party behind the scenes. When news of the Laurier–Greenway compromise [see Greenway; Sir Wilfrid Laurier*] of November 1896 was announced, Bryce must have been disappointed that there was latitude given for teaching in languages other than English and that religious instruction was permitted at the request of parents where numbers warranted. Nevertheless, he publicly defended the measure and assisted Laurier and the federal minister of the interior, Clifford Sifton*, by negotiating with Catholic leaders on some of the issues, such as the choice of bilingual textbooks, teaching certification for priests and nuns, and the wearing of ecclesiastical garb in the classroom. These negotiations were so politically sensitive that Bryce and Sifton communicated in cipher by telegram. Archbishop Adélard Langevin*’s firm opposition to the compromise, especially as it affected Winnipeg, where the Catholic population was decentralized, sent the school question into a protracted period of stalemate. Bryce’s departure from the Advisory Board in 1898 made him less useful as an intermediary, but he still occasionally acted in that role until Laurier’s defeat in 1911.

As the administrator of Manitoba College, Bryce had been instrumental in founding the University of Manitoba in 1877 [see Alexander Morris*]. The provincial act establishing the institution, however, limited its role to setting requirements for degrees and examining the students of its three affiliated denominational colleges. In addition to teaching English and science at Manitoba College, as of 1877 Bryce was a university examiner in zoology, botany, chemistry, astronomy, and geology.

Through the writings of Scottish evangelist and scientist Henry Drummond and British sociologist Benjamin Kidd, Bryce found a way to reconcile Christian faith with Darwin’s theory of natural selection, and he championed science with a clear conscience. He worked with the colleges to coordinate their hiring of professors to ensure that a wide range of science subjects would become available, allowing the university to begin offering an honours ba degree in natural science in 1888. Through membership in organizations such as the British Association for the Advancement of Science (BAAS) and the Institution Ethnographique of Paris, Bryce knew about the development of science faculties at other universities and lobbied for better teachers, a modernized curriculum, and improved laboratory facilities in Manitoba. He believed that these changes could be accomplished only if the university was allowed to offer courses, which required a change in legislation. Representatives of the Collège de Saint-Boniface, who regarded the expansion of the university’s role as an attack on the Catholic Church’s autonomy in higher education, resisted. Although the university act was amended in 1892 to permit teaching, the government did not appoint university professors, citing lack of money.

Around 1901 the university created three part-time lectureships in science. Bryce accepted one in biology and geology and agreed to become chairman of the science department. Acting in the latter capacity, he persuaded Lord Strathcona [Smith*] to make a substantial donation in 1904 to create six science professorships. The funding – and the termination of the lecturers’ contracts – allowed the institution to hire young men, most with recently earned phds, as professors in physics and crystallography, pathology and bacteriology, botany and geology, physiology and zoology, chemistry, and mathematics. Bryce let it be known that he would not apply for one of the new professorships, for which he was underqualified, and that he did not mind losing his lectureship since it helped enable the creation of a better science faculty. He resigned as chairman but continued working at Manitoba College as an English teacher and as the institution’s financial agent until retiring from education in 1909.

Despite losing his university positions in science in 1904, Bryce maintained his interest in the subject. His election to the Royal Society of Canada (RSC) in 1901 had been to its section for English literature, history, archaeology, and allied subjects, yet he kept up his science contacts, particularly as chair of the committee that brought the BAAS’s annual meeting to Winnipeg in 1909. He was named president of the RSC the next year and called in a political favour from Laurier: on behalf of the BAAS (whose ethnological survey committee he chaired) and supported by the RSC and the Archaeological Institute of America, Bryce proposed to create a division of anthropology within the Geological Survey of Canada, and the prime minister agreed to do so.

The early years of the 20th century brought honours to Bryce. In 1902 he had been elected moderator of the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church. The next year Knox College granted him an honorary . Although the Canadian Senate appointment that Bryce craved, and for which he actively campaigned, was not forthcoming, in 1909 Laurier named him to the Commission of Conservation [see James White*] and in 1910 to the royal commission on industrial training and technical education [see James Wilson Robertson*].

Bryce had been one of the founders of the Historical and Scientific Society of Manitoba in 1879 and served as its president from 1884 to 1887 and from 1905 to 1913. He had ventured into authorship around 1881. As busy as he was, he managed to publish nine books and more than 45 pamphlets on the history of the Canadian west, with side trips into its archaeology, ethnology, and geology. He wrote primarily about the fur-trade era, resuscitating the reputation of Lord Selkirk [Douglas*] and producing a history of the Hudson’s Bay Company. These works are of interest to modern readers only in that they reveal the ways in which a typical university-educated, Ontario-born Protestant of Bryce’s era viewed western Canada’s past.

Bryce presented a romanticized view of the fur-trade era. This has led some scholars, such as Doug Owram, to argue that he created a pre-1870 “golden age” based on the west’s historical roots being separate from those of central Canada, and that he did so out of disappointment with the treatment accorded to the west from the 1890s onward by a federal government in thrall to eastern interests. Although Bryce was annoyed with many federal policies, his faith that the west would ultimately achieve an equitable place in confederation was never shaken. If he had an underlying intention with his historical writing, it was to give the Anglo-Protestant elite a sense of the roots and rationale for their dominance in the west by emphasizing the continuity of British values, as first inculcated by the Hudson’s Bay Company and then carried on by the ascendant Canadian and British men of the railway era. Immigration from eastern Europe, labour unrest, and the tensions between Protestants and Catholics over the school question increasingly challenged Bryce’s view. His response was to heighten his rhetoric, speaking of Britain in almost mystical terms and, among fellow westerners, earnestly promoting a sense of identity that was based in large part on their status as subjects of the British empire.

Bryce’s health rapidly deteriorated after the death of his wife in 1920, and he moved in with his brother Peter in Ottawa. He died there in 1931, but his remains were returned to his beloved Manitoba, and he was buried in the Kildonan cemetery alongside his wife and son.

George Bryce is the author of “The Manitoba school question,” Canadian Magazine, 1 (March–October 1893): 511–16. An extensive bibliography on George Bryce can be found in the author’s “George Bryce: Manitoba scientist, churchman and historian, 1844–1931” (ma thesis, Univ. of Man., Winnipeg, 1983).

AM, MG 14, C15 #100 (George Bryce fonds, G. Griffith to G. Bryce, 7 May 1898). Ancestry.com, “Ontario, Canada, deaths and deaths overseas, 1869–1948,” Rev. George Bryce, 5 Aug. 1931; “Ontario, Canada, marriages, 1826–1938,” George Bryce and Marion Samuel, 17 Sept. 1872: www.ancestry.ca (consulted 13 July 2020). LAC, MG26-G, vol.564, p.152810-13, vol.627, p.170394-96, vol.629, p.170640-42; MG27-IID15, vol.39, p.26011, vol.187, p.150522. UCC, Man. and Northwestern Ont. Conference Arch. (Winnipeg), Rev. George Bryce fonds. Univ. of Man. Libraries, Dept. of Arch. and Special Coll., Ua 11 (University Council fonds), minutes, 1884–1904. Cyclopædia of Canadian biog. (Rose and Charlesworth), vol.1. H. W. Duckworth and Gordon Goldsborough, “Science comes to Manitoba,” Manitoba Hist. (Winnipeg), no.47 (spring/summer 2004): 2–16. Man., Statutes, 1892, c.49. Douglas Owram, Promise of Eden: the Canadian expansionist movement and the idea of the west, 1856–1900 (Toronto, 1980). Standard dict. of Canadian biog. (Roberts and Tunnell), vol.2.

Cite This Article

Catherine Macdonald, “BRYCE, GEORGE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 27, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/bryce_george_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/bryce_george_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Catherine Macdonald |

| Title of Article: | BRYCE, GEORGE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2022 |

| Year of revision: | 2022 |

| Access Date: | February 27, 2026 |