Source: Link

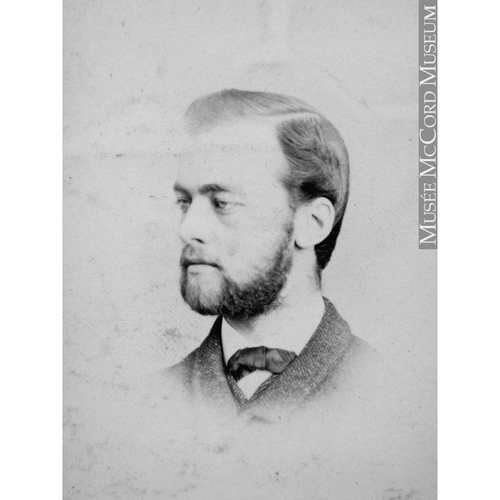

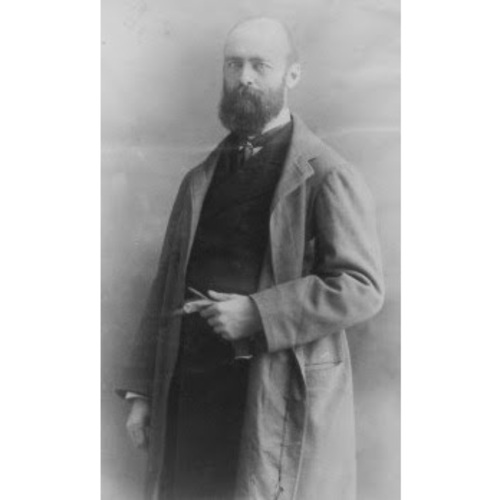

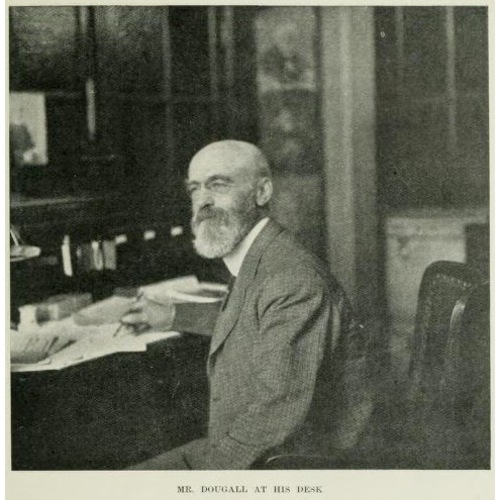

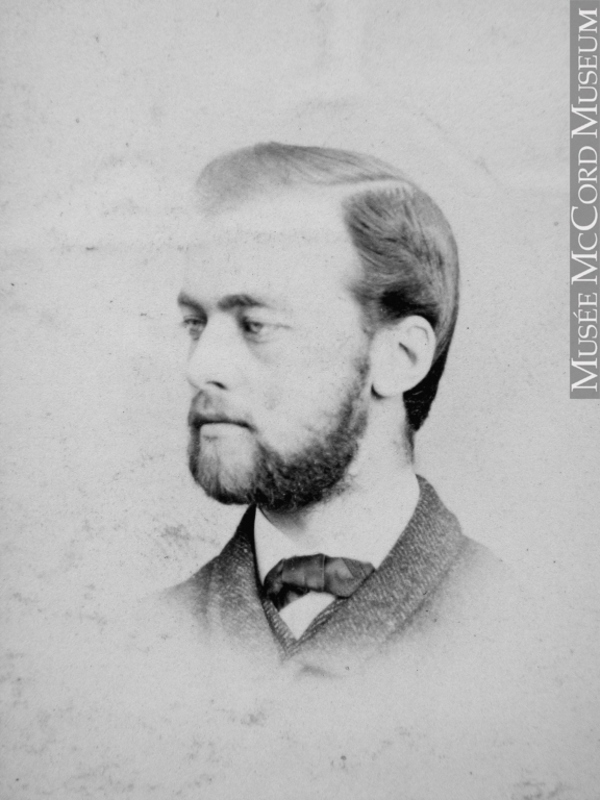

Dougall, John Redpath, journalist, editor, social reformer, and businessman; b. 17 Aug. 1841 in Montreal, eldest child of John Dougall* and Elizabeth Redpath; brother of Lily Dougall*; d. unmarried 18 Sept. 1934 in Westmount, Que.

John Redpath Dougall personified a major trend in Protestant thinking in Quebec. His career as a journalist and proponent of social causes, which lasted more than seven decades, spanned the transition from Victorian evangelical radicalism to early-20th-century pragmatism and the Social Gospel.

Dougall inherited his values from both sides of his family. His father was a leading temperance advocate, political reformer, and anti-Roman Catholic crusader. His mother was the eldest daughter of John Redpath*, a prominent businessman and leading figure in numerous Protestant charitable organizations, including the Montreal Protestant House of Industry and Refuge and the city’s Mechanics’ Institute. Both of Dougall’s parents had originally been members of the Church of Scotland but left it and joined the rigorous Zion Church, where they and their nine children worshipped. The importance of temperance and morality was the hallmark of Dougall’s upbringing and coloured his entire life.

His parents’ marriage also brought lucrative economic ties and social dividends. Born into wealth and privilege, Dougall, who often went by the initials J. R., was raised in a comfortable house called Ivy Green on the slopes of Mount Royal on land that had formed part of the country estate developed by his maternal grandfather into a fashionable Montreal suburb. He attended the elite High School of Montreal, where he received signal honours in literature, and then McGill College, where he obtained a ba in 1860 and an ma in 1867. He retained a connection with McGill as a senior fellow in arts, in which capacity he helped govern Quebec’s most influential educational, and leading secular Protestant, institution. In 1921 it would award him an honorary lld.

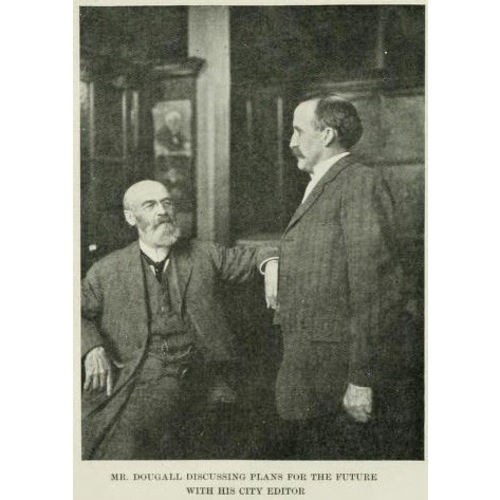

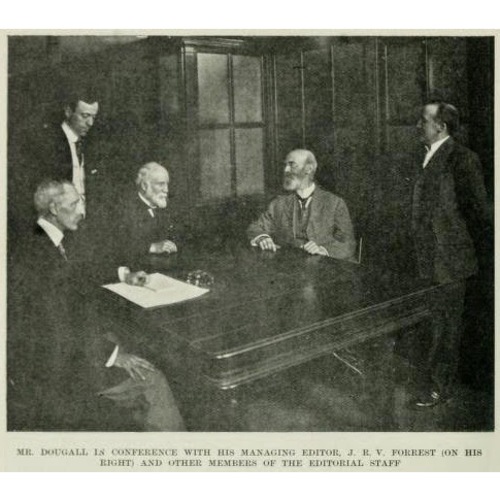

After finishing his bachelor’s degree, Dougall joined the staff of the weekly newspaper founded by his father, the Montreal Witness, the first issue of which had been published in 1846. A daily edition of the paper was added in 1860. J. R. reported on the American Civil War, which the Witness covered in great detail, taking a strong abolitionist stance, and he went to Washington to interview Abraham Lincoln at the Executive Mansion (later known as the White House). He travelled to Europe to cover the Franco-German War and the creation of France’s Third Republic. Upon J. R.’s return to Montreal in the spring of 1871, his father decided to start a new publication in New York and left the Witness in his son’s hands. J. R. remained the publisher and editor until 1913, when he sold the daily edition to the Telegraph Publishing Company Limited, which renamed it the Daily Telegraph and Daily Witness. He had control of the weekly version, however, until just before his death. In 1915 the weekly newspaper had a circulation of more than 22,000. About 1862 J. R. had opened a company with his father called John Dougall and Son, which printed the paper and their subsequent publications; it would operate until 1935, the year after Dougall’s death.

The company also owned and printed several other publications in Montreal. These included the second series of the Canadian Messenger, for which J. R. wrote. An evangelical, family-oriented magazine specializing in science, agriculture, and temperance issues, it first appeared in 1866. Renamed the Northern Messenger ten years later, it lasted until about 1935. There was also the New Dominion Monthly, a Canadian cultural review founded by the senior Dougall in 1867, which the company stopped issuing in 1879 owing to debt and competition. World Wide, established by J. R. in 1900, was a weekly reprint of topical editorials from newspapers around the world; it closed around 1937. Founded by J. R.’s nephew Frederick Eugene Dougall, Canadian Pictorial was a glossy magazine celebrating Canada’s landscape and prominent people, published by the family business between 1906 and 1916. It boasted of containing “between one and two thousand square inches of pictures in each issue.”

The Witness, however, was Dougall’s key publication. It was the mouthpiece for an evangelical strain of thought within Canadian Protestantism that advocated morality, propriety, honesty, self-reliance, liberty of thought and expression, and free trade. The Witness prided itself on being popular, affordable (the price for one copy had increased from one cent to five cents by the time of J. R.’s death), and always inclined to take the moral high ground in opposing privilege and vested interests. This stance was entirely consistent with its strong opposition to alcohol, the consumption of which, it was felt, led inevitably to addiction and consequently to the abandonment of the virtues the editors held so dear. Like the Puritans of previous centuries, the Witness disapproved of anything that seemed to smack of immorality; it refused to allow advertisements for theatres, hotels, lotteries, and sensational medicines, which filled the columns of most other papers, even though this decision meant turning away substantial revenue. Indeed, because of his principles, Dougall was eventually obliged to operate the publication at a loss, paying the production expenses and employees’ wages out of his own pocket.

The paper’s anti-Catholic position did not help expand its readership in Quebec. Protestant radicals had always criticized the power of the Catholic Church, but by the second half of the 19th century, with the rise of ultramontanism, their comments had become strident. After confederation many Protestants worried that they would suffer in an overwhelmingly Catholic Quebec, and the editors of the Witness took pains to underscore the dangers. The paper frequently promoted the work of Charles Chiniquy*, a former Catholic priest who had become a virulent opponent of the religion. Dougall, like his father, was not shy about painting Catholicism as the antithesis of virtue, arguing that it inspired intellectual laziness and encouraged people to rely on big church and big government instead of their own mettle. His constant attacks on the church infuriated its leaders, and in 1875 the bishop of Montreal, Ignace Bourget*, banned Catholics from buying or reading the Witness – an action that confirmed the editor’s worst fears even as it fuelled his ire. Towards the end of the century, as the Liberals expanded their influence within French Canada both federally and provincially, Protestant radicals came to find common cause with the party on issues such as church–state relations and free trade.

Aside from his printing and publishing ventures, Dougall was involved in a couple of other businesses. About 1891 he founded the Linotype Company in Montreal. In 1903 he patented a machine known as the Dougall linotype, but it was not a commercial success; the next year he sold the company. From 1897 until his death, he served as a director for the Sun Life Assurance Company of Canada.

Dougall’s well-known views made him a logical choice for president of the Quebec branch of the Dominion Alliance for the Total Suppression of the Liquor Traffic, a national temperance organization aiming to enforce universal Prohibition. This role brought him into contact with the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union and the world of religiously motivated reform known as the Social Gospel movement. Dougall’s own religious convictions and hostility towards corrupt power were translated into a concerted desire to save society’s impoverished masses from the effects of disease, crime, and vice. He denounced purveyors of liquor, notably Montreal’s Joe Beef [Charles McKiernan*], innkeeper and self-styled “Son of the People.” Beef sued the Witness for libel in 1880, but he lost the case.

Dougall had the practical objective of making institutions more efficient and improving the lot of the disadvantaged. In the 1880s he was a member of the Citizens’ League of Montreal, which sought to end the corruption associated with the liquor trade. For many years he was president of the Montreal Young Men’s Christian Association, an organization that would provide education and shelter to generations of young people. He championed the reform of Quebec’s schools, particularly as it was undertaken within the Protestant system early in the 20th century. A survey conducted by the Witness in 1906 pointed to widely perceived fears among Protestants that those in rural areas would be obliged to send their children to Catholic schools if their own system was not improved, and editorials acclaimed the 1907 opening of the School for Teachers at Macdonald College [see Sir William Christopher Macdonald*] in Sainte-Anne-de-Bellevue, which would revolutionize Protestant teacher training in Quebec.

Perhaps Dougall’s favourite cause was that of juvenile delinquents. As president of the Boys’ Home of Montreal in 1907, he promoted the creation of an institution in Shawbridge (Prévost), north of the city, where delinquent boys could live, receive an education, and learn a trade in a rural setting. He raised over $12,000 for the construction of the Boys’ Farm and Training School, which opened in 1908, and he continued to publicize it in the Witness. Dougall was later honoured when one of the residences was named after him. Generations of social workers and youth leaders owe much of their training to the boys’ farm and its counterparts across the country.

Dougall had advocated the union of Protestant churches as early as 1904, when he was a member of the joint committee on church union. He supported the creation of the United Church in 1925 [see Samuel Dwight Chown; Clarence Dunlop Mackinnon] although he argued that its power promised to be too centralized for his Congregationalist tastes. In later years Dougall was a member of Calvary Church, an offshoot of Zion Church, after the latter relocated to Westmount in the early 20th century.

After World War I, Dougall left Ivy Green, where he had lived for over 70 years, and moved to his nephew Frederick’s house on Belmont Avenue in Westmount. Hale into his nineties, apparently able to chop large quantities of wood at his summer retreat in Métis-sur-Mer, he fell ill early in 1934 and was obliged to surrender control of the Witness to Frederick. Four years later the newspaper, which was running a $10,000 deficit, would cease publication. Dougall died in 1934 a few weeks after his 93rd birthday. He was cremated at Mount Royal Cemetery and his ashes were interred in the family plot. Not surprisingly, newspapers across the country were quick to honour the veteran editor: the Gazette (Montreal) declared that he had been the dean of Montreal’s journalists and heralded him as a “true crusader.”

LAC, R7457-0-9. Mount Royal Cemetery (Montreal), Records, section L3. Gazette (Montreal), 19 Sept. 1934. Montreal Daily Star, 18 Sept. 1934. Montreal Daily Witness, 1871–1913. Montreal Herald, 18 Sept. 1934. Montreal Witness, 1861–1934. Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1898 and 1912). Owen Dawson, My story of the Boys’ Farm at Shawbridge: also, angels I have met ([Montreal], 1952). Dominion almanac (Montreal; annual suppl. to the Montreal Witness). L[ily] Dougall, When I was a little girl ([Edinburgh, 1896]). J. Hamelin et al., La presse québécoise. John Redpath Dougall, m.a., ll.d., doyen of Canadian journalism … ([New York, 1934?]). [Charles McKiernan], Joe Beef of Montreal, the son of the people ([Montreal, 1879]). [Zion Church], Brief annals of Zion Church, Montreal, from 1832 to 10th May, 1871: with lists of office-bearers and members, and reports for 1870 (Montreal, 1871).

Cite This Article

Roderick MacLeod, “DOUGALL, JOHN REDPATH,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 8, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/dougall_john_redpath_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/dougall_john_redpath_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Roderick MacLeod |

| Title of Article: | DOUGALL, JOHN REDPATH |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2021 |

| Year of revision: | 2021 |

| Access Date: | March 8, 2026 |