Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

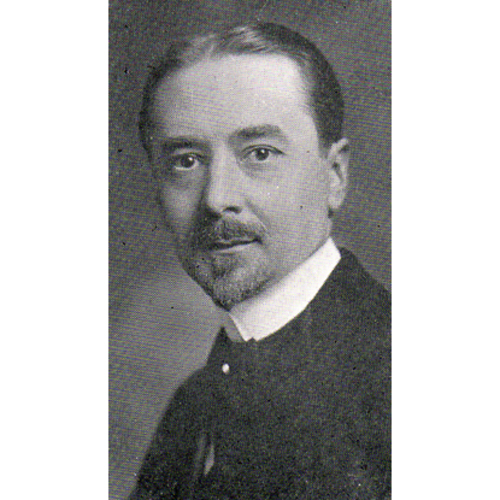

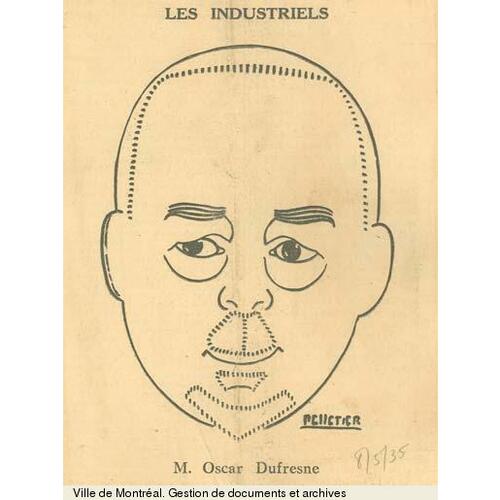

DUFRESNE, OSCAR (baptized Joseph-George-Évariste-Oscar Rivard-Dufresne), businessman and politician; b. 17 Oct. 1875 in La Visitation-de-la-Pointe-du-Lac (Trois-Rivières), Que., son of Thomas (J.‑B.‑Thomas) Dufresne (Rivard-Dufresne), a farmer, and Marie-Victoire Dussault; m. 16 May 1899 Laura-Alexandrina Pelletier (d. 27 Feb. 1935) in the parish of Saint-Jacques, Montreal, and they took a girl into their care; d. 1 May 1936 in Montreal.

Only 5 of the 11 children born to Oscar Dufresne’s parents reached adulthood. Oscar, the eldest, attended the village school from 1880 to 1883, and later the Collège Sainte-Anne in Yamachiche, from 1883 to 1887. In the autumn of 1887, while his father was mayor of Yamachiche, he studied in English for a year at the Trois-Rivières high school where he took a business course. With his father’s help, he subsequently got a job as a clerk in Montreal. There he worked for two years at Caverhill, Hughes and Company, and then at Bourgouin, Duchesneau and Company.

Oscar’s father gave him the task of taking the pulse of the business community in this large city where industrialization was on the rise. As the one in charge of sales for the shoes made by his wife, Marie-Victoire Dussault, who had been a shoemaker and designer for more than 25 years, Thomas wanted to settle in Montreal in order to expand his business. Oscar’s analysis was optimistic and convincing, so the rest of the family moved to the metropolis in June 1890 and opened the Fabrique Dufresne et Fils shoe factory in the fall. Oscar, aged 15, apprenticed as a shoe manufacturer in the family firm, which had to shut down in 1892 because of the unexpected departure of a partner. Two years later, with George Pellerin, his parents created the Pellerin et Dufresne shoe factory. Oscar was appointed assistant manager in 1895.

Market trends and the ease with which anglophone businessmen could obtain financing prompted Marie-Victoire Dussault to go into partnership around 1900 with the leather merchant Ralph Locke. Proximity to rail and sea transport and the tax exemptions and subsidies granted by the town of Maisonneuve (Montreal) to any entrepreneur who settled in the area persuaded Locke and Marie-Victoire Dussault to set up their factory there. It went into operation on 22 Aug. 1900. Oscar, who was bilingual and had been established in Montreal for more than ten years, immediately took over management of the factory and was to run it until his death. The following year the firm adopted the corporate name of Dufresne and Locke Limited.

Engaged in the business world, Dufresne nevertheless dreamed of starting a family. In May 1899 he had married Laura-Alexandrina Pelletier. Sometime between 1900 and 1901 he had a magnificent residence built at 434 Boulevard Pie-IX. The couple would have no descendants, but would take into their care a niece of Marie-Victoire Dussault, Laurette Normandin-Dufresne, born on 4 Jan. 1908, whose mother had died after giving birth.

In the summer of 1900 the town of Maisonneuve sent Dufresne, Napoléon Tétrault, and Joseph Daoust to Europe in search of business opportunities for leather and for Canadian footwear. The results were such that from 1903 Dufresne and Locke Limited exported to the Maghrib, and also to Cairo and Alexandria, thereby becoming the first North American company to ship goods to Egypt. The company had 400 employees and manufactured more than 300 pairs of shoes a day. The increase in production and the purchase of the Royal Shoe Company in 1904 dictated that the building be extended. The growth of the businesses in which Oscar was involved (the family also owned a tannery and a factory in Acton Vale that made farmers’ shoes) was remarkable: in 1902, the proprietors had spent $11,000 on salaries; in 1906, $120,000; and in 1911, $300,000. During this same period, the workforce doubled and output went from 350 pairs of shoes a day to 2,500. The commercial properties of the Dufresne family were valued in excess of $60,000 in 1911.

Although World War I was profitable for manufacturers of army boots, most owners of shoe companies saw their sales volumes plummet during the Great Depression of the 1930s. Dufresne and Locke Limited was no exception: the market would prove too small to absorb the costs of production and pay the salaries of its 500 workers in 1935. The company had to close its doors at the end of the decade.

During the period from 1910 to 1920, Maisonneuve, with 30 large enterprises, including 7 shoe firms, had become the largest industrial centre in suburban Montreal and the second largest in the province of Quebec. In 1909 the town’s management moved in a new direction when a municipal council was elected, which to all intents and purposes was run by the mayor, Alexandre Michaud, and Dufresne; the latter would be a councillor until 1915 and, in addition, the chair of the finance committee from 1910 to 1914. The team embarked on sizeable civic projects, thanks, in particular, to the work of Marius, Oscar’s brother, who was the town’s engineer from 1910 to 1918.

The first prestigious edifice built in Maisonneuve was a more spacious town hall with grandiose architecture in the beaux-arts style, erected at the corner of Rue Ontario and Boulevard Pie-IX (1910–12), and designed by the architect Joseph-Cajetan Dufort. In 1911 the town council supported the city of Montreal in its desire to host the 1917 world’s fair and offered the required land. World War I was to frustrate the project on which Maisonneuve spent considerable sums. The decision to build a large market in 1913 on the median of the thoroughfare that would become Avenue Morgan was taken the following year. Marius drew up the plans for this beaux-arts–style institution, which would be judged one of the major agricultural markets of the province and would also serve as a place for meetings and festivities. As well, the town council saw to the development of Boulevard Pie-IX and Avenue Morgan which was carried out from 1912 to 1915. A police and fire station (1914–15) and public baths for the hygienic needs of the population (1914–16) were also erected. The Maisonneuve public bath and gymnasium, a work of Marius inspired by New York City’s Grand Central Terminal, was considered one of the most attractive in North America. At the end of 1914 Dufresne was appointed chairman of the Maisonneuve Park Commission, whose mandate was to create a park for cultural and sporting activities where Dufresne envisioned cafés, art galleries, museums, a library, artificial lakes, an amphitheatre, an autodrome, a racecourse, hotels, Japanese gardens, and a casino. The scale and production costs of the park were to limit its realization.

The capital invested in all these projects increased Maisonneuve’s debts and, because of World War I, the town saw its revenues diminish at the same time as its capacity to repay its loans. Consequently in 1918 the provincial government forced the city of Montreal to annex Maisonneuve and assume its financial obligations.

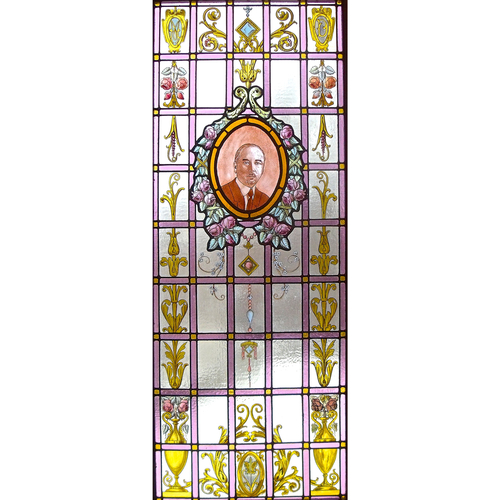

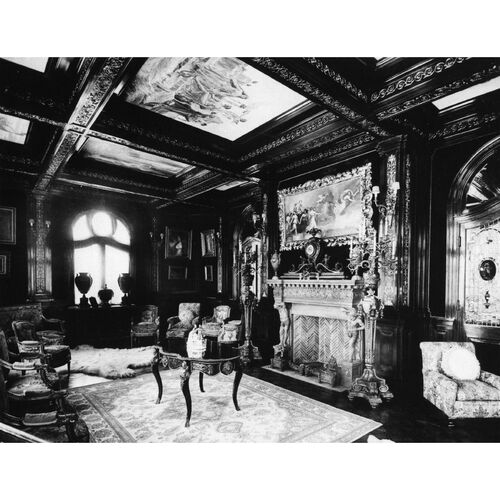

Meanwhile, in 1914 Dufresne had decided to have a house built west of Pie-IX, on Sherbrooke Street, from where he had a panoramic view of the river. Marius, who was to live there with him, drew up, with Jules Renard, the plans for this 40-room residence of French neoclassical style and beaux-arts inspiration. The dwelling, which was divided into two equal areas by a common wall, was modelled on the Petit Trianon in Versailles, France, and its facade, covered by Indiana limestone, measured about 133 feet. Oscar and his wife occupied the east part, which was decorated by Guido Nincheri, a painter and glazier. The interior, Edwardian inspired, borrowed elements from different styles: Empire, Italian Renaissance, Louis XV, and Gothic. Furnishings and tapestries were imported from France, the marble from Italy, and the wood from Japan. The decoration of Marius’s rooms was mainly the work of Jean-Alfred Faniel. Because of its opulence and the purity of its lines, this residence, which would be known as the Château Dufresne from the 1970s, and then as the Musée du Château Dufresne in 1998, is among the most beautiful of Montreal’s architectural jewels.

A prominent industrialist, Dufresne was also a man whose backing was ardently sought, a philanthropist, and a patron of the arts. On 29 March 1913, yielding to pressure from Henri Bourassa*, Dufresne had agreed to sit on the board of directors of Le Devoir. In 1924 he eliminated the deficit of this Montreal newspaper by digging into his own pockets. He was a director of Sun Trust, Limitée, the Slater Shoe Company Limited, and the Paint Products Company Limited. He was the president of the Librairie Beauchemin Limitée and the Imprimerie Populaire Limitée. He chaired the boards of governors of Notre-Dame Hospital and of Dufresne Construction Company Limited, which in 1925 erected the supports and approaches of the northern section of the future Jacques Cartier Bridge. He sat on the boards of directors of the Banque Nationale, the Banque Provinciale du Canada, Perfection Robert, the Montreal Tramways and Power Company Limited, and the Canadian Military Stores and Wares Commission. He was a member of the administration committee of the Université de Montréal and the founder and president of the Société Canadienne d’Opérette Incorporée, which he supported with numerous donations. He lent his name and gave money to the Canadian National Institute for the Blind. A friend of Brother Marie-Victorin [Conrad Kirouac*], with whom he dreamed of building a botanical garden opposite his house, Dufresne mused over keeping schoolchildren occupied during the summer holidays. He called on the expertise of Marie-Victorin to organize botanical competitions. They both sought the collaboration of Bourassa so that these events would be advertised in Le Devoir.

Oscar Dufresne died of a heart attack on 1 May 1936 and, according to an article in Le Devoir on 6 May, was given a funeral worthy of a “prince of charity.” Thirteen carriages laden with flowers and nearly 3,000 people accompanied the hearse to Saint-Jean-Baptiste-de-Lasalle church in Montreal. His remains were taken to Notre-Dame-des-Neiges cemetery. Public tributes in the newspapers after his death presented Dufresne as a hard worker with broad horizons. His generosity, discretion and humility, business sense, and passion for beauty and progress had made him a man of solid accomplishment.

In addition to the sources mentioned below, the following newspapers have been consulted: Le Devoir, La Patrie, and La Presse. More information on the history of Maisonneuve and its amalgamation with Montreal can be found in P.‑A. Linteau, Maisonneuve ou comment des promoteurs fabriquent une ville, 1883–1918 (Montréal, 1981).

Atelier d’Histoire d’Hochelaga-Maisonneuve, Centre de documentation (Montréal). BANQ-CAM, CA601-S21; CE601-S33, 16 mai 1899; CN601-S573. BANQ-MCQ, CE401-S14, 18 oct. 1875. VM-SA, P25. Le Devoir, 2 mai 1936. Guy Bourassa, “Les élites politiques de Montréal: de l’aristocratie à la démocratie,” in Le personnel politique québécois, Richard Desrosiers, édit. ([Montréal, 1972]), 117–42. François De Lagrave et le Comité du 250e Anniversaire, Pointe-du-Lac, 1738–1988 (Pointe-du-Lac [Trois-Rivières, Québec], 1988). André Dufresne, De Rivard à Dufresne … une histoire de famille (Montréal, 2006). Pauline Gill, La cordonnière (Montréal, 1998); Les fils de la cordonnière (Montréal, 2003); Le testament de la cordonnière (Montréal, 2000). Industries of Canada, city of Montreal, historical and descriptive review, leading firms and moneyed institutions (Montreal, 1886). Linteau, Hist. de Montréal. P.‑A. Linteau et al., Histoire du Québec contemporain (2v., Montréal, 1979–86). J.‑A. Pellerin, Yamachiche et son histoire, [1672–1978] ([Trois-Rivières], 1980). Guy Pinard, Montréal: son histoire, son architecture (6v. parus, Montréal, 1986– ), 1: 251–56. Fernande Roy, Progrès, harmonie, liberté: le libéralisme des milieux d’affaires francophones de Montréal au tournant du siècle (Montréal, 1988). Rumilly, Hist. de la prov. de Québec; Hist. de Montréal, vols.2–3. Carmen Soucy-Roy, “Le quartier Ste-Marie, 1850–1900” (mémoire de m.a., univ. du Québec à Montréal, 1977).

Cite This Article

Pauline Gill, “DUFRESNE, OSCAR (baptized Joseph-George-Évariste-Oscar Rivard-Dufresne),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 1, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/dufresne_oscar_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/dufresne_oscar_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Pauline Gill |

| Title of Article: | DUFRESNE, OSCAR (baptized Joseph-George-Évariste-Oscar Rivard-Dufresne) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2017 |

| Year of revision: | 2017 |

| Access Date: | March 1, 2026 |