Source: Link

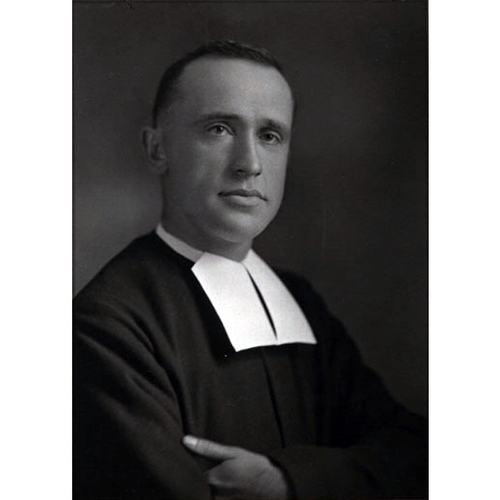

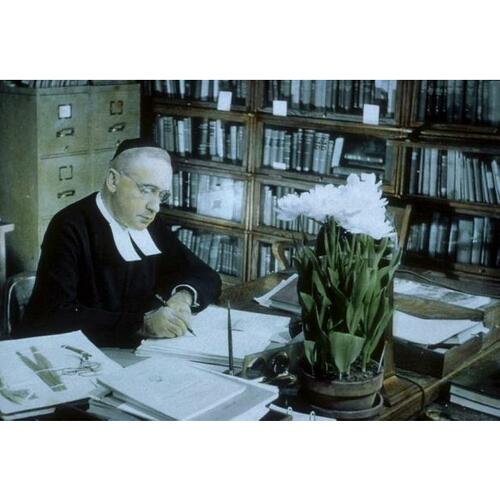

KIROUAC, CONRAD (baptized Joseph-Cyrille-Conrad), named Brother Marie-Victorin, member of the Brothers of the Christian Schools, educator, botanist, and author; b. 3 April 1885 in Kingsey Falls, Que., son of Cyrille Kirouac and Philomène Luneau; d. in a highway accident 15 July 1944 near Saint-Hyacinthe, Que.

Conrad Kirouac was the son of a well-to-do merchant in the Eastern Townships. He would have five sisters and five brothers, but the latter would all die in early childhood; he himself would suffer from terrible ill health that seriously hampered his activities. When he was five years old his family moved to Saint-Sauveur ward in the Lower Town of Quebec, where his father joined F. Kirouac et Fils, a flour and grain business founded by François Kirouac, Conrad’s grandfather. Conrad took all his schooling with the Brothers of the Christian Schools, first at the elementary school in Saint-Sauveur, and then from 1898 at the Académie Commerciale de Québec. His teachers made a strong impression on him, and when he finished his studies, standing first in his class, he decided to enter the community of the Christian Brothers despite the opposition of his father, who wanted him to become a merchant, or at the very least a priest. On 8 June 1901 he was admitted to Mont-de-La-Salle, the brothers’ novitiate in Maisonneuve (Montreal). In August he adopted his religious name, Marie-Victorin. Mont-de-La-Salle was on the exact site of the future Montreal Botanical Garden, which Marie-Victorin was to found 30 years later.

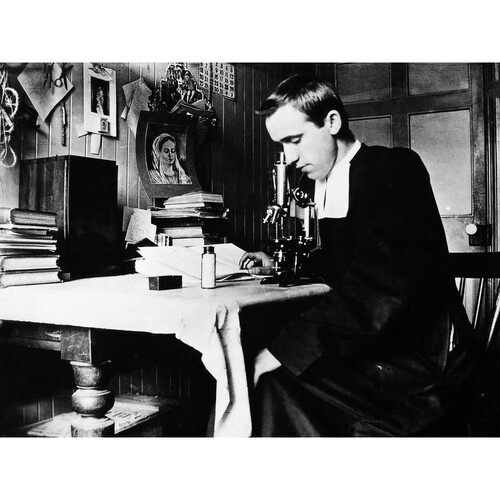

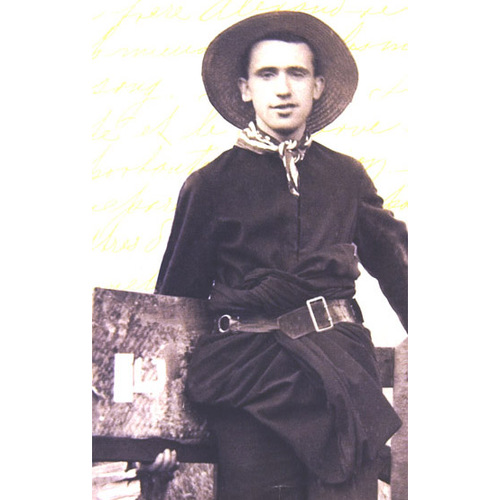

In the spring of 1903 Marie-Victorin received his first teaching appointment to the brothers’ school in Saint-Jérôme. He was assigned a fifth-year class, but was then transferred to a fourth-year class because of his difficulties as a new instructor. On 7 June, with the summer holidays drawing near, Marie-Victorin started a diary that he would continue to keep until 1920. Afflicted with tuberculosis, he suffered his first bout of haemorrhaging in December. It was during his convalescence that he made the great discovery of his life: botany. Armed with an old book, Flore canadienne … by Abbé Léon Provancher*, published in Quebec City in 1862, he explored the surrounding area, starting in May 1904, in order to begin learning about plants. A true passion was born.

Soon sufficiently recovered, Marie-Victorin spent a couple of months in Westmount (from 31 August to 23 November) and in December was assigned to the Collège Commercial et Industriel at Longueuil, where his star rose rapidly. In addition to teaching almost every subject, especially English, French composition, geometry, and algebra, he took on several extracurricular activities despite his frail health. He organized two discussion groups for students, enrolled them in the Association Catholique de la Jeunesse Canadienne-Française, wrote and produced plays, and mounted campaigns to stimulate the national pride of French Canadians and love of the French language. Some of his plays, including Charles Lemoyne, which was written to honour the founder of Longueuil and was performed for the first time in May 1910, and Peuple sans histoire (1918), which denounced the ill-famed Lord Durham [Lambton*], enjoyed real success far beyond the bounds of the school.

At the same time, under the pseudonym M. son Pays, Marie-Victorin contributed to the column “Billet du soir” in the newspaper Le Devoir from 10 Sept. 1915 to 26 June 1916. A superb stylist, he sang the praises of nature and the glory of French Canadian traditions. Two stories he submitted to a competition organized by the Société Saint-Jean-Baptiste de Montréal won prizes: “La croix de Saint-Norbert” in 1916 and “La corvée des Hamel” in 1917. Since his stories were very well received, he published nine of them in a single volume in 1919, under the title Récits laurentiens. The following year he brought out Croquis laurentiens. These two works, which were illustrated by Edmond-Joseph Massicotte* and published in Montreal, flaunted his ambition to arouse in French Canadians both national pride and the desire to take possession of their land. At the same time, they revealed nostalgia for a simpler era when the Roman Catholic clergy were universally respected and guided their flocks for the good of all.

If as an author he willingly turned towards the past, as a self-taught botanist he would always concentrate on building the present and preparing for the future. A voracious reader, by March 1906 he had devoured every issue of Le Naturaliste canadien published since 1871. Thus he made his entry directly into the ever-changing world of contemporary science and learned about recent discoveries, ongoing controversies, and still-unsolved problems. As well, he gradually familiarized himself with the identification of plants and the principles of classification. Brother Rolland-Germain, a sturdy Burgundian who had come from his native France in 1905, was his guide at the outset and then became a diligent co-worker. Taking advantage of every free moment to collect plants in the Montreal region, Marie-Victorin felt sufficiently confident by 1908 to write his first scientific article, which Le Naturaliste canadien published in its May issue. Significantly, it was entitled “Addition à la flore d’Amérique.” In May of the following year a second piece, “Contribution à l’étude de la flore de la province de Québec,” appeared in the same publication. He now evinced a slowly growing urge to revise the catalogue of plants in French Canada from beginning to end. Though just a beginner, Marie-Victorin fully understood the extent to which the science of botany was lacking in the province of Quebec. After an outstanding start, thanks to the great explorers of New France, interest had gradually waned, and since the work of Abbé Provancher little or nothing had been done.

Far from letting himself be paralysed by this barrenness, Marie-Victorin undertook a program of exchanging samples and information with recognized specialists around the world. Among these correspondents he found his mentor, the famous American botanist Merritt Lyndon Fernald, who had explored much of the province of Quebec. Fernald agreed to take his young colleague under his wing, and this influence would pervade his protégé’s work. Also significant was his meeting in 1912 with Francis Ernest Lloyd, a professor of botany at McGill University. An immediate friendship sprang up between the two men. Lloyd lent Marie-Victorin Principles of breeding … (Boston, 1907) by the American agronomist Eugene Davenport. Curiously, it was in this treatise on livestock breeding that Marie-Victorin gleaned knowledge about the science of genetics, which was then still in its infancy.

Initiated by the Moravian monk Gregor Johann Mendel around 1865, genetics had been in decline and then in 1900 was revived by the work of the Dutch botanist Hugo De Vries. For Marie-Victorin this science was a discovery of capital importance not only for his future work, but also immediately, because scarcely had he become aware of this new discipline when he saw in it a decisive weapon against the bête noire of the Catholic Church: Charles Darwin’s theory of natural selection. Marie-Victorin thought he had found a flaw. Darwin postulated that the modifications observed in the succession of species appeared only in the long term, and that the survival of the fittest is an extremely slow and lengthy process. Now, as De Vries and others had clearly demonstrated, genetics brought to light some very rapid modifications, mutations that appeared from one generation to the next. In June 1913 Marie-Victorin published, again in Le Naturaliste canadien, “Notes sur deux cas d’hybridisme naturel: mendélisme et darwinisme.” With this article he believed he had delivered a fatal blow to Darwinism. His reasoning was simple. Genetics presents an empirical science verifiable by various experiments, but there will never be an experiment to confirm the truth of natural selection. Consequently, the latter theory must fade away. Here he showed an aplomb he never lost.

Meanwhile, Marie-Victorin continued to ponder his plan to undertake a botanical survey of French Canada. When the Quebec Society for the Protection of Plants from Insects and Fungous Diseases announced, in its annual report for 1911–12, that it was considering reprinting Abbé Provancher’s Flore canadienne, Marie-Victorin rebelled against this idea because since the end of the 19th century nomenclature had evolved, previously inaccessible regions had been opened up, and new species had been recorded. What was needed, in his view, was a new plant guide based on modern scientific principles. He did not make an official announcement to this effect, but the society quietly abandoned its project.

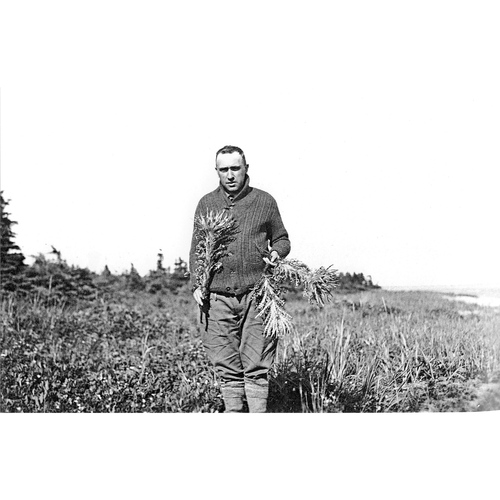

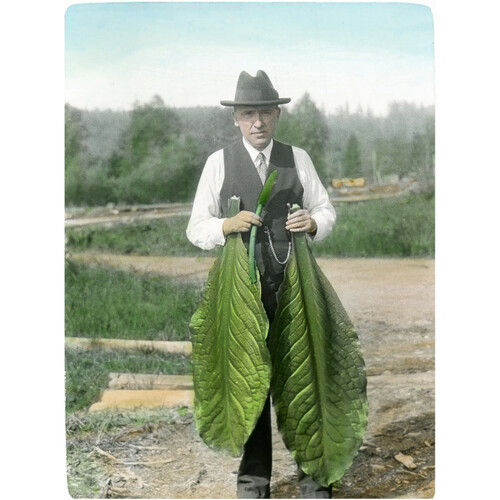

Marie-Victorin breathed more easily and tackled his botanical project more systematically, for the inventory was far from finished. For him, to give a name to what makes up a country was truly to take possession of it. Heretofore, it had been mainly the English and Americans who undertook to explore the territory of the province, a situation he deemed in urgent need of correction. He went on more and more excursions during which he collected, classified, and listed species. Sometimes, when he was able to identify previously unknown species through perseverance, he even named them. For instance, in the summer of 1913 (most of his exploring was done during the summer holidays since he was a teacher), he went with Brother Rolland-Germain to Témiscouata. An area still unexplored by botanists, it yielded them some 50 new species. Marie-Victorin thus had an opportunity to send specimens to Fernald, both to confirm his identifications and to tell him about his plan for a new Quebec plant guide. Fernald congratulated him, but also warned that what he had in mind would be a very large-scale work, scarcely conceivable as an initiative by one person alone. At the same time, Fernald continued to welcome his explorations very warmly, and they stepped up their scientific collaboration. In 1915 and 1916 Marie-Victorin published in Le Naturaliste canadien a series of articles about his expeditions and then organized them in a single volume. Entitled La flore du Témiscouata: mémoire sur une nouvelle exploration botanique de ce comté de la province de Québec, it came out in Quebec City in 1916, the year he won a prize for “La croix de Saint-Norbert.” The collection was the first work devoted to this unstudied region. It not only foreshadowed the forthcoming general plant guide, but also brought Marie-Victorin his earliest renown in the sciences. His fame grew in 1918 when he published “La flore de la province de Québec” in the Revue trimestrielle canadienne (Montréal).

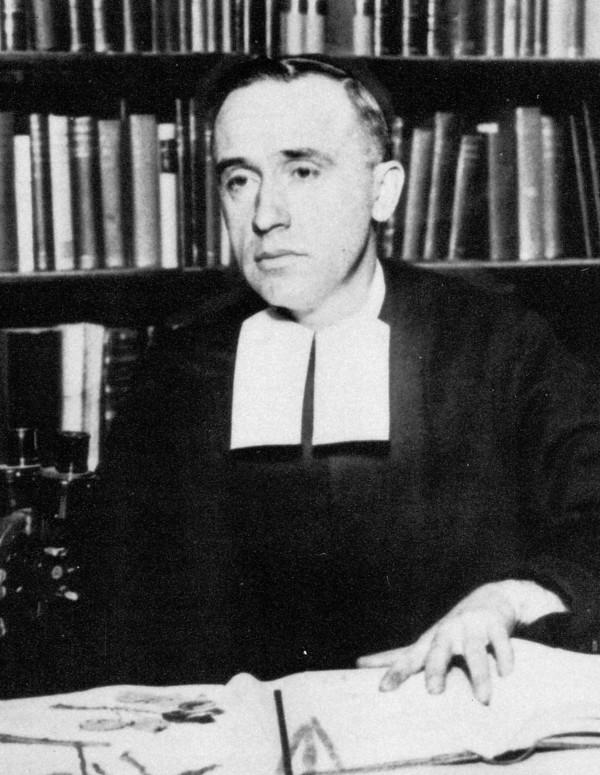

The beginning of the 1920s brought great changes to Marie-Victorin’s life. Stifling under the yoke of the Université Laval in Quebec City for too long, the Montreal campus had won full autonomy in 1919 and became the Université de Montréal. Quickly and efficiently, it set up faculties and chairs of instruction in preparation for the beginning of classes in September 1920. For the chair of botany, only one name came to everyone’s mind: Marie-Victorin. No matter that he had no university degree and had educated himself by whatever means came to hand – he had already shown proof of his strengths. Since 1908 he had published close to 40 notes and articles, a scientific work on the flora of Quebec, and some 60 articles for the general reader. Moreover, he was already recognized by his peers abroad and by people at home. The university immediately made him an associate professor. Very attached to his students at the secondary level, Marie-Victorin continued to teach them on a half-time basis at the school in Longueuil until 1928, for his new status did not make him lose sight of his main concern: to raise the level of education of his own people, regardless of their academic attainment. He could no longer accept the prevailing spirit of resignation, in which one settled for blissfully preparing for eternal life, leaving control of temporal life to the “Anglais.” It was time to shake off the chains, “or else,” he would say in 1940, “we will never be a people worthy of the name and we will always remain a tribe of hacks and servants, a caste of drones in the hive of civilized humanity.”

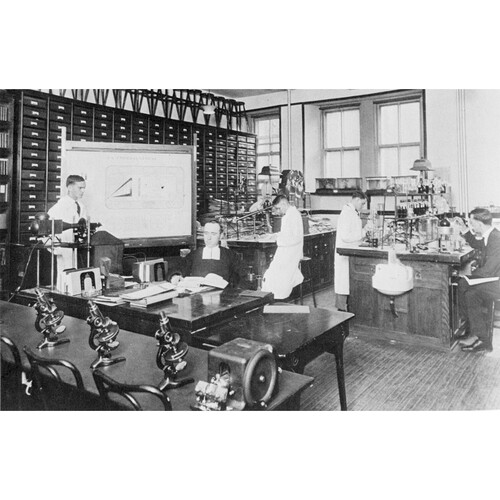

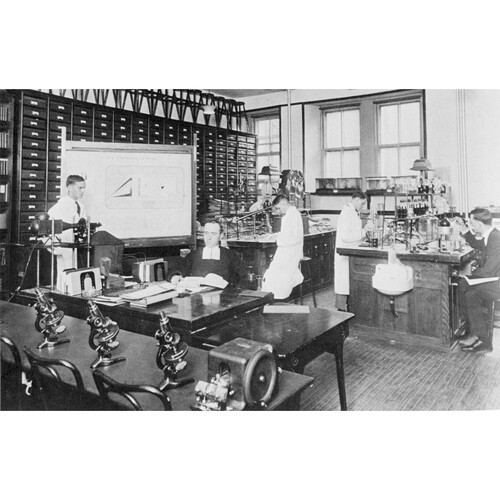

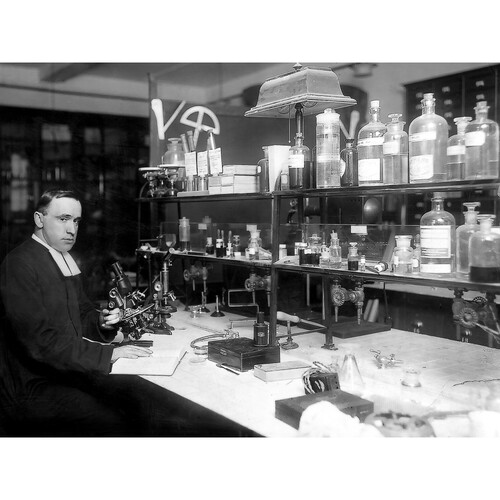

Marie-Victorin’s university career was also his most productive period. Installed in rather makeshift fashion in the basement of the university on Rue Saint-Denis downtown, he both taught and introduced students to research, for to him the two were absolutely inseparable. (In 1931 he would rename his Laboratoire de Botanique an institute to draw attention to this vital connection.) In 1921 he read some works by Father Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, a Jesuit at odds with his order, which enabled him to understand that the theory of evolution was not at all in conflict with the teachings of the church. It would be many years, however, before he would publicly acknowledge this new conviction. He did so in 1929, when he was abroad, as a delegate to the convention of the British Association for the Advancement of Science at the University of Cape Town, South Africa. On 22 July he gave a presentation in English on the evidence for evolution in the flora of the American northeast. It was the first time the word “evolution” appeared in his writings.

Meanwhile, in 1922, having received a dispensation from taking all the courses normally associated with the award of a phd, Marie-Victorin successfully defended his doctoral dissertation on ferns, which was entitled “Les filicinées du Québec.” He now became a tenured professor. He was also one of the founders of the Association Canadienne-Française pour l’Avancement des Sciences (ACFAS) in 1923 and its first secretary, with Dr Léo-Erol Pariseau as the first president. That year he also set up the Société Canadienne d’Histoire Naturelle and made it the botanical section of the ACFAS. He served as its secretary and then as its president from 1925 to 1940. In 1931, on his initiative, the society would create the Cercles des Jeunes Naturalistes, founded by Brother Adrien Rivard and destined to be a resounding success. All these organizations obviously fit into his unceasing campaign to combine science and general knowledge at every level and for people of all ages.

Other causes would also continue to make demands on Marie-Victorin. In 1924 he was admitted to the Royal Society of Canada, but only to the literary section. He perceived this as a message that, in the eyes of the “Anglais,” French Canadians were worthy of only the literary ghetto and could not aspire to the scientific sections. It would take three years of skirmishing to get his credentials recognized and be admitted into the biology section, of which he would moreover be president in 1933–34.

In 1930, with Marie-Victorin as president, the Société Canadienne d’Histoire Naturelle founded the Association du Jardin Botanique de Montréal. His main struggle had now begun. It seemed incongruous to him that a city the size of Montreal should be without such a facility. He hounded the authorities and in 1931, in the midst of the worldwide Great Depression, he persuaded the city to found the Montreal Botanical Garden, an enterprise with the twofold aim of attracting tourists and carrying on research and teaching. When Maurice Le Noblet Duplessis* became premier on 17 Aug. 1936, a new era of generous funding began for the garden, and in June 1939 Marie-Victorin achieved a masterstroke. He obtained permission from the university to establish his institute in the botanical garden, rather than letting it stagnate until the university building on Mount Royal was finished. In crisis and threatened with closure, the university grudgingly agreed to what it considered a defection. Even though Marie-Victorin stood valiantly by the university’s side in the struggle, the coolness created by this move was slow to disappear. Moreover, Marie-Victorin had to support “his” garden single-handed for years, since the Liberals, who under Adélard Godbout* were elected on 25 Oct. 1939, gradually stopped providing financial support. Only the return to power of Duplessis on 8 Aug. 1944 would ensure the continued existence of this establishment, which then took its place among the great botanical gardens of the world.

Fortunately, all this organizational activity did not harm Marie-Victorin’s research career in any way. In April 1935 he had finally realized his lifelong dream: to publish a new inventory of the plants of Quebec, which he entitled Flore laurentienne, and thereby enable his fellow French Canadians to become informed about their own land and take possession of it. Produced with the help of many colleagues, including Brother Alexandre, who was responsible for the illustrations, as well as Jules Brunel, Jacques Rousseau*, and Marcelle Gauvreau, three especially close associates, the book was unique at the time. Its 917 pages of unparalleled descriptive language brought together all the available data about 1,917 plants found in the inhabited part of the province of Quebec, including not only botanical information but also genetic, encyclopedic, medical, and ethnological particulars wherever possible.

Flore laurentienne is without question Marie-Victorin’s most outstanding work, but there are others, including Flore de l’Anticosti-Minganie, which was based on the many expeditions he had made in this region between 1924 and 1928 and was released posthumously in Montreal in 1969. In 1942 and 1944 Marie-Victorin also published his impressive “Itinéraires botaniques dans l’île de Cuba” (Montreal) in the Contributions de l’Institut botanique. (A third instalment would come out in 1956.) Since 1938, enfeebled by heart and pulmonary problems, he had been unable to endure Montreal winters and had spent the cold season on islands in the south, in Cuba for the most part, where, with his colleague Brother Léon, he devoted himself to systematic study of the local flora. His reputation, which had earned him many prizes and distinctions, now spread beyond Quebec, the United States, and Europe to the Caribbean. But Marie-Victorin had exerted himself so much that he was now completely exhausted. He was only distantly involved with the day-to-day operations of the botanical garden and institute and depended increasingly on Brunel and Rousseau for the conduct of current business. In fact, hardly anything stimulated him now but botanical excursions. On 15 July 1944 he organized an outing with a few friends to find a small, extremely rare fern reported by an American explorer to be in the Bois-Francs region. On the way home, their automobile was involved in a collision near Saint-Hyacinthe. Although Marie-Victorin and his friends sustained only minor injuries, he suffered a heart attack and died on the way to the hospital.

Marie-Victorin’s death touched off an unusual wave of emotion, not only in Quebec, but also throughout North America and in Europe. A giant was gone, and no one who had known him wanted to miss the opportunity to salute his accomplishments. In addition to Flore laurentienne and the Montreal Botanical Garden and Institut de Botanique, there had been his never-ending struggle to make science part of general knowledge; his crusades in favour of the pure sciences and the intermingling of disciplines; his campaign, from 1937, to create the Institut de Géologie at the Université de Montréal; his pressure on Quebec writers to find their inspiration in local landscapes rather than conjure up European trees and animals not found in North America; his efforts to improve the scientific training of teachers at every level, especially by the creation in 1930 of summer courses, which would be called the École de la Route; the programs known as Radio-Collège, transmitted by the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation to listeners in every corner of the province from 1941; his exceptional literary talent; and his coining of many new words (including the place name Minganie and the term Madelinot for a resident or native of the Îles de la Madeleine).

This enormous work was carried out by a weak, sickly individual. Despite a robust appearance, Marie-Victorin had a surprisingly limp handshake. He also had a remarkably casual lifestyle. Born into an affluent family and completely taken care of by his community, he showed so little concern for material things that the appropriateness of his attire had to be closely monitored. On the other hand, there was nothing casual about his approach to the tasks he undertook. He tolerated no dilettantism from those around him and expected his assistants to show a missionary zeal. He could not stand to have anyone get in his way, and those who had the effrontery to attempt to harm “his” garden felt his wrath, as did those who wanted to confine French Canadians to the “delights” of the humanities. In a Quebec totally imbued with religion and morality, he was also criticized for his very liberal attitude with regard to sexuality. He had, after all, introduced sex-education courses at the Collège de Longueuil. In addition, he had always insisted that the exact terms be used for the sexual organs and their functions. Some even thought that his religious calling was threatened by his relationship (perhaps sexual) with his assistant Marcelle Gauvreau. All his life he had known the inhuman bleakness of the vow of chastity and he had written copiously about the subject in his diary. He would respond to those who, offended by his candour, insulted him, feeling very disappointed by their petty views, which were often expressed in euphemistic, vulgar, and ignorant terms. His public stance was in fact based on a secretive, frankly even illicit approach. A scientist through and through, Marie-Victorin had seen in human sexuality an entire unexplored continent and had decided to devote himself to its systematic study. However, in view of the prurient frenzy of the 1930s and ’40s, he informed only his confidante, Marcelle Gauvreau, of his underground activities, going so far as to invite her to practise various forms of stimulation on herself in order to note their physiological effects. A forerunner, but a cautious one, he did not publish anything on these matters. He confined himself to surreptitiously exchanging a large amount of correspondence with Gauvreau, which he called the “biological letters.”

Given this background, combined with an outspokenness that was unusual in that era, Marie-Victorin was often in the line of sight of many superiors, especially since he had never really submitted to the discipline of his community and had been permitted, as an exception, to inherit his father’s estate and to have his own car and driver. So much eccentricity in such a famous person could not elicit universal admiration, and naturally Marie-Victorin also had his detractors.

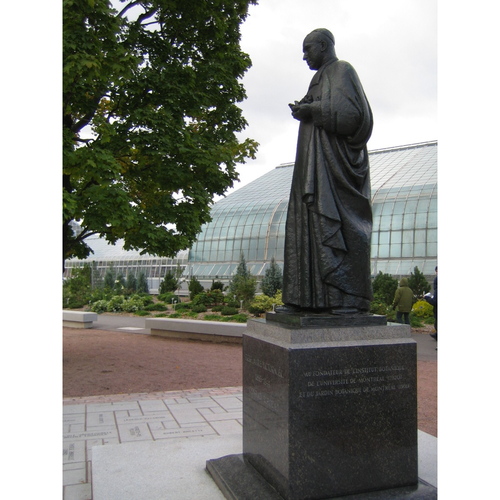

However, his reputation did not suffer in the least, and in 1954 Premier Duplessis unveiled, at the entrance to the Montreal Botanical Garden, a statue of Brother Marie-Victorin by the renowned sculptor Sylvia Daoust* as a tangible mark of gratitude for the public’s immense debt to him.

The journal of Conrad Kirouac, named Brother Marie-Victorin, has been published as Mon miroir: journaux intimes, 1903–1920, Gilles Beaudet et Lucie Jasmin, édit. (Saint-Laurent [Montréal], 2004). His letters, all addressed to his eldest sister Adelcie, named Marie-des-Anges, have been collected under the title Confidence et combat: lettres (1924–1944) (Montréal, 1969). His 1940 speech to the Société Canadienne d’Histoire Naturelle, “L’Institut Botanique: vingt ans au service de la science et du pays,” has been reproduced in Rev. trimestrielle canadienne (Montréal), 26 (1940): 274–93, 432–45; 27 (1941): 76–90. A complete list of some 300 writings by Marie-Victorin can be found under “Collections documentaires” on the website of the Montreal Botanical Garden at www2.ville.montreal.qc.ca/jardin/biblio/numerique/numerique.htm (consulted 19 Feb. 2010).

Documents pertaining to Marie-Victorin are located in several places. The Div. des arch. of the Univ. de Montréal is the main depository of the L’Institut Botanique de Montréal fonds (E 118). On the other hand, the fonds of l’ACFAS (17P), the Soc. Canadienne d’Hist. Naturelle (15P), and Marcelle-Gauvreau (7P) have been gathered together by the Service des arch. et de gestion des doc. of the Univ. du Québec à Montréal. Conrad Kirouac’s baptismal certificate (CE403-S1, 5 avril 1885) is at the Centre d’arch. de la Mauricie et du Centre-du-Québec of the Bibliothèque et Arch. Nationales du Québec (Trois-Rivières, Québec); the Centre d’Arch. de Montréal holds the Robert Rumilly fonds (P303), which contains all the documentation assembled by the historian to write his brilliant biography, Le Frère Marie-Victorin et son temps (Montréal, 1949).

Marie-Victorin has been the subject of several other biographies, notably L. P. Audet, Le Frère Marie-Victorin, éducateur: ses idées pédagogiques (Québec, 1942); Pierre Couture, Marie-Victorin: le botaniste patriote (Montréal, 1996); Madeleine Lavallée, Marie-Victorin: un itinéraire exceptionnel (Saint-Lambert, Québec, 1983); and André Lefebvre, Marie-Victorin, le poète éducateur (Montréal, 1987). He has also inspired the creation of some films produced by the National Film Board of Canada (Montreal): Marie-Victorin, directed by Clément Perron, produced by Victor Jobin and Fernand Dansereau in 1963; and Victorin, le naturaliste and La passion de Victorin, directed by Nicole Gravel and produced by Éric Michel in 1997 and 1998 respectively.

Worth mentioning among the works and articles that shed light on certain aspects of his career are: Luc Chartrand, “Les amours secrètes du frère Marie-Victorin,” L’Actualité (Montréal), 15 (1990), no.3: 29–34; Luc Chartrand et al., Histoire des sciences au Québec (Montréal, 1987); Pierre Dansereau, “Science in French Canada, II: scientific endeavor,” Scientific Monthly (Washington, D.C.), 59 (July–December 1944): 261–72; Dictionnaire des œuvres littéraires du Québec, sous la dir. de Maurice Lemire et al. (7v., 1980–87), 2; Yves Gingras, “Note critique: les combats du frère Marie-Victorin,” Rev. d’hist. de l’Amérique française (Montréal), 58 (2004–5): 87–101; F. E. Lloyd and Jules Brunel, “Frère Marie-Victorin,” Science (New York), new ser., 100 (July–December 1944): 487–88; Univ. de Montréal, Div. des arch., “Marie-Victorin: l’itinéraire d’un botaniste”: www.archiv.umontreal.ca/exposition/mv/expomv.htm (consulted 10 Feb. 2010); Nive Voisine, Les Frères des écoles chrétiennes au Canada (3v., Sainte-Foy [Québec], 1987–99), 2.

Revisions based on:

Frère Marie-Victorin [Conrad Kirouac], Lettres biologiques: recherches sur la sexualité humaine, Yves Gingras, édit. ([Montréal], 2018).

Cite This Article

Pierre Couture, “KIROUAC, CONRAD (baptized Joseph-Cyrille-Conrad), named Brother Marie-Victorin,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 17, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 10, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/kirouac_conrad_17E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/kirouac_conrad_17E.html |

| Author of Article: | Pierre Couture |

| Title of Article: | KIROUAC, CONRAD (baptized Joseph-Cyrille-Conrad), named Brother Marie-Victorin |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 17 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2011 |

| Year of revision: | 2020 |

| Access Date: | March 10, 2026 |