Source: Link

FASSIO, GEROME (often spelled Fascio, but he signed G. Fassio; some sources, without proof, put Giuseppe as his given name), painter, lithographer, and teacher of painting and drawing; b. in all likelihood in 1789 in Italy, probably in Rome; d. 1 Jan. 1851 in Bytown (Ottawa).

Gerome Fassio began doing portraits at Montreal late in the spring of 1834. At that time he was about 45 years old and had a son, Eugenio, who had been born in 1825 or 1826. Claiming that he had recently arrived from Italy, in the advertisements he placed in newspapers Fassio made much of the professional experience he had acquired in Europe and New York. In that city, where he had practised his art for at least a year on Broadway, he painted the portrait of a well-to-do citizen of Trois-Rivières, believed to have been Moses Hart. When Fassio came to Montreal he got in touch with Hart, and after spending some time there painting miniatures he went to Trois-Rivières, where he was working in 1835. Some sources suggest that he was then living with Hart; if so, it could not have been for long, since Fassio went to Quebec in August.

The visit to Quebec, like all Fassio’s activity in the Canadas, was characteristic of itinerant portraitists of that era in America. To attract the curious, he exhibited “a collection of choice pieces of the Italian School.” His work was launched with the backing of anonymous eulogies in Le Canadien concerning both the painter’s character and his art: “When people from abroad, instead of bringing us their vices, their woes, and their afflictions, dispense among us the benefits of science, the arts, and industry, and the amenities and gracious living that accompany them, they have a right to our full consideration.” The admirer continued on the subject of Fassio’s work: “What subtlety of colour, what deft shading! what faultless draftsmanship!” The writer in Le Canadien let it be known that Fassio was ready to spend the winter at Quebec “if he receives encouragement,” apparently at that time a virtual certainty. Towards the end of 1835, acknowledging the “encouragement he is receiving,” Fassio proposed to give “courses in painting in miniature and drawing” to young ladies and gentlemen. In the spring, however, he announced he was leaving at the end of May, and he reappeared in Montreal in August 1836. Hoping to deserve the “eminent encouragement that he so liberally enjoyed during his first stay,” he followed the formula that had been successful at Quebec and held separate classes for young ladies and for young gentlemen. But the town of Montreal was not destined to become the painter’s chosen ground, perhaps because of competition from other miniaturists. At Quebec Fassio could count on the support of the press and on undisputed professional pre-eminence .

Fassio was back at Quebec some time before the summer of 1838, when he left his lodgings on Rue Saint-Jean to move into the residence of the chief justice, Jonathan Sewell*. He received clients there, but no longer advertised painting and drawing lessons. To earn money with his brush, Fassio in 1839 executed and exhibited at Joseph Légaré’s picture-gallery an ambitious work on the theme of Great Britain and Canada; a sympathetic reporter described it as a “superb allegorical picture in miniature, on a large scale.” Lots were to be drawn for it, with tickets on sale at the painter’s house. The experiment cannot have proved successful, for Fassio never repeated it. The picture’s fate is unknown.

Fassio was drawing-master at the Petit Séminaire de Québec for the academic year 1839–40. Nothing is known of his activities during 1841, but he probably remained at Quebec. In May of the following year, while he was living on Rue Sainte-Hélène (Rue McMahon), he announced he was opening a new school of “classical drawing” that respected “the rules of art, and the practices of the great schools of Italy.” His fame attracted Michel Bibaud to Quebec in October; Bibaud, however, did not have enough time to meet the painter of the miniature portraits he had admired in Montreal.

In the autumn of 1843 Fassio tried his hand at lithography, putting his name to a portrait of Pope Gregory XVI which was dedicated with permission to the bishop of Quebec, Joseph Signay*. One critic noted “distinct progress in the country’s lithography,” while regretting that Fassio had “failed to give to Gregory XVI’s face the expression of kindliness and quiet contentment that . . . all the [other] likenesses of him convey.” Numerous copies of the lithograph must have been sold, for it continued to be advertised in Le Castor, which printed it, until about the beginning of March 1844, when the paper’s presses were destroyed by fire. This reverse must have been the more trying for Fassio because on 21 December he had been “stripped of all he possessed” when his house on Rue de la Fabrique burned down. At the end of February, recalling this calamity, he protested that he had “lost everything but [his] life.” The public does not seem to have been moved by the painter’s predicament. In addition, facing a new rival, the daguerreotype, Fassio was forced to cut his prices almost in half.

When Le Castor obtained a new press, Fassio hastened to turn it to good account; in June 1844 he produced a new lithographed portrait, of Louis-Joseph Papineau*, this one also printed by Le Castor. The paper’s editor, Napoléon Aubin*, himself an artist, was apparently encouraged by the success of these portraits, and published a prospectus in August announcing a “Galerie des illustrations canadienne,” to be sold by subscription. This was to be a collection of lithographed portraits “of a size convenient for framing or keeping in a notebook,” each accompanied by “a printed biographical notice.” Fassio’s portrait of Bishop François de Laval* was the first to appear. It was followed by ones of Joseph-François Perrault*, Bishop Charles-Auguste-Marie-Joseph de Forbin-Janson*, and Robert Baldwin; of these, Aubin did the first but it is not known which of them did the other two. Aubin abandoned the project towards the end of the year, no doubt because of a lack of subscribers.

After his son Eugenio had signed on as a sailor in training in July 1843, Fassio may have contemplated returning to his native land. He left Quebec early in 1845 but returned at the end of the summer. He recommenced teaching and painting, the latter at the same reduced prices, so that his art might be within everyone’s reach. None the less, Fassio seems to have maintained the quality of his portraits, witness the claim made in an article written in February 1846: “If his talent had not already brought him so far [along the road] to perfection, truly we would say he had made new conquests.”

Towards the end of 1847 Fassio made plans to return to Italy. His son was to have completed his apprenticeship in July of that year and to have become a navigator or pilot. Fassio now offered his clients the opportunity to avail themselves of his talents “for the last time” before his departure, which was arranged for the spring. He set his price at “four piastres” a portrait, but in February 1848 he lowered it to three, a sum that hardly seems remunerative in light of the ten days he required to complete a miniature portrait of Jean-Baptiste Godin. The painter’s plan to leave was frustrated, as he observed in October, “by unfortunate circumstances.” It may plausibly be assumed that he was referring to the political situation in Italy rather than to the cholera epidemic then raging in Lower Canada. He again took up residence at Quebec and planned to teach “the drawing of flowers and other elements of the same art” to adults.

Fassio left for Italy late in June 1849. Unfortunately the situation there was too precarious for him to consider a lengthy stay. Consequently, in October 1850, after an absence of less than 16 months, Fassio was back again at Quebec, some two months before his death. By a strange coincidence the issue of the paper carrying news of his return also announced the establishment at Quebec of “a new Canadian daguerreotype undertaking,” that of L.-A. Lemire, which seems to have been the first firm concerned solely with this art to be located at Quebec. Having exhausted his prospects in the two cut-rate campaigns he had launched before departing for Italy, the miniaturist was forced to settle elsewhere.

He chose Bytown, where he advertised for the first time at the end of November, describing himself as an Italian artist straight from Rome. He again adopted the formula he had developed over the years, which included painting lessons for small groups of young people and for adults on an individual basis. According to him, “a good education can never be complete without possessing a knowledge of this art.” To attract pupils Fassio noted that he had “taught with much success in different courts in Europe.” While the notice was still running, Fassio died of a severe illness on the morning of 1 Jan. 1851.

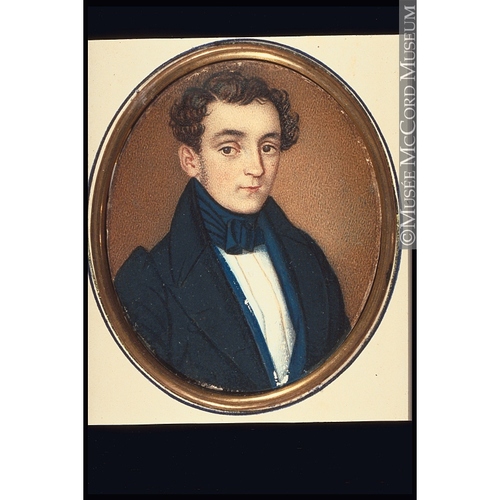

Fassio was a miniaturist in the true sense of the word, for the full precision of his brushwork can only be appreciated with a magnifying glass. He was also an excellent colourist, unrivalled in the province during his lifetime. His landscape Genève vu des Paquis reveals the measure of his two talents. The pigment is applied in minute dots in a well-ordered composition that is not unlike the work of Georges Seurat. But this static style gives the figures in his portraits a rigid air, so that they lose in vivacity what the work gains in style. Herein lies the painter’s weakness. As a European portraitist, Fassio was primarily concerned with the aesthetic requirements of his painting, however tiny it might be. In his miniatures on ivory he created the likeness of his subject, but the line is refined as if the image, instead of being painted, is engraved. There is a lack of expression in the faces, a flaw rightly identified by contemporary critics in the portrait of Gregory XVI.

The available sources imply that Fassio was a prolific artist. How many portraits in miniature he executed during his years in the Canadas and who posed for him are questions that cannot be answered precisely, but given the considerable esteem he enjoyed it may be conjectured that he often painted the portraits of prominent people, as he intimated at the end of his life. That the impecunious artist finally had to open his studio to humble folk suggests that his portraits could provide an interesting testimony to the ordinary life of his time.

[The author wishes to thank John R. Porter for having located Eugenio Fassio’s apprenticeship contract (ANQ-Q, CN1-49, 21 juill. 1843). d.k.]

A number of Gerome Fassio’s paintings are held at the BVM, the Musée du Québec (Québec), the Musée du Séminaire de Chicoutimi (Chicoutimi, Qué.), and at the National Gallery of Canada (Ottawa).

ASQ, mss, 433: 215–17. MAC-CD, Fonds Morisset, 2, F249/G537.5. L’Ami de la religion et de la patrie (Québec), 6 oct. 1848–25 juin 1849. Le Canadien, 31 août, 11, 14 sept., 14 déc. 1835; 8 janv., 2 mai 1836; 20 juill., 31 août, 5 sept. 1838; 15 nov. 1839; 9 mai 1842; 4 sept., 22 déc. 1843; 8 janv. 1844; 30 oct. 1848; 14 oct. 1850. Le Castor (Québec), 7 nov. 1843–25 nov. 1844. Le Journal de Québec, 7 sept. 1843; 29 févr. 1844; 6 janv., 7, 13 févr., 6 déc. 1845; 7 févr. 1846; 4 déc. 1847. Mélanges religieux, 15 sept. 1843. La Minerve, 19, 23 juin, 7 juill. 1834; 29 août 1836. Packet, 30 Nov. 1850–4 Jan. 1851. Quebec Mercury, 18 Aug. 1835; 30 April, 2 May 1836; 2, 11 Jan. 1844; 30 Sept. 1845. Gérard Morisset, “Giuseppe Fascio le miniaturiste,” La Patrie, 9 avril 1950: 26, 38.

Cite This Article

David Karel, “FASSIO (Fascio), GEROME (Giusepee),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 8, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 12, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/fassio_gerome_8E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/fassio_gerome_8E.html |

| Author of Article: | David Karel |

| Title of Article: | FASSIO (Fascio), GEROME (Giusepee) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 8 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1985 |

| Year of revision: | 1985 |

| Access Date: | March 12, 2026 |