Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

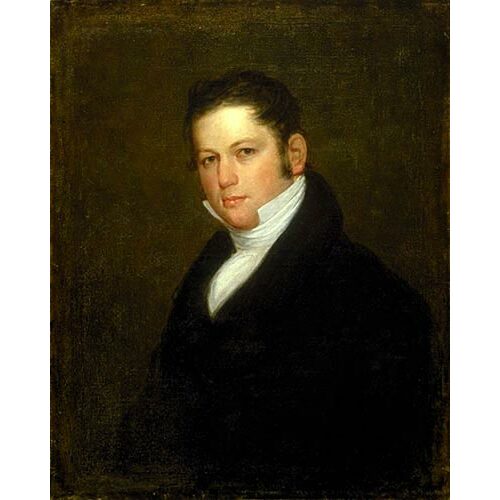

LÉGARÉ, JOSEPH, painter, glazier, landowner, seigneur, art gallery owner, politician, and justice of the peace; b. 10 March 1795 at Quebec, son of Joseph Légaré and Louise Routier; m. there 21 April 1818 Geneviève Damien, and they had 12 children, 7 of whom died in infancy; d. there 21 June 1855.

Joseph Légaré was the eldest of a family of six. His father initially worked as a shoemaker but by 1815 he had become a fairly prosperous merchant. In the autumn of 1810 young Légaré entered the first year at the Petit Séminaire de Québec. He was an indifferent student and probably terminated his studies in July 1811. Less than a year later, on 19 May 1812, he signed an apprenticeship contract with Moses Pierce, a painter and glazier who painted carriages, signs, and apartments, did gilding, and occasionally restored pictures. Légaré subsequently became a master painter and glazier, and in this capacity on 24 June 1817 he hired an apprentice, Henry Dolsealwhite.

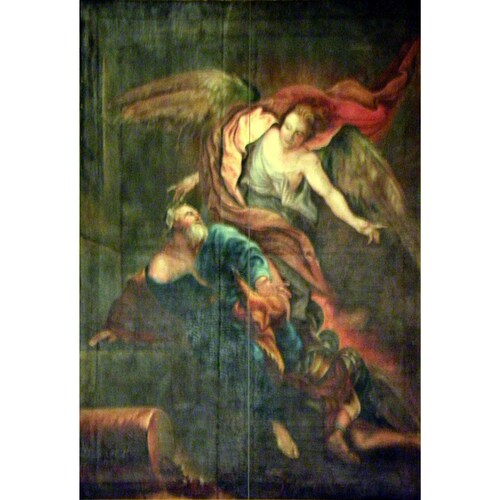

The arrival at Quebec that year of the canvases purchased by Abbé Philippe-Jean-Louis Desjardins* in France seems to have had a decisive influence on Légaré’s career. There is an outside chance that Légaré helped restore some of them. In 1819 he hired Antoine Plamondon* as an apprentice. By then Légaré was beginning to execute large copies of religious pictures, some of which came from the Desjardins collection. His earliest known works date from 1820.

The claim made by some historians that Légaré went to Europe to study painting is unfounded. Contemporary documents that broach the matter all describe Légaré as a self-taught painter, and stress that he never set foot on the Continent. Furthermore, towards the end of his life the artist confided to collector Edward Taylor Fletcher that soon after his marriage he had refused the governor’s offer to send him to Italy to improve his skills.

During the early years of his artistic career, Légaré did a great many copies of European religious canvases or engravings. This activity was a means of meeting the needs of parishes and religious communities, and at the same time enabled him to develop his gifts since it provided an opportunity to refine his pictorial techniques. Consequently it is not surprising that Légaré always retained an interest in painting copies of religious or secular works. In doing reproductions of the portraits of British monarchs George III, George IV, and Victoria, he also managed to make himself better known and to acquire more clients.

In 1828 Légaré was awarded a medal by the Société pour l’Encouragement des Sciences et des Arts en Canada, founded in Quebec, for his painting Le massacre des Hurons par les Iroquois. Despite obvious weaknesses, the canvas shows Légaré’s clear determination to diversify his production and explore new avenues. He helped decorate the new Théâtre Royal at Quebec in 1832. A year later his career took a decisive turn: in addition to designing the first seal of the city of Quebec and the logotype of Le Canadien, Légaré was for the first time described as a “history painter.”

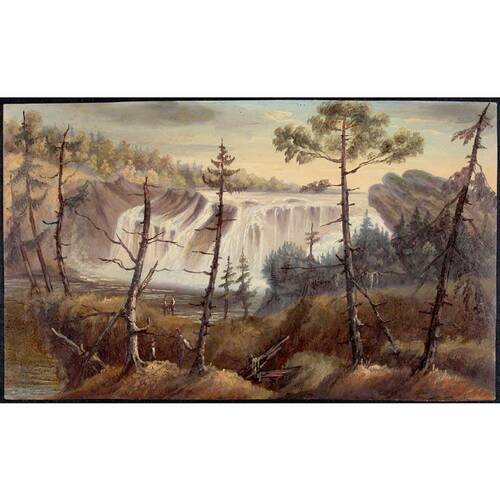

From then on Légaré sought to turn to account even the most minor of his talents, and his production became increasingly varied. He took an interest in everything, as accounts of his exhibitions in Montreal and Quebec between 1842 and 1848 demonstrate. For example, in August 1842 the editor of Montreal’s L’Aurore des Canadas could not contain his enthusiasm for “all the suppleness, all the diversity of talent and all the genius of the painter, who does as well in charmingly picturesque, or sylvan scenes as in solemn, pompous, or awe-inspiring ones,” adding that “all types of painting appear to suit and be familiar to his palette.”

At the outset of his artistic career Légaré had managed to purchase some 30 works from the Desjardins collection, and from this nucleus he developed a personal collection which by 1852 included 162 canvases. He took advantage of every opportunity to increase it, and in particular made several purchases from two Quebec merchants, John Christopher Reiffenstein* and Giovanni Domenico Balzaretti. Légaré began exhibiting his collection late in the 1820s, showing his work at the Union Hotel in premises lent by the government to the Literary and Historical Society of Quebec. In 1831, when the society received a royal charter, he was one of its most active members. Two years later he was appointed chairman of the arts class, and also was highly praised by the Reverend Daniel Wilkie during a lecture. Having had a new dwelling built on Rue Sainte-Angèle in 1833, he finally had enough room to house his entire collection of pictures and engravings. That year he invited the public to visit his gallery, the first in Lower Canada, a gesture that earned him the congratulations of the governor, Lord Aylmer [Whitworth-Aylmer*], and commendations from the newspapers. Légaré used all three storeys of his house for the collection, which was growing fast and already comprised some hundred pictures. His first gallery had to be closed in April 1835.

Three years later Légaré and lawyer Thomas Amiot opened the Galerie de Peinture de Québec in the building that Amiot had just built on the Place du Marché in Upper Town. Much was made at the time of its importance for artists eager to develop their skills. In 1838 as well, concerts were given in this “temple of fine arts,” as it was called, and a school of drawing and painting was directed by Henry Daniel Thielcke. The gallery also exhibited “landscape views” and, the following year, a portrait of Queen Victoria by the American painter Thomas Sully and a painting by Gerome Fassio. The arrangement between Légaré and Amiot dated back to 1836, when Légaré sold Amiot half of his collection which then included 134 pictures. In October 1838 Amiot came to an agreement with Légaré that he himself would go to Europe to sell part of their common collection. It is known that he found a purchaser for at least four pictures. Afterwards Amiot ran into serious financial difficulties and, because he was in Légaré’s debt, in March 1840 he handed back to him the pictures still in his possession. The Galerie de Peinture de Québec probably closed that year, after having almost been destroyed by fire.

In 1841 Légaré lent his support to a plan for an institute to bring together all the learned societies of Quebec. This project had been put forward by Nicolas-Marie-Alexandre Vattemare*, an enthusiast for cultural exchanges. Although in the end the institute, with its projected museum of art and academy of drawing and painting, was not established, it seems that Vattemare’s ideas had some influence on a plan for a national gallery developed in 1845. Eager to make use of a number of empty government buildings, Légaré and ten of his fellow citizens – among them Archibald Campbell*, Napoléon Aubin*, Daniel Wilkie, and Jean-Baptiste-Édouard Bacquet – suggested to the municipal authorities that such an establishment be set up at Quebec to foster interest in the fine arts in Lower Canada and to enable young people to study them. Since nothing came of this request, three years later Légaré temporarily exhibited some of his collection in the hall of the Parliament Building at Quebec. A letter in Le Canadien then blamed the government for failing to supply a suitable room, one large enough to house Légaré’s whole collection. Tired of the situation, in 1851 Légaré had a spacious vaulted gallery fitted out on the top floor of his new house at the corner of Rue Sainte-Angèle and Rue Sainte-Hélène (McMahon). The following year he published a catalogue of his collection and made admission to the gallery free. In September he received a visit from Lord Elgin [Bruce*], who expressed great satisfaction. According to Fletcher, this gallery was a favourite meeting place for Quebec artists and painting enthusiasts.

Since Légaré had never been. to Europe, he had to build his collection as best he knew how, drawing solely upon pictures that reached Quebec at this period. When these limitations are taken into account, the high quality of several works in his collection shows that he possessed remarkable flair. He was often consulted as an expert, for instance in 1853 when an inventory of Judge Bacquet’s large collection was taken. This included 17 pictures jointly owned by Bacquet and Légaré, as well as 70 pictures and 12 engravings which were chiefly landscapes, seascapes, and still lifes. Towards the end of his career Légaré served on selection committees for industrial exhibitions that took place at Quebec. In 1854 he was even a member of the provincial committee set up in anticipation of the universal exposition to be held in Paris the following year.

It would seem that Légaré’s many initiatives to promote the fine arts and foster interest in them did not produce all the results expected. In fact the only encouragement for his ventures came from some of the local élite. This limited success was due in large measure to the social and economic context of the period, and in some degree to the lack of tangible support from the government. Légaré was essentially a precursor whose initiatives went beyond the cultural needs of the society of his day. In this regard, there is keen insight in the observation that François-Xavier Garneau* made about Légaré the year he died: “The profound love he had for painting, one of the fine arts still so little known and so little appreciated in this land, where every thinking being is absorbed with material needs, made me regard him with sentiments of deep respect.”

As an artist Légaré himself painted some 250 works, including about 100 religious pictures, a limited number of portraits, mostly of his own circle, several landscapes, episodes of contemporary life, some remarkable history paintings, as well as genre scenes, still lifes, allegories, and utilitarian commissions. His artistic production therefore presents a clear contrast to that of his most prolific contemporaries, such as Jean-Baptiste Roy-Audy*, Antoine Plamondon, and Théophile Hamel*, all artists who gave greater attention to portraits and religious pictures. By its variety and boldness, his work was often ahead of what clients of the period wanted. Légaré was able to paint the subjects he chose without always having to think of a future sale, but it was only because he had a degree of material comfort based on his real estate holdings. He had two residences in succession on Rue Sainte-Angèle, and purchased three income-producing houses on the same street, plus a fourth on Rue Saint-Jean. He was also seigneur of part of the fief of Saint-François from 1827 to 1841.

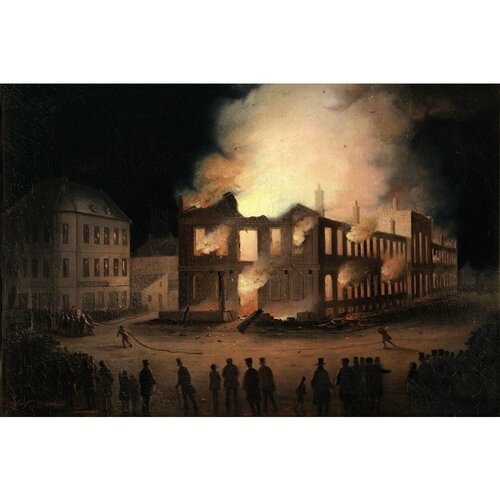

Landscape painting was one of the areas in which Légaré proved most innovative. The first landscape artist of French Canadian origin, he inherited from English topographical painters a distinct liking for waterfalls, rivers, forests, country houses, certain cityscapes, and, in general, picturesque views. It is known that his clientele of foreign residents, which included British officers garrisoned at Quebec, greatly appreciated this aspect of his work. Légaré also took an interest in the events of his day. Some of his paintings owe their origin to his social and political concerns. Examples include the drawing of the first seal of the city of Quebec, the logotype of Le Canadien, the banners he made for the Societé Saint-Jean-Baptiste of Quebec, and the paintings inspired by the cholera epidemic of 1832, the rock-fall at Cap Diamant in 1841, and the fires in the Saint-Roch and Saint-Jean wards in 1845. Other allegorical paintings, such as the Paysage au monument à Wolfe and the Scène d’élections à Château-Richer, have a more marked political connotation. A nationalist sensitive to the greatness of the past, Légaré interpreted in pictures several eloquent pages from the history of New France. Among his most remarkable history paintings are Premier monastère des ursulines de Québec, Souvenirs des jésuites de la Nouvelle-France, Le martyre des pères Brébeuf et Lalemant, and La bataille de Sainte-Foy. Légaré also painted a series of canvases depicting the customs of the Indians and portraying alternatively the concepts of the “noble savage” and the “barbaric savage.” In these the artist perfectly mirrors the dilemma of his contemporaries in their thinking about the Indians.

Légaré did not hesitate to confront the social and political problems that marked his period. As a citizen of Quebec and as a nationalist, he became increasingly involved in public matters. His particular interest in his city and fellow citizens apparently began with the terrible cholera epidemic that struck Quebec in 1832. At that time he was a member of the Quebec Board of Health and of a relief committee to help afflicted and needy families. He was elected to the municipal council in 1833, and represented the Palais Ward until 1836. Appointed to the grand jury in 1835, he was among those suggesting that improvements be made to a penitentiary system judged inadequate. A year later, when municipal administration once again became the responsibility of justices of the peace, Légaré discharged the duties of this office from 22 August until he was dismissed on 8 Nov. 1837.

In 1842 he helped found the Societé Saint-Jean-Baptiste of Quebec, and until 1847 he was vice-president of the first of its sections within the city. After that he maintained close ties with the association as a member of its management committee. Taken up with questions of education, he became an advocate of schools for children and evening classes for adults, and also encouraged the establishment of the Christian Brothers and the creation of public libraries. He was a member of the Quebec Education Society from 1841 to 1849 and supported the mechanics’ institute. Légaré in 1844 successfully directed a campaign for a fund to aid his friend Napoléon Aubin, the owner of Le Castor and Le Fantasque, whose printing works had burned down. Aubin’s workshop was again destroyed by the fire in Saint-Jean Ward in June 1845, a month after the fire in Saint-Roch Ward. Légaré took an active part in numerous meetings of committees to assist the victims of the fires. In addition he participated in various collections for humanitarian purposes in 1846, 1847, and 1852.

Légaré was a justice of the peace almost continuously from 1843 to 1852, a member of the board of health from 1847 to 1849, a churchwarden of the parish of Notre-Dame from 1846 to 1848, and a member of the grand jury in 1843 and 1846. In 1849 he again recommended that the penitentiary system be improved, and he chaired a committee which sought changes in the charter of the city of Quebec. By 1845 he was fully aware of the commercial advantages of railways, and he eagerly promoted them in 1849 and 1852.

A respected citizen, Légaré was quick to take a stand on questions concerning the moral and material progress of his country. Despite the disappointments he encountered in this connection, he remained faithful to his principles and convictions. From 1827 he was an unwavering admirer of Louis-Joseph Papineau*. In 1834 he was among those who solicited signatures for a petition in favour of the 92 Resolutions, which outlined the main grievances and demands of the House of Assembly. Two years later he headed a delegation to Papineau in support of the action he and the Patriote members still loyal to him in the house had taken. He participated in 1837 in all the activities of the Quebec Patriotes, and became one of the directors of the reform paper Le Libéral, which was opposed to Étienne Parent*’s moderate Le Canadien. As a member of the Comité Permanent de Québec, Légaré was arrested and jailed on 13 November. He was set free on bail five days later to await a trial, which, in the event, never took place. He subsequently opposed the union of the Canadas, and supported the anti-unionists in several elections. He gave his backing to his friend Pierre-Joseph-Olivier Chauveau*, who ran successfully as a reform candidate in 1844.

Three years later Légaré became more involved with the political scene in Lower Canada. In 1847 he was elected deputy chairman of the Comité Constitutionnel de la Réforme et du Progrès, a political association chaired by René-Édouard Caron*. The following year one of the assembly members for the city of Quebec, Thomas Cushing Aylwin*, was appointed to the bench, and an election to fill the vacant seat was announced. At that time the ranks of politicians of liberal bent were divided. Two candidates stood, Légaré and the merchant François-Xavier Méthot. Légaré, who supported the reformers in power but did not deny his sympathy for Papineau, won the majority of the French Canadian votes but was nevertheless beaten by Méthot, who had the backing of the Quebec Mercury and the tories. In 1850 Légaré ran again in a by-election, this time on the ticket of the Rouges who favoured annexation of the province to the United States. After many rebuffs, he was defeated by Jean Chabot, the new commissioner of public works. During his two bids for election, Légaré had been subjected to attack by Joseph-Édouard Cauchon*, the member for Montmorency and owner of Le Journal de Québec. Consequently he supported Cauchon’s opponent in the 1851 general elections, although the effort was in vain.

In the 1854 elections Joseph Légaré backed the reform candidates in the ridings of the city and county of Quebec, who were all elected. One of them, his friend Chauveau, entered the government, and it was on his recommendation that Légaré was appointed to the Legislative Council on 8 Feb. 1855, only a few months before his death.

[At Joseph Légaré’s death a large part of his work remained with his widow, and then in 1874 went almost in its entirety to the Université Laval in Quebec. That institution, which came under the Séminaire de Québec, acquired at the same time his important collection of European canvasses and engravings.

This biography summarizes the author’s doctoral thesis, “Un peintre et collectionneur québécois engagé dans son milieu: Joseph Légaré (1795–1855)” (Univ. de Montréal, 1981), which is to be published and which is a companion piece to the author’s descriptive catalogue of all Légaré’s works, put out by the National Gallery of Canada, The works of Joseph Légaré, 1795–1855 (Ottawa, 1978). The two works, the first to deal comprehensively with Légaré, shed a wholly new light on the subject. The more important items in the 70-page bibliography accompanying the thesis are listed here. j.r.p.]

ANQ-MBF, CN1-11, 2 mai 1839. ANQ-Q, CE1-1, 11 mars 1795, 21 avril 1818, 21 juin 1855; CN1-18, 3 avril 1843, 17 juill. 1852, 24 janv. 1853; CN1-62, 18, 26 avril 1853; CN1-80, 30 août 1851; CN1-116, 4, 31 déc. 1837; 29 nov. 1847; CN1-178, 19 mai 1812, 26 mars 1814, 14 sept. 1815, 7 avril 1837, 17 janv. 1838, 2 juill. 1841; CN1-208, 11 mai, 4 juin, 7 août 1830; 9 mars 1832; CN1-212, 1er mars, 8 juill. 1819; 20 juin, 27 juill., 12 nov. 1830; 29 juill. 1834; 8 oct. 1836; 7 déc. 1841; CN1-213, 8 janv., 3 avril, 27 juill. 1846; 13 déc. 1849; CN1-219, 31 mai 1843, 9 juin 1848, 14 août 1850, 15 août 1853; CN1-255, 25 juill. 1836; 9 mai, 19 oct. 1838; 11 janv. 1839; 23 mars 1840; 25 janv. 1848; CN1-260, 9 févr. 1842, 27 août 1852, 28 juill. 1854; CN1-261, 21 déc. 1827, 1er mars 1833; 13 avril 1835; 5, 6 août 1851; CN1-285, 12 mai 1834; CN4-9, 24 juin 1817; P-75. ASQ, C 28: 145; C 31: 355; C 66: 833; Fonds Viger–Verreau, carton 61, liasse 7, nos.4–6, 6, 13 déc. 1839, 22 févr. 1840; carton 62, no.227, 23 nov. 1839; Journal du séminaire, II: 563–64; Polygraphie, XXXI, no.19A; Séminaire, 12, no.41; 103, no.54. AVQ, II, 1, a. MAC-CD, Fonds Morisset. Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, J. W. H. Watts coll., 24 Dec. 1889. La Bibliothèque canadienne (Montréal), 6 (1827–28); 9 (1829). Can., Prov. of, Legislative Council, Journals, 1854–55: 273, 500. L’Abeille, janvier 1850. L’Ami de la religion et de la patrie (Québec), 1848–50. L’Aurore des Canadas (Montréal), 18 oct. 1839; 30 août, 24 déc. 1842; 26 juin 1845. Le Canadien, 25 déc. 1818; 13 mars 1822; 3 sept. 1823; 1833–55. Le Castor (Québec), 1843–45. Le Fantasque (Québec), 14 juill. 1838; 15 mars 1841; 30 juin, 1er sept., 13, 17, 21, 24 déc. 1842; 22 avril, 3, 20 juill. 1843; 17 juin, 8, 15 juill. 1848. La Gazette patriotique (Québec), 9 août 1823. Le Journal de Québec, 18 sept. 1847; 1848; 1850; 15 juin, 28 sept. 1852; 7 juin 1853; 21 juin 1855. Le Libéral (Québec), 1837. Mélanges religieux, 2 nov. 1849. La Minerve, 2 oct. 1828; 9 avril 1829; 1er nov., 9 déc. 1830; 18 avril, 5 sept. 1836; 1er juin, 24 sept. 1837; 15 mai, 7 sept. 1848; 25 juin 1849. Le Populaire (Montréal), 14, 16 juin, 17 nov. 1837; 17 août 1838. Quebec Gazette, 8, 15 April, 30 Dec. 1813; 22 Dec. 1814; 3, 24 Aug., 19 Oct. 1815; 9 April 1818; 22 April 1819; 5 June 1820; 16 April 1821; 29 May 1828; 23 Nov., 10 Dec. 1829; 14 Jan. 1830; 27 Nov., 13 Dec. 1833; 10 Nov. 1837; 27 June 1838; 30 May 1845. Quebec Mercury, 16 Sept. 1817; 1829–55. Quebec Spectator, and Commercial Advertiser, 6 Oct. 1848. F.-M. Bibaud, Le panthéon canadien (A. et V. Bibaud; 1891). Joseph Bouchette, The British dominions in North America; or a topographical and statistical description of the provinces of Lower and Upper Canada . . . (2v., London, 1832), 1: 252. Canada, an encyclopædia of the country: the Canadian dominion considered in its historic relations, its natural resources, its material progress, and its national development, ed. J. C. Hopkins (6v. and index, Toronto, 1898–1900), 4: 355. Catalogue of the Quebec gallery of paintings, engravings, etc., the property of Jos. Legaré, St. Angele Street, corner of St. Helen Street, comp. E.-R. Fréchette (Quebec, 1852). P.-V. Charland, “Notre-Dame de Québec: le nécrologe de la crypte ou les inhumations dans cette église depuis 1652,” BRH, 20 (1914): 313. The encyclopedia of Canada, ed. W. S. Wallace (6v., Toronto, [1948]), 4: 59. Fauteux, Patriotes, 33, 295–96. Harper, Early painters and engravers, 194. P.-G. Roy, Fils de Québec, 3: 67–70. Turcotte, Le Conseil législatif, 21, 155–56. Georges Bellerive, Artistes-peintres canadiens-français: les anciens (2 sér., Québec, 1925–26), 1: 9–24. H.-J.-J.-B. Chouinard, Fête nationale des Canadiens français célébrée à Québec en 1880: histoire, discours, rapports . . . (4v., Québec, 1881–1903), 1: 55, 58–59, 73, 597. Chouinard et al., La ville de Québec, 3: 9, 15, 70–73. W. [G.] Colgate, Canadian art; its origin & development (Toronto, 1943; repr., 1967), 108–9. J. R. Harper, La peinture au Canada des origines à nos jours (Québec, 1966), 79–82. Barry Lord, The history of painting in Canada: toward a people’s art (Toronto, 1974), 48–54. N. M. MacTavish, The fine arts in Canada (Toronto, 1925), 8. Morisset, Coup d’œil sur les arts, 62; Peintres et tableaux (2v., Québec, 1936–37), 1; La peinture traditionnelle au Canada français (Ottawa, 1960), 94–101. Edmund Morris, Art in Canada: the early painters ([Toronto, 1911]). Painting in Canada, a selective historical survey (Albany, N.Y., 1946), 27. D. R. Reid, A concise history of Canadian painting (Toronto, 1973), 46–49. A. H. Robson, Canadian landscape painters (Toronto, 1932), 18–20. [J.-C. Taché], Le Canada et l’Exposition universelle de 1855 (Toronto, 1856), 8, 13. Claire Tremblay, “L’œuvre profane de Joseph Légaré” (mémoire de ma, univ. de Montréal, 1973). Hormidas Magnan, “Peintres et sculpteurs du terroir,” Le Terroir (Québec), 3 (1922–23): 347. Olivier Maurault, “Souvenirs canadiens; album de Jacques Viger,” Cahiers des Dix, 9 (1944): 98. Gérard Morisset, “Joseph Légaré, copiste,” Le Canada (Montréal), 12 sept. 1934: 2; 25 sept. 1934: 2; “Joseph Légaré, copiste à l’église de Bécancour,” 12 déc. 1935: 2; “Joseph Légaré, copiste à l’Hôpital Général de Québec,” 18 juin 1935: 2; “Joseph Légaré, copiste à Saint-Roch-des-Aulnaies,” 4 juill. 1935: 2; “Une belle peinture de Joseph Légaré,” 23 juill. 1934: 2. “Les peintures de Légaré sur Québec,” BRH, 32 (1926): 432. J. R. Porter, “L’apport de Joseph Légaré (1795–1855) dans le renouveau de la peinture québécoise,” Vie des Arts (Montréal), 23 (1978), no.92: 63–66; “L’architecture québécoise dans l’œuvre de Joseph Légaré,” Conseil des monuments et sites du Québec, Bull., 6 (mai 1978): 19–21; “Joseph Légaré, painter and citizen,” National Gallery of Canada, Journal (Ottawa), no.29 (September 1978); “La société québécoise et l’encouragement aux artistes de 1825 à 1850,” Journal of Canadian Art Hist. (Montreal), 4 (1977), no.1: 13–14; “Un projet de musée national à Québec à l’époque du peintre Joseph Légaré (1833–1853),” RHAF, 31 (1977–78): 75–82. Antoine Roy, “Les Patriotes de la région de Québec pendant la rébellion de 1837–1838,” Cahiers des Dix, 24 (1959): 247.

Cite This Article

John R. Porter, “LÉGARÉ, JOSEPH,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 8, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 19, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/legare_joseph_8E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/legare_joseph_8E.html |

| Author of Article: | John R. Porter |

| Title of Article: | LÉGARÉ, JOSEPH |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 8 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1985 |

| Year of revision: | 1985 |

| Access Date: | February 19, 2026 |