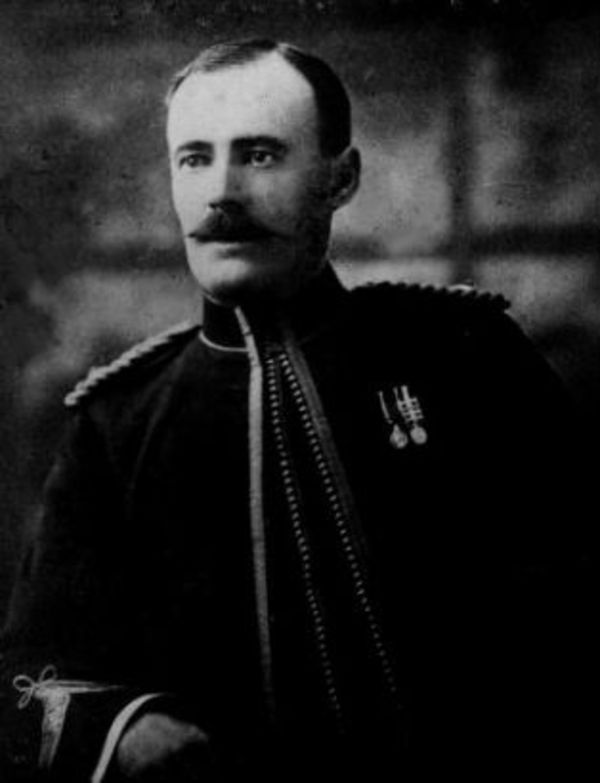

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

FITZGERALD, FRANCIS JOSEPH, RNWMP officer and soldier; b. 12 April 1869 in Halifax, second son of John Fitzgerald, a telegraph company employee, and Elizabeth Pickles; d. on or about 14 Feb. 1911 beside the Peel River south of Fort McPherson, N.W.T.

Little is known of Frank Fitzgerald’s early life. He served with the militia in Halifax before leaving his job there as a clerk in a store to enlist as a constable in the North-West Mounted Police on 19 Nov. 1888. Most of his next nine years were spent in the Maple Creek District (Sask.), where he found that the monotonous military routine of life at a police post failed to satisfy his adventurous spirit. During this period he did not distinguish himself in any way.

Fitzgerald’s opportunity for advancement came in 1897 when he was selected to join a small party under the command of Inspector John Douglas Moodie, whose task was to chart an overland route from Edmonton to the Yukon gold-fields via northern British Columbia and the Pelly River, a region largely unknown to whites. The party left Edmonton in September 1897. Travelling on horseback and by dog sled and canoe over almost insurmountable obstacles, it reached its objective, Fort Selkirk on the Yukon River, in October 1898, having covered about 1,000 miles. During this epic journey, Fitzgerald exemplified those qualities necessary for survival in the north. He was resourceful and tough, both physically and mentally, characteristics that would further his police career. Moodie praised Fitzgerald’s performance in his report to his superiors. As a result he was promoted corporal in 1899.

The following year Fitzgerald was given leave of absence, along with other members of the NWMP, to join the 1st Canadian Mounted Rifles, part of the force sent to fight in the South African War under the command of Lawrence William Herchmer. Once again his good service was brought to the attention of Commissioner Aylesworth Bowen Perry in Regina, and he was raised to sergeant after his return to Canada. He went to England in 1902 with the NWMP contingent for the coronation of Edward VII.

In the summer of 1903 Fitzgerald and a constable were sent to Herschel Island in the western Arctic to establish a police post following reports that the crews of the whaling ships that wintered there were demoralizing the native population. This isolated location was the most northerly station of the force (renamed the Royal North-West Mounted Police in 1904), and it was to be Fitzgerald’s base for six years, during which time he became a highly experienced northern traveller. With tact he put a stop to whisky trading and collected customs, thereby asserting Canadian sovereignty under difficult conditions and to the entire satisfaction of his superiors. His only links with the outside world were the whaling ships that visited occasionally, police whaleboats from Fort McPherson in the Mackenzie delta, and a police patrol by dog sled from that post. Relieved in the summer of 1909, he went to Regina, but in July 1910 he returned to Fort McPherson.

While at Herschel, Fitzgerald established a marital relationship according to native custom, as did many other white men in the north. From his union with Lena Oonalina, an Inuit woman, a daughter was born in the summer of 1909. Fitzgerald had wanted to have the association legitimized by the local Church of England missionary, Charles Edward Whittaker, but was dissuaded from doing so by the commanding officer of the Mackenzie River District, Arthur Murray Jarvis. Meanwhile, unaware of this situation, Fitzgerald’s superiors in Regina had secured his advancement to inspector on 1 Dec. 1909. It was a well-merited promotion, one based on outstanding service and not, as often was the case at the time, on patronage. However, in the opinion of white society, it was unacceptable for an officer of the RNWMP to have a liaison with a native woman, legitimate or otherwise. Had his superiors known of Fitzgerald’s situation, they would never have recommended his promotion. Once they found out, they most likely would have demanded his resignation. It was his death that would save him from almost certain disgrace and keep his secret from becoming widely known until several years later.

In late 1910 Fitzgerald was selected for the contingent to be sent to George V’s coronation. To get him out of the north in time, it was decided that he would head the annual patrol that winter from Fort McPherson to Dawson, a distance of some 470 miles. Given the competitive spirit within the police, Fitzgerald undoubtedly saw this trip as an opportunity to break the time record set by an earlier patrol. He therefore decided to lighten the load on his sleds by reducing food and equipment, confident that the quantities normally taken would not be needed.

On 21 Dec. 1910 Fitzgerald left Fort McPherson with constables George Francis Kinney and Richard O’Hara Taylor. They were accompanied by Samuel Carter, a former constable who was to act as guide. Carter, however, had only travelled the route in the opposite direction, four years before. From the outset, the patrol was slowed by heavy snow and temperatures as low as minus 62 degrees. Worst of all, Carter was unable to find the route across the Richardson Mountains. Nine days were wasted searching for it. With supplies dwindling, Fitzgerald reluctantly had to admit defeat and return to Fort McPherson. The patrol now faced a desperate struggle. As food ran out, they began eating their dogs. In the last entry in his diary, on 5 February, Fitzgerald recorded that five were left and the men were so weak they could travel only a short distance. Within a few days all four died, three from starvation and exposure and one, Taylor, by suicide. Their emaciated bodies were found in March a few miles from the safety of Fort McPherson, where they were buried.

Fitzgerald was rightly criticized for overconfidence, failing to take a native guide, reducing rations, and not turning back sooner when Carter was unable to find the trail. Time, however, has blurred these failings of the Lost Patrol, as it became known, and Fitzgerald and his men are largely remembered for their heroic struggle to survive. Following the tragedy, Commissioner Perry issued instructions for emergency caches of food to be left along the route from Dawson to Fort McPherson, and for all patrols by the police over routes unknown to them to be accompanied by experienced guides.

Francis Joseph Fitzgerald’s original diary and will are preserved in the Royal Canadian Mounted Police Museum, Regina; they are printed on pp.310–14 of “Reports and other papers relating to the McPherson–Dawson police patrol – winter 1910–11 . . . ,” in the report of the Royal North-West Mounted Police for 1911 (Can., Parl., Sessional papers, 1912, no.28, pt.v).

NA, RG 18, 3448, file 0-156. Regina Leader, April 1911. Can., Parl., Sessional papers, 1898–1911, reports of the (Royal) North-West Mounted Police, 1897–1910. W. R. Morrison, Showing the flag: the mounted police and Canadian sovereignty in the north, 1894–1925 (Vancouver, 1985). Dick North, The Lost Patrol (Anchorage, Alaska, 1978).

Cite This Article

S. W. Horrall, “FITZGERALD, FRANCIS JOSEPH,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 19, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/fitzgerald_francis_joseph_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/fitzgerald_francis_joseph_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | S. W. Horrall |

| Title of Article: | FITZGERALD, FRANCIS JOSEPH |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1998 |

| Year of revision: | 1998 |

| Access Date: | February 19, 2026 |