Source: Link

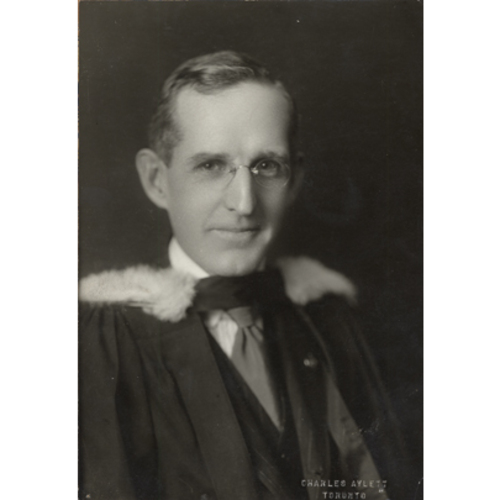

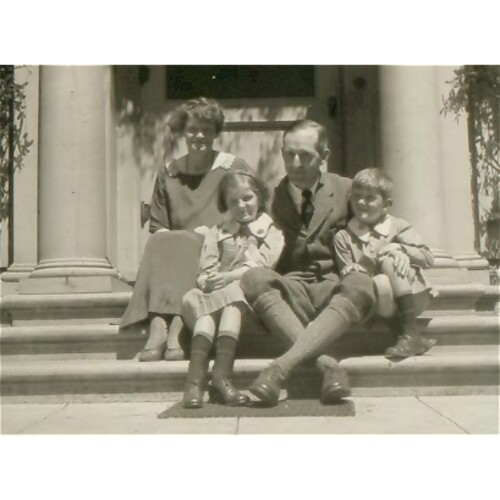

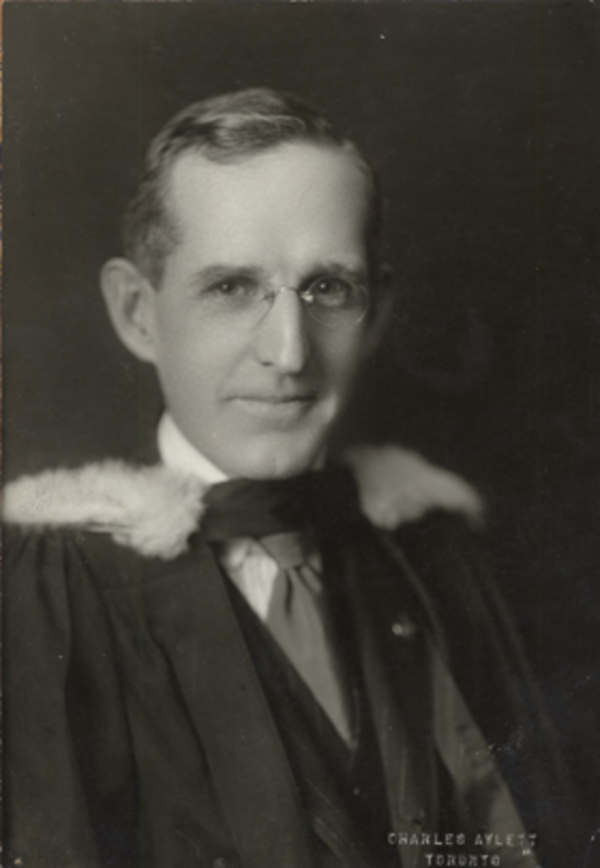

FitzGERALD, JOHN GERALD, pathologist, bacteriologist, public-health reformer and educator, and author; b. 9 Dec. 1882 in Drayton, Ont., eldest of the four children of William Fitzgerald, a pharmacist, and Alice Ann Woollatt; m. 9 April 1910 Edna Ella Mary Leonard in London, Ont., and they had a daughter and a son; d. 20 June 1940 in Toronto.

John Gerald FitzGerald’s paternal great-grandfather had emigrated to Upper Canada from Clones, County Monaghan (Republic of Ireland), in 1824. His mother was English born. Gerry, as the young boy was known, moved with his family from Drayton to nearby Harriston in 1891. While attending the local high school, he worked part-time as an apprentice in his father’s apothecary shop and cared for his invalid mother. Following his graduation in 1899, he entered the University of Toronto’s faculty of medicine; at age 16 he was the youngest in his class.

Perhaps inspired by his own family’s history of mental instability, FitzGerald was keen to discover the biological roots of insanity. He interned first at Donald Campbell Meyers’s private Neurological Hospital in Toronto and then at the state asylum for the insane in Buffalo, N.Y. There he came under the influence of the eminent psychiatrist Adolf Meyer, a co-founder of the mental-hygiene movement. At Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, Md, he was inspired by the leading figure in American public health, William Henry Welch, and at the Sheppard and Enoch Pratt Hospital, on the outskirts of the city, he made a lifelong friend of Clarence Byrnold Farrar*, later to become director of the Toronto Psychiatric Hospital.

In 1907 FitzGerald was appointed the first pathologist and clinical director of the Toronto Hospital for the Insane by its superintendent, Charles Kirk Clarke*, and a demonstrator in psychiatry at the University of Toronto. But his interests were now shifting. The following year he resigned from the asylum, and after research at the Harvard Medical School and the state hospital for the insane in Danvers, Mass., he returned to the University of Toronto in 1909 as a lecturer in bacteriology. A year later he married Edna May Leonard, as she was known, the granddaughter and heiress of iron founder Elijah Leonard*. The couple moved to Berkeley, Calif., in 1911 when he was made an associate professor at the university there.

Over an intense three-year period from 1910 to 1913, during which he sacrificed his summer vacations, FitzGerald deepened his training in pathology and bacteriology and broadened his links with leading international scientists. As a researcher at the Institut Pasteur du Brabant in Brussels, he got to know its founder, biologist Jules Bordet, and Élie Metchnikoff, the father of immunology, and in Paris he formed a lasting friendship with Émile Roux, Louis Pasteur’s principal collaborator. He also learned how to make Pasteur’s rabies treatment, diphtheria antitoxin, and smallpox vaccine. Sojourns at the University of Freiburg in Germany, the Lister Institute of Preventive Medicine in London, and New York City’s public-health department capped a decade of fast-paced specialist training following his mb.

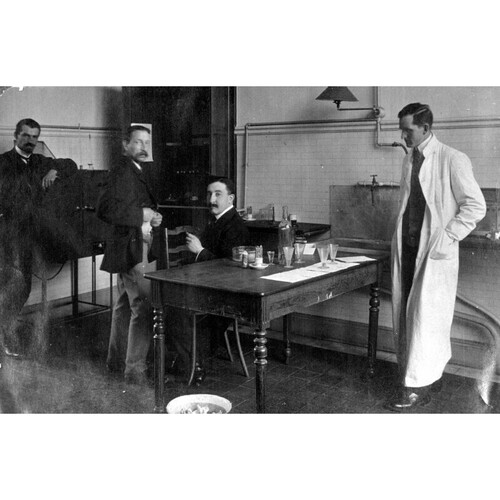

FitzGerald came back to Toronto in 1913. Appointed an associate professor in the new department of hygiene at the university, he was eager to realize his vision for reforming public health in Canada. In the absence of effective programs, thousands were dying each year from a variety of infectious diseases. Diphtheria alone was a leading killer of children under 14. Prohibitively expensive antitoxins, serums, and vaccines, imported from the United States, were available only to the wealthy. FitzGerald began by working in the Provincial Board of Health laboratory, producing the rabies treatment he had learned in Paris. Later the same year he approached the University of Toronto’s board of governors with a proposal to set up a laboratory in the department of hygiene where a range of high-quality preventive medicines could be manufactured at costs low enough to make them universally available – “within reach of everyone,” in the words of a contemporary.

But before he had received the university’s approval, the passionate, 30-year-old professor plunged ahead on his own. With money borrowed from his wife’s inheritance, he acquired some horses destined for the glue factory and housed them in a small stable he had built on Barton Avenue. There, after injecting the animals with toxin cultivated from the diphtheria bacillus, he used the antibodies produced in their blood to create Canada’s first antitoxin for the disease. FitzGerald’s forceful demonstration of the potential of his idea convinced the university to establish the Antitoxin Laboratory, which was launched on 1 May 1914 in the basement of the medical school. Following the outbreak of World War I only months later, an urgent need arose to immunize Canadian troops against tetanus. Impressed with FitzGerald’s drive and commitment, philanthropist Albert Edward Gooderham donated land, buildings, and funds to greatly expand the laboratory’s capacity. The Connaught Antitoxin Laboratories and University Farm, named after a recent governor general, the Duke of Connaught [Arthur*], was formally opened on 25 Oct. 1917 on 58 acres northwest of the city.

In February the previous year the Provincial Board of Health had begun distributing antitoxins, serums, and vaccines free of charge in Ontario, placing the province in the vanguard of public health in Canada. Other provinces would follow. As the facility pumped out preventive remedies for civilian and military use, FitzGerald, now a major, served first with the Canadian Army Medical Corps, providing soldiers with health services before they went overseas, and then in 1918 with the Royal Army Medical Corps, as commander of a mobile pathology laboratory on the Western Front. The following year he was appointed the first full-time professor of hygiene and preventive medicine at the University of Toronto, and in 1920 he became a member of the Dominion Council of Health, an advisory body attached to the newly established national Department of Health. He was now at the hub of a nascent reform movement in public health.

After Frederick Grant Banting* and Charles Herbert Best*, together with John James Rickard Macleod and James Bertram Collip*, discovered insulin in 1921–22, the Connaught Laboratories raced to meet the challenge of refining and producing the hormone. Impressed with this Canadian breakthrough in the treatment of diabetes and the advances being achieved in Toronto under the city’s medical officer of health, Charles John Colwell Orr Hastings, the New York–based Rockefeller Foundation donated a total of $1.25 million to set up the school of hygiene at the University of Toronto and endow new departments in epidemiology and physiological hygiene. The four-storey building, which opened on College Street on 9 June 1927, was designed to serve as the academic branch of the Connaught Laboratories. As its founding director, FitzGerald was now realizing his long-standing dream of uniting education, research, and the production of vaccines and serums under one roof. During the 1920s and 1930s this distinctive Canadian model of public service set a new international standard of excellence, leading to the systematic control or eradication of a spectrum of diseases that, in addition to diabetes, included rabies, diphtheria, typhoid fever, smallpox, tetanus, pneumonia, meningitis, pertussis (whooping cough), and scarlet fever. The Connaught’s successful development of a diphtheria toxoid in the 1920s helped advance FitzGerald’s career internationally and led to Toronto and Hamilton, Ont., being declared free of the disease by the time of his death in 1940, the first cities in the world to achieve this status. His textbook, An introduction to the practice of preventive medicine (St Louis, Mo., 1922; 2nd ed., 1926), written with several colleagues, was widely used throughout North America.

He had been a member of the Rockefeller Foundation’s international health board since 1923, and he served as a scientific director of its successor, the international health division, the first Canadian to be appointed. Concurrently, from 1930 to 1936 he was a member of the Health Committee of the League of Nations, a precursor of the World Health Organization. In 1932 he began a three-year term, later extended by a year, as dean of medicine at the University of Toronto, during which he overhauled the curriculum to place more emphasis on preventive measures such as nutrition, sanitation, mental health, and public education.

FitzGerald was involved in two international missions for the Rockefeller Foundation. The first, in 1934, surveyed health conditions in Ceylon (Sri Lanka), India, and Egypt, and the second, over 12 months in 1936–37, assessed undergraduate education in public health and preventive medicine in 26 countries in Europe and North America. The latter assignment, coming after decades of overwork, exacted a heavy toll. He had long suffered from episodes of depression, which he attempted to stave off by driving himself relentlessly. As a result, he experienced migraine headaches, a bleeding ulcer, and insomnia. In late 1938 he made a failed suicide attempt following a nervous collapse. The following May he was admitted to the Neuropsychiatric Institute of the Hartford Retreat in Connecticut, where he received 57 insulin-shock treatments, a controversial new therapy for depression. After returning to work in the spring of 1940, he had a relapse and died by his own hand at the Toronto General Hospital in June, at the age of 57.

John Gerald FitzGerald was a complex human being full of contradictions. C. B. Farrar remembered him as “calm, soft spoken, kindly, judicial and tolerant,” a lovable person with a concern for others and an ability to delegate responsibility. Another colleague praised his imagination and vision, which he said were combined with “gentleness, modesty, and charm of character.” But under the placid exterior was a forceful, sometimes-ruthless individual obsessed with reaching his goals. After his death his wife complained to a journalist that she had been “married to an idea, not a man.” Over a widely travelled career, he had conceived an overarching vision of public health that not only laid the foundations for provincial and federal programs across Canada but also influenced medical research and teaching on an international scale. As a result in large part of his foresight, within a single generation between the world wars, Canada leaped from colonial backwater to recognized world leader in preventive medicine. His honours included fellowships in the Royal Society of Canada (1920) and the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada (1931) and an lld from Queen’s University in Kingston, Ont. (1925). The FitzGerald Academy in undergraduate medical education was established at Toronto’s Wellesley and St Michael’s hospitals in 1994. FitzGerald was inducted into the Canadian Medical Hall of Fame ten years later.

In addition to the textbook mentioned in the biography, John Gerald FitzGerald is the author or co-author of nearly 90 articles, pamphlets, and scientific papers. He served as a co-editor of the Bull. of the Toronto Hospital for the Insane, later the Bull. of the Ontario Hospitals for the Insane (Toronto), in 1907–8. A bibliography of his published work (n.p., n.d.) is held by the Univ. of Toronto Libraries. What disturbs our blood: a son’s quest to redeem the past (Toronto, 2010), written by his grandson James FitzGerald, who had access to family records, provides background sources for FitzGerald’s life and career. A video describing his contribution to public health in Canada, prepared in connection with his induction into the Canadian Medical Hall of Fame, can be viewed at: http://www.cdnmedhall.org/inductees/dr-john-fitzgerald.

AO, RG 22-305, no.91642; RG 80-2-0-189, no.36744; RG 80-5-0-416, no.15506. UTARMS, B1999-0011/025(05); B2000-0005. “The antitoxin laboratory of the University of Toronto,” Canadian Medical Assoc., Journal (Toronto), 7 (1917): 255–60. Gordon Bates, “Lowering the cost of life-saving,” Maclean’s, 28 (1915), August: 14–16, 103–4. P. A. Bator, “‘Saving lives on the wholesale plan’: public health reform in the city of Toronto, 1900 to 1930” (phd thesis, Univ. of Toronto, 1979). P. A. Bator, with A. J. Rhodes, Within reach of everyone: a history of the University of Toronto School of Hygiene and the Connaught Laboratories (2v., Ottawa, 1990–95). Michael Bliss, The discovery of insulin (Toronto, 1982). R. D. Defries, The first forty years, 1914–1955: Connaught Medical Research Laboratories, University of Toronto (Toronto, 1968). C. B. F[arrar], “I remember J. G. FitzGerald,” American Journal of Psychiatry (Baltimore, Md), 120 (1963–64): 49–52. D. T. Fraser, “John Gerald FitzGerald (1882–1940),” RSC, Trans., 3rd ser., 35 (1941), proc., app.B: 113–15. M. L. Friedland, The University of Toronto: a history (Toronto, 2002). Jennifer Lem, “Dr. John G. FitzGerald: Canada’s public health care visionary” (research paper prepared for the Museum of Health Care, Kingston, Ont., 2006). Univ. of Toronto, President’s report (Toronto, 1914–40; annual reports of the director of the Connaught Laboratories; copies at UTARMS).

Cite This Article

James FitzGerald, “FITZGERALD, JOHN GERALD,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 22, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/fitzgerald_john_gerald_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/fitzgerald_john_gerald_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | James FitzGerald |

| Title of Article: | FITZGERALD, JOHN GERALD |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2018 |

| Year of revision: | 2018 |

| Access Date: | February 22, 2026 |