Source: Link

FRANÇOIS, LUC (baptized Claude), Recollet friar, painter, and architect, son of Mathieu François, “maître-saîteur” or cloth manufacturer, and of Perrette Prieur; b. at the beginning of May 1614 in the city of Amiens in Picardy; d. 1685 in Paris.

It was not by chance that, when they returned to New France in 1670, the Recollets included in their number an artist who was also an architect and a painter. In this order of Friars Minor as well as in the other orders, it was traditional that each monastery should be self-sufficient in artistic as well as in material matters. This tradition was maintained among the Recollets of New France until the disappearance of the order in the year 1813. Let us mention in passing Father Augustin Quintal*, a painter and architect, Father Juconde Drué*, an able builder, Brother Anselme (or Ignace) Bardou, a resourceful overseer, Father François Brekenmacher, a painter of portraits and religious pictures. The best known of these Recollet artists is undoubtedly Brother Luc.

Little is known of the early years of Claude François, except the account of an accident which probably was a determining influence in his life. One day – 25 April 1630 according to one chronicle – “this young man who, in accordance with his disposition and the humour of his age, delighted in riding, was proudly taking a horse to water near the Moucreux bridge [at Amiens, on the Somme], where, through a mistake on the rider’s part, the animal got out of its depth and was carried away with its rider; thus, seeing himself in such obvious and manifest danger and having already gone under the surface several times without leaving his mount, he remembered to call upon Notre-Dame-de-Foy, begging her to save his life . . . ; then, letting the horse go, without his knowing at what moment or by what means, he slipped underneath the grating and between the posts and the barrier which block the aforesaid bridge, through which one cannot imagine how a man could pass, much less a horse; then coming to the surface of the water on the other side of the bridge and being out of danger, with the horse swimming after him, he realized that he was outside the city in the direction of the suburb. . . .” “For such a signal favour,” adds the chronicler, Claude hastened with his mother to give thanks to Notre-Dame-de-Foy in the church of the Augustinians. Later, when he had become a member of the Recollet order, he was to recall this accident in one of his most charming pictures (in the church of Neuville-lès-Loeuilly, near Amiens).

At the time of the accident at the Moucreux bridge, Claude François had for some years been studying drawing and painting. He probably took some lessons from one of the itinerant artists who, in the reign of Louis XIII, used to stay for longer or shorter periods in the different cities of the kingdom. Not satisfied with this, he tried his luck in Paris. In 1632 he joined the studio of Simon Vouet, who had returned from Rome five years before. There he acquired, as did Le Brun, professional skill, some magical tricks of the trade, and a taste for Italian painting.

In 1635 Claude François was in Rome. He worked hard there for three or four years, made copies of the finest works that he could find, and compelled recognition from the critics for his character as much as for his activity and his talent. We know who his idols were: Raphael, Francesco da Ponte, Guido Reni, Guercino, Honthorst, Caravaggio. He was never to forget them.

Claude returned to Paris probably in 1639. There he saw again his master Vouet, who presented him to Sublet de Noyers, superintendent of the king’s buildings. The superintendent’s great project was the decoration of the Galerie du Bord de l’Eau in the palace of the Louvre, and that of his château at Dangu. To direct this great enterprise he brought Nicolas Poussin back from Italy; then he enrolled young painters, giving preference to those who had studied in Rome. Thus Claude François joined the team working in the Louvre; as a result of his two years of work (1640–42) he obtained the title of “king’s painter.”

Upon the death of his mother (1644) he joined the Recollets of Paris; he made his profession there on 8 October of the following year and took the name of Brother Luc (Luke), undoubtedly in remembrance of the patron of artists. If Brother Luc had taken leave of the world, he had not given up painting. On the contrary, he pursued a double career as a painter of church pictures and as a teacher.

He decorated with great Franciscan compositions most of the Recollet chapels of the province of Saint-Denis: Paris of course, Melun, Sézanne, Chalons-sur-Marne, Saint-Germain-en-Laye, Rouen, Versailles. He also painted some portraits and some small pictures of an edifying nature, which he entrusted to the most skilful engravers of his time.

We know the names of some of his pupils: Louis de Nameur (1627–93), Roger de Piles, an art historian (1639–1705), Jacques Galliot (1640–?), Claude de Saint-Paul (1666–1716), Desmarets. These unfamiliar names of painters and engravers do not constitute any great glory for Brother Luc. Probably he had little free time for giving lessons to daubers of mediocre talent – except for Roger de Piles, whose writings do not lack precision.

In the spring of 1670 Brother Luc left Paris for New France. He was one of a group of six Recollets who, under the direction of Father Germain Allart, the future bishop of Vence, were going to raise from its ruins their monastery at Quebec. At the end of May they sailed from La Rochelle on the ship which bore the Intendant Talon. They landed at Quebec on 18 August.

The task which they were undertaking was greater than they had thought, for they found their monastery, which had been abandoned in 1629 after the capture of Quebec by the Kirkes, in such a dilapidated state that they had to rebuild it completely. They set to work resolutely, with the certitude of being able to count upon public generosity as well as upon the king’s gifts. On 22 June 1671 Jean Talon laid the foundation-stone of the chapel; in October Bishop Laval* celebrated mass in the church, which already had its roof.

This chapel, the oldest in Canada, still stands; it is the chapel of the Hôpital-Général. Brother Luc made the plans for it and sketched out the retable as it is today; he even painted the “Assumption” which adorns this Recollet retable, the first one belonging to the Canadian School. Brother Luc showed his skill in the general composition and in the fitting-together of the component parts.

Moreover, it is not the only work of architecture which he has left. The wing of the procurator’s office, in the seminary of Quebec, was erected in 1677–78 following his design. The retables of the chapels of the Recollets in Paris, Sézanne, and Châlons-sur-Marne are also among his most beautiful architectural works.

Of the retable in the Recollet chapel of Quebec it can be said that it enjoyed considerable popularity in New France. There are still a few others (in the Ursuline convent and in the Hôtel-Dieu in Quebec, at Verchères, at Sault-au-Récollet, at Ange-Gardien, etc.) which are masterpieces of composition and of wood-carving.

The Recollet artist produced a great deal during his 15-month stay at Quebec. After his departure in October 1671 he continued to paint pictures for the churches of New France, and even portraits; and a long time after his death, in 1817 to be precise, certain of his works, which had been removed from churches in Paris at the beginning of the Revolution, belonged to Abbé Philippe-Jean-Louis Desjardins* and were sold at Quebec as part of his collection of pictures.

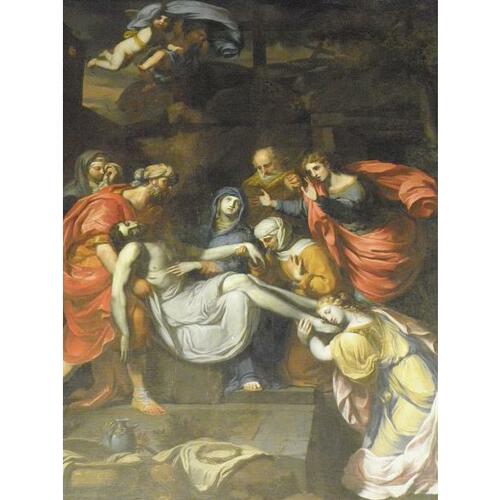

Let us mention first of all the works which he did during his stay in New France. I have already referred to the “Assumption” in the Recollet chapel. Other pictures by Brother Luc were to be seen there: for example, an expressive head of Saint Francis of Assisi, which is today in Montreal. The other pictures were taken in 1693 to the Recollet chapel in the Upper Town; they were destroyed in the fire on 6 Sept. 1796. The “Holy Family” which he painted in 1671 for the cathedral of Quebec was destroyed in 1759, along with a “Descent from the Cross.”

Fortunately, however, all was not destroyed. The “Guardian Angel” in the church of the same name (Ange Gardien) is one of the artist’s most harmonious compositions; the serenity of the expressions in this picture and its delightful colouring make of it a masterpiece. The two expressive heads in the church of Saint-Joachim – “Jesus as a Young Man” and the “Virgin of Sorrow” – are works of edification, as are other works of the same sort that we are acquainted with through prints. But the “Holy Family” in the church of the same name (Sainte-Famille, Île d’Orléans) recalls the nostalgic pictures which the “Poverello” suggested to the Recollet painter. I could say the same of the “Holy Family à la Huronne” (Ursuline convent in Quebec), of a “Nun Hospitaller nursing Christ in the figure of a Patient” and two “Ecce Homo” (Hôtel-Dieu in Quebec). These works do not necessarily possess great originality, but they are touching, naïvely expressive, bursting with tenderness. Other pictures preserved in the Ursuline convent, particularly “Tobias and the Angel,” do not display the same skilful touch.

I do, however, discover the nostalgic expression of the subjects again in the two compositions that Brother Luc painted in 1677 for the church of Sainte-Anne de Beaupré – “Saint Joachim and the Virgin” and the “Madonna and Child.” In these pictures all is restrained affection and grief: Saint Joachim and the Virgin, one might say, have a presentiment of the future and seem to see in the distance the cross of Golgotha. The artist often stressed this sentimental note. In the museum in Amiens, for example, an ex-voto represents the Madonna holding her child, to whom an angel descending from heaven is offering a cross. The picture bears the phrase: “Croix aimable à Jésus quoiqu’ignominieuse” – the Alexandrine line formed by the French title plays upon the name of the donor, François Quignon.

In the church of Saint-Philippe at Trois-Rivières is to be seen an immense ex-voto with rather gorgeous colours. It represents the Immaculate Conception. On the left a cherub holds a lance and shield, upon which can be read ipsa conteret caput nunc; on the right are the kneeling donors. The face of the donor’s wife recalls strangely that of Mother Catherine de Saint-Augustin [see Simon]. The Recollet painter had already chosen this emaciated face to use in the “Nun Hospitaller nursing Christ in the figure of a Patient.” In still another picture, “The Last Communion of Saint Catherine of Siena,” we find again the features and the expression of the portrait of Mother Catherine de Saint-Augustin, which Father Hugues Pommier painted in 1668. We are obliged to believe that Brother Luc had fallen under the spell of the sorrowful expression of the nun on her deathbed. This “Last Communion of Saint Catherine of Siena” is one of the two paintings which came to us from Paris with the Desjardins collection in 1817. The other is “Christ dictating to Saint Francis the Statutes of his Order”; it dates from 1679 and was painted for the Recollet chapel in Paris; a replica exists in the former chapel of the Recollets in Sézanne.

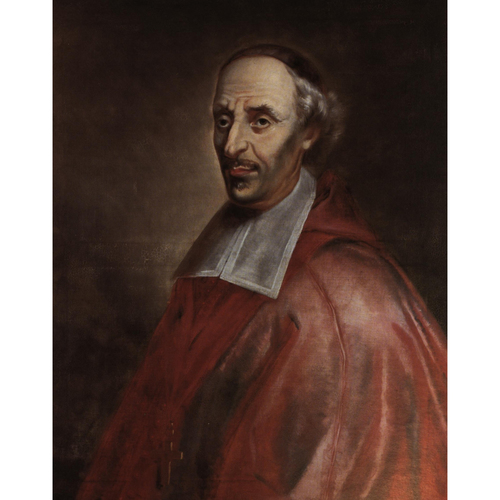

In the Recollet’s works are included some painted portraits. Two of them are at Quebec: “Jean Talon” in the Hôtel-Dieu, and “Bishop Laval” in the seminary. They date from the years 1671–72. Bishop Laval has a serious, slightly frowning expression. Talon, on the other hand, is smiling; in any event he does not have the stiff and somewhat pretentious expression which characterizes the copies that have been made of this lifelike portrait.

Our artist returned to France in the autumn of 1671 and the following year he received his teaching certificate for the monastery at Sézanne in Champagne. There he painted some ten pictures for the chapel and one portrait, that of the lawyer Charles Poullet. Returning to Paris in 1675, he continued to occupy himself with painting. But he conceived the idea of interesting himself in the Canadian missions. He constituted himself their advocate and agent in Paris, writes the editor of the Mortuologe. He had interviews with Colbert; he transmitted to the bishop of Quebec the minister’s intentions concerning the role of the Recollets in New France; finally, he undertook to find recruits for the needs of the Church in Canada.

In 1684 the monk left his studio, never to see it again. Nor do the documents mention him again, except to announce his death: he died peacefully on 17 May 1685.

ASQ, MSS, 200, Mortuologe des Recolets. BN, Estampes, Da. 40. Boitel, Annuaire du département de la Marne pour 1850–1851 (Châlons-sur-Marne, 1851). Charles-Philippe Chennevières-Pointel, Recherches sur la vie et les ouvrages de quelques peintres provinciaux de l’ancienne France (4v., Paris, 1847–62), III, 305–6. Florent Lecomte, Cabinet des singularitez d’architecture, peinture, sculpture et graveure (2e éd., 3v., Bruxelles, 1702). Hugolin Lemay, “Un peintre de renom à Québec en 1670: le diacre Luc François, récollet,” RSCT, 3d ser., XXVI (1932), sect.i, 65–82. Gérard Morisset, La vie et l’œuvre du Frère Luc (Québec, 1944). Roger de Piles, Abrégé de la vie des peintres, avec des réflexions sur leurs ouvrages (Paris, 1715).

Revisions based on:

Laurier Lacroix et al., Les arts en Nouvelle-France (Québec, 2012).

Cite This Article

Gérard Morisset, “FRANÇOIS, LUC (baptized Claude),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 1, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 16, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/francois_claude_1E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/francois_claude_1E.html |

| Author of Article: | Gérard Morisset |

| Title of Article: | FRANÇOIS, LUC (baptized Claude) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 1 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1966 |

| Year of revision: | 2016 |

| Access Date: | February 16, 2026 |