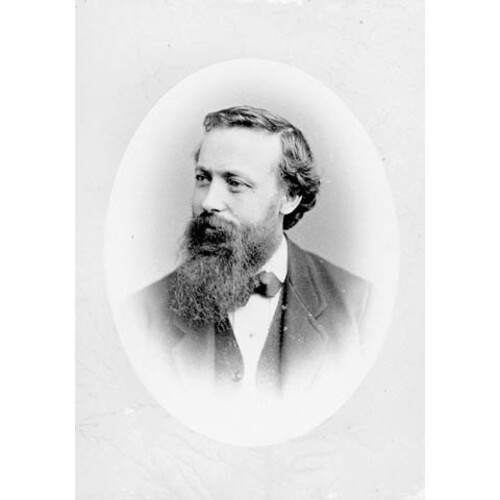

FRASER, CHRISTOPHER FINLAY, lawyer, politician, militia officer, businessman, and holder; b. 16 Oct. 1839 in Brockville, Upper Canada, son of John S. Fraser and Sarah M. Burke; m. 10 Jan. 1866 Mary Ann Lafayette, and they had a son and a daughter; d. 24 Aug. 1894 in Toronto and was buried in Brockville.

Christopher Finlay Fraser’s father, a Highland Scot and a shoemaker, immigrated to Upper Canada in the mid 1830s, settling in Brockville. In 1838 he married Sarah Burke, whose family had emigrated from County Mayo (Republic of Ireland). The eldest in a Roman Catholic family of ten children, Christopher received little formal education. By the time he was eight he had become a delivery boy for the reform Brockville Recorder, and later he was apprenticed to its publisher, David Wylie. Fraser remained a printer’s devil into his teens.

In 1859 he entered the law office of Albert Norton Richards, a prominent member of the local Reform establishment. Called to the bar in 1864, Fraser practised first alone and then with a Mr Mooney, and for a time in Prescott. His practice became better established when he formed a partnership in 1874 with Albert Elswood Richards. Fraser was appointed qc in 1876 and the following year Edmund John Reynolds joined the firm. Unlike Richards, who departed for Manitoba in 1880, Reynolds remained Fraser’s lifelong associate.

A rising and successful lawyer in Brockville, Fraser established a variety of local contacts. He served as an alderman from 1867 to 1873, gained a reputation as a lacrosse player, and became president of the Roman Catholic Literary Association. His marriage to the daughter of John Lafayette, a well-connected Protestant businessman, gave him entry to the most prominent circles in Brockville. He eventually acquired a lieutenancy in the local militia, a fine house on James Street, and a summer retreat at the fashionable Union Park resort near Brockville. Indicative of his widening circle of business associations was his participation in a financial reorganization of the Brockville and Ottawa Railway in the late 1860s. Fraser was given credit for working out a complex transfer of assets and liabilities among the provincial government, the railway (which held the rights to valuable timber limits), and the municipalities that held mortgages on the company. His involvement in railway finance was complemented by his longer affiliation with the Ontario Bank. In the depression of 1874–79 it became overextended. In the reorganization to save it Fraser became a director some time before November 1881. The bank recovered without further embarrassment during the time Fraser served on its board.

Though Fraser fit the Victorian pattern of moving from law and business into politics, his involvement with railways and banks was never the animus of his political activity. Fraser learned his organizational politics in the electoral campaigns of A. N. Richards, his Reform patron. He first ran for the provincial legislature in September 1867 as a Reformer for Brockville.

His candidacy was the product of two developments coincident with confederation. The Reform party was beginning a sustained effort to win back the Roman Catholic minority which had been alienated during the sectarian struggles of the 1850s [see George Brown*]. At the same time a new generation of Catholic lay leaders was seeking to persuade Irish Catholics to forsake their unrewarding support of the Conservative party in favour of a more independent political stance. Fraser became a link between these initiatives, and ultimately emerged as the most successful Catholic politician advocating an alliance with the Liberal party.

Fraser attended the Reform convention of June 1867 in Toronto where he and other Catholics were given a prominent place in an early public display of reconciliation. This effort was complemented by a convention of Catholics in Toronto the following month. While endorsing the Reform party in the coming federal and provincial elections, this meeting was not merely a partisan affair. It appealed to lay Catholics such as the politically independent Frank Smith* of London, who wanted more concrete political recognition of Ontario’s Catholic minority. Yet the move at the convention to establish an ostensibly neutral “Ontario Electoral Association” of Catholics became a pawn of partisan manœuvre. John O’Donohoe led those Catholics who had remained loyal to Reform, even under George Brown, to pack the meeting and endorse the Reform party in the coming election. As a Catholic of humble origin who had gained benefits from sympathetic Reform associations in Brockville, Fraser could pursue the interests of Irish Catholics and a Reform candidacy with no contradiction or conflict of interest.

The lay Catholic initiative at the July convention was condemned by the Catholic hierarchy and Fraser himself was defeated in Brockville. The consequent disruption of Catholic-Reform electoral efforts by no means ended the matter. Within two years Smith and O’Donohoe were again participating in a lay political initiative, the formation of the Ontario Catholic League. Fraser was a charter member of the league and no doubt he helped to keep it oriented towards the Reform party. Though outwardly bipartisan, the league inherently challenged the existing Catholic-Conservative alliance and its clerical sponsorship. More cautious than the Catholics had been in their effort of 1867, however, the league deferred to the bishops. Circumstances favoured such deferral, since the hierarchy in general, and Archbishop John Joseph Lynch* of Toronto in particular, had by 1870 become disenchanted with the Conservative party and the lack of recognition it afforded the Catholic minority. Conservative concessions, including the appointment of Smith to the Senate and John O’Connor* to the cabinet, prevented a breach in federal politics but did not alter the hierarchy’s disenchantment with the coalition government of John Sandfield Macdonald* in Toronto.

In this context Fraser made his second election bid as a Liberal, in 1871 in the provincial riding of Grenville South, but he was again defeated. Generally, however, the election marked a significant shift in partisan fortunes as Macdonald’s government came apart, especially with the defection of Catholic Richard William Scott*. The formation of a Liberal administration under Edward Blake* seemed to shift the balance of power in the direction sought by O’Donohoe and Fraser since 1867. When the Conservative incumbent for Grenville South died in 1872, Fraser’s bid for election benefited from the drive of the provincial Liberal organization to secure more Catholic mlas. Though his election was overturned because of irregularities, a subsequent by-election in 1872 saw him elected again. He was the only prominent member of the Ontario Catholic League in the Legislative Assembly, the league’s president, O’Donohoe, having been defeated in Peterborough East. Fraser secured re-election in Grenville South in 1875 and, when he was narrowly defeated there in 1879, he won the riding of Brockville, which he held again in 1883, 1886, and 1890.

When Fraser entered the assembly in 1872, he had to establish a working relationship with both the politically active Archbishop Lynch, an Irish Catholic who invariably referred to Fraser as a “Scotch-Catholic,” and the new Liberal premier, Oliver Mowat*. Private bills to incorporate the Orange order, introduced by Conservative Herbert Stone McDonald in 1873, provided Fraser with a timely opportunity to prove his worth. Lynch, who chose to make the issue a test of his influence, bluntly informed Mowat that incorporation would end Catholic support for the government. Since it was impossible to stop the bill from passing, Fraser’s job was to articulate Catholic opposition from the government benches in order both to reassure Lynch and to give Mowat room to manœuvre. This he did very effectively, proving himself an able parliamentary speaker in his first serious debate. His careful argument was designed to defuse sectarian feelings by a highly partisan account of Conservative duplicity and of the procedure used to introduce the bill. As an expression of his confidence in Fraser, Lynch presented him with a picture of the fathers of the Vatican Council. Mowat was impressed too. He appointed Fraser provincial secretary on 25 Nov. 1873 and promoted him to the key spending portfolio, commissioner of public works, on 4 April 1874.

Fraser quickly established a reputation as a sound administrator and as “an enemy of waste and extravagance.” His 20-year tenure as head of the Department of Public Works, without any embarrassment or public scandal, contributed substantially to the record of the Mowat government. Fraser’s responsibilities included the supervision of dam, lock, and bridge projects; the construction and maintenance of provincial buildings; and the approval of grants for drainage programs and colonization roads into northern Ontario. The department also approved the disbursement of bonus money appropriated from the provincial railway fund by the Department of Crown Lands for railway construction. This check is an example of the precautions taken by the Mowat government to ensure tight administration and an orderly patronage system without scandals. Thus contractors were paid only for work done to standard.

In assuming his duties Fraser implemented a policy of rigid retrenchment after several years of rapid growth in departmental expenditures. Though his department’s budget did ebb and flow corresponding to the prospect of an election, expenditures did not rise above the figures of 1873 until 1889, midway through the construction in Queen’s Park of new parliament buildings. This project, from its inception in 1877 to its completion in 1894, posed the greatest challenge to Fraser’s administrative talents. Delay was explained in part by the disparity between the original appropriation in 1880 of $500,000 and the tenders, all of which exceeded $1,000,000. Building began in 1886. The government’s boast that the edifice was the only large contemporary public building constructed within its estimates overstates the case. In 1893 an additional appropriation was made to cover the final cost of $1,257,000. Fraser successfully defended the cost by claiming that the handsome building had been more economical than any of the comparable projects in Quebec and a number of American states. Although Fraser had to deal with partisan sniping over siting, design, and tendering, at no time did financial scandal or patronage become a public issue.

For a brief time Fraser’s duties included labour and factory legislation. He chaired a select committee to revise the Workmen’s Compensation for Injuries Act of 1886. The amendments passed on the recommendation of his committee in 1887 extended the act to railway companies and other employers even if they had their own voluntary insurance societies. However, they did nothing to lift the worker’s burden of civil action to prove negligence in order to secure damages from an employer. Fraser’s department was to have administered the pioneer Ontario Factories Act of 1884 once regulations for enforcing it were issued in 1887, but responsibility was transferred the following year to the Department of Agriculture. In any case innovative social legislation was not in keeping with Fraser’s political character: “He hated all meddling and mothering legislation,” Sir John Stephen Willison* later recalled.

Fraser was a brilliant if sometimes acerbic parliamentarian who had all the skills of debate, procedural manœuvre, and humour needed to command respect in the assembly. To the bemusement of his contemporaries, he coined the term “brawling brood of bribers” to describe the ill-conceived attempt by Conservative partisans in 1884 to buy enough Liberal back-benchers to defeat the government. On the serious side, Fraser supervised the furtive effort to entrap the Conservative culprits involved in that attempt [see Christopher William Bunting. He also chaired the private bills committee, where he had the delicate and important responsibility of managing the legislation for many private railway charters and bills of incorporation.

Besides his departmental and parliamentary responsibilities Fraser participated directly in organizational politics. He served as a regional coordinator for the Liberal party in both federal and provincial elections in the St Lawrence valley constituencies east of Kingston. This organizational role, however, was eclipsed by his position as representative Catholic in the provincial cabinet. The key aspects of his brokerage role after 1873 were performed quietly and in the shadow of the so-called Lynch–Mowat concordat.

To understand Fraser’s function it is necessary to appreciate the divided character of the Catholic minority in Ontario. Despite the notion of a “Catholic vote,” there were always partisan divisions. Reinforcing this pattern of rivalry were growing tensions between Irish Catholics and Franco-Ontarians (evident as early as 1883), factional differences over the strategies of the Irish nationalist cause, and a growing lay rebellion against presumed clerical leadership. At the same time the episcopate was divided over political alliances and how to apply papal directives. In particular, the pragmatic Archbishop Lynch clashed with the assertive ultramontane Bishop James Vincent Cleary of Kingston. A would-be broker had to juggle all these factions in the midst of an overwhelming Anglo-Protestant majority in Ontario.

Fraser’s appointment as a member of the cabinet was the outward symbol of Catholic political influence and the sine qua non of Lynch’s cooperation, but this did not make Fraser a cipher of the Catholic hierarchy. His role was multifaceted. He acted as a champion of Catholic rights in public debates: against Orange incorporation when the issue was revived in 1874; in favour of French-language instruction for Franco-Ontarians; against lay Catholic and militant Protestant attempts between 1878 and 1894 to impose the use of the ballot in electing separate school trustees; and in defence of the integrity of the separate school system. Less conspicuous but of considerable importance was Fraser’s role lobbying for legislative favours for the Catholic minority on separate school laws, marriage law amendments, and the distribution of grants to charitable institutions. On the last of these he drafted and introduced legislation. At a public banquet in 1879, an election year, the Liberal party honoured their Catholic minister. Fraser publicly appealed to Catholics for their support of the government as the best means to ensure Catholic minority rights and fair play by Protestants. Privately, prior to the election in June, he successfully pressured Mowat to recruit more Catholic candidates for the legislature.

As a Catholic member of cabinet Fraser was called upon to mollify aroused clerics when Mowat could not give them what they wanted, which happened frequently. In 1874 Fraser had counselled patience to Father John O’Brien of Brockville regarding marriage law amendments. Two years later, when Bishop John Walsh of London was dissatisfied with Lynch’s acquiescence to new school regulations, he wrote to Fraser. In 1879, again in correspondence with Walsh, Fraser upheld the adequacy of the separate school law amendments of the education minister, Adam Crooks*, and in 1886 he again reassured the London bishop of the soundness of the government’s decision to delay amendments to the separate school legislation.

On the other hand Fraser might also chart political strategies by which the hierarchy could achieve its goals. In the face of the agitation in 1878–79 for the ballot in separate school elections, the bishops (who strongly opposed the idea) deferred to Fraser’s proposal for a prompt counter-petition in early 1879 to give the government the leverage needed to resist the demand. In 1887, dealing again with lay commotion over the ballot, the bishops accepted his recommendation that they delay their planned petition campaign. Likewise, during the Toronto Mail’s crusade against Catholic separate schools in 1886, Fraser had been instrumental in formulating the public responses of bishops Walsh and Lynch.

Mowat and Lynch dealt directly in matters of patronage, but after 1885 Fraser seems to have become the regular conduit for patronage demands from Bishop Cleary of Kingston. This activity was only one dimension of Fraser’s dealings with this difficult and highly principled Irish ultramontane. As the campaign against separate schools heated up after 1885, Cleary found himself an unwilling ally of the provincial Liberals. They in turn found his dogmatic endorsements an embarrassment requiring repudiation. In this confusing situation Fraser served as the trouble-shooter who dealt with Cleary’s indignant demands for public retractions from Arthur Sturgis Hardy*, Mowat’s commissioner of crown lands, and from the Globe in the midst of the election campaigns of 1890 and 1894.

The most vital service Fraser ever rendered to the delicate Catholic-Liberal alliance involved Cleary and his reaction to the regulations made public in December 1884, by which, for the first time, there was to be an official selection of Bible readings and prayers for use in public schools, the so-called Ross Bible program. In preparing the regulations, Mowat and his minister of education, George William Ross*, had been careful to consult Lynch on the selection and secure his acquiescence to this Protestant initiative. Lynch made only a few minor suggestions, which were accepted. Mowat depended on him to ensure endorsement by his fellow bishops. When, on 31 December, Lynch tried to present the new regulations as a fait accompli that did not threaten Catholic rights or doctrine, Cleary led an episcopal rebellion on sound doctrinal grounds. He forced an isolated Lynch to accept a series of resolutions which repudiated the Ross Bible program, demanded an immediate meeting between Mowat and a delegation of bishops led by Cleary, and, failing cancellation of the program, threatened an appeal to Rome and a full public condemnation.

With Lynch and Mowat stalling for time in January 1885, Fraser was delegated to arrange a compromise that would satisfy Cleary, Walsh, and Bishop James Joseph Carbery of Hamilton but would avoid public loss of face for the government. Negotiating a partial settlement first with Cleary on 28–29 January, Fraser was able to get Walsh and Carbery to accept this compromise as the basis for a settlement, thereby manœuvring the more recalcitrant Cleary into acquiescence. Revised instructions to school inspectors, which effectively reversed the intent of two key provisions of the published regulations, gave the guarantees of non-participation by Catholic students and teachers that the bishops deemed essential. The settlement prevented an escalation of the sectarian controversy already defacing provincial affairs. As with most of Fraser’s activities, the fact that his intervention never became public is a measure of his political success.

The years following the Cleary crisis marked the pinnacle of Fraser’s political influence. As a Catholic-Liberal broker, he had outmanœuvred or outlasted all his potential provincial rivals. Catholic senators Frank Smith and John O’Donohoe (who had converted to the Conservative party in 1877–78), former mla John O’Sullivan, and the talented Toronto lawyer James Joseph Foy were able to keep most of Ontario’s Irish Catholics loyal to the Conservatives at the federal level but they could not challenge the Catholic-Liberal network managed by Fraser provincially. As a result of the incapacity in 1886 of Timothy Blair Pardee*, Mowat’s right-hand man, and his death in 1889, Fraser’s stature in the cabinet rose further. Ross and Hardy, Fraser’s only serious rivals as Mowat’s chief lieutenant, lacked the scope of his political talents as well as his experience.

Fraser’s effectiveness as a Catholic broker had also, however, set severe limits on his career by 1885. The rising tide of Anglo-Protestant bigotry made him the target for vicious partisan-sectarian appeals and constrained the public role he might play. He was even stoned by Protestant thugs when he participated in a Catholic procession in Toronto in the late 1880s. The partisan strategies of the Ontario Conservative party during that period consolidated the support of the Catholic bishops for the provincial Liberals, but also left Catholic Conservatives such as Foy free to appeal to on-going lay dissent from clerical leadership. Both the ageing Mowat government and Fraser became more reliant on a hierarchy of declining political influence. At the same time the militant Protestant reaction between 1884 and 1894 put the Liberal government on the defensive in, matters related to separate schools, a posture in which the bonds with the Catholic hierarchy were weakened. The untimely electoral interventions of Cleary in 1890 and 1894 did much to transform the Catholic-Liberal alliance into a burden for the Liberal party. All these developments made Fraser’s juggling act as a broker problematic once the Conservatives abandoned the no-popery cry.

The decisive factor, however, in the decline of Fraser’s influence was not the changing social and political circumstances in which he operated. His own “great capacity for work and passion for it” did him in. As he protested in August 1894, “I am not resigning my office but my office is making off with me.” Although reports of his poor health date back to at least 1877, overwork seems to have induced a turn for the worse in 1885–86. His heart condition apparently became acute and chronic about the time of the 1890 election campaign. He missed the session of 1892 in order to recuperate in the American southwest, and he had been subject to “fainting fits” for at least five years before 1894. Even so, Mowat was loath to part with so valuable a minister when he offered his resignation in 1891 and again in 1893.

Fraser agreed to stay on until the parliament buildings were completed. He therefore found himself participating in the legislative session of February–May 1894. Anticipating an assault on the separate school law by both the opposition and the Protestant Protective Association [see Oscar Ernest Fleming*], and with the endorsement of Richard William Scott, Wilfrid Laurier*, and a plurality among the Irish Catholic laity, Catholic Liberal James Conmee introduced a bill on 21 February providing for a secret ballot in elections for separate school boards when local ratepayers expressed their desire for it. In his last speech in the assembly, on 23 April, Fraser defended the integrity of the separate school system and the clerical role in its management without repudiating the voluntary principle of Conmee’s bill. The effort produced the “pathetic scene” of the once-great debater breaking down three times before giving up the attempt to state his whole position. Altogether Fraser’s final performance, the passage of the bill, and the defeat of two motions for a compulsory ballot (one by Conservative leader William Ralph Meredith*, the other by Peter Duncan McCallum, a member of the Protestant Protective Association) enabled the government to enter the election campaign well positioned to straddle this divisive issue. Fraser ended his parliamentary career as he began it, a Catholic-Liberal broker.

On 28 February Mowat had formally announced that Fraser was resigning from the cabinet but would remain commissioner of public works. To add to the novelty of this arrangement, Meredith requested that the government find an “important” posting appropriate to Fraser’s great talents. Resigning from public works on 30 May, he assumed the duties of inspector of registry offices in June but collapsed in his office from a heart attack in August after returning from a field trip. He died on the 24th and his body lay in state for a day at Queen’s Park.

All contemporary eulogies agreed on three points: Fraser was an excellent parliamentarian, a worthy and independent representative of the Catholic minority, and an efficient administrator who was unimpeachably honest in his public life. These assessments are an understatement for they overlook the hidden dimension of his career. Sir John A. Macdonald had observed as early as 1882 that Mowat’s “strength has hitherto been Fraser, the Archbishop [Lynch] and the Catholic vote.” As Macdonald so well understood, Fraser made a distinct contribution to Mowat’s political longevity. It seems a fitting tribute that his initials are carved into the stone capping of the six columns to the right of the main entrance of the parliament buildings. Like the role which he played during 25 years of public life, they remain almost invisible.

Three of Fraser’s speeches have been published: Speech of the Honourable C. F. Fraser, delivered in the Legislative Assembly of Ontario, February 25th, 1878, on the Orange Incorporation Bill (Toronto, 1878); The Fraser banquet: magnificent tribute of respect and confidence rendered to the Honorable C. F. Fraser, commissioner of public works . . . ; eloquent speech by the guest of the evening ([Toronto, 1879]); and A speech delivered by Hon. C. F. Fraser, commissioner of public works, in the Legislative Assembly, March 25th, 1890, on separate schools and the position of the Roman Catholic electors with the two political parties (Toronto, 1890).

AO, MU4756, no.7. ARCAT, L, AD01, 03, AE12, AF02, AG04, AH21, AO03, 14, 20, 27–28, AP01; W, AB02, AD01; also some Walsh docs. filed in L, AO27. Arch. of the Archdiocese of Kingston (Kingston, Ont.), DI (E. J. Horan papers, corr.), 5C29, 37, 8C41,13C4, 11ED11; FI (J. V. Cleary papers, corr.), 1C13–14, 16, 23, 25, 2C1, 27, 41, 8ER3–4. NA, MG 27, I, E12. St Francis-Xavier Roman Catholic Church (Brockville, Ont.), Reg. of baptisms, marriages, and burials. Brockville, the city of the Thousand Islands, comp. Thomas Southworth with pen sketches by F. C. Gordon (Brockville, 1888). Brockville Evening Recorder, 25 May 1893, 31 Aug. 1894. Dent, Canadian portrait gallery. A. M. Evans, “Oliver Mowat and Ontario, 1872–1896: a study in political success”

Cite This Article

Brian P. N. Beaven, “FRASER, CHRISTOPHER FINLAY,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 27, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/fraser_christopher_finlay_12E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/fraser_christopher_finlay_12E.html |

| Author of Article: | Brian P. N. Beaven |

| Title of Article: | FRASER, CHRISTOPHER FINLAY |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1990 |

| Year of revision: | 1990 |

| Access Date: | February 27, 2026 |