Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

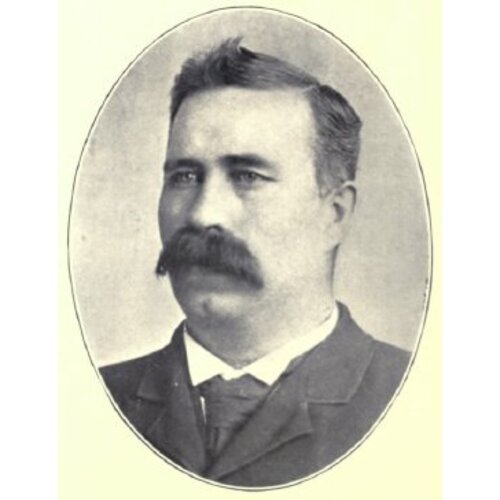

FRASER, DUNCAN CAMERON, lawyer, politician, judge, and lieutenant governor of Nova Scotia; b. 1 Oct. 1845 in Brooklyn (Plymouth), Pictou County, N.S., eighth child and fifth son of Alexander Fraser (Alasdair an Ceannaiche) and Ann Chisholm; m. 24 Oct. 1878 Bessie Grant Graham in New Glasgow, N.S., and they had four sons and three daughters, including James Gibson Laurier and Margaret Marjory, who were killed in World War I, and Alistair, who was lieutenant governor of Nova Scotia from 1952 to 1958; d. 27 Sept. 1910 at his summer home in Fort Point, near Guysborough, N.S.

Little is known of Duncan Cameron Fraser’s early years except that he attended school in New Glasgow. To help finance his three terms at the Normal School in Truro in 1863 and 1864 he taught intermittently in a log school-house at the head of the East River. Fraser entered Dalhousie College in 1869 and earned a ba in 1872. During his freshman year he helped edit the fledgling Dalhousie Gazette, the oldest college newspaper in Canada. Upon graduation he was articled for a period to James McDonald*, mp for Pictou. He was admitted to the provincial bar on 26 July 1873 and made a notary on 6 October. Fraser began his practice in New Glasgow, where he drafted the act of incorporation and served as the first town clerk, between 28 Jan. 1876 and 31 July 1877.

On 18 Feb. 1878 Fraser was named to the Legislative Council by the government of Philip Carteret Hill*, but he resigned to contest the Guysborough County seat for the Liberals in the provincial election of September 1878. A local party dispute may have caused his defeat. The set-back seemed to change Fraser’s priorities, since after the election he began to take a more active interest in his community and profession. On Sundays he sang in the bass section of the James Presbyterian Church choir with Graham Fraser*, whose Nova Scotia Forge Company he represented the balance of the week. Other clients included the shipping company of James William Carmichael and the Halifax and Cape Breton Railway and Coal Company. A school commissioner for south Pictou, Fraser served as a town councillor for New Glasgow in 1878 and as its mayor in 1882 and 1883. In 1886 he was a founding director of the Halifax Ladies’ College. Masonic, temperance, and curling activities also kept him in the public eye.

In 1886 politics beckoned again. Premier William Stevens Fielding* made an offer of a seat on the Legislative Council, but because Fielding supported the repeal of confederation Fraser spurned his advances. On 23 Feb. 1888, however, Fraser became government leader in the Legislative Council and minister without portfolio. Twenty-eight days before the federal election of 1891, he accepted the Liberal nomination for Guysborough after the incumbent was forced to withdraw because of ill health. He won by 86 votes. The “Guysborough Giant,” six feet four inches tall and weighing 350 pounds, became an instant success in Ottawa with his good humour, fund of stories, fine singing voice, and command of Gaelic. Active in parliament, D. C., as he was known, was in constant demand as a speaker. The Liberal leader, Wilfrid Laurier*, was on excellent terms with Fraser and in 1894 told J. W. Carmichael that “as a stumper he is our best man.” The following year Fraser toured western Canada with him.

The Liberal victory of 1896 was, however, followed by a set-back in Fraser’s political career. Denied a position in Laurier’s cabinet when Fielding and Frederick William Borden* were chosen to represent Nova Scotia, he was quick to express his disappointment. The sulking hulk was difficult to hide and Laurier and Fielding tried without success to get him an appointment west of the Rockies. But Fraser enjoyed people and politics too much to remain angry long. He successfully contested Guysborough in the election of 1900, winning by the largest majority of his career. In 1901 he became chairman of the House of Commons public accounts committee.

By 1904, for unknown reasons, the government was seeking an opportunity to move Fraser on. In January Fielding advised Laurier that “after what has happened respecting our friend D. C. it would be exceedingly awkward to have him sitting in Parliament at the coming session.” There were then three vacancies on the Supreme Court of Nova Scotia, and since Fraser evidently had the fewest enemies of any candidate and a seat the government felt it could win in a by-election, on 10 Feb. 1904 he was named to a judgeship. At least one Nova Scotian mp considered his appointment “a misfortune.” Fraser was undoubtedly able, but he did not possess the application required of a judge. A later Supreme Court justice wrote that “he was not prepared for the Bench, and the study entailed was distasteful to him.”

After just over two years as a judge Fraser resigned, and on 27 March 1906 he was appointed lieutenant governor of Nova Scotia, succeeding Alfred Gilpin Jones. The circumstances of this appointment were also murky; apparently there had been complaints about Fraser’s performance on the bench, and Premier George Henry Murray* put pressure on him to take the position, which he later told Laurier that he “did not seek, [and] did not want.” Much to Fraser’s annoyance, the leader of the federal Conservatives, Robert Laird Borden*, hinted that there was an arrangement whereby Fraser would return to the Supreme Court when his term expired.

Fraser was successful and popular as vice-regal representative but complained to Laurier that he found the position expensive. As he put it, “I am between the millstones, and even my corpulent frame cannot stand the eternal grinding.” At his first New Year’s Day levee he declined to wear the usual Windsor uniform and dispensed with the traditional “private entrée.” One newspaper claimed that he thereby did away with “150 years of solidified social sentiment and snobbery.” The rapid decline in his health in the summer of 1910 and his sudden death came as a shock to the province. In his last public appearance he spoke forcefully in support of the proposed union of the Presbyterian and Methodist churches.

Fraser’s political career was to some extent governed by a series of roads not taken or doors which would not open. He boasted proudly that he held radical views on free trade, and of his liberalism there was no doubt. He opposed restrictions on Chinese immigration; on proposed Lord’s Day legislation he was “not in sympathy with laws that attempt to make men moral.” His greatest success, however, was as lieutenant governor, and he enjoyed the opportunities to meet and entertain fellow Nova Scotians. Despite his exalted position, Fraser remained a down-to-earth man, and of all the eulogies he received he might most have appreciated the words of a voter of Guysborough County. “We like Mr. Fraser, he’s like one of us. He came into my house, sat down, lit his pipe, and spit on the floor just like one of the family.”

An excellent posed photograph of Duncan Cameron Fraser is in PANS, Photograph Div., O/S, no.15.

PANS, MG 100, 143, no.32. Eastern Chronicle, 12 Sept. 1895, 30 Sept. 1910. J. M. Cameron, Political Pictonians: the men of the Legislative Council, Senate, House of Commons, House of Assembly, 1767–1967 (Ottawa, [1967]). “Masonic grand masters of the jurisdiction of Nova Scotia, 1738–1965,” comp. E. T. Bliss (typescript, n.p., 1965; copy at PANS).

Cite This Article

Allan C. Dunlop, “FRASER, DUNCAN CAMERON,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 21, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/fraser_duncan_cameron_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/fraser_duncan_cameron_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | Allan C. Dunlop |

| Title of Article: | FRASER, DUNCAN CAMERON |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1994 |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | December 21, 2025 |