Source: Link

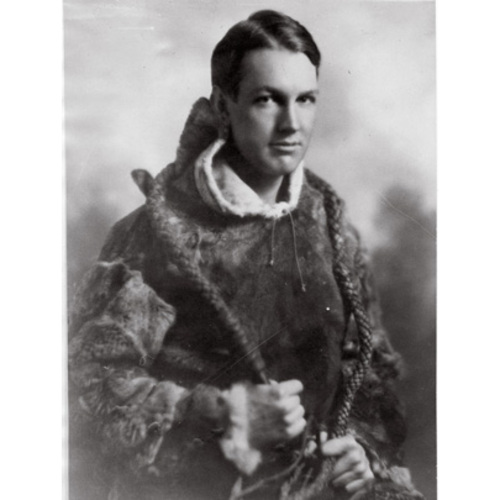

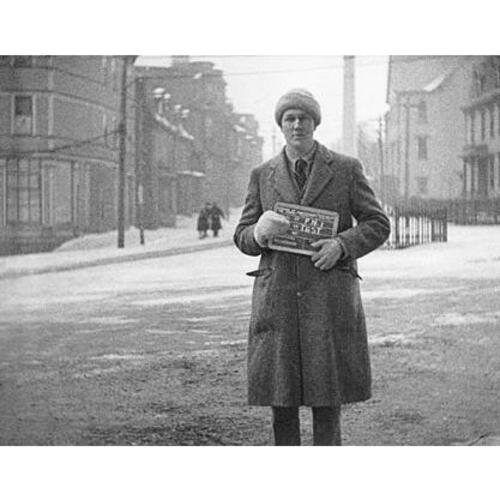

Frissell, Lewis Varick, social activist, explorer, and film-maker; b. 29 Aug. 1903 in New York City, son of Lewis Fox Frissell and Antoinette Wood Montgomery; d. unmarried 15 March 1931 in an explosion near the Horse Islands, Nfld.

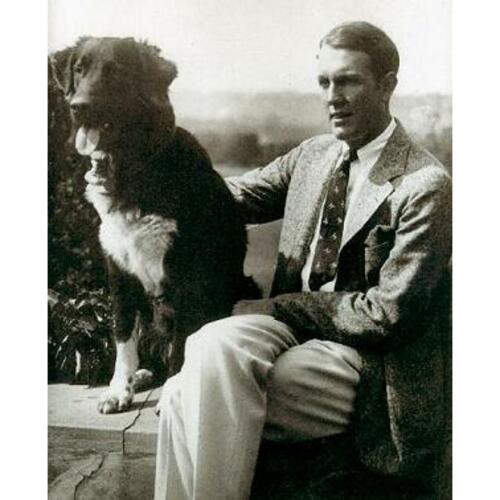

Varick Frissell was born into a wealthy New York family; his paternal grandfather was a president of the Fifth Avenue Bank, and his father, a physician, was to have a long career at St Luke’s Hospital and Columbia University. Varick grew up with a confidence and athleticism that were nurtured by his privileged background. After being privately educated at Allen-Stevenson School in New York and Choate School in Connecticut, he entered Yale University in New Haven during the fall of 1922. Handsome and well over six feet tall, he excelled in a range of activities. Besides taking part in rowing and water polo, he was a member of the Glee Club, the University Choir, and the Whiffenpoofs, an a cappella group. He also contributed to the student publications the News and the Literary Magazine.

Like many young men from similar backgrounds, he was attracted by adventure and the prospect of doing something meaningful. After hearing a lecture by medical missionary Wilfred Thomason Grenfell, Frissell had realized that he could satisfy both interests, and from September 1921 until April 1922 he had worked in Labrador as a volunteer for the International Grenfell Association. He drove a dogsled to deliver medical supplies during the winter. While at university he was secretary, treasurer, and president of the Yale Grenfell Association. In his summer vacations he returned to Newfoundland and Labrador, where he worked as a hand on the hospital boat Strathcona II. He helped establish a water supply in St Anthony and was a founder of the Yale School, which opened in 1926 at North West River. Travelling with Grenfell through the United States on fund-raising trips, Frissell displayed his still photographs and film footage. Grenfell described him as “naturally attractive to everyone.… His size, his strength and his reactions to all the impulses of life were just such as I have always associated with those I love best.”

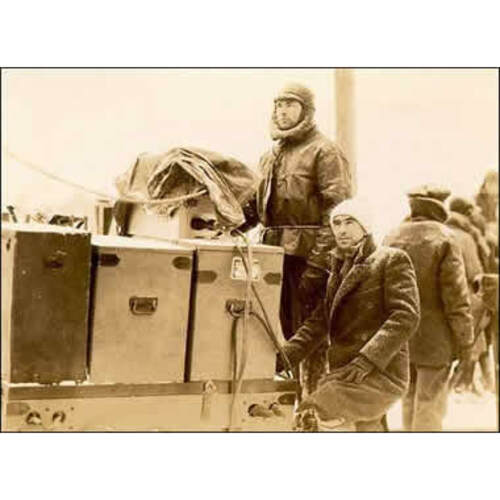

While he was growing up Frissell had made home movies, displaying a flair for documenting everyday life and work. This interest was one of the reasons why Grenfell encouraged him to travel by canoe up the Hamilton (Churchill) River, a journey that Frissell estimated at 300 miles. Besides taking still and moving pictures that could be used in lectures, he wanted to learn more about the potential for employing Labrador’s resources to improve the economy. During this 1925 trip Frissell shot the first film of the Grand (Churchill) Falls, explored the “unknown channel” noted by geologist Albert Peter Low*, naming it the Grenfell (Unknown) River, and discovered and named the Yale (Thomas) Falls. The footage was released as a short documentary entitled The lure of the Labrador, which had a modest success in 1925. He graduated with a bachelor of philosophy the following year. In 1927 Frissell published an account of his inland expedition in the Geographical Journal (London) and was appointed to the Royal Geographical Society. He spent six weeks (February to April) working aboard a sealing steamer and shooting film when he was not on duty. He was fascinated by the adventure of the hunt, but felt that it was “no fun killing seals.” About 40 minutes long, The swilin’ racket (called The great Arctic seal hunt when it was released the following year) was created from some 10,000 feet of film. Frissell became a director of the Grenfell Association of America in 1928.

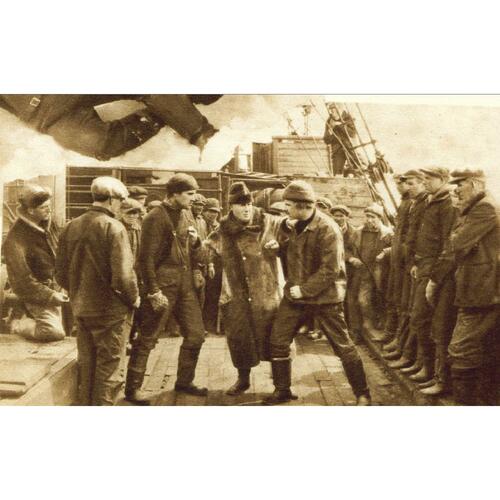

He then worked as a cameraman for Robert Joseph Flaherty* (famous for 1922’s Nanook of the north, filmed in Canada) on Acoma. Shot in 1928–29 in the southwestern United States and combining documentary footage of the natives with a dramatic plot, the film was never released because of Hollywood’s transition to movies with sound, and the uncompleted footage was later lost. Frissell spent some time in Mexico, selling film footage of the Cristero War (a popular uprising against anti-clericalism) to newsreel companies in 1929. The next year, intending to make a feature-length film on the seal hunt, he formed the Newfoundland-Labrador Film Company, incorporated in Delaware, with money from American and Newfoundland investors. He received no salary, agreeing to be paid in company shares if the film was a success. After securing a distribution deal with Paramount Pictures, he began shooting in February. Paramount insisted that Frissell hire an experienced director and writer to emphasize the romantic interest. Garnett Weston wrote a melodramatic script about two men in love with the same woman. The director was George Melford; of the non-professional actors, the most notable was Captain Robert Abram Bartlett*, who played the ship’s commander. This film, for which the title White thunder was eventually chosen, was one of the earliest sound-synchronized motion pictures made on location and the first in Canada. Frissell’s achievement was even more remarkable because of the arduous conditions aboard the vessel and on the ice. The first screening, early in 1931, confirmed that the film’s strength was the real-life scenes contributed by Frissell rather than the awkward love story. Paramount declined to distribute the film.

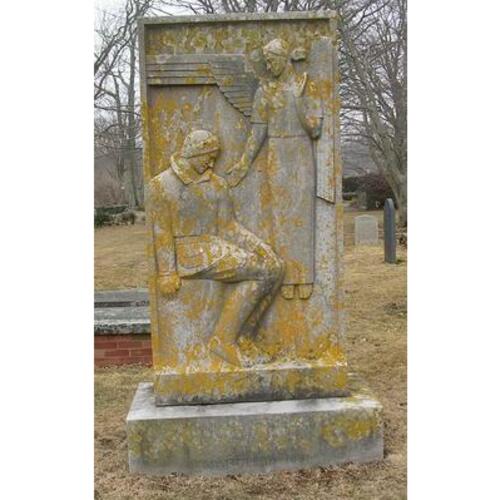

Intending to shoot additional material that he hoped would salvage White thunder, Frissell engaged the steamer Viking. Commanded by Captain Abram Kean Jr, the ship left St John’s on 9 March. The voyage was rough, and Frissell and his team were described as “sailors of the finest quality” by Clayton Leroy King, the radio operator. The ship carried explosives to deal with ice jams, and Frissell was concerned that the crew were insufficiently cautious. On 15 March, while making a “warning” sign, he ordered that some old, damaged flares be thrown overboard. When the bosun objected that he wanted to try some experiments, Frissell replied, “If you fool with them we’ll all be blown to Hades before daylight.” The man picked up the flares and left the room. A few moments later, an explosion heard eight miles away blew out the stern of the ship. Frissell was one of the 27 men, out of 143, who were killed. Over the next few days, the survivors, some terribly injured, were picked up by rescue ships or made their way over the ice towards land. Frissell’s father organized and financed an aerial search, but his body was never recovered. Taking advantage of the publicity, independent distributor J. D. Williams quickly released the film as it had first been seen, using the title The Viking.

Lewis Varick Frissell is the author of two articles: “They found the falls that rival Niagara,” Canadian Magazine, 65 (1926), no.9 (September 1926): 6–7, 39–42 and “Explorations in the Grand Falls Region of Labrador,” Geog. Journal (London), 69 (January–June 1927): 332–40. He directed, photographed, and edited two films, The lure of the Labrador (released in 1925; re-released as The lure of Labrador in 1926) and The swilin’ racket (1928; also known as The great Arctic seal hunt). In addition, Frissell wrote and produced the film The Viking, which was released after his death in 1931.

“Varick Frizzell tells of beauty of giant river,” Financial Post (Toronto), 19 Oct. 1928: 15–16. “Young explorer films seal hunt,” New York Times, 29 April 1928: X8. Encyclopedia of Nfld (Smallwood et al.), 2: 68. “Feared twenty perished in Viking disaster”: www.ancestraldigs.com/SHIPS/shipVikingPt1.htm (consulted 11 Feb. 2013). W. [T.] Grenfell, Forty years for Labrador (Boston, 1932). History of the class of 1926, Yale College …, ed. O. B. Lord (New Haven, Conn., 1926). C. L. King, “Last voyage of the Viking,” in The book of Newfoundland, ed. J. R. Smallwood et al. (6v., St John’s, 1937–75), 1: 76–85. Mark Langer, “Flaherty’s Hollywood period: the Crosby version,” Wide Angle (Athens, Ohio), 20 (1998): 38–57. Tom McSorley, “Search and rescue: restoring Varick Frissell’s The Viking,” Take One (Toronto), 13 (June–September 2004), no.46: 19–22. Peter Morris, Embattled shadows: a history of Canadian cinema, 1895–1939 (Montreal and Kingston, Ont., 1978). White thunder, directed by Victoria King (film, Toronto, 2002). Yale Univ., Obituary record of graduates deceased during the year ending July 1, 1931 (New Haven, 1931): 186–88.

Cite This Article

Jeff A.Webb, “FRISSELL, LEWIS VARICK,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 1, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/frissell_lewis_varick_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/frissell_lewis_varick_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Jeff A.Webb |

| Title of Article: | FRISSELL, LEWIS VARICK |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2013 |

| Year of revision: | 2013 |

| Access Date: | March 1, 2026 |