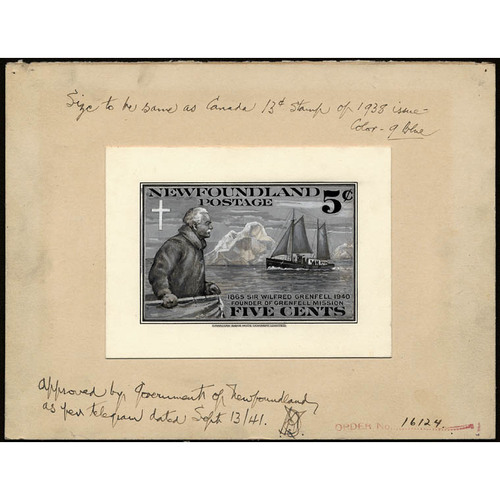

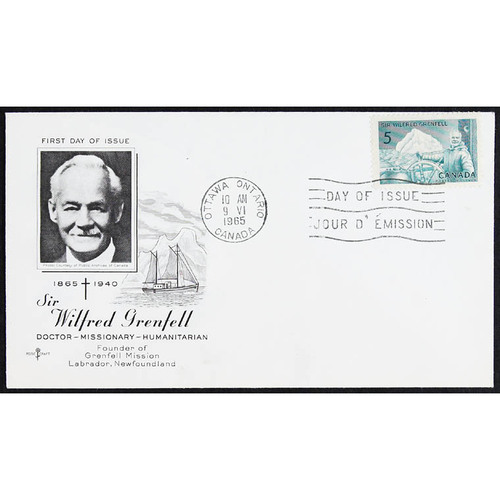

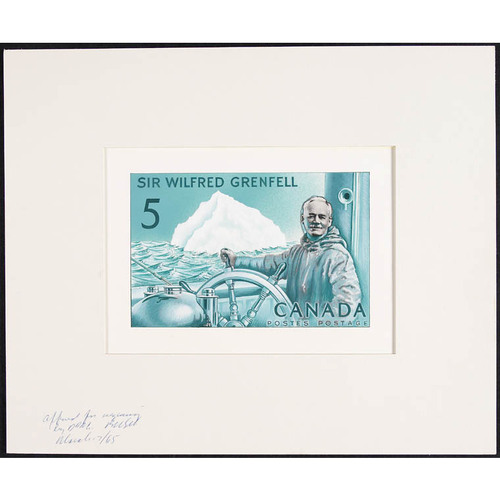

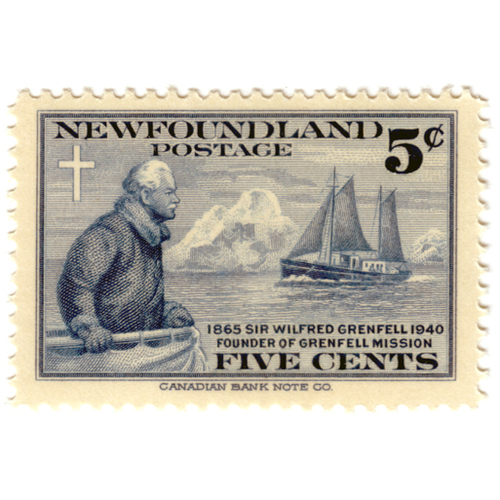

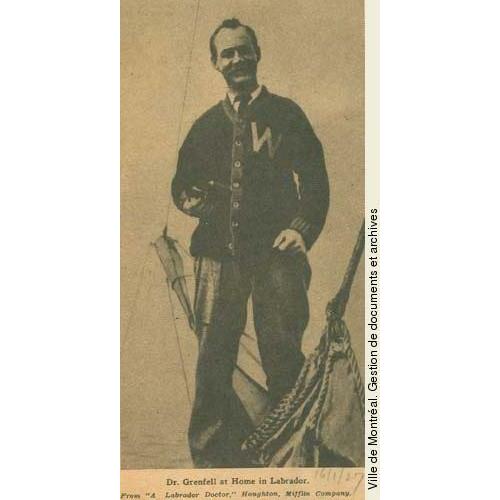

GRENFELL, Sir WILFRED THOMASON, physician, medical missionary, social reformer, and author; b. 28 Feb. 1865 in Parkgate, near Neston, England, second son of Algernon Sidney Grenfell and Jane Georgiana Hutchinson; m. 18 Nov. 1909 Anna Elizabeth Caldwell MacClanahan in Chicago, and they had two sons and a daughter; d. 9 Oct. 1940 in Charlotte, Vt.

Behind the Dr Charles S. Curtis Memorial Hospital at St Anthony, Nfld, stands a rock face bearing six brass tablets. One locates the ashes of Sir Wilfred Grenfell, the British physician whose extraordinary accomplishments in Newfoundland and Labrador embraced the building of hospitals, orphanages, schools, and small industries where none had existed before. The tablet registers Grenfell’s life without any conventional Christian iconography or sentimental language, giving only a name, a date, and an inscription, “Life is a Field of Honour.” Grenfell was one of the last of the spiritual adventurers, the manly Christians who carried the code of service into the remote places of the earth at a time when such a philosophy of life was still possible.

Wilfred Grenfell and his three brothers were raised in the village of Parkgate, where their father, a Church of England minister, was headmaster and proprietor of Mostyn House, a boarding school for boys. In 1879 Wilf was sent to Marlborough College, a tough public school that encouraged the social and religious attributes of masculinity advocated by such writers as Thomas Carlyle, Charles Kingsley, and Thomas Hughes. The young Grenfell revelled in the physicality of the school’s regime, but his father grew dissatisfied with the progress of his studies and in 1881 took him to read with a private tutor for the London matriculation while the young man pondered what he might do with his life. He considered the army, then the church. During an interview with the village doctor in Neston, he became consumed with the idea of being a physician, and in February 1883 he entered the London Hospital Medical College. At the same time, his father, who was growing unstable under the stresses of school life, leased Mostyn House and accepted the chaplaincy of the London Hospital, where his condition worsened. In 1885 he was committed to an asylum, and two years later he died by his own hand.

At this stage, Wilfred already showed tendencies for which he would later be recognized. Although he enjoyed medicine, especially the diagnostic techniques of Sir Andrew Clark and the surgical practices of Frederick Treves, he often absented himself from lectures and gave much of his spare time to cricket, rugby, and rowing. He also played football for Richmond. He filled out his schedule by running a gymnasium and a Sunday school out of his house. During vacations, he organized summer camps in Wales for boys from London’s East End. “He always aimed at the big things in life,” wrote his fellow student Dennis Halsted. “The details … he left to others less competent.” By publishing his own account of his accomplishments in the Review of Reviews (London), he exhibited another aspect of his personality: the need to publicize and promote his work.

More profound was a religious experience Grenfell claims to have had in 1885, during his second year of medicine. As he returned one night from treating a case in Shadwell (London), he was drawn to a tent meeting conducted by the American evangelists Dwight Lyman Moody and Ira David Sankey. Moved by their simple formula for living the Christian life, he went away convinced that he ought to devote his energies and medical training to what Jesus would have done if he had been a doctor. At a subsequent meeting, when the call came to “stand up” for Christ, he did so, determined to dedicate his life to practical service. In January 1888 he attained a licence from the Royal College of Physicians and conjoint membership in the Royal College of Surgeons. He then spent the fall term to no apparent purpose at Queen’s College, Oxford, where he earned blues for athletics. Though licensed, he failed the bachelor of medicine examination set by the University of London.

Meanwhile, something significant was happening. Treves had suggested to Grenfell that he put his training to use as a physician with the Mission to Deep Sea Fishermen, the newly formed society that operated among the North Sea fishing fleet and for which Treves himself was the medical adviser. This physical and practical challenge suited Grenfell perfectly and gave him an opportunity to preach the gospel. In its earliest days, the mission regarded itself primarily as an evangelical organization and only secondarily as a philanthropic and medical agency. By the end of 1887 it had eight smacks at sea and a growing corps of lay and ordained evangelists. In 1889 Grenfell, at 24, was appointed its first superintendent with responsibility for fleet maintenance. After establishing himself at Yarmouth, he recognized that on-shore facilities, such as a fishermen’s institute and a library, were also needed. Once again he exhibited a talent for publicity and made regular contributions to the mission’s monthly journal, Toilers of the Deep … (London), where he dramatized the society’s spiritual and medical work. At this stage he was becoming knowledgeable not only about medical treatment at sea but also about advocacy, fishing, markets, and the toilers themselves. Unfortunately, his devotion to fieldwork led to neglect of his office duties, and in 1891 the mission’s council appointed a separate fund-raising secretary.

That year, at the request of the Newfoundland government, the council sent one of its members, Francis John Stephens Hopwood (later Lord Southborough), to investigate living and working conditions in the fishing industry. His findings dramatically changed the mission’s priorities. Hopwood was astounded by the deplorable living conditions in the migratory Labrador fishery, which was carried out by approximately 25,000 men, women, and children – Newfoundlanders who occupied temporary habitations with few essentials. In St John’s he suggested that the mission might send a hospital ship the following summer to provide basic medical care and distribute clothing. Back in London, he chose his words more carefully, presenting the expedition to Labrador as an “experiment.” In February 1892 the council decided to send Grenfell and the mission-ship Albert. Once it had been refitted for ice conditions, he got under way on 15 June.

Throughout the first summer, the Albert, flying the mission’s distinctive blue flag, visited many remote Labrador harbours, where Grenfell treated the full range of illnesses among the fishing population. At the same time he handed out clothing and religious tracts and held prayer meetings as far north as the Moravian mission station of Hopedale. As he proceeded, the enormous potential for Christian service took shape in his mind. He wrote to London to express his conviction that the experiment should become an annual feature – even a branch – of the mission’s work. By the time he arrived back in St John’s in October, he had seen over 900 patients, and no doubt remained about the direction his life would take. Moreover, the government of Newfoundland was prepared to erect and furnish two small hospitals and make a grant for their upkeep. Working through a local committee that included Samuel Blandford* and Augustus William Harvey*, the commercial interests of St John’s had pledged cash and houses for two hospitals if the mission provided the medical personnel.

Once the council had approved the venture, Grenfell returned to the Labrador coast with a medical staff for the summer of 1893, and hospitals were set up at Battle Harbour and Indian Harbour. On this voyage he piloted the steam-launch Princess May as far north as Nain, where he and his colleagues were greeted by the Moravian superintendent, Carl Albert Martin. Throughout the summer he encountered a population without adequate food, clothing, or medical treatment for several months of the year. Without consulting the mission, Grenfell then decided to take his annual leave to raise money in the larger Canadian cities. In Montreal he received a warm reception from such figures as Sir John William Dawson*, the recently retired principal of McGill University, and Sir Donald Alexander Smith*, who had worked in Labrador with the Hudson’s Bay Company. But by the time he returned to London in the spring, he had realized that the mission was not fully behind him since the costs were steadily rising. The Canadian government had also proved resistant, rejecting requests from the British Board of Trade and Grenfell for assistance in erecting a hospital on the north shore of the Gulf of St Lawrence. A group of Montreal supporters, including Smith and Thomas George Roddick*, nonetheless refitted the steam-yacht Sir Donald for Grenfell’s use.

During the winter of 1895, Grenfell finished his first book, Vikings of to-day; or, life and medical work among the fishermen of Labrador (London and New York), which established a pattern for other titles to follow. He walked a fine line between travel literature and promotion in order to bring Labrador before a general readership. Already he had moved past the requirements of a simple medical service and had embraced social problems that were beyond the reach of the Newfoundland government. Still not convinced, in 1896 the council ordered him to stay in England while it considered his future, but he went back to Newfoundland anyway. After leaving St John’s in the Sir Donald in June 1896, he called at Englee, on the Northern Peninsula, where he witnessed shocking hunger and deprivation, including a lack of fishing equipment. With a view to reforming the colony’s credit system, which always left the fishermen at a disadvantage, he experimented with a small cooperative store at Red Bay, Labrador.

While spending the next two seasons in the United Kingdom to oversee the mission’s initiatives, Grenfell persuaded a naval architect to draw up without charge plans for a steamer to be dedicated to the Labrador work. The plans called for a wooden-hulled vessel, but by the time construction started in 1898 it had become a steel-hulled hospital ship. The Strathcona, 97 feet overall, was launched in June 1899. Grenfell assumed he would take it to Labrador under his own command, but his Board of Trade certificate authorized him to sail nothing more than a yacht, so the council registered the vessel under the Merchant Shipping Act and brought over a qualified crew from Newfoundland to sail it back the following summer. Meanwhile, Grenfell was sent unexpectedly to Newfoundland in the fall of 1899 to replace one of his physicians. He then seized upon the idea of building a year-round hospital at St Anthony to treat the scattered population of Newfoundland’s French Shore. Thus, without any decision by the council, the mission in effect opened a branch on the Northern Peninsula; during the winter of 1899 Grenfell operated from the house of a local merchant. Once again, the mission was left to respond to the enthusiasms of its errant superintendent.

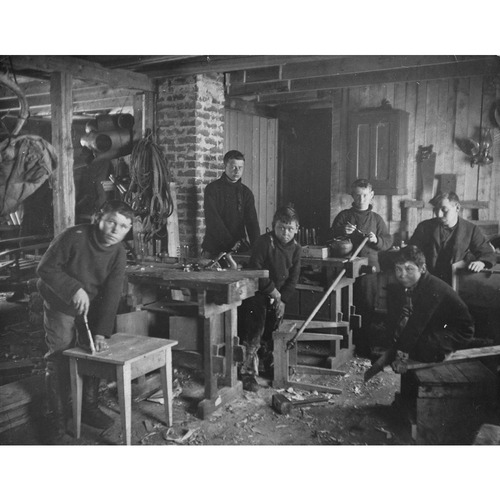

With expenses mounting, the mission insisted that greater assistance should come from North America. By so doing, it presented Grenfell with a platform for his own organization. He had made his first lecture tour of the United States in 1896. During his fund-raising trips through Canada and the eastern states in 1901 and 1902, he became more aware of the immense potential of American and Canadian philanthropy. In 1903 he met a useful ally, William Lyon Mackenzie King*, the deputy minister of labour in Ottawa, who opened doors to the Canadian bureaucracy. King also introduced him to the writer Norman McLean Duncan*, who would become one of his earliest promoters. Grenfell’s public lectures on Labrador created such interest, especially in New York, that he rapidly became idealized in the press as a saintly figure, a rugged individual intent on doing practical good works. The image was enlivened by Grenfell’s theatrical side and his boyish impulsiveness. Articles appeared in magazines aimed at Christian readers, and he was endorsed by Lyman Abbott, the influential Congregational clergyman who advanced in Outlook (New York) the rising reputation of Grenfell as a heroic, adventurous doctor. “If there is any better preaching of the Gospel of Christ in the world than this we do not know it,” he wrote in 1903. By then Grenfell had opened the hospital at St Anthony and started a fox farm and a sawmill there; he was also weighing the merits of an orphanage and more fishermen’s cooperatives. Inevitably, however, he was losing touch with the mission in London, which now considered handing over the whole enterprise to a joint Canadian-American committee before its financial resources were drained.

As a result of Grenfell’s advocacy, associations bearing his name had sprung up in Boston and Toronto. From 1903 a quarterly magazine, Among the Deep Sea Fishers (New York), published his articles and opinions as well as lists of donors. In 1905 The harvest of the sea … (New York), his second book on Labrador, came out and Norman Duncan produced Dr. Grenfell’s parish; the deep sea fishermen (New York), which together with Duncan’s journalism created a wider audience. A third association was founded in New York with a board of directors who placed a stamp of liberalism on Grenfell’s work, which was becoming less evangelical and leaning more towards the Social Gospel theology of the United States.

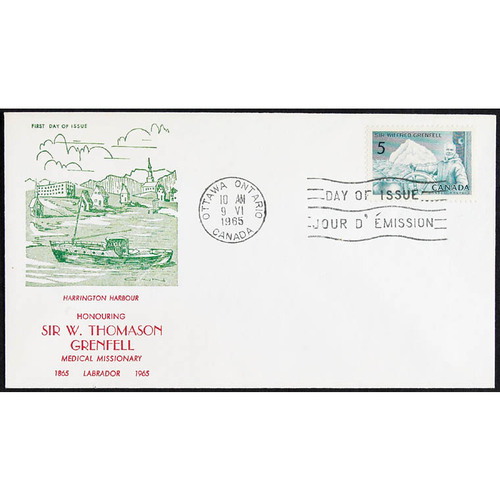

In the summer of 1905, with the assistance of King, Grenfell unsuccessfully approached the Canadian government for a grant to build a hospital at Harrington Harbour, Que., near the Labrador coast. He secured a gift for its construction from the daughters of Montreal brewer Andrew Dow while, in Ottawa, King succeeded in his push for an annual maintenance grant. To Harrington Harbour he sent Henry Mather Hare, a Halifax surgeon with missionary experience in China, and he presented the task of funding the hospital to the new Grenfell association in Montreal. The following year he persuaded Jessie Luther, a Rhode Island artist and occupational therapist who had worked at Hull House (a centre of social activism in Chicago), to teach crafts at St Anthony in order to develop an industry for local women. The arrival of Dr John Mason Little* in 1907 also enhanced the Grenfell mission’s medical reputation. An orphanage had been opened in 1906. As a result of these ventures, public accolades flowed, overwhelming the complaints of such seasoned missioners as Michael Francis Howley*, archbishop of St John’s. At the urging of King, Governor General Lord Grey* recommended Grenfell for the king’s birthday honours list, and in 1906 he duly became a cmg. The next year the University of Oxford made him an honorary doctor of medicine, the first such degree it had awarded.

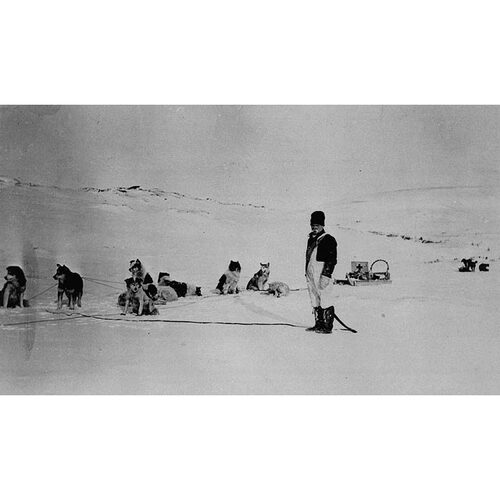

None of this recognition aided his cause more than his near-death experience in Hare Bay, south of St Anthony, on Easter Sunday 1908, when he went through the ice with his dogsled. He scrambled onto an ice pan with his dogs and was taken out to sea. Throughout the night, he avoided freezing to death by sacrificing three dogs for their skins. The next day he tried to attract attention by hoisting a makeshift flag on a pole contrived of their bones. Fortunately, he was rescued by local fishermen. This incident boosted his reputation to higher levels than ever, especially after sensational accounts appeared in British, Canadian, and American newspapers. His own celebrated narrative, Adrift on an ice-pan (Boston and New York, 1909), acquainted more readers, as well as potential donors, with his exploits.

In the winter of 1908–9, during another lecture trip in the United States, he was received as a hero. As he returned from England the following spring aboard the Mauretania, to accept honorary degrees from Harvard University and Williams College in Massachusetts, his life took a sudden shift when he met Anna MacClanahan of Lake Forest, Ill., and resolved to marry her. After putting in a summer on the Labrador coast, he journeyed to Chicago for their wedding in November at Grace Episcopal Church. (Though Grenfell would remain an Episcopalian, his religious outlook was ecumenical.) He went back to St Anthony with his bride in January 1910 to take up residence in a new house. Anne, as she spelled her name, installed herself as his private secretary, editor, and adviser, and it soon became clear that the pace of Grenfell’s life would not be as frantic. In 1910 she gave birth to Wilfred Thomason Jr, who would be followed two years later by Kinloch Pascoe and in 1917 by daughter Rosamond Loveday. Accordingly, with three children to raise, she spent most of each year at Swampscott, Mass.

Grenfell might have become domestic, but he did not slacken his efforts. The council in London soon learned of his latest initiatives, especially the expensive new seamen’s institute he was building in St John’s in 1910–11. The time seemed appropriate for it to withdraw from Newfoundland and Labrador. Consequently, in 1913, a new organization, the International Grenfell Association, was formed with branches in Britain, the United States, and Canada to oversee and regulate the corporate side of what had become known as the Grenfell Mission. Incorporated in January 1914, the IGA convened its first meeting at the Harvard Club of New York City.

Following the outbreak of World War I, Newfoundland began to experience financial hardship. The price of fish dropped considerably, and the costs of basic foodstuffs rose. At the same time, the Grenfell Mission’s expenses climbed and donations decreased. On the positive side, in 1915 Dr Henry Locke Paddon, Grenfell’s lieutenant in Labrador, opened a cottage hospital at North West River, and Dr Charles Samuel Curtis*, who would assume the management of the St Anthony hospital, appeared on the Labrador coast as a summer volunteer. That same year Grenfell, who wanted to go overseas, joined the Harvard Surgical Unit in support of the Royal Army Medical Corps, with the temporary rank of major. He arrived at the front in January 1916 and remained until late March.

In 1917, on the Newfoundland front, he weathered the most serious challenge to his legitimacy thus far, an inquiry headed by magistrate Robert T. Squarey. A group of merchants and traders had complained of the mission’s supposed competition in trade, its degrading representation of Newfoundlanders as paupers, and its reliance on American capital. Squarey exonerated the Grenfell association. Moreover, as the war drew to a close, Grenfell’s accomplishments in northern Newfoundland and Labrador continued to attract donors and volunteers. Once the conflict had ended, the time seemed propitious for Grenfell to put his story on paper and thereby supplement his dwindling personal income. With Anne’s help, A Labrador doctor … (Boston and New York, 1919), a Puritan-style spiritual autobiography with an emphasis on the Grenfell Mission and its role in hastening “the coming of Christ in Labrador,” appeared and became a commercial success. The mission’s labours certainly did not abate. At St Anthony a new brick orphanage was erected in 1922 and there were plans for a new hospital. The following year, throughout the field 24,731 patients were treated, 1,186 of them as inpatients.

Grenfell was doubtless riding a wave of celebrity, but he felt himself slowing down physically as he went about lecturing and raising funds. Although he could not have known it at the time, the source of his decline was probably the heart ailment since identified as Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome, which was transmitted to his daughter and granddaughter. As he approached his 60th birthday, he threw himself into the task of building an endowment fund for the IGA, and he continued to write, even though his condition and the demands of fame were tiring him out. The board of the IGA suggested a holiday. Accordingly, in June 1924 he left with Anne for a kind of sabbatical tour of the Near East and the Far East, during which the board moved ahead with further initiatives, fully demonstrating that it could act on its own. Chief among them was the new hospital at St Anthony, which incorporated the best medical technology. On 25 July 1927, as distinguished guests assembled for its official opening, Governor Sir William Lamond Allardyce announced that the king was making Grenfell a kcmg, an honour that required Anne Grenfell to give up her American citizenship.

Numerous public and professional honours followed, and in 1928 the students of the University of St Andrews in Scotland elected him lord rector, a largely ceremonial position he assumed in November 1929. In March of that year he had suffered a severe angina attack. He cancelled all his engagements and, with his wife, turned to the sanitarium run by Dr John Harvey Kellogg at Battle Creek, Mich. Still the mission’s nominal superintendent – he was back in St Anthony that summer – he relied all the more on Anne’s ability to manage the family’s affairs. His production of two more books, Forty years for Labrador (Boston and New York, 1932) and The romance of Labrador (New York and London, 1934), required her heavy involvement. Further attacks drained his energy, and he experienced pain doing practically everything except walking. On Anne’s initiative, they built a summer house on Lake Champlain in Vermont, where they would retire in 1935. He nonetheless remained committed to the mission and thought he could still influence affairs in Newfoundland. In 1934 he supported the formation of a government by commission [see Frederick Charles Alderdice] and was urged to consider the governorship. In January 1936 he finally wrote to the directors of the IGA to resign from the management of the mission’s work. His ankles were swollen and he suffered losses of memory. To make matters worse, Anne had developed a malignant tumour. They took up residence in a cottage on St Simons Island, Ga, where Grenfell endured one health episode after another.

Anne passed away in New York on 9 Dec. 1938, and Grenfell made a final trip to St Anthony the following summer to deposit her ashes in the rock face behind the hospital. He then divided his time between Georgia and Lake Champlain, where in October 1940, after playing croquet, he suffered his last attack and died.

Sir Wilfred Grenfell’s idealism and energy brought to the west and north coasts of Newfoundland, as well as to the south coast of Labrador, modern medical institutions and industrial and educational centres that raised the standard of living in those regions. Having carried them through the period of commission government, the Grenfell Mission was absorbed by the province following confederation in 1949. Meanwhile, the International Grenfell Association perpetuated itself to manage the funds raised by its founder over the years. Through the IGA and in countless testimonies Grenfell long continued to be held up as an example of beneficence. British travel writer Bruce Chatwin, for instance, confessed in an autobiographical essay that as a child in the 1940s he had three precious possessions, one of them The fishermen’s saint (London, 1930), Grenfell’s rectorial address at St Andrews. American novelist Saul Bellow also admired him: a character in his Henderson, the rain king (New York, 1959) tells us that “Forty years ago, when I read his books on the back porch, I swore I’d be a medical missionary.”

Mostyn House School (Parkgate, Cheshire, Eng.), Mostyn House papers. PANL, MG 63. Royal National Mission to Deep-Sea Fishermen (Fareham, Eng.), Council minutes; Finance committee minutes. Univ. of Oxford, Bodleian Library, Dept. of Special Coll. and Western MSS (Eng.), Francis John Stephens Hopwood, 1st Baron Southborough papers. Yale Univ. Library, MSS and Arch. (New Haven, Conn.), Wilfred Thomason Grenfell papers. Among the Deep Sea Fishers (New York, etc.), 1 (1903)–78 (1981). D. G. Halsted, Doctor in the nineties (London, 1959). Jessie Luther at the Grenfell Mission, ed. Ronald Rompkey (Montreal and Kingston, Ont., 2001). Labrador odyssey: the journal and photographs of Eliot Curwen on the second voyage of Wilfred Grenfell, 1893, ed. Ronald Rompkey (Montreal and Kingston, 1996). [H. L.] Paddon, The Labrador memoir of Dr Harry Paddon, 1912–1938, ed. Ronald Rompkey (Montreal and Kingston, 2003). Ronald Rompkey, Grenfell of Labrador: a biography (Toronto, 1991). Toilers of the Deep: A Record of Mission Work amongst Them (London), 1 (1886)–78 (1994).

Cite This Article

RONALD ROMPKEY, “GRENFELL, Sir WILFRED THOMASON,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 27, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/grenfell_wilfred_thomason_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/grenfell_wilfred_thomason_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | RONALD ROMPKEY |

| Title of Article: | GRENFELL, Sir WILFRED THOMASON |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2011 |

| Year of revision: | 2011 |

| Access Date: | February 27, 2026 |

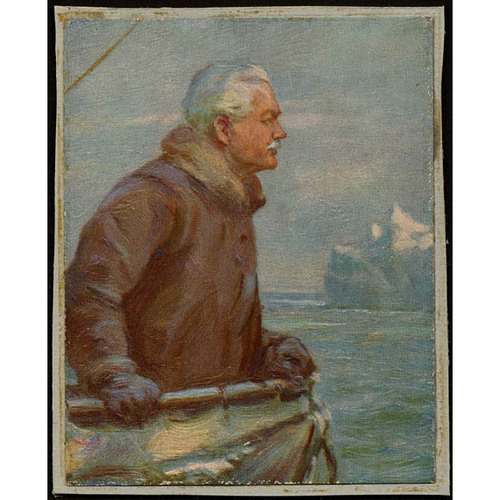

![[Sir Wilfred Grenfell aboard ship in the arctic] [graphic material]. Original title: [Sir Wilfred Grenfell aboard ship in the arctic] [graphic material].](/bioimages/w600.3362.jpg)