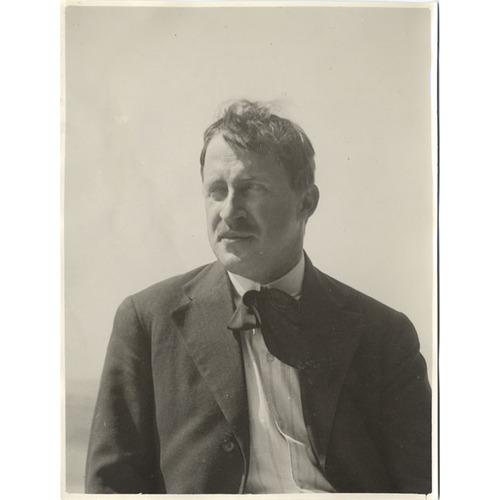

![Clarence Gagnon, [Vers 1925], BAnQ Québec, Collection Centre d'archives de Québec, (03Q,P1000,S4,D83,PG4), Photographe non identifié. Original title: Clarence Gagnon, [Vers 1925], BAnQ Québec, Collection Centre d'archives de Québec, (03Q,P1000,S4,D83,PG4), Photographe non identifié.](/bioimages/w600.25064.jpg)

Source: Link

GAGNON, CLARENCE (baptized Clarence-Alphonse, he often signed Clarence-A. Gagnon), painter, engraver, designer, and illustrator; b. 11 Nov. 1881 in the parish of Saint-Jacques, Montreal, son of Alphonse-Edmond Gagnon, a merchant, and Sarah Ann Willford; m. first 2 Dec. 1907 Katherine Irwin (d. 14 April 1919 of Spanish influenza) in Paris; m. secondly 10 June 1919 Lucile Rodier in the parish of Saint-Léon-Premier, Westmount, Que.; no children were born of either marriage; d. 5 Jan. 1942 in Montreal and was buried there three days later in Notre-Dame-des-Neiges cemetery.

Success

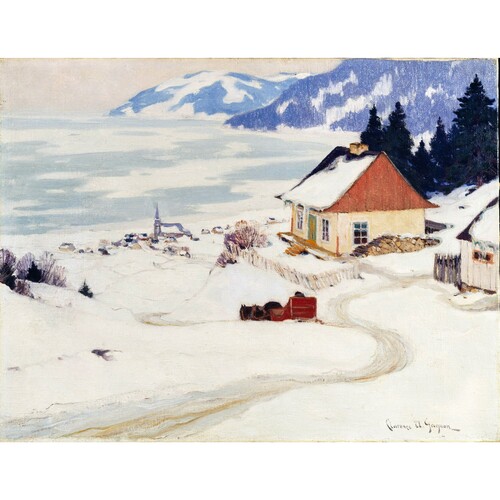

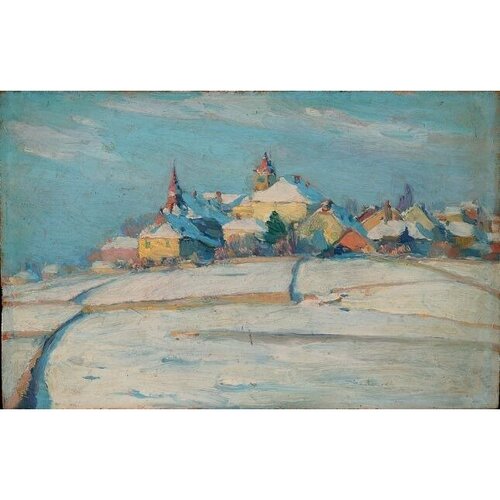

“I am constantly immersed in my memories of Baie-Saint-Paul, I would even say the happiest of my life, for the days I passed there will carry over into my works an impression that I hope will live on long after the worms have cleaned up what is left of me.” When Clarence Gagnon wrote these words to his close friend, Dr Euloge Tremblay, on 8 Nov. 1931, it was a few days before his 50th birthday, and since the beginning of the century in Paris, he had been enjoying a career that shone brightly in London, New York, Montreal, and Toronto. Evolving as an artist in the City of Light during the revolutionary period of avant-garde artistic movements, the Canadian owed his success to scenes inspired by rural villages nestled in the snow of the Charlevoix mountains. In the capital of the arts, his work represented sought-after Nordic exoticism, certainly, but in the era of industrialization and modernization, it also represented vestiges of another age.

Childhood, family, and education

The fifth in a family of nine children, Gagnon enjoyed a comfortable childhood in Montreal and Sainte-Rose (Laval), a municipality on Île Jésus on the banks of the Rivière des Mille Îles. His father, businessman Alphonse-Edmond, played a part in turning Sainte-Rose and its surroundings into a resort area that was popular with rich Montreal anglophones in summer. Artists such as the sculptor Louis-Philippe Hébert* and his family settled there, as did as the painter and caricaturist Henri Julien*, with whom Clarence would go fishing, a pastime that, like hunting, he fervently pursued all his life. The childhood deaths of two brothers and two sisters cast a shadow over his idyllic early years, which were again darkened by the loss of his mother, Sarah Ann, before he reached his tenth birthday. She had provided him with an education in the language of Shakespeare, and he was as proficient in English as he was in French.

When he was old enough, Clarence entered the little school in Sainte-Rose. He then followed in the footsteps of his brother Willford-Arthur, who later became a renowned architect and with whom he formed a lasting fraternal and professional relationship. He trained at the Académie du Plateau, the oldest lay educational institution for boys in Montreal [see Urgel-Eugène Archambeault*], probably starting in 1892. The painter Ludger Larose, a former pupil of Jean-Paul Laurens and Gustave Moreau in Paris, introduced him to drawing. Completing his studies in June 1898, Gagnon was honoured with a special commendation, an award of excellence, and a bronze medal for his achievements in the English language. He refused to embark on the business career planned for him by his father, and despite being deprived of financial resources, the graduate was determined to become an artist. He enrolled in free evening classes at the Council of Arts and Manufactures of the Province of Quebec, housed in the Monument National, Rue Saint-Laurent. In 1898–99 he was among the first cohort of students to experience the new French academic orientation injected into the art classes led by Edmond Dyonnet; until then they had been based on the British model. Around 1899 Gagnon continued similar training at the school of the Art Association of Montreal (AAM), where he pursued his apprenticeships until 1903 thanks to financial help from an aunt. William Brymner*, known as a good teacher and listener, provided rigorous instruction that was based on studying plaster casts and live subjects, copying the works of the masters in museums, and painting outdoors. Gagnon appreciated the relationship of trust that Brymner established with his pupils; he urged them to be attentive to the expressiveness of a motif and to give free rein to their individual vision, allowing them to explore innovations in form. While a student, Gagnon also took advantage of the exhibitions and lectures given at the vibrant AAM; he was captivated by Japanese art, whose refinement soon pervaded his work. In January 1900 he also had a decisive encounter with the painter Horatio Walker*, whom the art historian David Karel would describe as the “herald of Île d’Orléans”; his canvases, which perpetuated the spirit of the Barbizon School in his depictions of landscapes inspired by rural settings, the animal world, and nature, were prized on the New York market.

Sojourns on the Côte-de-Beaupré and in Charlevoix

During the summer of 1900 Gagnon travelled to Sainte-Pétronille on Île d’Orléans to visit Walker. He painted outdoors on the Côte-de-Beaupré, just as a group of artists – his teachers Dyonnet and Brymner, along with Maurice Galbraith Cullen*, James Wilson Morrice*, and Edmund Montague Morris* – had been doing since 1896. Coming from Montreal and Toronto in summer and winter, the artists of “Beaupré’s little band,” as the art historian Madeleine Landry would call them, sought the authentic, original character of the countryside, the traces of which were disappearing from large towns because of modernization. Yet such traces were still palpable in Quebec City and more so in the rustic villages strung out along the narrow ribbon of land on the north shore of the St Lawrence, which resembled those of France in an earlier era. Two more stays (in 1901 and 1902) followed. During these excursions, Gagnon travelled as far as Baie-Saint-Paul in the Charlevoix region, returning with pochades (quick sketches) and landscapes, which he exhibited in Montreal at the annual exhibitions of the AAM and the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts. His scenes of country life – flocks of sheep, women tending geese, tillers at work – and his landscapes caught the attention of art lover and dealer James Morgan of the retail enterprise Henry Morgan and Company [see Henry Morgan*]. In December 1903 Gagnon signed a contract with him that financed his first trip to France. For Ploughing with oxen (1903), one of the paintings entrusted to Morgan, Gagnon won a bronze medal at the Louisiana Purchase exposition in St Louis, Mo., in 1904. The association between Gagnon and Morgan would end a little over five years later.

Travels in Europe

On 9 Jan. 1904 Gagnon, aged 22, boarded a ship at Saint John bound for Liverpool, England. In his luggage he carried a few pochades and some materials for engraving, an art form he had begun to practise on Brymner’s advice. At the New Gallery in London he viewed the exhibition of the International Society of Sculptors, Painters and Gravers, whose renowned president, James Abbott McNeill Whistler, had died just six months earlier. Gagnon was deeply impressed by Whistler’s engravings, and also sensitive to his novel manner of exhibiting works, integrating all spatial elements and hanging paintings, drawings, and studies in no particular order. Among the painters of many nationalities whose works were on show at the New Gallery, Gagnon found his fellow Canadian Morrice, whose scenes of Paris and Breton beaches were being displayed. A few months later, at the end of his visits to the Parisian salons, Gagnon concluded that only Whistler and Morrice had not disappointed him.

In February 1904, having settled in Paris’s Montparnasse quarter along with Montreal artists Edward Finlay Boyd, William Henry Clapp, and Henri Hébert, Gagnon lost no time in enrolling at the Académie Julian, where he frequented the studio of Jean-Paul Laurens until April 1905. His nomadic temperament soon gained the upper hand: upon completing his study sessions, he embarked on travels in Spain and Morocco, with frequent trips to Brittany and Normandy in France and to Rome and Venice in Italy. He absorbed the Venetian masters, who, he wrote to Morgan, “will give you far better lessons than the old traditional academic training that a student gets in the school today, which is only good to stifle what little individuality you possess.”

An exuberant bohemian, an excellent conversationalist, curious by nature, vigorous, and a perfectionist, this energetic man openly embraced people and events during his wanderings. His was an independent, persevering, even obstinate spirit. Thanks to his engaging personality and first marriage into an affluent circle of Montreal society, he was able to lead a bohemian life in Paris and make a living from his art by skilfully surrounding himself with competent dealers in Europe and Canada.

Engraver

Americans formed the largest contingent of foreign students in Paris, a fact that had justified the creation in 1890 of the American Art Association of Paris (AAAP). Gagnon joined the group in 1904 and began to learn etching with Donald Shaw MacLaughlan, an American engraver who had been born in Canada. Gagnon’s participation in two 1906 exhibitions, one at the Salon de la Société des Artistes Français and the other at the AAAP, drew attention. He received an honourable mention for the first and this appraisal for the second: “Among these new practitioners of etching, the most gifted and most profoundly artistic seems, for the moment, to be Mr Clarence Gagnon.” These words from the influential Roger Marx, published in the March issue of the Paris Gazette des beaux-arts, launched his career as an engraver. In his article “Une exposition d’aquafortistes américains,” which he chose to illustrate with Gagnon’s View of Rouen (1905), the critic praised the refinement of his rapid impressions and his constant concern with composition. The movement to revive original etching, which had been flourishing in France since the second half of the 19th century, found in Gagnon an illustrious Canadian representative. His success can be measured by some 30 occasions when he participated in exhibitions of prints then circulating in Europe and North America, as well as by the keen interest of the most prestigious private and public collectors.

Gagnon would return from his many travels with plans for engravings; he made especially good use of postcard images to refresh his memory. He executed and printed his works at 9 Rue Falguière, where he had established his studio in December 1907; he would retain it until his final departure from Paris in 1936 (over the course of his career he sojourned in France five times). Intricately engraved views of Venice, picturesque depictions of old streets in Brittany and Normandy, and scenes of Picardy with dramatic effects were all compositions that aroused the keen interest of large museums, especially the South Kensington Museum in London in 1906 and the Library of Congress in Washington in 1908 (Rue des Cordeliers, Dinan, Paris, 1907–8). Reverberations of his success stimulated the market for prints in Canada, especially in Montreal, where his work prospered throughout the 20th century. Following his meteoric rise to fame, the artist lost interest in ink and the steel nib. In a letter (23 Feb. 1908) to the merchant Frederick Cleveland Morgan*, son of James, he explained: “I prefer being known as a painter [rather] than an etcher and naturally would like to be well known in Canada where I shall probably live someday.” Gagnon did his final work on copperplate, Jardins du grand séminaire, Montréal (Montreal) in 1917. Nevertheless, to meet demand in the North American market, he continued to make prints from old plates until 1925.

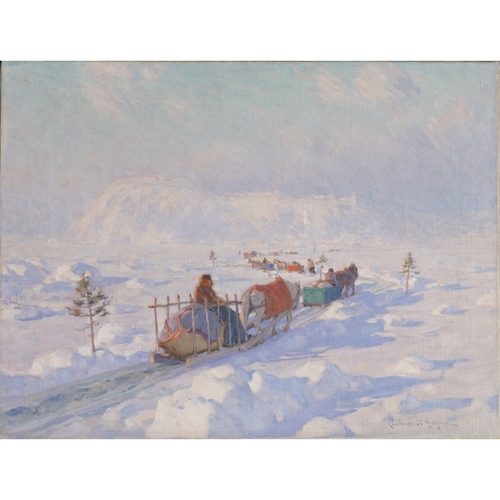

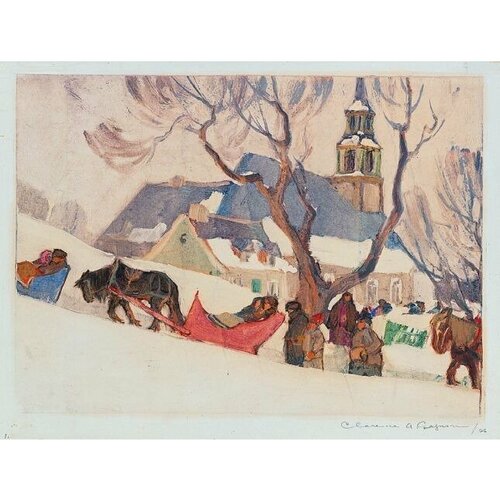

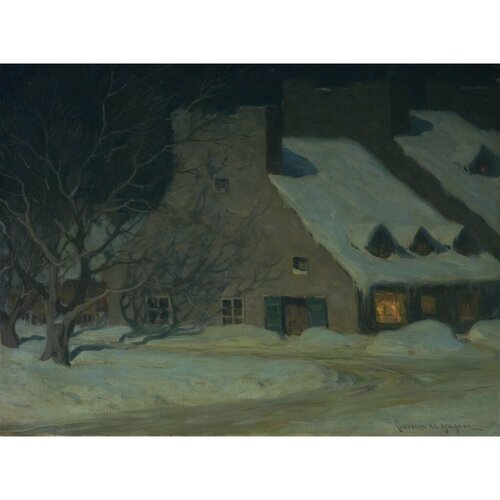

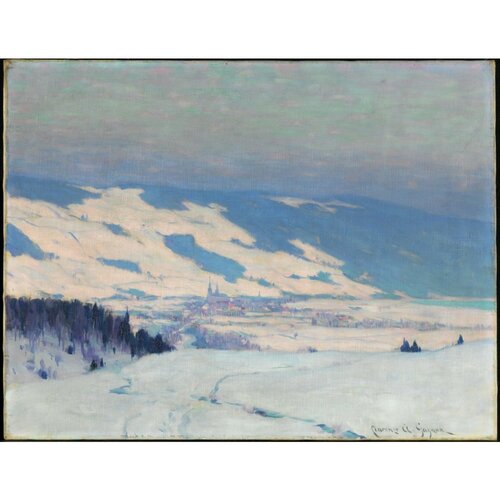

Pictorial output: style and principles

After arriving in Paris, Gagnon largely favoured European subjects in his painting, as was the case with his engraving, although his pictorial output differed in that its range was more varied, including, as it did, portraits of farmers and scenes of Breton beaches. On the sands, Dinard (Dinard, France, 1907) speaks to his interest in Impressionism, whose techniques could be used to render the atmosphere and luminosity inherent in the subject of northern beaches, then a very popular theme in the salons. It is notable that the painter’s palette had become lighter during his time in France, and when he first returned to Canada, staying there from July 1908 to December 1909, Gagnon assessed the expressive power that pure, bright colours infused into depictions of the Laurentian countryside, which were exceptionally attractive when they evoked winter. He was well aware of the Parisian success of Impressionist compositions enlivened by the changing effects of light on snow or ice, as created by his predecessors Cullen, Morrice, and Marc-Aurèle de Foy Suzor-Coté*. Sensitive for a period to the fleeting impressions of light on snow, Gagnon soon translated the effects of winter “by contradictory sensations of warm light blazing on snow-covered ground,” as the critic Léon de Saint-Valéry marvelled in the Paris Revue des beaux-arts (May 1912) when writing on the subject of Paysage d’hiver au Canada, a work shown at the Salon of the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts. On the one hand, Gagnon’s painting evolved from capturing atmospheric effects towards Synthetism, which demonstrated his familiarity with Paul Gauguin’s work. It also moved towards a decorative stability that emphasized the interplay of arabesques and snaking lines on smooth surfaces while contrasting warm and cool colours (The wayside cross, Quebec,1916 or 1917). On the other hand, his art extolled the value of a strong identity that was in keeping with the wave of regionalism in Canada; as in the United States and Europe, it glorified the traditional life of rural communities, which were threatened with dissolution by the Industrial Revolution and urbanization. His only solo exhibition during his lifetime – the first of such importance for a Quebec artist in Paris – crystallized his principles. Held in 1913, from 27 November to 16 December, at the Galerie A. M. Reitlinger in the 8th arrondissement, the show, “Paysages d’hiver dans les montagnes des Laurentides au Canada,” brought together 75 paintings and studies in oil, most of which did in fact deal with winter in Canada. In the wake of the presentations instigated by Whistler at the end of the 19th century, the many visitors could enjoy a global aesthetic experience expressed, for example, in the handmade frames of Gagnon’s paintings, which were decorated by the artist with motifs of animals reminiscent of the Charlevoix region.

This aspect of his work arose from the arts and crafts movement and became an overriding preoccupation for the artist. Preserving artisan traditions was something he championed on several fronts. Having returned to Canada after the First World War, Gagnon, a man of action, settled in Charlevoix (1919–24) and partnered with rural artisans, for whom he designed cartoons for hooked rugs and patterns for ceintures fléchées. He oversaw the distribution of their products through the Canadian Handicrafts Guild of Montreal and the Toronto section of the Women’s Art Association of Canada. It was also during this period that he decided to grind his own pigments and develop his own colours, efforts that culminated in receiving the William Trevor Prize of New York’s Salmagundi Club, which he won in 1923 for his painting Winter morning, Quebec (1922).

National and international activities

During the 1920s Gagnon increased his national and international activities. He continued making progress as a painter and proved to be a skilful emissary of Canadian artwork abroad. Elected to the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts in 1921, Gagnon chose The pond, October (1921) for his diploma piece. He was invited to exhibit and take part in preparing the Canadian presentations for the British Empire Exhibition of 1924 and 1925, which was held at Wembley (London) and sponsored by Ottawa’s National Gallery of Canada. The well-organized Gagnon also gave valuable support to the 1927 “Exposition d’art canadien” at the Musée du Jeu de Paume in Paris. The National Gallery of Canada and Toronto’s Art Gallery of Ontario subsequently hastened to acquire two of his exhibited paintings, Village in the Laurentian Mountains (1925) and Horse races in winter (1927), respectively, which were representative of the decorative character that dominated his mature period.

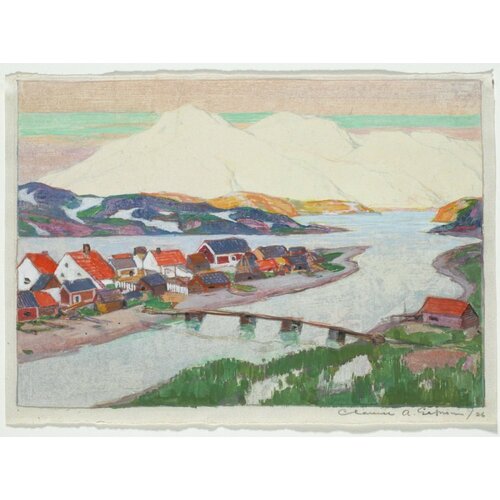

In 1925 Gagnon began his final sojourn in France; it would be the longest, lasting more than ten years. Punctuated by numerous travels in Scandinavia and other parts of Europe, this period provided opportunities for experimentation with new art forms, this time in the field of illustration. In 1925 and 1926 he supplied original motifs for Christmas cards for the Canadian Artists Series of the firm Rous and Mann Limited in Toronto. Having gained experience working in small formats when producing pochades and prints, he excelled in capturing a region’s evocative power in delicate illuminations destined to be reproduced in the thousands without impairing the exquisite subtlety of his colours. In 1925 he had become interested in monotype with a view to illustrating books commissioned by Éditions Mornay in Paris: Le grand silence blanc (roman vécu d’Alaska) by Louis-Frédéric Rouquette, published in 1928, and Maria Chapdelaine by Louis Hémon*, published in 1933. His perfectionist temperament was sorely tried during the five years (1928–33) it took to produce the 54 illustrations (La récolte, for example) for Maria Chapdelaine, which met with immediate success in France and Canada. Gagnon would paint almost nothing more after 1933.

Final years

In 1936 Gagnon returned to Canada to settle permanently, although he retained his studio in Paris. He divided his time between Westmount and Baie-Saint-Paul. At age 55 his career in Europe had lasted some 20 years – longer than in his own country. He was received in Montreal with the homage due his reputation and his renown as an illustrator, as evidenced by the reception given in his honour by the Arts Club of Montreal on 6 December. In 1938 the Université de Montréal awarded him an honorary doctorate.

Passionate about the revival of domestic and rural arts and the protection of French Canada’s heritage – interests he shared with the ethnologist Marius Barbeau* and the director of the École du Meuble in Montreal, Jean-Marie Gauvreau* – and inspired by models he had observed in Norway and Sweden, Gagnon became involved in creating a museum of folklore for Île d’Orléans in 1938 and for Mount Royal in Montreal the following year. These projects, which he fought for with an energy born of despair, never saw the light of day. In Montreal, times had changed. An uneasy witness to the rise of the progressive forces of contemporary art, especially with the founding of the Contemporary Arts Society of Montreal, Gagnon led a virulent assault against any innovation in form, giving a speech at the Pen and Pencil Club titled “The grand bluff of Modernist art.”

Beginning in June 1941, Clarence Gagnon was weakened by illness, and he died six months later, aged 60, of pancreatic cancer. In 1942 a vast retrospective prepared and presented by the Musée de la Province in Quebec City, and then by three other Canadian museums (the AAM, the Art Gallery of Toronto, and the National Gallery of Canada), paid tribute to the artist whose landscapes, imbued with Edenic characteristics of rural Quebec, had been distinctive on the national and international art scenes. A man of action and organization, Gagnon had served his country well by promoting Canadian art beyond its borders.

In 1965 Lucile Rodier, Clarence Gagnon’s widow, bequeathed to Montreal’s McCord National Museum the artist’s extensive correspondence with many people, including his brother Willford-Arthur, Canadian friends such as Euloge Tremblay, and Montreal business contacts, including Frederick Cleveland Morgan. This material is now held in the Clarence A. Gagnon fonds (P116).

The original English version of Gagnon’s 1939 speech at the Pen and Pencil Club, “The grand bluff of Modernist art,” can be found in the Jean-Marie Gauvreau fonds (MSS2) at the Centre d’arch. de Montréal, Bibliothèque and Arch. Nationales du Québec. The French translation was published in four articles in Amérique française (Montréal), 7 (1948–49): “L’immense blague de l’art moderniste,” no.1: 60–65, “L’immense blague de l’art moderniste: deuxième partie,” no.2: 44–48, “L’immense blague de l’art moderniste (suite),” no.3: 67–71, and “L’immense blague de l’art moderniste (suite et conclusion),” no.4: 30–33.

The record of Gagnon’s first marriage could not be located. Details of the event are included in an article published on 30 Dec. 1907 in Le Canada (Montréal) and in a letter to his art dealer, James Morgan, written on 28 Aug. 1907 and preserved in the Clarence A. Gagnon fonds.

Gagnon’s paintings, engravings, illustrations, and handicrafts number in the hundreds, of which pochades (small oil sketches) make up the majority. Even though his paintings are held by Canada’s most prominent museums from coast to coast, other works can be found in private collections. Most of his engravings (46 prints) are held by the National Gallery of Can. (Ottawa) and the Musée National des Beaux-Arts du Québec (Québec); and the 54 coloured illustrations for Louis Hémon’s novel Maria Chapdelaine (Paris, 1933) are preserved in the McMichael Canadian Art Coll. (Kleinburg, Ont.).

For more information on Gagnon and his works, see the monograph by Hélène Sicotte, Clarence Gagnon, 1881–1942: dreaming the landscape, trans. Judith Terry and Donald Pistolesi (Montreal, 2006), in the exhibition catalogue of the Musée National des Beaux-Arts du Québec, which also includes the author’s essay on the painter-engraver and the catalogue raisonné of his engravings (the latter created in collaboration of R. L. Tovell). Background information on the exhibition is contained in Musée National des Beaux-Arts du Québec, ser.: exhibitions, file: Clarence Gagnon: rêver le paysage, as well as the museum’s René Boissay collection of documents; they are indispensable resources for research carried out in recent decades. Also of interest are the following works: René Boissay, Clarence Gagnon, trans. Raymond Chamberlain (Ottawa, 1988); F.-M. Gagnon and Andrée Gendreau, Clarence Gagnon, 1881–1942 (exhibition catalogue, Centre d’exposition de Baie-Saint-Paul, Québec, s.l., [1992]); Galerie A. M. Reitlinger, Exposition Clarence A. Gagnon … ([Paris, 1913]), and Les peintres de neige: exposition internationale (Paris, 1914); J.-M. Gauvreau, “Clarence Gagnon, r.c.a., ll.d., 1881–1942”, Technique: Industrial Rev. (Montreal), 18 (1943): 435–42, 458–68; Hughes de Jouvancourt, Clarence Gagnon (Montréal, [1970]); A. H. Robson, Clarence A. Gagnon, r.c.a., ll.d. (Toronto, 1938); and I. M. Thom, “Maria Chapdelaine”: illustrations (exhibition catalogue, McMichael Canadian Art Coll., Kleinburg, 1987).

For the artistic context of the period, see also: David Karel, André Biéler at the crossroads of Canadian painting ([Quebec], 2004); Madeleine Landry, Beaupré, 1896–1904: lieu d’inspiration d’une peinture identitaire (Québec, 2014); J.-R. Ostiguy, Les esthétiques modernes au Québec de 1916 à 1946 (exhibition catalogue, National Gallery of Can., Ottawa, 1982); Le Groupe des Sept: la collection du Musée des beaux-arts du Canada; le paysage au Québec, 1910–1930 (exhibition catalogue, Musée du Québec, Québec, 1997); and R. L. Tovell, A new class of art: the artist’s print in Canadian art, 1877–1920 (exhibition catalogue, National Gallery of Can., Ottawa, 1996).

Ancestry.com, “Quebec, Canada, vital and church records (Drouin coll.), 1621–1968,” Basilique Notre-Dame (Montréal), 17 avril 1919; Saint-Léon (Westmount, Québec), 10 juin 1919: www.ancestry.ca/search/collections/1091 (consulted 2 Sept. 2022). Bibliothèque et Arch. Nationales du Québec, Centre d’arch. de Montréal, CE601-S33, 12 nov. 1881. La Presse (Montréal), 7 janv. 1942. David Karel, Horatio Walker (exhibition catalogue, Musée du Québec, [Québec], 1986).

Cite This Article

Michèle Grandbois, “GAGNON, CLARENCE (baptized Clarence-Alphonse) (Clarence-A. Gagnon),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 17, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 21, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/gagnon_clarence_17E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/gagnon_clarence_17E.html |

| Author of Article: | Michèle Grandbois |

| Title of Article: | GAGNON, CLARENCE (baptized Clarence-Alphonse) (Clarence-A. Gagnon) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 17 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2025 |

| Year of revision: | 2025 |

| Access Date: | February 21, 2026 |