Source: Link

Gascoigne, MARGARET, educator, school administrator, and musician; b. 3 Aug. 1876 in Nottingham, England, daughter of Thomas Gascoigne, a hosiery manufacturer, and Rebekah Houghton; d. unmarried 16 Nov. 1934 in Montreal and was buried in Mount Royal Cemetery in Outremont (Montreal).

Education

Margaret Gascoigne exemplifies the autonomous “new woman” who emerged during the late 19th century in Europe, the United States, and Canada [see Isabel Ecclestone MacPherson*; Margaret Townsend*]. Recently liberated by an educational revolution that freed them from finishing schools, where they were prepared solely for marriage and motherhood, these women took their studies and careers seriously. Gascoigne’s education, however, also underlines some of the limitations of this revolution. Despite the new educational opportunities, she chafed against her early schooling in Nottingham, which, she would write in her unpublished memoirs, consisted of “the poorest teachers imaginable” and a curriculum forcing students to cram for Oxford local examinations. From an early age she vowed to open her own institution to teach “things that really mattered.”

The education Gascoigne decried nonetheless provided her with a solid foundation and the ability to make concrete choices about her future. Torn between attending the University of Oxford or studying music in Germany, she chose to enter Oxford’s Lady Margaret Hall in 1894. There she distinguished herself as an “extraordinarily teachable young woman,” according to her tutor Annie Maude Stella, who would eventually become vice-principal of Lady Margaret Hall. Although Gascoigne completed her studies in classical moderations with honours in 1898, she did not receive a degree; Oxford would not grant degrees to women for another 22 years.

Early teaching career

Many Oxford alumnae of Gascoigne’s generation would become well known in national and international circles as scholars, educators, writers, and social activists, notably for the cause of women’s suffrage [see Ethel Hurlbatt; Eliza Ritchie]. Gascoigne, who was never involved in the suffragist movement in either England or Canada, turned to teaching and the pursuit of her dream to open her own school. Although private schools for girls were expanding and flourishing, success proved elusive as she drifted from one position to the next: as a governess for various families, as a second mistress at Howell’s School in Denbigh, Wales, and as a teacher at St Margaret’s School for orphans in Bushey, Hertfordshire. Refusing to be bound by circumstances, Gascoigne joined the wave of British immigrants who left for Canada before the First World War. In 1913 she arrived in Montreal to teach at Miss Edgar’s and Miss Cramp’s School, settling in the Square Mile, the heart of the city’s wealthy English-speaking population.

As was the case during her post-Oxford years, Gascoigne’s early days in Montreal proved to be a struggle. True to her ambition, in 1914 – less than a year after starting her job – she printed a prospectus to advertise the opening of a school for girls “of the age of 7 and upwards,” but nothing materialized. By 1915 Gascoigne had applied for and been refused a position as principal at the Trafalgar Institute (renamed the Trafalgar School for Girls in 1934) and she resigned from her post at Miss Edgar’s and Miss Cramp’s School. Determined to remain in Canada, she borrowed 20 dollars, rented a room in the Grosvenor Apartments on Sherbrooke Street, and took on private pupils there. She even applied, without success, for a teaching job in western Canada, and for a time she returned to working as a governess.

The Study

Gascoigne would soon experience and benefit from changing times. As in England, by the end of the 19th century, Canadian universities had gradually begun to allow women to enrol. In 1884 Lord Strathcona [Smith*] endowed the first two years of separate classes for women at Montreal’s McGill College, which became a university in 1885. By 1898 he had financed the creation of a women’s college at McGill, the Royal Victoria College [see Hurlbatt], which formally opened in 1900. Slowly but surely, middle-class girls were being educated to take their high-school exams with university as their goal. The times were favourable for other reasons. The first two decades of the 20th century witnessed unprecedented population growth. To meet the demands of a prosperous and essentially British segment of Montreal, private schools were being set up, and Gascoigne found a niche. Her Oxford credentials, charismatic personality, and business acumen quickly attracted important connections that enabled her to establish a school for girls in 1915 amid competition from existing English-language private institutions. Called The Study, it operated in a room on Drummond Street. The institution had humble peripatetic beginnings, moving to various locations in the Square Mile, but Gascoigne’s purchase of a house on Seaforth Avenue in 1922, followed by The Study’s incorporation that year, signalled the remarkably rapid success of her enterprise. Indeed, Gascoigne’s generous employment conditions in 1922 reflected the optimism surrounding her school. Under the terms of incorporation, she was to receive an annual salary of $2,500 with predetermined increases, a pension upon retirement, and free room and board in the school building.

The board’s optimism would not prove to be misplaced. Throughout the 1920s The Study grew steadily, and by 1926 it was turning a profit. Having opened in 1915 with 6 pupils and Gascoigne as the only teacher, by the 1928–29 school year the institution had 216 pupils and 17 teachers. Such healthy growth meant that it did not have to dramatically increase its fees over the decade. In 1920, for example, second-, third-, and fourth-form students were paying $170 to attend, while fifth- and sixth-form pupils were charged $225. By 1925 tuition had increased to $200 for lower school, $225 for middle school, and $250 for upper school, and those fees would remain stable until the end of the decade.

By the 1920s many Study graduates were moving on to universities such as McGill and the University of Toronto, and even abroad to Oxford, Bedford College at the University of London, and the Sorbonne in Paris. The Study had become known as a place of high achievement, a distinction it has retained in the 21st century. Distinguished alumnae from Gascoigne’s time include painter Marian Scott [Dale*]; museum curator Isabel Marian Barclay* (Dobell); and Dorothy Osborne (Xanthaky), who would study physics under Lord Rutherford and would become a senior member of the Canadian Department of External Affairs after the Second World War.

Margaret Gascoigne was a woman of considerable vision and flexibility. Without question, girls’ education was a passion, but she was not unwilling to compromise in the greater interests of the institution, financial or otherwise. Over the years, boys – beginning with Esmond Peck, who appears in a school photograph of the 1917/1918 class – appeared sporadically on The Study register until they were definitively excluded in the early 1980s, when Eve Marshall was headmistress. Even though Gascoigne spent much of her time among the elite English-speaking community of Montreal’s Square Mile, she also operated beyond it. She was a member of the Association of Headmistresses of Canada and was elected its treasurer in 1932. In spite of her predominantly English associations, Gascoigne recognized the importance of French culture in Quebec. From 1916 onwards, with the hiring of Marcelle-Jeanne Boucher, French became an integral part of The Study’s curriculum. In 1920 Gascoigne wrote the piano accompaniments for Chansons of old French Canada (Quebec City, 1920), a collection of folk songs with illustrations by Ethel Seath*, script by James Kennedy, and a preface by Canadian ethnologist Marius Barbeau*. In fact, Gascoigne’s association with Seath – a friend, colleague, Study art teacher, professional painter, founding member of the Beaver Hall Group (also known as the Beaver Hall Hill Group) in 1920, and a member of the Canadian Group of Painters in 1939 – remains an enduring testimony to The Study’s cultural and social links with the national art world of the day.

Although The Study retained many features of British private schools, such as uniforms and the prefect system, its underlying principles were not traditional; rather, they were rooted in some of the most radical educational philosophies of the day, as espoused by British essayists and scholars Kenneth Richmond and Arthur Clutton-Brock. For example, Gascoigne believed that music, art, and poetry should be studied not as accomplishments for refined young ladies but as integral aspects of an educational vision based on the love of and search for “goodness, truth and beauty.” Students did not receive grades or academic prizes; nor did they write formal examinations. This approach did not, however, preclude the purchase of scientific apparatus for the teaching of physics, and it did not lose sight of the practical realities of preparing young girls for matriculation exams and careers. Gascoigne brought the world to The Study. Over the years the school welcomed guest musicians, artists, actors, and speakers who enriched the curriculum with an array of concerts, recitals, plays, magic-lantern shows, and lectures. Gascoigne had trained as a classical pianist, and she used her skills to enhance traditional classroom teaching. Sometimes music dominated the entire morning. The children would sit on the floor while Miss Gascoigne played Beethoven, Chopin, Liszt, or a piece of their choosing.

Final years and legacy

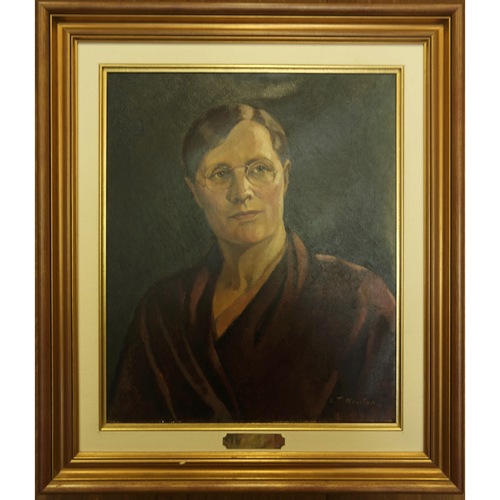

With the advent of the Great Depression, Gascoigne’s enterprise faced the serious challenges of student withdrawals and the inability of some parents to pay. As the board grappled with the financial crisis and the need to maintain enrolment, thousands of dollars of unpaid fees accumulated. Confronted with a growing deficit, the board cut staff salaries and asked bondholders to temporarily defer payment of interest. The bank even reduced its interest rate on the mortgage. By 1933, in addition to accepting a significant salary cut, Gascoigne had given up the apartment guaranteed in her 1925 contract and moved back into the school. At the same time her health was failing. In January 1934 she underwent major surgery for breast cancer. She never officially resumed her duties and succumbed to the disease on 16 Nov. 1934. Her funeral service was held at Montreal’s Anglican Christ Church Cathedral, where The Study’s closing ceremonies had taken place since 1926. In the school newsletter a few months earlier, Gascoigne’s students described her as “the greatest influence for the good that we have had in our lives.” To honour her memory, some families of The Study’s students and its Old Girls’ Association commissioned Lilias Newton [Torrance*] to paint Gascoigne’s portrait, which still hangs in the school’s vestibule.

Although Gascoigne’s death was an enormous blow to The Study community, the $20,000 life-insurance policy she left to the school helped mitigate its financial crisis. The donation reduced the mortgage and made funds available to keep the institution going for the next two or three years. By 1936 the board was experiencing a general economic recovery and was able to place The Study on a firm financial footing by scaling down the bond issue and gradually reducing debt. By 1944 The Study was virtually debt-free.

In an atmosphere of privilege, Gascoigne drew attention to suffering, affirming the human ability to, as she wrote in the school’s newsletter, “create an atmosphere of peace and love,” without thought of “jealousy or greed or self-seeking,” to bequeath a “nobler and better heritage” to the next generation. She was ever cognizant of the underprivileged. In her will she requested that in lieu of flowers at her funeral, contributions be made towards a fund to help children who would otherwise be unable to attend the school. This became the basis of the Margaret Gascoigne Bursary, which assists less affluent girls who wish to attend The Study. Gascoigne laid a solid foundation for a school that in the late 20th century would be transformed from a bastion of anglophone privilege to a bilingual and multicultural institution.

Ancestry.com, “1851 England census,” Thomas Gascoigne (Nottinghamshire, Nottingham, Exchange) and Rebekah Houghton (Nottinghamshire, Basford, Basford): www.ancestry.ca/search/collections/8860; “1861 England census,” Thos [Thomas] Gascoigne (Nottinghamshire, Nottingham, Park) and Rebecca Houghton (Nottinghamshire, Basford, Basford): www.ancestry.ca/search/collections/8767; “1871 England census,” Rebecca Houghton (Nottinghamshire, Basford, Bulwell) and Thomas Gascoyne [Gascoigne] (Nottinghamshire, Basford, Greasley): www.ancestry.ca/search/collections/7619; “1881 England census,” Margaret Gascoigne (Nottinghamshire, Nottingham, Sherwood): www.ancestry.ca/search/collections/7572; “1891 England census,” Margaret Gascoigne ([Nottinghamshire], Nottingham, Nottingham North West): www.ancestry.ca/search/collections/6598; “1901 England census,” Margaret Gascoigne (Westmorland, Kendal, Milnthorpe): ancestry.ca/search/collections/7814; “1911 England census,” Margaret Gascoigne (Hertfordshire, Bushey): www.ancestry.ca/search/collections/2352 (all records consulted 26 June 2023). Find a Grave, “Memorial no.108152297”: www.findagrave.com (consulted 26 June 2023). The Study Arch. (Montreal), Board of Governors minutes book, 1922–39; copy of birth certificate of Margaret Gascoigne; Margaret Gascoigne, “Proposed school for girls,” 1914, “Speech given at the exhibition of the children’s art and general work,” June 1920, “Headmistress’ report,” 1933–34; Eve Marshall, “Head mistress’ report,” December 1993; Mary Hebert, Newsletter, June 2002; photograph of Study students, 1917–18. Univ. of Oxford, Lady Margaret Hall Arch. (Eng.), college register: Margaret Gascoigne. Globe, 25 March 1932. Gillian Avery, The best type of girl: a history of girls’ independent schools (London, 1991). J. G. Batson, Her Oxford (Nashville, Tenn., 2008). A[rthur] Clutton-Brock, The ultimate belief (London, 1916). Margaret Conrad and Alvin Finkel, History of the Canadian peoples (5th ed., 2v., Toronto, 2009). Gail Cuthbert Brandt et al., Canadian women: a history (3rd ed., Toronto, 2011). John Dickinson and Brian Young, A short history of Quebec (4th ed., Montreal and Kingston, Ont., 2008). Margaret Gillett, Traf: a history of Trafalgar School for Girls (Montreal, 2000). Colleen Gray, No ordinary school: The Study, 1915–2015 (Montreal and Kingston, 2015). Katherine Lamont, The Study: a chronicle (Montreal, 1974). J.-C. Marsan, Montreal in evolution: historical analysis of the development of Montreal’s architecture and urban environment (Montreal and Kingston, 1981). Barbara Meadowcroft, Painting friends: the Beaver Hall women painters (Montreal, 1999). Nicole Neatby, “Part three: teaching and learning – introduction,” in Framing our past: Canadian women’s history in the twentieth century, ed. S. A. Cook et al. (Montreal and Kingston, 2001), 149–54. Kenneth Richmond, The permanent values in education (London, [1917]). A. M. Stella, “Obituary of Margaret Gascoigne,” Brown Book (Oxford, Eng.), December 1934 (copy at Lady Margaret Hall Arch.). The Study Chronicle (Montreal), 1917–18, 1924–31, 1934–40, 1952–53, 1958–59, 1961.

Cite This Article

Colleen Gray, “GASCOIGNE, MARGARET,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 23, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/gascoigne_margaret_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/gascoigne_margaret_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Colleen Gray |

| Title of Article: | GASCOIGNE, MARGARET |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2025 |

| Year of revision: | 2025 |

| Access Date: | February 23, 2026 |