Source: Link

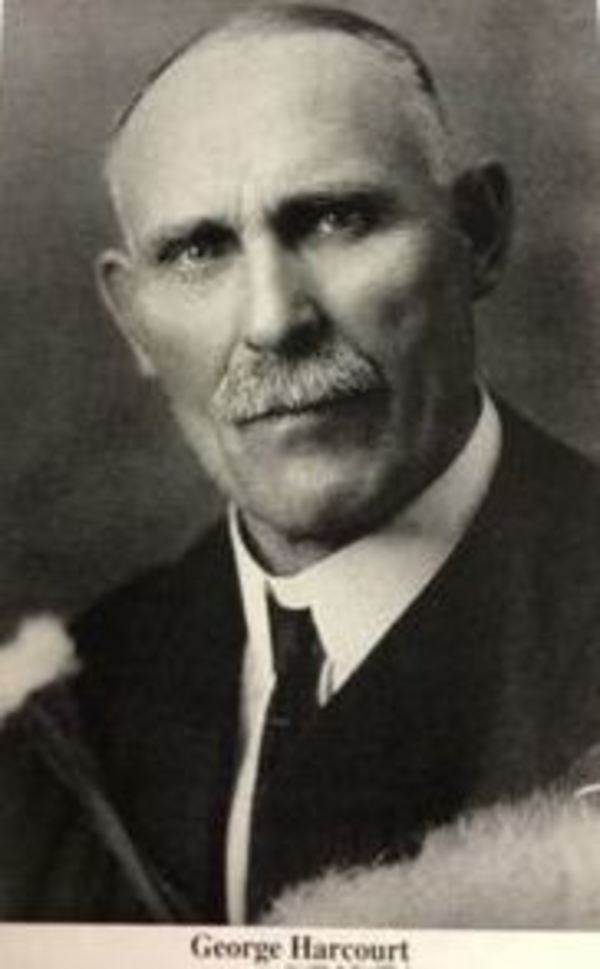

HARCOURT, GEORGE, horticulturist, professor, and civil servant; b. 3 Nov. 1863 or 1864 near Auburn, Upper Canada, son of John Tompkins Harcourt and Helen (Ellen) Ratcliffe; m. first 25 July 1893 Henrietta Jane (Jean) Stirton in Stanley, Man.; they had no children; m. secondly 12 June 1901 Ethel Jane (Jean) Cross (1876–1924) in Toronto, and they had two sons and two daughters; d. 6 Oct. 1940 in Edmonton and was buried there in Mount Pleasant Cemetery.

George Harcourt grew up on his father’s farm, and at age 25 he graduated with a gold medal for general proficiency from the Ontario Agricultural College in Guelph, Ont. He received a bachelor of science in agriculture degree from the University of Toronto in 1889 and then became an assistant to James Wilson Robertson*, a professor at the OAC. The next year, following Robertson’s departure to become the dominion’s first commissioner of agriculture and dairying, Harcourt was promoted to the position of assistant chemist and given an increased salary. From 1891 to 1894 he was professor of agriculture at Prince of Wales College, headed by Alexander Anderson*, in Charlottetown; one of his colleagues was Samuel Napier Robertson. During these years Harcourt also edited the Guardian, a local newspaper.

In 1893 Harcourt went to Manitoba to determine its potential for agriculture, and there he met and married his first wife, Henrietta, who apparently died shortly afterwards. From 1894 to 1898 he worked in Ontario as a farmer and editor, and then he decided, like many easterners at that time, to move to western Canada. He initially settled in Winnipeg, where he edited the Nor’-West Farmer between 1898 and 1903. During this period Harcourt married his second wife, Ethel, with whom he would have four children. In 1903 he was appointed superintendent of fairs and institutes for farmers, and thus joined the Department of Agriculture of the North-West Territories. The position was based in Regina, but Harcourt travelled extensively to encourage farmers to undertake experimental plantings of crops such as alfalfa, clover, field corn, and winter wheat, and to promote the use of rapeseed feedstock for hogs. He also ran an excursionist program that annually recruited thousands of young men from Ontario, Quebec, and the Maritimes to help with harvesting. He was one of many working to open the west; others were scientist William Saunders*, irrigation expert William Pearce*, and surveyor John Stoughton Dennis.

In 1905 the government of the new province of Alberta, led by Premier Alexander Cameron Rutherford*, appointed Harcourt deputy minister of agriculture. He would hold the position for ten years under ministers William Thomas Finlay* and Duncan McLean Marshall*. Finlay was ill throughout his tenure from 1905 to 1909 and Harcourt assumed his duties, a responsibility he enjoyed enormously. This was his heyday in shaping agriculture in Alberta. Harcourt established the Department of Agriculture and hired its staff. Among those he brought in was fellow OAC graduate Horace Aldridge Craig, who became superintendent of fairs and institutes and, eventually, deputy minister. Another recruit was Zechariah McIlmoyle, who was Harcourt’s assistant as well as secretary of the Board of Agricultural Education. In recognition of his double role as deputy minister and, effectively, minister, in 1908 Harcourt was elected to the senate of the University of Alberta in Edmonton.

Marshall, who succeeded Finlay in 1909, was much more capable of running the department, and his assertiveness created tension with Harcourt, who found it difficult to return to the traditional deputy minister’s role. He also believed, according to botanist Roger Vick, that Marshall was “personally extravagant at the expense of the Alberta taxpayers.” Of greater concern, beginning in 1909–10, were drought conditions in the dry-belt area of southern Alberta and Saskatchewan, a region in which the provincial governments led by Rutherford and Thomas Walter Scott, as well as Sir Wilfrid Laurier*’s minister of the interior, Clifford Sifton*, had encouraged agricultural settlement. In 1911 Harcourt argued that farmers needed support to develop better practices, and the department established demonstration farms, ranging from 160 to 640 acres in size, in Athabasca Landing (Athabasca), Claresholm, Medicine Hat, Olds, Sedgewick, Stony Plain, and Vermilion. As all but the Claresholm farm were in the ridings of cabinet ministers, the locations attracted some criticism. They were operated as mixed farms, and at one time they were connected by a train, the Mixed Farming Special, so that farmers and their families could conveniently visit, observe, and learn.

The highlight of Harcourt’s tenure as deputy minister was the seventh International Dry-Farming Congress, held from 19 to 26 Oct. 1912 in Lethbridge along with the second International Congress of Farm Women and the Conference of Agricultural Colleges and Experiment Stations. Over 40,000 people attended the exposition, and Lethbridge gained enormous publicity, according to historian Stephani Keer, as “the world’s capital of dryland farming.” The event drew officials such as Spencer Argyle Bedford, Manitoba’s deputy minister of agriculture and immigration, and politicians such as Robert Rogers and William Richard Motherwell*. It was considered a great success, yet it did little for the relief of farmers in the dry belt. Historian Curtis R. McManus observes that Harcourt had the temerity to blame farmers for “a lack of intelligent methods” and could not bring himself to use the word “drought,” instead referring to the stark conditions as “droughty.” To promote education as well as development of the province’s resources, Harcourt, Marshall, and University of Alberta president Henry Marshall Tory* championed the creation of technical agricultural schools in the province. Using funds provided by the federal government of Robert Laird Borden, in 1913 the department opened schools in Vermilion, Claresholm, and Olds. The situation continued to deteriorate in the southern region of Alberta and Saskatchewan, however, and a year later the federal and provincial governments offered settlers reduced train fares to leave and obtain work in other areas.

Over a period of several years Harcourt not only suffered professional difficulties, but also experienced a decline in his personal fortunes due to speculation in real estate with his friend Tory. When the University of Alberta’s faculty of agriculture came into being on 1 May 1915 thanks to Tory’s advocacy (and over the opposition of Calgarians such as Thomas Henry Blow, who wanted their city to have its own university), Ernest Albert Howes was named dean and Harcourt accepted the position of assistant dean. In addition, he became the faculty’s first lecturer in horticulture and would retain both posts until his retirement in 1935. Harcourt was instrumental in the creation of a four-year degree program in agriculture and then focused on horticultural work, publishing a list of recommended crops for Alberta and becoming a champion of gardening. He was particularly interested in developing hardy apples and crab apples, and he established a series of test plantings of fruits, vegetables, and ornamentals for the campus. Harcourt also helped the university to counter critics who thought it had too much influence over agriculture in the province. In 1921–22 three southern Alberta farmers asked the province to place the faculty of agriculture under the control of the Department of Agriculture, and Harcourt, with his many contacts, played an important role in the university’s successful campaign to gain the support of mlas.

George Harcourt was regarded by his peers as a fanatically hard worker, but he found time to be an active member of the Edmonton Horticultural Society as well as the Vacant Lots Garden Club, which promoted vegetable growing to address food shortages during World War I. The club would also be important during the Great Depression, when it allocated lots rent-free to citizens on relief. In 1928 Harcourt used the university’s CKUA radio network to lecture on the subjects of hotbeds and cold frames, vegetable gardening, and the beautification of home grounds. During his retirement he gave talks across the prairies in the Canadian Pacific Railway’s Tree Planting Car, a travelling horticultural exhibit. In 1955, 15 years after his death, the University of Alberta introduced a new variety of apple, the Harcourt, to celebrate his legacy. His residence in Edmonton’s university neighbourhood of Windsor Park is included in the register of Canada’s Historic Places.

Univ. of Alta Arch. (Edmonton), Dept. of plant science fonds. Maureen Aytenfisu, “The University of Alberta: objectives, structure and role in the community, 1908–1928” (ma thesis, Univ. of Alta, 1982). Kathryn Chase Merrett, “Edmonton Horticultural Society: the history of EHS”: edmontonhort.com/history (consulted 24 April 2017). The encyclopedia of Canada, ed. W. S. Wallace (6v., Toronto, [1948]). The first fifty years: a history of the faculty of agriculture, 1915–1965, ed. W. E. Bowser ([Edmonton, 1965]). D. C. Jones, Empire of dust: settling and abandoning the prairie dry belt (Edmonton, 1987). Stephani Keer, “Lethbridge was the world’s capital of dryland farming, and then …,” in Alberta in the 20th century: a journalistic history of the province in twelve volumes, [ed. Ted Byfield et al.] (12v., Edmonton, 1991–2003), 3 (The boom and the bust, 1994), 150–63. C. R. McManus, Happyland: a history of the “Dirty Thirties” in Saskatchewan, 1914–1937 (Calgary, 2011). E. B. Swindlehurst, Alberta’s schools of agriculture: a brief history ([Edmonton, 1964?]). Roger Vick, “George Harcourt, horticulturist,” Alberta Hist. (Calgary), 39 (1991), 3: 21–25.

Cite This Article

Adriana A. Davies, “HARCOURT, GEORGE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 31, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/harcourt_george_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/harcourt_george_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Adriana A. Davies |

| Title of Article: | HARCOURT, GEORGE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2021 |

| Year of revision: | 2021 |

| Access Date: | December 31, 2025 |