Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

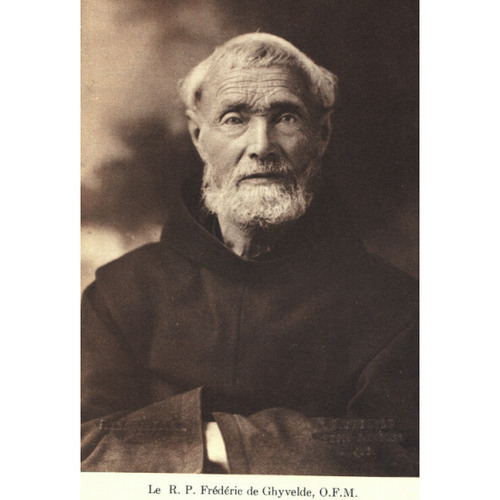

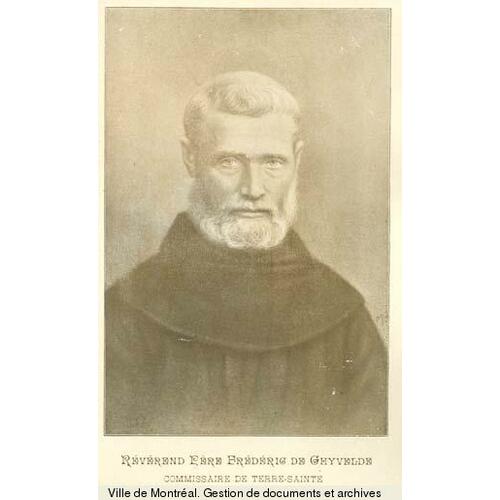

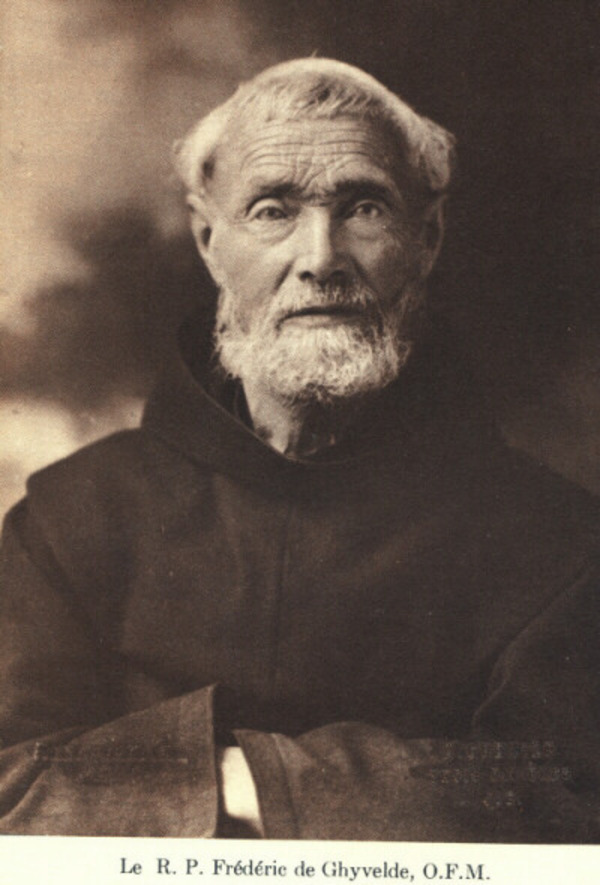

JANSSOONE, FRÉDÉRIC (baptized Frédéric-Cornil, called Brother Frédéric-Yves or Frédéric de Saint-Yves in several documents from his early days with the Franciscans, but later commonly known as Father Frédéric Janssoone or Frédéric de Ghyvelde and, in Quebec, as “Good Father Frédéric”), priest of the Order of Friars Minor, popular preacher, and writer; b. 19 Nov. 1838 in Ghyvelde, France, eighth and youngest child of Pierre-Antoine Janssoone and Marie-Isabelle Bollengier; d. 4 Aug. 1916 in Montreal.

Although born in France, Frédéric Janssoone was of Flemish descent and his mother tongue was Flemish. His father, a farmer, had achieved a fairly comfortable standard of living by hard work. His mother, whose first husband had been a physician, was an educated and refined woman. The couple gave young Frédéric a rigorous education, with emphasis on self-control, integrity, and courtesy. Above all, they instilled in him their deep faith and Christian charity. Frédéric attended elementary school in his village. On 13 Jan. 1848, at the age of nine, he lost his father. Four years later, feeling drawn to the priesthood, he enrolled in the Collège d’Hazebrouck, and shortly thereafter in the Institution Notre-Dame des Dunes, near Dunkirk. At both establishments he proved a diligent and exemplary student and achieved excellent academic results. In 1855, however, his mother fell on hard times and he had to interrupt his studies in order to help his family. He found work with some textile merchants. He was paid little at first, but soon, thanks to his business acumen and talent for selling, he became a prosperous travelling salesman. His genius for business would always remain one of his gifts.

Following his mother’s death in 1861, Janssoone resumed and completed his studies in the humanities, and on 26 June 1864 he joined the Order of Friars Minor (commonly called Franciscans) in Amiens. He was ordained to the priesthood in Bourges on 17 Aug. 1870. Since France and Prussia were then at war, his ordination was moved forward a little so he could become a chaplain in a military hospital. After the war he helped found a friary in Bordeaux, and he became its superior in 1873. Since he found the role unbearable, he was relieved of this responsibility a year later. His release gave him the freedom to take an approved course in practical homiletics, at which he would excel all his life.

In 1876 Father Frédéric obtained permission to go to Palestine, where the Franciscans had an international province of 350 members, known as the Custodia of the Holy Land and directed by a superior with the title of custos. His first assignment took him to Cairo, Egypt, as chaplain to the Brothers of the Christian Schools. In 1878 his superiors recalled him to Jerusalem and appointed him custodial curate or assistant to the custos, an office he held until 1888. It involved heavy administrative duties, one of the most onerous being to look after the custodia’s buildings. As part of these responsibilities, Father Frédéric built the parish church of St Catherine in Bethlehem, beside the Church of the Nativity (from where the Christmas midnight mass is still broadcast to the entire world). With all the political and religious rivalries troubling the country, which was under the Ottoman regime, this achievement required prodigious feats of diplomacy and tact on the part of the custodial curate. But he needed even more patience and subtlety to formulate the famous rules for Bethlehem and the Holy Sepulchre, priceless manuscript documents that finally codified the rights of the Latins, Greeks, and Armenians, all of whom used the two great sanctuaries in Palestine. This meticulous compilation, which he would complete in 1888, is still the Magna Carta governing the conduct of the Franciscans who live in these holy places of the Christian faith.

His technical duties did not prevent Father Frédéric from being an exceptional leader of pilgrimages. During his ten years in Jerusalem he welcomed and guided pilgrims from all parts of Christendom with the competence of an expert and the zeal of an angel. Through this work he came in contact for the first time, on 31 March 1881, with Abbé Léon Provancher*, the curé of Cap-Rouge, near Quebec, who brought him to Canada that summer.

Father Frédéric’s initial visit to Quebec was a fund-raising tour occasioned by the fact that charitable donations promised for the construction of St Catherine’s Church were slow in coming. He arrived in Lévis from New York on 24 Aug. 1881. Apart from the political uproar caused by an ill-advised speech on liberalism that he gave at Quebec on 10 Sept. 1881 (the hapless visitor was unaware of the fierce disputes on this subject that divided French Canadian politicians and bishops) his campaign was a triumph. The sermons he preached in Quebec City and Trois-Rivières met with tremendous success. On 24 March 1882 Archbishop Elzéar-Alexandre Taschereau* of Quebec, who in the interest of keeping the peace after Father Frédéric’s speech had asked him to leave the diocese temporarily, crowned his mission by publishing a pastoral letter which ordered that a collection for the Holy Land be taken in all the churches of the ecclesiastical province of Quebec every year, on Good Friday. A century later this custom is still followed in every Catholic church in Canada.

In May 1882, exhausted and ill, the custodia’s envoy returned to Jerusalem, where he remained for six years. During all this time French Canadians, who saw him as the ideal successor to their first missionaries, the Recollets, kept asking the Franciscan authorities to let them have him. Their wishes were finally granted in 1888 when Father Frédéric returned to Canada to stay. He arrived at the end of June and by August had begun building a small Holy Land commissariat in Trois-Rivières, the first Franciscan house to be erected in the country since the disappearance of the Recollets. For the next 28 years, from this modest pied-à-terre and the regular friary replacing it in 1903, the missionary from the Holy Land would go out to every diocese in Quebec and even to New England. These years of intense missionary work fall into two main phases.

The first phase covers Father Frédéric’s 14 years as chief organizer of the pilgrimage to Notre-Dame-du-Cap, a Marian shrine several miles from Trois-Rivières. It was a task he had accepted much against his will, at the request of Bishop Louis-François Laflèche* of Trois-Rivières, who wanted to revive and consolidate the work done by curé Luc Desilets*. During this period the dynamic little friar travelled all through Quebec in search of pilgrims, bringing them to Cap-de-la-Madeleine by the train- and boatload, leading them, exhorting them, getting them to pray, and finally consecrating them to Our Lady of the Rosary. Sensational cures gave credibility to his work, so that a small parish pilgrimage soon became a diocesan one and then verged on being a national one. By the time the Oblates of Mary Immaculate took over responsibility for it in 1902, the crowds had been averaging 30,000 to 40,000 annually for a couple of years. It is not surprising that Bishop François-Xavier Cloutier* of Trois-Rivières, speaking at his funeral in 1916, would see fit to remind the huge crowd, “It was Father Frédéric too, who, in large measure, began the work of Our Lady of the Rosary at Cap-de-la-Madeleine.”

In 1895, however, before his commitment at Notre-Dame-du-Cap was finished, Father Frédéric began the famous fund-raising drives that he was to conduct for some 15 years throughout a number of Quebec dioceses. This was the second of the great tasks to which he devoted his energy in Canada. Begun at the request of his superiors, these exhausting campaigns were intended to support diocesan or Franciscan works such as the Sanctuaire de l’Adoration Perpétuelle at Quebec, the monasteries of the Poor Clares in Salaberry-de-Valleyfield and the Sisters Adorers of the Precious Blood in Joliette, and the Franciscan friary in Trois-Rivières. Wearing a wretched skimpy brown coat, fasting and sleeping on the ground, Father Frédéric went from parish to parish and from house to house, braving inclement weather, bad roads, and farm dogs, preaching in the churches, comforting the sick and afflicted, and selling his books for the benefit of the causes entrusted to him, while keeping a small commission for the Holy Land. Thus he returned to some extent to his former occupation: he was now God’s travelling salesman. Charmed by his gentleness and courtesy, edified by his deep piety and incredible austerity, and above all amazed by the marvels that occurred here and there in his wake, the faithful saw him as another Francis of Assisi and were in the habit of calling him “the Holy Father.”

The energy he expended on these exhausting tasks did not prevent Father Frédéric from taking on many other activities. He very effectively looked after the interests of his beloved Holy Land, set up open-air stations of the cross, preached at parish and community retreats, accompanied various pilgrimages to Sainte-Anne-de-Beaupré as well as to Cap-de-la-Madeleine, inaugurated and visited brotherhoods of the Third Order, and quietly set about preparing for the re-establishment in Canada of the Order of Friars Minor, which had disappeared in 1849 with the death of the last Recollet. He also founded two magazines, the Annales du T. S. Rosaire (Cap-de-la-Madeleine) in 1892 and the Revue eucharistique, mariale et antonienne (Québec) in 1901, for which he wrote many of the articles. By sacrificing his sleep, he produced an astonishing series of publications: newspaper and magazine pieces, pamphlets, works on the Holy Land and spirituality, and thick volumes on the lives of Jesus, Mary, St Joseph, St Anne, St Francis of Assisi, St Anthony of Padua, and the Recollet Brother Didace Pelletier*. And he knew how to make his books sell. For example, the Vie de N-S. Jésus-Christ, which was published at Quebec in 1894, would go through some ten editions with a record print-run of 42,000 in all.

Worn out by austerity and work and afflicted with stomach cancer, Father Frédéric had to take to his bed in June 1916. On 4 August, after 50 days of terrible physical and mental suffering, he died quietly in the Franciscan infirmary on Rue Dorchester (Boulevard René-Lévesque) in Montreal. His body was brought back to Trois-Rivières, where it remains. Eleven years after his death, steps were initiated to have him beatifed by the church. After an informative process in Trois-Rivières in 1927, there were additional ones in Lille, France, and Alexandria, Egypt, between 1930 and 1933. The procedure culminated on 25 Sept. 1988 in a solemn beatification proclaimed by Pope John Paul II in St Peter’s Square in Rome before a crowd of 50,000.

Father Frédéric was of average height (about five feet seven inches), but slight of frame and so thin (possibly 115 pounds) that he seemed frail and puny. And yet he had incredible endurance. For years he worked 14 or 15 hours a day, despite frequent and acute stomach pains and a regimen of insufficient food. He referred to his “sickly iron constitution.” Everyone wondered how such a small man could do so much on so little sleep and nourishment.

By nature he was a lover of many things. His interests, as shown by his notebooks and letters, ranged from mysticism to the growing of beets and raspberry canes and encompassed theology, philosophy, literature, painting, history and geography, archaeology and palaeography, astronomy, biology, and botany. He might have spent his life flitting from one passing concern to another if his temperament had not been disciplined early by a strong and austere education. His Franciscan teachers, in taking over from his family, not only strengthened his sense of discipline and asceticism, but gave him something more by instilling in him a fairly rigid concept of obedience. As a result, the young man’s chaotic tendencies were brought under control for life and his formidable dynamism was able to achieve its full potential thanks to intelligent superiors, especially Father Raphaël Delarbre d’Aurillac and Father Colomban-Marie Dreyer, who channelled it and put it judiciously to use. On the other hand, the treatment, which on the whole certainly proved beneficial, may have slightly hardened his superego and weakened his fighting spirit. Throughout his life Father Frédéric had an overscrupulous conscience and a firm distaste for the office of superior. He was an élite lieutenant rather than a commander-in-chief, an instrument of peace rather than a redresser of wrongs.

Father Frédéric had neither taste nor talent for confrontation, but he was nevertheless an exceptional mover of men. He could influence people by using his ability to communicate and persuade, a talent which makes good salesmen and great orators. He possessed this gift to a degree that made him the equal of the most famous preachers of his order. Without gesturing grandly or raising his voice, and often with his eyes closed, he could speak for hours to devout crowds who never tired of listening. One day, in the church of Sainte-Marie-Madeleine in Cap-de-la-Madeleine, he preached a four-hour sermon at the stations of the cross, during which his audience, women from Montreal belonging to the Franciscan Third Order, apparently found “the time relatively short.”

Father Frédéric’s preaching sounded like an informal talk, but it had a bit more hidden in it than was apparent. In order to reach his listeners more effectively, the holy man did not hesitate to dramatize or play to the utmost on their sensibilities. Many tears were shed during his sermons. Eager to be edifying, he always paid close attention to his appearance in public. Hence in group photos he often looks stiff and stilted, a posture out of keeping with his true temperament, which was kind and cheerful. But all these pious artifices, which irritated some of his colleagues, stemmed from his desire to save souls, a desire the crowds recognized. In common with all saints, he radiated a kind of spiritual aura which, like the Old Testament shekinah, was a true and palpable sign of the presence of God. Father Edmond Gaudron, who made his acquaintance at the Collège Séraphique de Montréal towards the end of his life, has described this phenomenon very well: “He was the one who made God appear to men who could not see God.”

All in all, the role Father Frédéric played in Quebec was analogous to the one played in France by his compatriots Jean-Baptiste-Marie Vianney and Thérèse Martin: that of a living witness to the reality and holiness of God. It is to his credit that he succeeded in keeping to this path. When he arrived in Canada in 1881 the controversy about liberalism was raging. Abbé Desilets, his host, reportedly wanted to recruit him to support ultramontanism, a cause his bishop, Mgr Laflèche, also espoused. Between 1882 and 1888, however, the missionary from the Holy Land had time to ponder the question and decide on the course to pursue. In 1884 he wrote to his friend Provancher, another ardent ultramontane, that should he ever return to Canada, his work would be “exclusively a mission of charity, penitence, and peace.” It was a strictly spiritual program, patterned almost literally after the one St Francis of Assisi and his disciples had followed at the beginning of the 13th century. The sole objective of all his efforts during the 28 years he spent in the country was to win for God and for Christ the Canadians whom he loved so dearly, and to enhance their spiritual lives as much as possible.

This entirely disinterested evangelization produced a bonus: the flowering in Quebec of genuine tenderness towards the Franciscans, who were presented in such an amiable and courteous guise. As Father Dreyer clearly saw, this public affection fostered in turn the development of the new province of Saint-Joseph du Canada. Father Frédéric was not only the advance scout and diplomatic forerunner of this province, he was also its hidden parent, its true spiritual father, both through the influence he exerted on his first recruits and through the wider impact he had had on the milieu that had provided them. It is another glory to be added to those he had already earned as co-founder of the Sanctuaire de Notre-Dame-du-Cap and eminent evangelizer of French Canada.

[Any serious researcher wishing to write about Father Frédéric Janssoone must begin with a careful examination of the bibliographic research done on him by Father Hugolin Lemay*, whose scholarship is notable for its precise information and clear presentation. The first four parts of his earlier study, Les manuscrits du R.P. Frédéric Janssoone, o.f.m.: description et analyse (Florence, Italie, 1935), describe manuscripts by Father Frédéric held in Trois-Rivières, Que., Montreal, Jerusalem, and Bethlehem. The fifth and final part enumerates his handwritten letters, of which Father Lemay identified and studied 384. His later monograph, Bibliographie et iconographie du serviteur de Dieu, le R.P Frédéric Janssoone, o.f.m.: 1838–1916 (Québec, 1932), lists the books and articles published by Father Frédéric (131 items) as well as works concerning him (117 items).

It is obvious that these two works need to be brought up to date; however, they remain indispensable for opening the way to the researcher, who, once oriented, may turn to Trifluvianen; beatificationis et canonizationis servi Dei Friderici Janssoone positio . . . super virtutibus (Rome, 1978), an account of the discussions at the Sacred Congregation for the Causes of Saints preceding the pope’s proclamation of Janssoone’s heroic virtues. The report includes a 447-page dossier containing the main testimony heard during the informative and apostolic processes. The three most interesting testimonials are those of Abbé Louis-Eugène Duguay, which is very thorough as well as laudatory (49 pages); Father Valentin-Marie Breton, a colleague and penitent of Father Frédéric, which is much more critical (5 pages); and Mgr Colomban-Marie Dreyer, which demonstrates balance and sound judgement (36 pages).

In addition to the primary sources, the following studies can be recommended: Romain Légaré, Un apôtre des deux mondes, le père Frédéric Janssoone, o.f.m., de Ghyvelde (Montréal, 1953), the first true biography of Father Frédéric, which is stylistically awkward because as a synthesis it is not fully developed (an English version is available under the title An apostle of two worlds: Father Frederic Janssoone, o.f.m., of Ghyvelde, trans. Raphael Brown, Trois-Rivières, 1958); Un grand serviteur de la Terre sainte: le père Frédéric Janssoone, o.f.m. (Trois-Rivières, 1965), by the same author, which provides an excellent overview of Janssoone’s work in the Holy Land; Léon Moreel, Un grand moine français, le R.P Frédéric Janssoone, o.f.m., apôtre de la Terre sainte et du Canada (Paris, 1951), which is somewhat unreliable for the Canadian portion of Father Frédéric’s life, but useful for the part dealing with his native land; P.-E. Trudel, Le serviteur de Dieu, père Frédéric de Ghyvelde, et Bethléem (Trois-Rivières, 1947), a meticulous and reliable study which provides a detailed picture of Father Frédéric’s work in Bethlehem and explains the full scope of the research he conducted there and the importance of the rules he formulated; and the same author’s Monseigneur Ange-Marie Hiral, o.f.m. (5v., Montréal, 1957–61), especially vol.2, which details the obstacles Father Frédéric encountered in his efforts to prepare for the establishment of the Franciscans in Montreal, and vol.5, which roughly outlines the history of their establishment in Trois-Rivières.

Upon the announcement of Father Frédéric’s beatification in 1987, a revision of the biography by Father Légaré became necessary. Since he had died in 1979, Father Constantin-M. Baillargeon was asked to rewrite the volume and make any necessary corrections and additions. Published under the names of both authors, Le bon père Frédéric (Montréal, 1988) constitutes the official account of the beatification and the most complete and up-to-date biography of Father Frédéric. André Dumont’s study, Le goût de Dieu: message spirituel du père Frédéric, franciscain, d’après ses lettres (Cap-de-la-Madeleine, Qué., 1989), is a felicitous complement to this biography. A methodical examination of Janssoone’s writings, this work reveals a secret and warmhearted Father Frédéric largely unknown to the public, and brings out the main themes of his spirituality.

On the occasion of Father Frédéric’s beatification, numerous articles and publications, written for the general public, capitalized on the information provided in the aforementioned works. Two small publications among them worth noting are J.-F. Motte, Frédéric Janssoone de Ghyvelde: franciscain apôtre du Christ en trois continents, France (1838–1876), Terre sainte (1876–1888), Canada (1888–1916) (Paris et Montréal, 1988), and Léandre Poirier, Good Father Frederick, a Franciscan apostle, 1838–1916, trans. Kevin Kidd (Montreal, 1988); the latter work was also translated into Korean by Agatha Kim and published at Seoul in 1990. c.-m.b.]

Cite This Article

Constantin-M. Baillargeon, “JANSSOONE, FRÉDÉRIC (baptized Frédéric-Cornil) (Brother Frédéric-Yves, Frédéric de Saint-Yves, Father Frédéric Janssoone, Frédéric de Ghyvelde, Good Father Frédéric),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 8, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/janssoone_frederic_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/janssoone_frederic_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | Constantin-M. Baillargeon |

| Title of Article: | JANSSOONE, FRÉDÉRIC (baptized Frédéric-Cornil) (Brother Frédéric-Yves, Frédéric de Saint-Yves, Father Frédéric Janssoone, Frédéric de Ghyvelde, Good Father Frédéric) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1998 |

| Year of revision: | 1998 |

| Access Date: | March 8, 2026 |