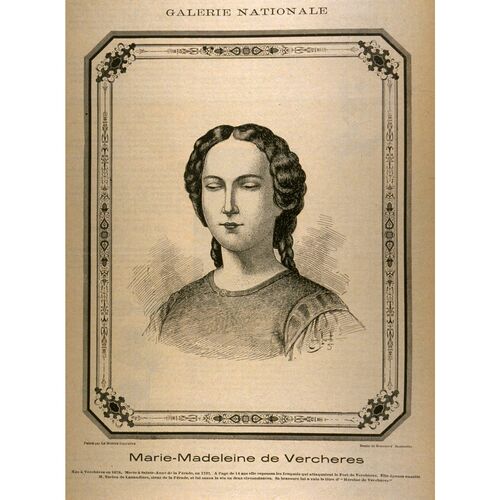

JARRET DE VERCHÈRES, MARIE-MADELEINE (baptized Marie-Magdelaine, more often called Madeleine, and sometimes Madelon) (Tarieu de La Pérade), b. 3 March 1678 at Verchères (Que.) and baptized 17 April in the parish of Saint-Pierre at Sorel (Que.), fourth of the 12 children of François Jarret de Verchères and Marie Perrot; buried 8 Aug. 1747 at Sainte-Anne-de-la-Pérade (Que.).

Madeleine’s father, François Jarret, originally came from Saint-Chef (dept. of Isère), France. Born around 1641, he was about 24 when he landed at Quebec in August 1665 with the company commanded by his uncle, Antoine Pécaudy* de Contrecœur, in the Régiment de Carignan. Once peace with the Iroquois (Haudenosaunee) had been established he decided to settle in Canada, following his uncle’s example. On 17 Sept. 1669 he married a peasant girl of twelve and a half years of age, Marie Perrot, at Sainte-Famille, Île d’Orléans. Jarret himself was not “of noble birth” as has been said: in 1672 and 1674 Governor Frontenac [Buade*] sought letters of nobility for him, without success, in recognition of his continuing services.

François Jarret’s title as an ensign in the Carignan regiment, and, probably, his uncle’s support, brought him a land grant by Intendant Talon* on 29 Oct. 1672. The new seigneury, called Verchères, was on the south shore of the St Lawrence and initially had a frontage and depth of a league, before it was enlarged in August 1673 by two islands directly in front of it: the Île aux Prunes and the Île Longue. In October 1678 – the year of Madeleine’s birth – another league was added to the back of the original grant.

Although M. de Verchères campaigned occasionally, he did not neglect his seigneury. In 1681 he had at least 11 censitaires, and some 120 acres of land under tillage. The seigneur himself had 20 acres, and, according to the census, 13 cattle and five muskets. The firearms – there were 15 in the seigneury – were necessary; Iroquois raids were once again on the rise in the region, the most exposed in Canada because of the proximity of the Richelieu River (or “Rivière des Iroquois”) which this formidable enemy used to penetrate the colony. Verchères and the neighbouring lands of Contrecœur and Saint-Ours were to be threatened still more in the terrible years to come, for the Iroquois used them as short cuts to avoid the fort at Sorel.

Like many other seigneurs, M. de Verchères had a fort built for the protection of his family and censitaires: a rough, rectangular stockade 12 to 15 feet high, with a bastion at each corner; it had no moats, and a single gate on the river side. Inside were the seigneur’s manor-house, a redoubt which served as guardhouse and magazine, and probably some temporary building which could shelter the women, children, and animals in case of danger. One or two guns, probably just swivel guns intended to sound the alarm rather than repulse the enemy, completed this modest defensive system.

The years went by, and the seigneur’s children grew rapidly, at least those who survived. In 1692, when Madeleine was nearing 14 years of age, she had already lost her elder brother Antoine, who had died in 1686; two brothers-in-law, both of whom had been married to Marie-Jeanne, had been killed by the Iroquois, one in 1687, the other in 1691; her brother François-Michel, was also slain by the Iroquois in 1691 at 16 years of age. Six brothers and sisters came after her, their ages varying from 12 to two (two boys had not yet been born).

One day in 1690 there had been serious alarm close to the manor-house, and the little group had been in great danger. Knowing that it was almost defenceless, the Iroquois tried to scale the stockade; a few musket shots made them fall back at first. Mme de Verchères, who was 33 at that time, had only three or four men with her. She took command and repulsed the attackers several times. Did she sustain the attack in the fort, as Charlevoix maintains, or in a redoubt more than 50 paces outside the stockade, as La Potherie [Le Roy*] claims? It does not much matter. According to Madeleine the redoubt was within the walls of the fort: it would have served as a stronghold if the Iroquois had breached the stockade. The siege lasted two days, and with the bearing of a veteran Mme de Verchères finally forced the enemy to retreat. She had lost only one combatant, whose name was L’Espérance.

The same scene and the same peril were to be repeated two years later. Mme de Verchères would be absent this time, in Montreal, as was her husband, called to Quebec. It was Madeleine who, in her 15th year, would have to play the role her mother had played so well in 1690. Had the girl helped her at that time? Instinctively she assumed the same attitude and carried out the same actions, adding, it appears, a dash of boldness.

There are five accounts of the siege of 1692: two by Madeleine herself, two by La Potherie (in the same work, the second correcting in part the first), and one by Charlevoix. They were all composed after the event: Madeleine’s first account being the closest to it, although it was not made until 15 Oct. 1699; her second was not made before 1722; La Potherie’s and Charlevoix’s date respectively from about 1700 and 1721. The heroine’s original narration, contained in a letter to the Comtesse de Maurepas, was attested to by Intendant Champigny [Bochart*]. It agrees fairly well with those by La Potherie and Charlevoix, since Charlevoix had followed La Potherie and La Potherie, who knew Madeleine, had certainly seen her letter, if indeed he had not suggested it to her himself, dictating it to her word by word.

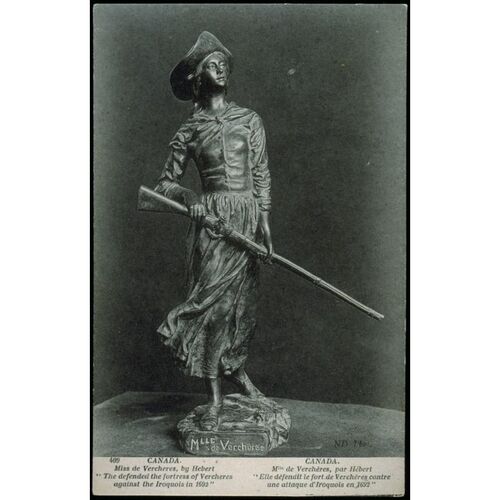

On 22 Oct. 1692, at eight o’clock in the morning, with only one soldier on duty at the fort of Verchères, some Iroquois, who had been hiding in the thickets nearby, suddenly seized some 20 settlers working in the fields. Madeleine, who was 400 paces from the stockade, was pursued and quickly overtaken by an Iroquois who seized her by the kerchief she was wearing around her neck; she loosened it and rushed into the fort, closing the gate behind her. Calling to arms and without stopping to listen to the cries of some women who were distressed at seeing their husbands carried off, she wrote, “I went up on the bastion where the sentry was . . . I then transformed myself, putting the soldier’s hat on my head, and with some small gestures tried to make it seem that there were many people, although there was only this soldier.” She fired a round from the gun against the attackers, which “fortunately had all the success I could hope for in warning the neighbouring forts to be on their guard, lest the Iroquois do the same to them.”

According to La Potherie the noise of the cannon “struck [the Iroquois] with terror, upset all their calculations and at the same time signalled all the forts on the north and south shores of the river from Saint-Ours as far as Montreal to be on their guard. With each fort passing the word on to the next after the first signal from Verchères, up to Montreal, a hundred men were sent to bring it help, which arrived shortly after the Iroquois had disappeared into the woods.”

Charlevoix, the least exact of the three narrators, agrees with La Potherie by putting Madeleine 200 paces from the fort when the Iroquois appeared, but he simply states that all the settlers were taken by the Iroquois, who pursued Madeleine until one of them had seized her by her neckerchief. La Potherie, on the contrary, gives more details than Madeleine does, saying that 40 to 50 Iroquois surrounded the fort after seizing 22 settlers, 20 of whom were burned, and that two Iroquois fired on the girl during the pursuit (first account); that (second account) 40 Iroquois, after taking a score of settlers threatened the fort and fired four or five rounds with their muskets at Madeleine, without wounding her. For the rest, the narratives agree; in the end the heroine’s first account, simple and plausible, seems the one most deserving of belief.

Up to this point there is nothing astonishing and nothing to make the daughter’s resistance more noteworthy than the mother’s – unless it were Madeleine’s age; but in New France many girls of 14 were married and had children, or, like Madeleine’s sister Marie-Jeanne, were already widowed. As for the 20 settlers burned by the enemy, La Potherie himself set the facts straight by telling later how a party of friendly Indigenous people freed these unfortunates in the region of Lake Champlain. The absence of civil records and the silence of the authorities prevent us from knowing how many victims there were. They could not have been numerous, since of the 11 tenants in 1681, eight died before or after this affair – and the other three need not have perished in it. In her second account Madeleine speaks of only two deaths.

About Madeleine’s first account there is a disturbing fact which historians have not noted, namely the perfect concordance between her narration and La Potherie’s second one, the correspondence often being word for word:

Madeleine: “Comme je conservé, dans ce fatal moment, le peux dasseurance Dont une fille est Capable et peut être armée, Je luy Laissay entre Les mains mon mouchoir de Col et Je fermay la porte sur moy en Criant aux armes et sans marrester aux gemissement de plusieurs femmes désolées de voir enlever leurs Maris, Je monté sur le bastion où estoit le sentinelle.”

La Potherie: “mais elle conserva dans le moment plus d’assurance que n’en pouvait avoir une Fille de quatorze ans, elle lui laissa entre les mains son mouchoir de col se jettant dans son Fort, dont elle ferma la porte sur elle en criant aux armes, & sans s’arrêter aux gémissements de plusieurs femmes désolées de voir enlever leurs maris, elle monta sur un Bastion où était la Sentinelle.”

And so on, except for some details.

Is it possible that Madeleine was not the author of the account attributed to her, having simply copied the text composed by La Potherie? In that event her testimony would not be as spontaneous or as naïve as has been believed. Or was it the terrible La Potherie who plagiarized Madeleine? As a consequence one would have to deduce that the details given by him and taken up in part by Charlevoix, all of them tending to dramatize the action, had been rejected by Madeleine as not being in keeping with the truth or had been invented outright by La Potherie after the event, which amounts to the same thing. Or had Madeleine not wanted to scare the Comtesse? An oratorical preamble at the beginning of her letter might suggest it: “Although my sex does not permit me to have inclinations other than those it demands of me, allow me nevertheless, Madame, to tell you that, like many men, I have feelings which incline me to glory.” On balance, and since we are in doubt, we must keep to the account signed by the heroine and witnessed by Champigny.

It is not the first account that is perplexing but the second one, which was first published in 1901 and which launched the “legend” of Madeleine. Much more detailed and dramatic, it constantly puts the heroine in the forefront. It differs from the first on several points and sometimes fills it out. There are now 45 Iroquois pursuing her, who give up trying to catch her and fire on her; the shots from 45 muskets whistle about her ears, she writes. The episode of the kerchief, which is no longer believable, disappears from the story. Once she is inside the fort she no longer rushes to the bastion, but instead inspects the stockade and repairs the holes in it, setting the stakes up again herself with the help of the people present, more numerous than one would have thought. In addition to the women and children, whom she tries to quiet, there are her servant Laviolette, her two young brothers, Pierre* and Alexandre, 12 and 10 years old, an 80-year-old man, and two soldiers, Labonté and Galhet, whom she finds in the redoubt, terrified and ready to set fire to the stocks of powder. All these people shoot at the enemy, even firing the cannon under the direction of Madeleine, her hair in disorder and a man’s hat on her head. This combat goes on for a week, before M. de La Monnerie comes to the rescue with a detachment sent from Montreal by Louis-Hector de Callière*.

Gone are the sobriety, the moderation, and the plausibility of the earlier account. Who will believe that a 14-year-old girl outran 45 Iroquois over a distance of 5 arpents (1,000 feet), when no white man could? Or that 45 muskets all missed her, when the Iroquois, half a century earlier, had been using them “with skill and daring,” according to the Jesuit Barthélemy Vimont*? How was she able, without any accident, to repair the holes in a wall surrounded by the enemy, with her men busy fixing the heavy stakes in place instead of keeping the attackers at bay? Finally, is it conceivable that the siege lasted a week if, as all versions say, she gave the alarm by firing the gun at the very beginning? The distance between Montreal and Verchères (about 12 leagues) was not so great that it took a week to cover it sailing down the river. Help had reached her mother in less than two days in 1690. If the siege had lasted so long, Madeleine would have said so in her first account, and La Potherie would have expressed himself quite differently in the text quoted above.

The Iroquois, moreover, were not acquainted with siege techniques and never lingered when, the first moment of surprise being past, a counter-attack was made. As they had no defensive arms and did not like costly victories, they did not expose themselves, counting only on ruse to win. Madeleine knew this: on the first night cattle that had escaped being slaughtered came to low at the gate of the fort; immediately she thought that it might be a “trick” by the enemy, whom she imagined coming behind the animals, covered with skins. In addition, the cannon terrified the assailants: according to La Potherie the first shot Madeleine fired from it “upset all their calculations.” Finally, it was customary for the Iroquois to retreat as soon as they had taken some prisoners – they held about 20 in this case. This is certainly what they did here, as a passage by La Potherie appears to confirm. The alarm was spread with cannon from one fort to another as far as Montreal (certainly the same day, since the siege began at eight in the morning), and “scarcely was this news known than the Chevalier de Crizafi [Thomas Crisafy*] was sent by water with one hundred men . . . while fifty Indians hastened by land . . . Monsieur de Crizafi arrived an hour after the Iroquois had withdrawn, but our Indians caught up with them on Lake Champlain after a six-day march.” Must we not take this to mean that six or seven days after the beginning of the siege the Iroquois were already at Lake Champlain, having covered about the same distance as the “Indians” from Montreal, and consequently taken the same amount of time?

As in 1690 then, the Iroquois probably withdrew on the second day, shortly before the arrival of La Monnerie or Crisafy, and with all the more reason since, if we are to believe Madeleine, she had succeeded in giving them the impression that the fort was swarming with soldiers. She probably exaggerated a little in writing that for the first 48 hours she went without eating or sleeping and without going into her father’s house. Otherwise, she talks only of what took place on the first day, which she calls the day of the great battle, and on the first night, during which the Iroquois did not show themselves – probably a sign that nothing happened on the second day or on the following ones.

On the first day, according to her second account, Madeleine is supposed to have made three sorties, one, by herself, to cover the landing of Pierre Fontaine, dit Bienvenu, and his family, who arrived by canoe, and two others, with her young brothers, to pick up three bags of laundry and some blankets that she had left on the shore. Each sortie had to cover five arpents in each direction, while, according to her, the enemy surrounded the fort. “That is enough,” she wrote “to give you an idea of my assurance and calm.” In all then, she is supposed to have covered 35 arpents (a mile and a quarter) that day without a scratch, in the face of or within musket shot of 45 Iroquois. Let us speak no more of temerity, but of invulnerability and miracles, and let us keep to the first account, in which the daughter proves herself worthy of her mother, without detracting from Mme de Verchères’s achievement.

After the prisoners’ return, life went on as usual in the seigneury. For the Jarrets de Verchères two more births in 1693 and 1695 came to complete the family. The father, a half-pay lieutenant since 1694, died on 26 Feb. 1700. The pension of 150 livres he received as a former officer in the Régiment Carignan was then transferred to Madeleine in consideration of her exploit in 1692 and on condition that she provide for her mother’s needs. (Mme de Verchères was buried on her seigneury on 30 Sept. 1728.) Madeleine, who had an “agreeable personality and an energetic air, but also the modesty of her sex,” and who was a “sensible” girl, had to put off her marriage until she was 28, probably to manage the seigneury and to keep her family from falling into “the deepest poverty.” Perhaps she spent her spare time hunting, since, according to La Potherie, there was “no Canadian or officer who was a better musket shot” than she. She was married in September 1706 to Pierre-Thomas Tarieu de La Pérade, a lieutenant in a company of the colonial regular troops. In the marriage contract Madeleine declared that she was bringing a dowry of 500 livres “accumulated through her savings and care.” The couple went to live on the north shore of the St Lawrence, at Sainte-Anne-de-la-Pérade, of which Tarieu was in part seigneur.

The Sieur de La Pérade’s father, Thomas de Lanouguère*, who was born around 1644 in Mirande (dept. of Gers), France, of an old noble family, had arrived in Canada with the Régiment de Carignan. On 29 Sept. 1670 he and Edmond de Suève* bought the seigneury of Sainte-Anne, near Batiscan, from Michel Gamelain* de La Fontaine. Talon confirmed their rights to this land on 29 Oct. 1672. The co-seigneurs soon divided the seigneury between them, Lanouguère keeping the western part and Suève the eastern. In 1707 the latter was willed to Edmond Chorel de Saint-Romain, who made it over on 14 March 1714 to his brother, Francois Chorel de Saint-Romain, dit d’Orvilliers (whence the name of the fief of Dorvilliers). M. de Lanouguère, who had married Marguerite-Renée Denys de La Ronde at Quebec on 16 Oct. 1672, probably died in May 1678; he left a daughter, Louise-Rose, who became an Ursuline, and two sons, Louis, who died around 1692, and Madeleine de Verchères’s future husband, Pierre-Thomas, who was born on 11 September and baptized in Quebec on 12 Nov. 1677. On 4 March 1697 Frontenac and Champigny made a grant to Mme de Lanouguère of three more leagues to the rear of her seigneury, across its whole width, and on 6 April of that year they confirmed her property rights to the islands in front of her land; Mme de Lanouguère received a new grant of these islands on 30 Oct. 1700. Finally, on 4 Nov. 1704, she made over all her rights to the seigneury of Sainte-Anne to her son, Pierre-Thomas, who was owner through a grant made on 30 Oct. 1700 of the fief of Tarieu (measuring two leagues by one and a half) located to the north of his mother’s seigneury. Mme de Lanouguère was married again in 1708, her second husband being Jacques-Alexis Fleury* Deschambault, and went to live in Montreal. In 1721 Pierre-Thomas’s patrimony was further enlarged by a share in the seigneury of Verchères which fell to Madeleine, and on 20 April 1735 by the addition of three more leagues of land to the fief of Tarieu across its entire width.

These lands and the relations of the habitants with their seigneurs gave rise to many lawsuits, with the result that it has been possible to write articles entitled “Madeleine de Verchères, plaideuse” (“Madeleine de Verchères, litigant”) and “Madeleine de Verchères et Chicaneau” (“Madeleine de Verchères and Chicaneau”). Historians have made Madeleine responsible for nearly all these quarrels (too numerous and varied to be related here), but a closer study of each case reveals that traditional affirmations require some modification. In speaking of the first “lawsuit” for example (1708), Pierre-Georges Roy* wrote that Messrs de Suève and de La Pérade, “neighbours for 20 years, had never had words.” Scarcely had Madeleine de Verchères entered the manor-house of La Pérade,” he added, “than quarrelling began between the two neighbours over the boundaries of their land grants.” In fact there was no discussion with M. de Suève, since he had been dead for a year, but with his heir, Edmond Chorel de Saint-Romain. It was the latter who claimed a certain piece of land from M. de La Pérade, who simply asked the intendant to appoint a surveyor, promising to respect the dividing line to be traced at that time. There was thus no lawsuit, no quarrel, and in any case Madeleine had nothing to do with the matter. Pierre-Georges Roy’s account of the second “lawsuit” contains a similar error; as for the third, he blamed Madeleine for some acts of violence for which her mother-in-law, Mme de Lanouguère, was responsible. The same can be said of many of the “lawsuits” in Madeleine’s career. In about half the litigations the seigneurs of La Pérade did not initiate the legal process, and most often their rights were upheld. In the other cases they usually appear to have been justified in resorting to the courts of justice, which were generally favourable to them.

One does not, however, need to exonerate the seigneur of La Pérade and his wife entirely. Certainly the two of them were ill tempered, and on occasion they threatened and terrorized their censitaires and even committed serious acts of violence against them. M. de La Pérade in particular sometimes lost his head. A censitaire who had had to snatch a musket from his hands declared that the settlers’ lives were “in very great danger, since they are dealing with a furious man who is out of his mind, as he frequently is to everyone’s knowledge.” The seigneur’s fits of anger, and sometimes those of his wife, who strongly supported him, explain why they were not loved by those about them. Their tenants tried to avoid them, and perhaps even to do them harm: for instance, they went to have their grain ground in a neighbouring seigneury rather than at Sainte-Anne’s banal mill, and one farmer asked for the cancellation of a farm lease immediately after signing it because of the Sieur de La Pérade’s rages, which he considered a constant threat to his life. (Would these bad relations with his employees and farmers explain his recourse to enslaved workers for the labour around his house?) The parish priest himself, Joseph Voyer, did not refrain on occasion from enraging the seigneurs, who showed a little too clearly their preference for his confrère, Gervais Lefebvre from Batiscan.

For years Abbé Lefebvre acted as “director” for the La Pérade family. Suddenly in 1730 he had the two Tarieus summoned before the provost court of Quebec, complaining that Madeleine in particular had accused him in public of having composed and sung some burlesque rigmaroles full of impious, obscene, and defamatory terms, of having made insulting and salacious remarks about the La Pérade family, and having incited a woman to take a false oath by promising her absolution. The witnesses were heard, the lawyers’ addresses prepared, the speech for the prosecution delivered, and the parish priest was sentenced in a judgement rendered on 29 Aug. 1730 to pay 200 livres in damages and interest to the seigneurs of La Pérade. M. Lefebvre appealed his case to the Conseil Supérieur, where he defended himself so well that the curious judgement of the provost court was overturned on 23 Dec. 1730. Madeleine, who did not like defeats, could not resign herself to this outcome. In 1732 she sailed for France to put her case before the king’s council. She was admitted into the ministries, but the appeal was refused. Did she have time to search, as her brothers and sisters had asked her to do, for property that might belong to them in the mother country as a consequence of their father’s death? She sailed again in the spring of 1733 on the king’s ship. At the suggestion of the minister of Marine, Maurepas, however, and with the intervention of the colonial authorities the lawsuit was settled out of court by notarial deed on 21 Oct. 1733. According to the arrangement Abbé Lefebvre released M. and Mme de La Pérade from the convictions they had incurred on condition that there was no more talk of this scandalous affair on either side. Madeleine, who signed the deed in her own name and as her husband’s representative, had won the day.

Many other judicial or military exploits have been attributed to her. But legend is generous towards those who have once brought themselves to the attention of posterity. Of the three or four feats of arms claimed for her in addition to the siege of 1692, it seems that only one in 1722 must be retained, when she saved her husband’s life after he was attacked by two “colossal” Abenaki men, disabling one while the other was being subdued. Immediately she was surrounded by four enraged women who would have killed her if her 12-year-old son, Charles-François*, had not freed her from them. Madeleine recounted this action herself, and Charles de Beauharnois later verified it personally. (It was in this account that she declared she had never shed a tear.)

Madeleine died at Sainte-Anne-de-la-Pérade and was buried on 8 Aug. 1747 underneath her pew in the parish church. She was 69 years of age. A surprising number of priests were present at her funeral: the parish priests of Sainte-Anne-de-la-Pérade, Saint-Joseph (Deschambault), Sainte-Geneviève (Batiscan), Saint-Charles-des-Roches (Saint-Charles-des-Grondines), Saint-Pierre-les-Becquets (Les Becquets), and perhaps some others, had been anxious to pay her a final homage.

Pierre-Thomas Tarieu de La Pérade outlived her by nearly ten years. He was buried at Sainte-Anne-de-la-Pérade on 26 Jan. 1757, at 79 years of age.

AJTR, Greffe de Jean Cusson, 5 juin 1695; Greffe de Daniel Normandin, 14 mars 1714; Greffe d’A.-B. Pollet, 5 mars 1746. AN, Col., C11A, 18, p.69 (PAC transcript). ANQ, Greffe de Louis Chambalon, 31 août 1711; Greffe de Pierre Duquet, 7 sept. 1669, 29 sept. 1670, 27 oct. 1676; Greffe de François Genaple de Bellefonds, 4 nov. 1704; Greffe d’Henry Hiché, 21 oct. 1733; AP, Coll. P.-G. Roy, Verchères et Jarret de Verchères; AP, Madame de Maurepas; NF, Coll. de pièces jud. et not., 550½, 886, 2426, 2675; NF, Foi et hommage, passim; NF, Ins. Cons. sup., passim; NF, Ord. int., passim; NF, Registres de la Prévôté de Québec, passim; NF, Registres d’intendance, passim; NF, Registres du Cons. sup., passim. ANQ-M, Greffe d’Antoine Adhémar, 29 mars, 22 oct. 1710; Greffe de René Chorel de Saint-Romain, 6 juill. 1732; Greffe de Michel Lepailleur, 8 sept. 1706. Charlevoix, Histoire de la N.-F. (1744), III, 123–25. “Correspondance de Vaudreuil,” APQ Rapport, 1939–40, passim. “Correspondance échangée entre la cour de France et le gouverneur de Frontenac, pendant sa seconde administration (1689–1699),” APQ Rapport, 1926–27, passim; 1927–28, passim. Édits ord., II, III, passim. Jug. et délib., passim. [C.-C. Le Roy] de Bacqueville de La Potherie, Histoire de l’Amérique septentrionale . . . ([2e éd.], 4v., Paris, 1753), I, 313, 324–28; III, 150–55. PAC Report, 1899, supp., 5–12. “Recensement du Canada, 1681” (Sulte). Le Jeune, Dictionnaire. Tanguay, Dictionnaire. F.-A. Baillairgé, Marie-Madeleine de Verchères et les siens (Verchères, Qué., 1913). François Daniel, Histoire des grandes familles françaises du Canada . . . (Montréal, 1867), 447–80. A. G. Doughty, A daughter of New France; being a story of the life and times of Magdelaine de Verchères, 1665–1692 (Ottawa, 1916). Raymond Douville, Les premiers seigneurs et colons de Sainte-Anne de la Pérade, 1667–1681 (Trois-Rivières, 1946). E. T. Raymond, Madeleine de Verchères (Ryerson Canadian history readers, Toronto, [1928]). [L.-S. Rheault], Autrefois et aujourd’hui à Sainte-Anne de la Pérade; [2e partie] Jubilé sacerdotal de Mgr des Trois-Rivières (1v. en 2 parties, Trois-Rivières, 1895). P.-G. Roy, La famine Jarret de Verchères (Lévis, Qué., 1908); La famille Tarieu de Lanaudière (Lévis, Qué., 1922); Toutes petites choses du régime français (2 sér., Québec, 1944), 2e sér., 37–40. Jean Bruchési, “Madeleine de Verchères et Chicaneau,” Cahiers des Dix, XI (1946), 25–51. Philéas Gagnon, “Le curé Lefebvre et l’héroïne de Verchères,” BRH, VI (1900), 340–45. Henri Morisseau, “Pierre Fontaine dit Bienvenu: lieutenant de Madeleine de Verchères dans la défense du fort le 22 octobre 1692,” Revue de l’université d’Ottawa, XIII (1943), 163–78. P.-G. Roy, “Madeleine de Verchères, plaideuse,” RSCT, 3rd ser., XV (1921), sect.i, 63–71.

Bibliography for the revised version:

Bibliothèque et Arch. Nationales du Québec, Centre d’arch. de la Mauricie et du Centre-du-Québec (Trois-Rivières, Québec), CE401-S21, 8 août 1747; Centre d’arch. de Montréal, CE603-S7, 17 avril 1678.

Cite This Article

André Vachon, “JARRET DE VERCHÈRES, MARIE-MADELEINE (baptized Marie-Magdelaine) (Madeleine, Madelon) (Tarieu de La Pérade),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 3, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 1, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/jarret_de_vercheres_marie_madeleine_3E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/jarret_de_vercheres_marie_madeleine_3E.html |

| Author of Article: | André Vachon |

| Title of Article: | JARRET DE VERCHÈRES, MARIE-MADELEINE (baptized Marie-Magdelaine) (Madeleine, Madelon) (Tarieu de La Pérade) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 3 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1974 |

| Year of revision: | 2024 |

| Access Date: | March 1, 2026 |