Source: Link

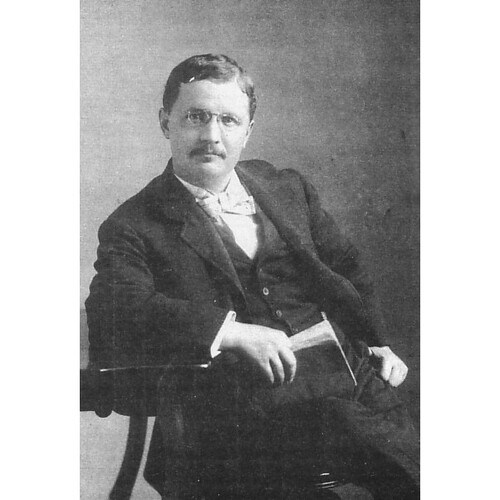

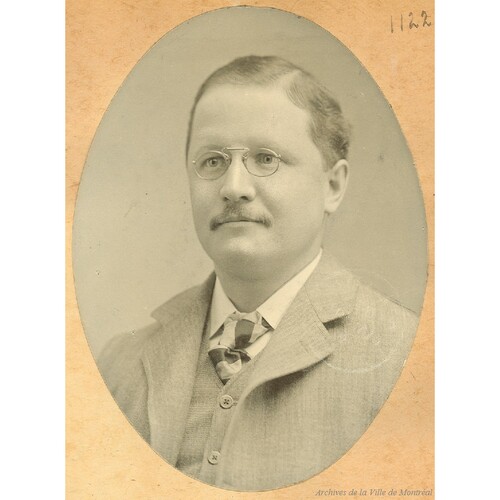

LANGLOIS, GODFROY (baptized Joseph-Ernest-Godefroi), journalist, newspaper editor, freemason, politician, and agent general for the province of Quebec in Brussels; b. 26 Dec. 1866 in Sainte-Scholastique (Mirabel), Lower Canada, son of Joseph Langlois and Olympe Clément (Proulx, dit Clément); m. 24 Jan. 1900 Marie-Louise Hirbour in Montreal, and they had one daughter; d. 6 April 1928 in Brussels, and was buried on 28 July in Sainte-Scholastique.

Godfroy Langlois’s father was a merchant and politician of considerable importance in Sainte-Scholastique. After elementary school, Godfroy was enrolled at the Petit Séminaire de Sainte-Thérèse in the fall of 1881. For reasons that are unclear, he left in June 1884 and entered the Collège de Saint-Laurent, near Montreal. He graduated gold medallist in June 1887. That September he entered the law school of the Université Laval in Montreal. Bored by the academic approach to law, he chose to pursue his legal studies as a clerk in the prestigious practice of Raymond Préfontaine* and Pierre-Eugène Lafontaine*. A few months later he moved to the firm of Toussaint-Antoine-Rodolphe Laflamme*, a prominent Rouge.

Laflamme proved to be influential. He advised Langlois to abandon law and to pursue instead a career in journalism. In December 1889 Langlois launched Le Clairon in Montreal with three other collaborators. The weekly quickly attracted attention, but could not find its niche and ceased publication in March 1890.

Langlois immediately accepted an invitation from Honoré Beaugrand* to work at La Patrie. On 6 November, while still at La Patrie, he launched L’Écho des Deux-Montagnes (Sainte-Scholastique) with lawyer Joseph-Dominique Leduc. His bold sense of liberalism flourished in this weekly, where he defined the contours of his “radicalism” more succinctly, addressing issues such as annexationism, educational reform, politics, and the abuses committed by the clergy. Édouard-Charles Fabre*, archbishop of Montreal, reacted to Langlois’s increasingly hostile attacks by banning L’Écho on 11 Nov. 1892. Langlois obstinately resumed his criticism two weeks later in a new publication, La Liberté (Sainte-Scholastique), laid out exactly as L’Écho had been, with the same number of pages, the same sponsors, and the same bylines. Educational reform assumed sovereign importance in the newspaper, as it would throughout Langlois’s career. “[The] masses must be enlightened,” he wrote, “they must know of the progress being made and they must have the tools to compete.”

Langlois continued at La Patrie until December 1893, when he accepted an offer to join Le Monde (Montréal) as assistant editor. Le Monde had been purchased by a consortium of businessmen who were eager to reorient the traditionally ultramontane daily. Under the new management, its editorial comments were few and moderate in tone, hardly in keeping with Langlois’s style. The experience in administration which he gained there would nevertheless benefit his career.

On 24 Oct. 1895 La Liberté appeared for the last time. The following day Beaugrand announced that Langlois would become managing editor of La Patrie. Félix-Gabriel Marchand*, leader of the Liberal opposition in Quebec, was infuriated by the appointment of Langlois. Federal Liberal leader Wilfrid Laurier*, who was also concerned about the rising tide of radicalism, especially in the light of his preparations for the imminent elections, was equally angered. Beaugrand stood his ground, however, and Langlois remained.

Langlois also found a fertile ground for his advanced liberalism in freemasonry. He joined the Cœurs-Unis Lodge No.45 in Montreal in December 1895. Freemasonry in Quebec at the time was dominated by the Grand Lodge of Canada and the Grand Lodge of Quebec, both of which were affiliated with British masonry. The Cœurs-Unis Lodge was a chapter of the Quebec organization. On 12 April 1896 a meeting of the Cœurs-Unis was called to ask for an alliance with the Grand Orient in France. Langlois joined the committee that petitioned for a new constitution and he proposed a name for the new lodge, L’Emancipation, that was immediately accepted.

Although enthusiasm for the lodge was strong in its first year, its handful of members met only sporadically after 1899. Langlois nevertheless remained a staunch member, rising to the presidency in 1901. An inspection report submitted to the Grand Orient in early 1903 made particular mention of his “energy” and “deep conviction.” Langlois was often publicly accused of being a freemason, a charge he never denied but often mocked. His marriage in the Roman Catholic Church and the baptism of his child there certainly colour the principles he harboured as a freemason.

On 4 Feb. 1897 Joseph-Israël Tarte* had purchased La Patrie from Beaugrand. Four days later Langlois officially penned his first comment as editor-in-chief. Fortified by his promotion, he submitted his name for the Liberal candidacy in the provincial riding of Deux-Montagnes. He was supported by local Liberal leaders, but Marchand intervened and disallowed his candidacy. About two months after Langlois became editor-in-chief Tarte demoted him to make room for the rising star in Liberal ranks, Henri Bourassa*. The new editorial director’s politics could not have been more dissimilar, but Langlois’s supporters rallied and Bourassa was forced to leave after a few days. Langlois’s stature as a leading spokesman of the unofficial progressive faction of the Liberal party was becoming clear.

A co-worker, Charles Robillard, remembered Langlois’s endearing personal qualities. “Of great simplicity, warm, affable, and obliging, a friend of the good clean joke, he knew how to bring a gaiety to everyday conversation. . . . The intransigence of his principles was forgotten when in close company, and colleagues saw before them only the most humble and charming of men.” Just over five feet tall, he was always slightly corpulent. He had clear blue eyes and had sported a pince-nez since he was in his early twenties. As soon as he could grow one, he had worn a moustache.

In November 1901 Langlois articulated the need for an organization to promote educational reform. The Ligue de l’Enseignement was officially founded in Montreal on 9 Oct. 1902. Its name deliberately evoked that of the Ligue Française de l’Enseignement and its members were drawn mainly from the progressive wing of the Liberal party. Langlois was named vice-president and secretary. The program he submitted, which was approved on 21 Nov. 1902, included improved salaries and qualifications for schoolteachers, increased government subsidies, the enforcement of current educational legislation, the building of clean, “sanitary” schools, and the centralization of the Catholic school system’s administration.

In January 1903 Tarte broke the ties between La Patrie and the Liberal party. Laurier had long anticipated the loss of the daily and had struck a committee after Tarte’s departure from cabinet in October 1902 to look into the question of launching a new paper. Senator Frédéric-Ligori Béïque* offered the necessary capital. After much deliberation, Laurier met with Langlois to discuss the tone and orientation of the new publication. There was much opposition within the party to Langlois’s appointment, but armed with Langlois’s guarantee that the paper would remain loyal, Laurier approved the preparations for a morning publication that would be called Le Canada.

Langlois quickly dedicated the newspaper, launched in April 1903, to educational and municipal reform, and mounted a campaign against the privileges of the Montreal Light, Heat and Power Company [see Louis-Joseph Forget*]. He took his crusade for good government into the provincial Liberal party during the elections in the fall of 1904. Although Le Canada did its duty by pledging its support to Premier Simon-Napoléon Parent* in its editorial of 7 November, that same night Langlois mobilized his supporters against the government. The Liberals in Division No.3 in Montreal met to reaffirm the nomination of the incumbent, Henri-Benjamin Rainville, the bête noire of all progressive Liberals. The meeting ended in an impasse and when it resumed the following evening Langlois was nominated. He presented himself as “the champion of people’s rights against the ‘trusts’ who have crushed and intimidated us,” and promised to pay particular attention to the issues of colonization and public education.

Langlois’s campaign shook the Parent administration to the core. He was elected, defeating Rainville, who ran as an independent Liberal. The Liberal party was thrown into disarray. In February 1905 Langlois supported the three cabinet ministers, Lomer Gouin, William Alexander Weir, and Adélard Turgeon, who resigned in protest against Parent’s authoritarian methods and precipitated his resignation as premier the following month.

Taking to his work as a member of the assembly with great enthusiasm, Langlois pressed the new Liberal government under Gouin to enact reforms in the field of education and in matters relating to Montreal. He would hold his seat, renamed Montreal-Saint-Louis in 1912, until 1914 and over the years some of his ideas would meet with success. He argued for a public utilities commission, proposed that a board of control be added to Montreal’s administrative structure (as he suggested, a referendum was held on the question), and lobbied for a royal commission to examine Montreal’s administration [see Lawrence John Cannon]. All these reforms were adopted.

In matters of education Langlois’s demands were wide-ranging and triggered bitter debates with Bourassa in the assembly. His focus was the unification of Catholic school boards on Montreal Island, the election of school commissioners, and the creation of a royal commission on education. Gouin ordered the creation of the royal commission with respect to the Catholic schools of Montreal in July 1909, chaired by Raoul Dandurand*.

At the same time, Langlois’s idea of liberalism moved considerably to the left in Le Canada. A convinced francophile, he turned to France for inspiration in rethinking Canadian liberalism. French liberalism at the time was taken by the idea of solidarisme, a blend of beliefs in capitalism and a limited welfare state that gave pride of place to educational reform. Langlois’s thinking strongly resembled that ideology. “The beaten path was repugnant to him,” remembered Robillard. “He ventured in new, audacious directions, at the risk of frightening important groups of the party he wanted to serve.”

Langlois’s constant criticism of Quebec’s church-dominated educational system irritated Archbishop Paul Bruchési*, who repeatedly made his views known to Laurier. Coincidentally, the leadership of the Liberal party grew exasperated with Langlois’s divisive activities at the provincial and municipal levels. “[Le Canada] has ceased to be the organ of the party in Ottawa and in Quebec; it has become . . . the organ of Langlois,” a resentful Béïque told Laurier in 1909. Laurier concurred, but confided to Béïque his “hesitation to break with the radical group of our party.”

An agreement was finally reached on Christmas Eve 1909 and Langlois was removed as editor of Le Canada a week later. He was named secretary to the International Joint Commission [see Sir George Christie Gibbons*], a position he never formally assumed. Instead, he founded a new weekly to encourage educational and municipal reform. Just as Bourassa launched Le Devoir in mid January 1910, Langlois’s Le Pays, named after the old Rouge journal, hit the stands.

Langlois was bitterly disillusioned with the party leadership and had come to the conclusion that radical action was necessary; stop-gap measures and piecemeal reforms only threatened real change. Le Pays was a last-ditch attempt to reaffirm principles most held to be lost. It proved to be both a continuation of and a new departure from his ideas of Liberal progressivism as they had been expressed in Le Canada. He embraced the trade union movement as never before and demanded open discussion of socialism. He rejected the authority of the church and denounced nationalism as an artificial fabrication of reactionaries. He was open to the suggestion that liberalism had much to learn from other ideologies and diligently applied himself and his readers to a study of the alternatives. His conclusions were, in the end, predictable: to survive, liberalism had to be radical.

On 29 Sept. 1913 Archbishop Bruchési officially barred Catholics from reading Le Pays. The paper’s response, “Toujours debout,” encapsulated the essence of Langlois’s thought and was issued as a pamphlet in English and in French. Langlois attacked the hegemony of clerico-nationalistic thinking and, mocking Bruchési’s words, boldly continued to publish Le Pays.

Relations were tense between Gouin and Langlois as Gouin tried to distance the inveterate radical. The occasion finally arose when the Quebec government decided to open an office in Brussels to encourage trade with French-speaking countries and Langlois sought the opportunity to represent the province. On 14 May 1914 his appointment as Quebec’s agent general in Brussels at a salary of $6,000 per year was confirmed. He quit Le Pays and resigned his seat in the legislature. On 22 June the Club Canadien offered a banquet in his honour. He left Montreal with his family soon after.

Europe was slowly being engulfed in war, so Langlois made arrangements with the Quebec government to settle in Paris for a time. Contacts between him and Quebec were minimal at least until 1917. Putting old differences aside, Laurier asked Langlois that November to represent the opposition in the monitoring of the Canadian election overseas. Langlois accepted. He formally assumed his position as Quebec’s agent general in Brussels in 1919 and only returned to Canada in 1921 for a brief visit.

At the end of 1927 Langlois became ill and he died of cirrhosis of the liver just over three months later in Brussels. A year earlier he had revised his will and reaffirmed his renunciation of Catholicism by asking to be cremated. His wish was not granted. His remains were transported back to Canada, a funeral mass was sung in the church at Sainte-Scholastique, and he was buried in its cemetery.

Godfroy Langlois was one of the most important journalists of his generation and one of the most progressive thinkers in the Liberal party in Quebec. A free-thinker par excellence, he worked and argued for a better democracy that would welcome new ideas. His campaign for reform in municipal government and education and against hydroelectric trusts placed him in the forefront of a small but influential group of activists who believed that Quebec’s future could be guaranteed only by energetic state involvement in key issues.

[Godfroy Langlois published a few pamphlets outlining various aspects of his thought: La république de 1848 (Montréal, 1897); Sus au Sénat ([Montréal], 1898); L’uniformité des livres: deux discours . . . ([Québec?, 1908?]); and Toujours debout: le mandement de Mgr Bruchési et la réponse du “Pays” (Montréal, 1913), translated as Still on deck: the answer of “Le Pays” to Archbishop Bruchesi’s mandement (Montreal, 1913).

This biography is based on the author’s study Devil’s advocate: Godfroy Langlois and the politics of Liberal progressivism in Laurier’s Quebec (Montreal and Toronto, 1994), translated as L’avocat du diable: Godfroy Langlois et la politique du libéralisme progressiste à l’époque de Laurier, Madeleine Hébert, trad. (Montréal, 1995). p.a.d.] ANQ-M, CE606-S22, 30 déc. 1866. Charles Robillard, “Réminiscences d’un vieux journaliste; Galerie nationale: Godfroy Langlois,” La Patrie (Montréal), 10 janv. 1943.

Cite This Article

Patrice A. Dutil, “LANGLOIS, GODFROY (baptized Joseph-Ernest-Godefroi),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 8, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/langlois_godfroy_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/langlois_godfroy_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | Patrice A. Dutil |

| Title of Article: | LANGLOIS, GODFROY (baptized Joseph-Ernest-Godefroi) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2005 |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | February 8, 2026 |