Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

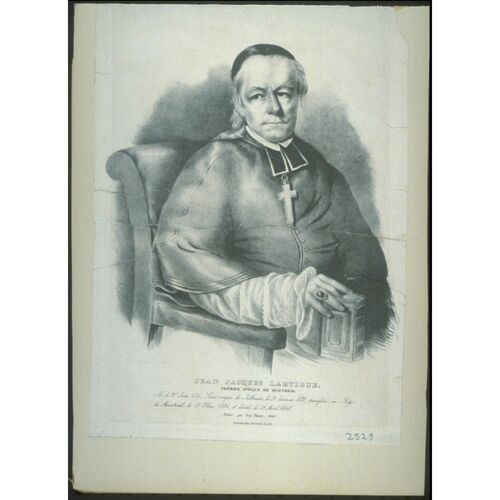

LARTIGUE, JEAN-JACQUES, Roman Catholic priest, Sulpician, and bishop; b. 20 June 1777 in Montreal, son of Jacques Larthigue, a surgeon, and Marie-Charlotte Cherrier; d. there 19 April 1840.

An only son, Jean-Jacques Lartigue belonged to a noted Montreal family. Shortly before 1757 his father, who was from Miradoux, France, had accompanied regular troops to New France as a surgeon. His mother, who came from Longueuil, was the daughter of François-Pierre Cherrier*, a merchant and notary at Longueuil and then at Saint-Denis on the Richelieu. By 1784 Lartigue was enrolled in the preparatory class at the Collège Saint-Raphaël (from 1806 the Petit Séminaire de Montréal), where he proved studious and brilliant. Upon completing the final two years of the classical program (Philosophy), he began in September 1793 to attend the English school run by the Sulpicians, and he then articled for three years with Montreal lawyers Louis-Charles Foucher and Joseph Bédard. With his cousin Denis-Benjamin Viger*, Lartigue developed an abiding interest in Lower Canadian politics, following the example of his uncles Joseph Papineau, Denis Viger*, and Benjamin-Hyacinthe-Martin Cherrier, who were members of the House of Assembly.

In 1797 Lartigue made a decision that marked a turning-point in his life. Before being called to the bar he gave up this promising career in favour of the priesthood. “A chance and quite insignificant incident . . . an unpleasantness he experienced,” according to Bishop Charles La Rocque*, seems to have prompted his sudden decision. On 23 Sept. 1797 the bishop of Quebec, Pierre Denaut*, conferred the tonsure and minor orders upon him in the parish church of Montreal. Lartigue spent the next two years teaching at the Collège Saint-Raphaël, as was the custom at the time, while pursuing his theological studies under the Sulpicians. In September 1798 he signed a public instrument recording his irrevocable decision to enter holy orders. The bishop, in the church of Longueuil, made him a subdeacon on 30 Sept. 1798 and a deacon on 28 Oct. 1799. Denaut then appointed him his secretary, to replace Augustin Chaboillez* who had been named to the parish of Sault-au-Récollet (Montreal North).

Lartigue was ordained to the priesthood on 21 Sept. 1800 at Saint-Denis on the Richelieu, in the presence of his uncle François Cherrier*, who was the local curé, his mother, and numerous other relatives. Despite his delicate health, he showed himself full of energy in adding to his responsibilities the duties of assistant priest at Longueuil, where the bishop continued to be curé. As secretary Lartigue carried out several important tasks, reshaping the Quebec ritual for instance, and he often accompanied Denaut on pastoral visits. The most arduous of these visits was made in 1803 to the Maritimes, in the far reaches of the diocese where no bishop had gone for 117 years. Exhausted and seriously ill, Lartigue almost died at Miramichi, N.B. He also was actively engaged in the administration of the diocese. In the absence of coadjutor Joseph-Octave Plessis*, who lived at Quebec, he proved a judicious adviser at a time when the Canadian church was under heavy attack from Lieutenant Governor Sir Robert Shore Milnes and his close associates Jonathan Sewell, Herman Witsius Ryland, and Jacob Mountain*.

Bishop Denaut’s death on 17 Jan. 1806 enabled Lartigue to realize a long-cherished dream of becoming a Sulpician. The prospect of a “calmer, more solitary, more contemplative life” and a more intensely intellectual one appealed to him. On 22 Feb. 1806 he left the presbytery in Longueuil and rejoined his former teachers, having been admitted as a member of the community a week before. He was the first Canadian to be received into the Séminaire de Saint-Sulpice since the coming in 1793 of the French Sulpician emigrés.

On his arrival at the seminary Lartigue was attached to ministry in the parish, being responsible for one of its four sections. He also became in turn bursar and archivist and devoted himself to various intellectual activities, such as drawing up “schedules of ceremonies” for the parish and preparing a French edition of the New Testament. The latter project, valued by Plessis, now bishop of Quebec, because of his concern about the expansion of Protestant organizations in the province, would occupy much of Lartigue’s time, especially in 1818–19, when for several months he gave it priority.

In 1806 Plessis had enlisted Lartigue to refute Attorney General Sewell’s argument in the legal proceedings that curé Joseph-Laurent Bertrand* had instituted against his parishioner Pierre Lavergne, a dispute that involved the legality of the creation of new parishes. In July 1812 the superior of the Séminaire de Saint-Sulpice, Jean-Henry-Auguste Roux*, entrusted Lartigue with the delicate task of securing obedience from the inhabitants of the Pointe-Claire and Lachine regions who had demonstrated violently against conscription. Three years later Plessis invited him to write a new catechism, but he did not feel qualified to do so. On six occasions between 1814 and 1819 he accompanied Bishop Bernard-Claude Panet*, the coadjutor, on his pastoral visits in the Montreal region.

No mission, however, would be as important as the one to the British government that Lartigue undertook in 1819 at Roux’s request. The title-deeds held by the Séminaire de Saint-Sulpice to the seigneuries of Île-de-Montréal, Lac-des-Deux-Montagnes, and Saint-Sulpice had long been contested by both the civil authorities and some well-known jurists. In the spring of 1819 the matter had been brought up again in the Legislative Council. There was more real prospect than ever that Saint-Sulpice would be despoiled of its property. Concerned that the governor, the Duke of Richmond [Lennox*], had serious doubts about the legality of the seminary’s title-deeds, Roux decided to take the case to the British authorities in London. The timing was especially appropriate since Plessis was preparing to go there to ask for letters patent for the Séminaire de Nicolet and obtain permission to divide his diocese, which was much too large. The presence of Plessis was sure to facilitate the task of Saint-Sulpice’s emissary. The superior chose Lartigue as being particularly qualified for the mission because of his knowledge of the law and mastery of English. On 3 July 1819 he sailed on the George Symes with Plessis and his secretary Pierre-Flavien Turgeon*.

Lartigue arrived in London on 14 August and with the help of Plessis immediately addressed himself to pleading the seminary’s case. He met with indifference from officials and repeated rebuffs from Colonial Secretary Lord Bathurst, who, besides being prejudiced against him, was waiting for a report from the officers of the crown before reaching a decision. Lartigue’s approaches to the former governor-in-chief of British North America, Sir John Coape Sherbrooke*, the vicar apostolic in London, William Poynter, the French ambassador to Great Britain, the Marquis de Latour-Maubourg, and some eminent London lawyers produced no results. During his stay in Paris from 23 October till 29 November he also failed to persuade the French authorities to intervene with the British government. When he left London on 6 June 1820 to return to Montreal, the seminary’s case was really no further ahead. Yet his presence had not been vain. The British authorities had given up for the time being the idea of seizing the property of Saint-Sulpice. Lartigue could not know that he had indeed prepared the ground for the accord that would be reached 20 years later to the advantage of the seminary.

When he went to London to defend the seminary’s interests, Lartigue was entirely unaware of Plessis’s intentions for him. Having failed to secure permission to divide the diocese of Quebec, Plessis had obtained the government’s agreement to recognize four auxiliary bishops as his representatives in Upper Canada, the northwest, the Maritimes, and the district of Montreal. On 17 Sept. 1819 Lartigue learned that the archbishop had him in mind for the Montreal post. Although reluctant at first to accede to Plessis’s wishes, he finally replied affirmatively, but on condition that his superiors assented. Antoine de Pouget Duclaux, superior general of Saint-Sulpice in Paris, left the decision to Lartigue’s immediate superior, Roux, who gave an evasive reply in December 1819. Lartigue’s fears were confirmed: Roux apparently would consent to his becoming a bishop if he left the seminary. In March 1820 Lartigue received apostolic letters naming him bishop of Telmessus in Lycia, as well as auxiliary and suffragan to Plessis. For Lartigue, who was obliged by papal order to accept the office a short time later, a new life was beginning. He would no longer be a Sulpician, but auxiliary bishop in Montreal. Jean-Baptiste Thavenet had perhaps been a better prophet than he realized when he observed not long before: “One more word about the episcopate being offered you. It reminds me of the regional bishops of Rome in the 5th century: you would be bishop, not of Montreal but in Montreal. You would be the bishop’s vicar there, and the vicar general would no longer be anything, etc. And if you were not a member of the seminary (as would inevitably happen), what a sad existence for you!”

Lartigue was consecrated bishop on 21 Jan. 1821 in the church of Notre-Dame in Montreal. He became responsible for the largest district in Lower Canada. Bounded on the northeast by the Trois-Rivières region, on the south by Vermont and New York, and on the southwest by Upper Canada, the district of Montreal had nearly 200,000 inhabitants, 170,000 of them Catholics spread out over 72 parishes and missions. Almost nine-tenths of Montreal’s 18,767 inhabitants belonged to the Roman Catholic Church. There were many religious establishments and they were thriving. Besides the Séminaire de Saint-Sulpice and the church of Notre-Dame, the town had the Petit Séminaire, the Recollet chapel, and the chapel of Notre-Dame-de-Bonsecours, a convent for girls run by the Sisters of the Congregation of Notre-Dame, and two hospitals, the Hôtel-Dieu and the Hôpital Général.

Several important tasks awaited the new bishop. The theological and spiritual training of the clergy was distinctly inadequate at the time, a situation Lartigue wanted to remedy quickly. In 1825 he established at the recently opened bishop’s palace a theological school, the Séminaire Saint-Jacques, which under the direction of his secretary and right-hand man, Ignace Bourget*, quickly became a nursery of ultramontanism. Papal infallibility would be taught there 40 years before a Vatican council proclaimed the dogma. At a period when there were violent clashes between gallicans and ultramontanes in France, Lartigue regarded the church as a body with a strongly hierarchical organization untouched by democratic concepts of power and subject in all things to papal authority. The absolute primacy of the sovereign pontiff was the key element in this definition. “Pastor to the pastors” and endowed with infallibility quite apart from the bishops’ assent, the pope by divine right had “pastoral jurisdiction over all the bishops in the world,” whom he could move or remove as he wished.

This concept of the church and this love for the person of its head came to Lartigue partly from his respect for Hugues-Félicité-Robert de La Mennais, whose Essai sur l’indifférence en matière de religion (Paris, 1817) he had eagerly read at the time of his trip to Europe. From 1820 Lartigue had assiduously absorbed the writings of Joseph de Maistre, Philippe-Olympe Gerbet, and La Mennais, which he received regularly through Parisian bookseller Martin Bossange. As a subscriber to several Lamennaisian periodicals, including Le Drapeau blanc, Le Mémorial catholique, and L’Avenir, he developed an unbounded admiration for La Mennais, as a “superior writer and thorough papist” who made people “love religion and its visible head on earth.” Sick at heart, he would learn of the denunciation and then of the condemnation by Pope Gregory XVI’s encyclicals in 1832 and 1834 of the man whose system of philosophy and, even more, whose ultramontanism he would never repudiate.

To Lartigue the task of ensuring greater cohesion and stability in the Canadian church seemed just as important. Consequently he worked to get improvement of the legislation concerning civil recognition of the parishes and the right of religious corporations and communities to own and acquire landed property. In addition he fully supported Plessis’s plan to regroup all the dioceses in British North America. After the bishop’s death, Lartigue took the initiative himself, with the result that the plan was carried out in 1844, when the ecclesiastical province of Quebec was established as the first one in Canada.

Imbued with the idea of the supremacy of the church over secular society, Lartigue was no less concerned with the development of the Christian faith and understanding of the Catholics in his diocese. He demanded their absolute obedience to the rules of conduct laid down by the bishops and counted on their action to preserve the prerogatives of the church and ensure its influence upon society. To achieve these ends he wanted to set up a religious press run by the episcopal authorities to “shape and control public opinion” and direct it to the benefit of the church. His successor, Bishop Bourget, would achieve this aim in 1841 with the publication in Montreal of Mélanges religieux [see Jean-Charles Prince*].

The same concern led Lartigue to take a keen interest in education. He maintained that teaching was essentially a responsibility of the church, not the state, and he advocated a school system independent of the Royal Institution for the Advancement of Learning [see Joseph Langley Mills*] but connected with the parishes; in 1824, at the time the fabrique schools act was passed, he expressed a wish that the clergy take as much advantage of the legislation as possible. It authorized parish priests and churchwardens to acquire funds and to devote part of the income of the fabriques to establishing elementary schools. Lartigue had not waited to set an example. Upon taking up residence in the new bishop’s palace he had opened a free school which by 1826 had nearly 80 boys and girls. A short time later he established a second school in a house bought for the purpose; he entrusted its management to the Association des Dames Bienveillantes de Saint-Jacques, an organization founded in July 1828 to educate girls from poor families. He showed constant solicitude for the Collège de Saint-Hyacinthe [see Antoine Girouard*], which was under his jurisdiction from 1824 and which, under the direction of Jean-Charles Prince, became in effect a “Lamennaisian college.”

Lartigue was also involved in social concerns. In 1827 he strongly encouraged the founding of the Association des Dames de la Charité, a lay benevolent society to help the poor in Montreal [see Marie-Amable Foretier*]. When in the summer of 1832 a terrible cholera epidemic struck the town, he supported the association’s plan to open an orphanage for the children of immigrants, mostly Irish, who had died of the disease. Lartigue was the spiritual adviser of Émilie Tavernier*, one of the most active members of the association, and it was at his suggestion that she had founded a refuge for frail or sick elderly women in 1830. In addition, Lartigue and the Canadian Sulpician Nicolas Dufresne* had helped Agathe-Henriette Huguet, dit Latour, in 1829 to establish the Charitable Institution for Female Penitents.

Yet these achievements came in the course of a particularly agitated episcopate, one that was marked by incessant struggle, either with the Séminaire de Saint-Sulpice in Montreal, or the British authorities, or the new secular Canadian leaders. In 1837 Lartigue recalled his years as bishop with resentment: his life had been “strewn with the vicissitudes of temporal affairs, and almost equally composed of happy events and adversities.” Many a time he begged Bishop Plessis and his successors to “withdraw [him] at last from this wretched life,” offering his resignation on several occasions to the authorities in Rome.

The first 15 years of Lartigue’s episcopate were marked by a confrontation with the Séminaire de Saint-Sulpice. It began with the bishop’s decision in January 1821 to reside in Montreal rather than in a parish on the south shore of the St Lawrence, as it is thought that Roux wished. Roux was firmly convinced that in deciding “to raise one of their colleagues to the episcopacy” Plessis had sought to “introduce a Canadian bishop into the seminary” to diminish the influence of the French Sulpicians and bring the institution under his control. This conviction explains Lartigue’s exclusion from the seminary in February 1821, when he was forced to seek shelter at the Hôtel-Dieu of Montreal, as well as the astonishing removal of the episcopal throne from the parish church of Notre-Dame by the churchwardens in July during Lartigue’s absence. It also explains their decision in September 1822 to build a new church [see James O’Donnell*], probably to thwart Lartigue’s plan in building the church of Saint-Jacques.

It was inevitable that there would be conflict between the auxiliary bishop and the Sulpicians, who since their arrival in 1657 had always exercised a strong hold on Montreal. Lartigue had thought that by taking care to consult his Sulpician superiors and by insisting upon an order from the pope to accept episcopal office, he would overcome his colleagues’ reservations. In reality, Roux did not want a Canadian bishop in Montreal, even a Sulpician one, lest the exclusively French character of the seminary be changed; rarely does decolonization proceed smoothly.

Lartigue consequently rebuked the Sulpicians for trying in both Rome and London to ensure that they could recruit men of French origin, denounced the policy of discrimination against the Canadian Sulpicians within the community, and in 1833 energetically opposed the seminary’s efforts to get a French Sulpician appointed apostolic prefect in Montreal. Lartigue did not believe in “a devious policy [designed] to handle every question gently” which “ended up spoiling everything.” Had he received more support from Plessis he would surely have reminded the Sulpicians more vigorously that they could not constitute a church within the church and would have dealt more severely with recalcitrant parish priests such as Augustin Chaboillez, Jean-Baptiste Saint-Germain*, and François-Xavier Pigeon who were partisans of Saint-Sulpice

In 1835, however, a rapprochement between Lartigue and the seminary began. By August Lartigue was ready to choose a successor for himself who would be “acceptable to Saint-Sulpice.” Indeed, the illness and sudden death in May of Pierre-Antoine Tabeau*, who was to have succeeded him, had given him much cause for reflection. The celebration on 24 Sept. 1835 of French Sulpician Jacques-Guillaume Roque’s jubilee in the priesthood, which took place in the bishop’s presence, sealed this reconciliation. From then on the greatest harmony reigned. In December 1836 Lartigue wrote to the superior, Joseph-Vincent Quiblier*, with obvious joy: “I can assure you that I have gladly forgotten all that has happened over fifteen years, and think only of cherishing and favouring your house.” The following year the superior general of Saint-Sulpice in Paris, Antoine Garnier, entrusted the seminary to the bishop’s protection and benevolent attention.

Among the aims that were pursued unflaggingly by Lartigue during his episcopate the complete independence of the church must receive the greatest emphasis. Maintaining that the Canadian church was independent of the political authority and refusing to be regarded “simply as a tool in the hands of the executive,” he energetically opposed the British authorities, who had no need to subjugate the church or dictate a line of conduct to religious leaders. Unlike bishops Plessis, Panet, and Joseph Signay, who thought that the liberty of the church depended upon their obedience to Britain’s instructions, Lartigue had realized that, in a country where representative institutions existed, the church did not have to seek the protection of politicians; it enjoyed an autonomous power by virtue of the authority it exercised over the faithful, who were also electors. Eager for the freedom of action enjoyed by Bishop Benoît-Joseph Flaget, his colleague in Bardstown, Ky, Lartigue knew that with a touchy and disputatious Protestant government the only policy to pursue was that of the fait accompli. He adopted it at the time the diocese of Montreal was created when, in Marcel Trudel’s words, he had “the courage to make the first gesture of absolute independence.” He insisted to Bishop Joseph-Norbert Provencher*, a colleague from the northwest visiting Rome in October 1835, that the authorities in Rome should attach no importance “to the British government’s consent to or approval of such an arrangement,” and in November, without the knowledge of Governor Lord Gosford [Acheson], he sent to the pope the Montreal clergy’s request for an episcopal see at Montreal.

This bold policy bore fruit. On 13 May 1836 Pope Gregory XVI signed the bull creating the new diocese of Montreal and the brief appointing Lartigue to it. As Lartigue had foreseen, when London found itself faced with the fait accompli, it accepted the new bishop, the colonial secretary giving his consent on 26 May. The bishop of Montreal took possession of his see on 8 September amid general enthusiasm. A short time later Lartigue made a second gesture that was no less decisive: he handled the matter of his coadjutor with Rome without prior discussion with the governor, indeed, without even a mention of it. A new era had dawned in the relations between the Canadian church and the state. The British authorities would intervene less and less in the internal affairs of the church, the appointment of bishops, and the establishment of new dioceses. The bishop of Montreal had shown his colleagues and successors the way. This major step forward would be confirmed in 1849 under responsible government, when the church would become independent of the state.

Another matter brought Lartigue into conflict with the leaders in the House of Assembly, in particular his cousin Louis-Joseph Papineau*. When in 1791 parliamentary institutions had been put into place in Lower Canada, the new spokesmen for the Canadian community soon aroused the distrust of the ecclesiastical authorities. The latter did not easily accept being supplanted by leaders who, if not hostile to the church, were at least not much inclined to accept their instructions. Nevertheless, although their official policy was one of non-intervention, the representatives of the church unquestionably supported the Canadians’ cause. For his part Lartigue, who was deeply affected by the injustices inflicted upon his compatriots, always displayed a keen interest in the struggles of the political leaders and the aims they pursued. His correspondence with his cousin Denis-Benjamin Viger, Papineau’s right-hand man, furnishes eloquent proof of this interest, particularly in 1822, when a bill to unite the two Canadas was presented to the British parliament, and in 1828, at the time of a mission to London by Viger, Austin Cuvillier, and John Neilson. In 1827 he justified the non-interventionist policy of the clergy that he had consistently advocated: “It is important for [the Canadians] that at this juncture we not pique the government, which in reacting might unwittingly do religion much harm . . . ; moreover, without our creating a disturbance the government in England will know of our true feelings and will discern what we are thinking despite our silence if it sees the masses, upon whom we have a great influence, as it knows, complaining with virtually one voice against the administration.”

From 1829, however, relations between the Patriote party and the bishops deteriorated rapidly. Taking issue with the aims pursued by the leaders of the assembly, particularly in the schools act of 1829 and the 1831 bill on fabriques [see Louis Bourdages*], in which could be sensed the influence of 18th-century French deistic liberalism and a strong democratic tendency, Lartigue led a counter offensive; it would defeat the liberals’ attempts to limit the influence of the church upon the people and to define Canadian society in terms other than its religious affiliation. Worried by the rise of an increasingly aggressive and demanding Canadian nationalism and by the clearly revolutionary tone of the radical political leaders, who scarcely inspired confidence in him, in the end he utterly opposed them. He noticed with alarm that the movement to emancipate the Canadians was going ahead without the church, indeed was proceeding against it, and that the small degree of freedom the Canadian church had managed to obtain was threatened by both the British government and the Canadian politicians themselves. The test of strength between the two forces came in 1837. On 24 October, in a pastoral letter to his diocese, the bishop of Montreal condemned the action of the Patriote leaders, basing his argument on a biblical doctrine that legitimate civil authorities held power from God. At the same time, along with the moderate wing of the Patriote party he cast serious doubt on the wisdom and validity of the radicals’ policy, which he considered as imprudent as it was harmful. The divorce between church and assembly first evident six years earlier was complete.

Events vindicated Lartigue. After suffering defeat at Saint-Charles-sur-Richelieu and then at Saint-Eustache, the Patriotes lost faith in their leaders, particularly when they were abandoned by several. Despite the unfavourable reactions at first provoked by his intervention, even within a section of the clergy, Lartigue soon appeared as a true leader, independent, lucid, anxious to merit his compatriots’ confidence and capable of proposing to them a more realistic program than that of the Patriote leaders. Two developments convinced the Canadians of the selflessness of Lartigue and their other religious leaders, who had rallied around him. On 9 Nov. 1837, at the request of the parish priests from the Richelieu valley, he endorsed a petition for the rights of Canadians that all the priests in Lower Canada signed. As well, he and his coadjutor brought support to the unfortunate victims who were filling the prisons, particularly after the abortive uprising on the night of 3–4 Nov. 1838. Meanwhile, late in January 1838 Lartigue had interceded with Lord Gosford to get the government in London to agree not to alter the constitution of Lower Canada or impose union of the two Canadas, as the faction supporting union from 1822 ardently desired. When in the spring of 1839 word came of the recommendations in the report by Lord Durham [Lambton], which were designed to “anglify” and “decatholicize” the Canadians by a legislative union and a system of non-denominational schools, Lartigue encouraged his clergy to sign a new petition to the queen, the House of Lords, and the Commons in order to oppose the plan.

At this decisive moment in the history of French Canada, when the Canadians found themselves abandoned, even misled by their political leaders, the religious leaders had stepped in and put themselves at the service of the nation. The Canadian church thereupon regained the authority it had exercised over the Canadian collectivity before the introduction of parliamentary institutions. Thenceforth it constituted a political force with which the new Canadian leaders, more moderate and more reasonable, would have to reckon.

Lartigue, who had been ill for a number of years, died on 19 April 1840. The press, Le Canadien in particular, unanimously stressed the greatness of his episcopate. More than 10,000 people attended his funeral in the church of Notre-Dame on 22 April. As many more were present the next day in the cathedral of Saint-Jacques to hear Bishop Bourget pay him a final tribute. With the death of the first bishop of Montreal the Catholic and ultramontane reaction, of which he had been the chief architect, was irretrievably under way. Bourget, his successor, who had been steered in this direction by a preparation spanning 16 years as a secretary and 3 years as a bishop with Lartigue, would continue his work.

Detailed bibliographies for Jean-Jacques Lartigue and the period 1777–1840 may be found in Chaussé, Jean-Jacques Lartigue, and Lemieux, L’établissement de la première prov. eccl.

AAQ, 1 CB, VI–VIII; 26 CP, I–VII. ACAM, 255.109; 295.101, .103; 465.101; 583.000; 780.034; 901.012–18, .021–25, .028–29, .033, .037, .039, .041, .047, .050, .136–37, .150; RLL, I–III. Arch. de la Compagnie de Jésus, prov. du Canada français (Saint-Jérôme, Qué.), 2196, 3182–83. Arch. du séminaire de Saint-Sulpice (Paris), Fonds canadien, dossiers 22, 27–29, 52, 55, 59, 63, 67, 73–76, 79–89, 94, 98–99. ASQ, Fonds Viger-Verreau, sér.O, 0128. ASSM, 1bis; 21; 24, B; 27. PAC, MG 24, B2, 1, 2, 16–21; B6, 1–12; B46; J15. Allaire, Dictionnaire. F.-M. Bibaud, Dict. hist.; Le panthéon canadien (A. et V. Bibaud; 1891). Desrosiers, “Inv. de la corr. de Mgr Lartigue,” ANQ Rapport, 1941–42, 1942–43, 1943–44, 1944–45, 1945–46. G.-É. Giguère, “La restauration de la Compagnie de Jésus au Canada, 1839–1857” (thèse de phd, 2v., univ. de Montréal, 1965). J.-P. Langlois, “L’ecclésiologie mise en œuvre par Mgr Lartigue (relations église-état) durant les troubles de 1837–1838” (thèse de ll, univ. de Montréal, 1976). Anne McDermaid, “Bishop Lartigue and the first rebellion in the Montreal area” (ma thesis, Carleton Univ., Ottawa, 1967). Yvette Majerus, “L’éducation dans le diocèse de Montréal d’après la correspondance de ses deux premiers évêques, Mgr J.-J. Lartigue et Mgr I. Bourget, de 1820 à 1967” (thèse de phd, McGill Univ., Montréal, 1971). Léon Pouliot, Mgr Bourget et son temps, vol.1; Trois grands artisans du diocèse de Montréal (Montréal, 1936). L.-P. Tardif, “Le nationalisme religieux de Mgr Lartigue” (thèse de ll, univ. Laval, Québec, 1956). E.-J. [-A.] Auclair, “Le premier évêque de Montréal, Mgr Lartigue,” CCHA Rapport, 12 (1944–45): 111–19. François Beaudin, “L’influence de La Mennais sur Mgr Lartigue, premier évêque de Montréal,” RHAF, 25 (1971–72): 225–37. J.-H. Charland, “Mgr Jean-Jacques Lartigue, 1er évêque de Montréal (1777–1840),” Rev. canadienne, 23 (1887): 579–82.

Cite This Article

Gilles Chaussé and Lucien Lemieux, “LARTIGUE, JEAN-JACQUES,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 7, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 10, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/lartigue_jean_jacques_7E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/lartigue_jean_jacques_7E.html |

| Author of Article: | Gilles Chaussé and Lucien Lemieux |

| Title of Article: | LARTIGUE, JEAN-JACQUES |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 7 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1988 |

| Year of revision: | 1988 |

| Access Date: | March 10, 2026 |