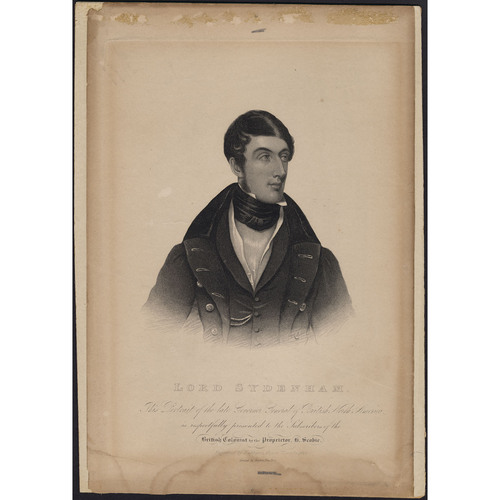

THOMSON, CHARLES EDWARD POULETT, 1st Baron SYDENHAM, colonial administrator; b. 13 Sept. 1799 at Waverley Abbey, England, third son and youngest of nine children of John Poulett Thomson and Charlotte Jacob; d. unmarried 19 Sept. 1841 in Kingston, Upper Canada.

Charles Edward Poulett Thomson’s father was a partner in J. Thomson, T. Bonar and Company of London and St Petersburg, Russia, for several generations a principal merchant house in the Russian-Baltic trade. After attending private schools until age 16, Thomson entered the family firm at St Petersburg. In 1817 he came home because of poor health and embarked on a prolonged tour of southern Europe. Following a stint in the firm’s London office he returned to Russia in 1821 and over the next three years travelled extensively in eastern Europe. He established permanent residence in London in 1824 but frequently visited the Continent, especially Paris.

As “the youngest and prettiest child of the family,” according to a brother, George Julius Poulett Scrope (Thomson), Thomson had been “the spoilt pet of all” and early evinced self-confidence and ambition. The diarist Charles Cavendish Fulke Greville described him as “the greatest coxcomb I ever saw, and the vainest dog.” Certainly Thomson aped the manners of the aristocracy. His “love of great society” earned him the censure of his fellow merchants and members of his own family. Single, chiefly – his brother claimed – because he was in failing health and incessantly occupied, he was known as a sensualist. In the Canadas his establishment would, in the words of the author John Richardson*, “acknowledge . . . the sway of at least one mistress.” Married or single, all women “excited his homage,” but the “attentions” he devoted to a married woman in Toronto, Richardson recorded, “were so very marked, that the scandalous circles rang with them.” He was also a gourmet who would try to introduce “French cookery” in the colonies.

Thomson was not content with the career marked out for him, and he was not a particularly successful businessman. In 1825 he was saved from disaster in a speculative venture only by the caution of an elder brother, Andrew Henry. Although fluent in French, German, Russian, and Italian, Thomson was barred from the foreign service, which was staffed by the great landed families. Nor was he sufficiently wealthy to buy his way into the aristocracy. Through his early support for parliamentary reform and liberal measures such as the ballot and the abolition of the corn laws, Thomson would reveal the resentment and frustration engendered by his uncertain status in the aristocratic society he frequented.

An early advocate of free trade, Thomson naturally became a friend of the Benthamites and was elected to the Political Economy Club. In 1825 Joseph Hume helped him secure the liberal nomination in Dover, and Jeremy Bentham canvassed for him during the election of May 1826. Thomson won, but only at great financial cost, and his election angered his family, who opposed his liberal views. In the House of Commons, according to one critic, Thomson was looked upon as a “bore”; his voice was “thin and effeminate” and his personal appearance “characteristic of a barber’s apprentice.” He rarely spoke on the “exciting party questions of the day,” his brother Scrope noted, and his speeches on commercial matters were considered dogmatic. None the less, Thomson found an important aristocratic patron in John Charles Spencer, Viscount Althorp, who became chancellor of the Exchequer in the Whig administration formed in late 1830; he secured for Thomson the posts of vice-president of the Board of Trade and treasurer of the navy. Since Thomson’s superior at the board, Lord Auckland, was a relative nonentity, Thomson conducted its business. Working closely with Althorp, he helped draft the abortive free trade budget of 1831, thus incurring the undying enmity of protectionists and completely alienating his family. His views were, however, popular with the manufacturing interests in the north of England; although returned for Dover in 1830, 1831, and 1832, he transferred to Manchester, where he was elected without campaigning in 1832 and re-elected in 1834 and 1837. From June until November 1834 and again in the Whig administration formed in April 1835, Thomson served as president of the Board of Trade, opening the department to free traders, making numerous minor reductions in customs regulations, and negotiating trade agreements with several European governments. Thomson expanded the responsibilities of the board and exercised a new control over private bills, especially railway and bank charters; when he sought to exert his authority to supervise colonial legislation, he plunged the Colonial Office into a bitter dispute with the Upper Canadian House of Assembly over currency and banking legislation.

In general, Thomson was not directly involved in formulating the cabinet’s response to the political crisis in the Canadas. When news of the rebellions there reached London, he was, according to Lord Howick, “all for executions.” Although once close to Lord Durham [Lambton], he was unsympathetic when Durham resigned after the cabinet failed to defend his ordinance exiling rebels to Bermuda; initially he apparently did not view the Durham report with much enthusiasm. In mid March 1839 he served on the cabinet committee that adopted a proposal for a federal union of the Canadas recommended by Edward Ellice*. After that scheme was abandoned, however, he voted with a slim majority in favour of a legislative union along the lines suggested by Durham.

Thomson became increasingly disillusioned with his position in the government, especially when passed over for the chancellorship of the Exchequer in early 1839. His chief complaint, however, was the cabinet’s failure to adopt a major change in economic policy. The conventional Whig approach to finance had left the government virtually bankrupt, and Thomson knew that reforms were necessary. He also knew that he could not persuade the Commons to adopt them and consequently, when finally offered the Exchequer in the summer of 1839, he declined. On 6 September, over the opposition of timber merchants, he was commissioned governor-in-chief of British North America. The Canadian rebels, he predicted, “can’t be more unreasonable than the ultras on both sides of the House of Commons.” He insisted upon the unusually high salary of £7,000, an outfit of £3,000, and substantial casual expenses, and he received the pledge of a peerage if he was successful in his administration.

Before departing Thomson met with Durham and received his blessing. Thomson’s primary goal was to get the support of the Canadians for a union acceptable to the British government, and to persuade them of the benefits of union he carried with him the promise of an imperial guarantee for a large loan. He landed at Quebec on 19 Oct. 1839 and took over the administration of Lower Canada from Sir John Colborne*. Thomson was aware that his appointment was viewed with dismay by colonial merchants. The Pictou Observer of Nova Scotia described him as a “selfish, prejudiced Russian timber merchant” and wished him “a good sousing in his favourite Baltic tar, with such a supply of feathers as may fortify him against the natural and political winter he has to encounter.” Yet, after his first levee, on 21 October, Thomson claimed that his reception, even among the Quebec merchants, had been “certainly good.”

On 23 October Thomson settled in Montreal and reported that, although the province was “quiet,” only the power of the government kept French Canadians from “acts of insubordination.” To discourage disaffection he refused to release from prison the Patriote leader Denis-Benjamin Viger* and had Augustin-Norbert Morin* arrested; he was, however, forced to release Morin because the original warrant for high treason lacked supporting testimony. On 11 November Thomson convened the Special Council, an appointed body of men of proven loyalty which had replaced the legislature after the rebellion of 1837. Only a rump of 15 members braved the snows to assemble in Montreal, and Thomson allowed them merely two days to debate the question of union. The terms he proposed were most unfair to Lower Canada – equal representation for the less populous Upper Canada, the charging of its higher debt against the united province, and a permanent civil list against which the Lower Canadian assembly had long fought – but only three members voted against them. Although Thomson reported that the matter of union was “over with,” John Neilson and others opposed to union raised petitions against it while the francophone press directly attacked “le poulet,” as Thomson was called.

Inevitably, Thomson reacted angrily to such attacks. “If it were possible,” he wrote in November 1839, “the best thing for Lower Canada would be a despotism for ten years more.” Even before leaving Britain, according to the London Colonial Gazette, he had been “convinced by Lord Durham’s Report, despatches, and conversation, that French ascendancy in Lower Canada is simply impossible” and had indicated that he would “uphold the principle of ascendancy for the majority with regard to all Canada.” An admirer of France and French culture, Thomson was disturbed neither by the use of French, which he spoke fluently, nor by the efforts of French Canadians to preserve their heritage. However, like Durham, he believed in the innate superiority of British institutions and felt that they could be adopted by peoples with cultural traditions other than British. Again like Durham, he thought that it was undesirable – and ultimately impossible – for French Canadians to isolate themselves in British North America; if they did, they would “grow up in their national prejudices and habits without any sympathy with their fellow Colonists.” He was particularly scornful of the habitants – “a People not incapable of improvement, but still only to be very slowly & gradually improved in their Habits & Education.” Although he blamed the Roman Catholic Church for keeping its faithful in ignorance and thus under its control, he was not anti-Catholic. He foresaw giving to that church a share of the proceeds from the clergy reserves, hitherto reserved to the Church of England, and upheld the claims of the Sulpicians to compensation for lost seigneurial rights; indeed, he admired the Sulpicians, most of whom were immigrants from France, finding in them a “reasoned, and, therefore, a steady attachment to . . . British rule, and a thorough contempt for those miserable antipathies of race which so universally prevail among the native Canadians.”

In November Thomson departed for Toronto, where he assumed control of the government of Upper Canada on the 22nd. There was considerable hostility to union among officials in the colony, particularly those resident in Toronto, and when Thomson took the oaths of office, John Macaulay* noted, he was greeted with “an abortion of a cheer which was worse than silence.” Thomson sought to dissipate opposition by meeting privately with members of the legislature, which was convened for 3 December. Within Upper Canada Durham’s report had unleashed a broadly based campaign for reform, and Thomson correctly perceived that the “foolish cry for ‘responsible Govt.’” had gained support because of Lieutenant Governor Sir George Arthur*’s “opposition to all reform and . . . his treating all those who opposed the official party as Democrats and Rebels.” Thomson denounced “any scheme which would render the power of the Governor subordinate to that of a Council,” but he had no objection to Durham’s “practical views of Colonial Government” and promised to administer local matters “in accordance with the wishes of the Legislature.” On this basis he secured the support of the reform minority in the assembly. To the conservative majority Thomson proffered assurance that union and the imperial guarantee of a loan would relieve the colony’s financial embarrassments, and with Arthur’s assistance he won over many moderates.

On 13 December Thomson’s proposals were approved in the Legislative Council, 14 to 8, over the vehement opposition of Bishop John Strachan*. In the assembly Thomson had to work through Attorney General Christopher Alexander Hagerman, who initially opposed union, and Solicitor General William Henry Draper*, who did not like Thomson’s terms. In the previous session the assembly had accepted union on condition that the seat of government be in Upper Canada, that Upper Canada receive more seats in the united legislature than Lower Canada, and that English be the only language of the legislature and courts. Although Thomson rejected conditions so “unjust and oppressive” to the French Canadians, union passed on 19 December. The conservatives continued their efforts to modify Thomson’s terms. On 13 Jan. 1840 John Solomon Cartwright embodied their demands in an address that was carried 28 to 17, and Thomson reluctantly agreed that written records would be kept in English only, that there would be a property qualification for assemblymen, and that legislative councillors would be appointed for life. However, he refused to select Toronto as the seat of government, leaving the choice of a site “to be regulated by circumstances.”

Thomson’s commitment to integrating the French Canadians into the union had led him to seek for the minority “their fair share of the representation.” The terms of union which he extracted from Upper Canada were the best he could get. The proscription of French in written documents was indefensible and ultimately unenforceable, and the equality of representation of the two Canadas was shortsighted, since Upper Canada was bound to grow more rapidly than Lower Canada. The decision to transfer the Upper Canadian debt to the United Province was also unfair, but Thomson correctly pointed out that the sums expended on “the great canals” were “of no less advantage to the Lower than to the Upper Province” and that the costs of completing the canal system would be “very trifling” in view of the long-term return on the investment.

On 23 Jan. 1840 Thomson submitted to Secretary of State Lord John Russell a draft bill apparently prepared with the assistance of Chief Justice James Stuart*. In general it sought to introduce union “with as little interference as possible” in existing institutions. It differed from a bill prepared by the Whig government the previous year, by leaving the structure of the Legislative Council unchanged, creating 76 single-member constituencies for the Legislative Assembly, imposing a £500 qualification for assemblymen, providing for publication of all records in English (although debates could be conducted in either language), and preserving the township form of municipal government in Upper Canada and extending it to Lower Canada. Thomson suggested that clauses dealing with the civil list be framed in London but insisted that it was unsafe “to leave the Government dependent on the Assembly.”

A few days later Thomson also sent home his measure to deal with “the root of all the troubles” of Upper Canada, the clergy reserves [see John Strachan]. One-half of the income from the reserves was to be divided equally between the churches of England and Scotland and the other half distributed among the other denominations on the same basis. Strachan and the “family compact” tories, as well as doctrinaire reformers, opposed Thomson’s bill, but an overwhelming majority in the assembly rallied to its support. In fact, as Thomson’s civil secretary, Thomas William Clinton Murdoch, noted, the assembly “exhibited for the first time in Canada the working of a government majority on the same principles on which the parliamentary business had been conducted in the mother country.” Although Thomson rejected the assembly’s request to see any dispatches he had received on the subject of responsible government, he had, in Murdoch’s view, “conceded the principle of responsibility as far as it had ever been demanded by the moderate reformers.” Thomson strengthened his government by raising Hagerman to the bench, replacing him with Draper, and appointing Robert Baldwin* solicitor general. In early 1840 he wooed the large Canada Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church by insisting that it, rather than the British Wesleyan Conference, receive government funds and by supporting Upper Canada Academy at Cobourg. He was rewarded with the consistent loyalty of Egerton Ryerson*’s Christian Guardian (Toronto), which Thomson described as “the only decent paper in both Canadas.” On 10 Feb. 1840 Thomson prorogued the legislature and declared to Russell that if his union and clergy reserve bills – “the Reform Bill and Irish Church of Canada” – were accepted, “I will guarantee you Upper Canada.”

Thomson was less optimistic about the prospect of reconciling French Canadians to union. On 18 February he left Toronto and in one of the most rapid journeys ever made by sleigh arrived in Montreal 36 hours later. He insisted that Lower Canada was quiet, that support for union was strong among moderates, and that Vital Têtu, a prominent merchant selected to carry anti-union petitions to London, was “a person of no importance”; yet privately he admitted to Russell that French Canadians would use representative institutions to resist any “practical measure of improvement.” He therefore shoved through the Special Council a series of bills to facilitate union: they incorporated Quebec and Montreal, reorganized the judicial system, established a more efficient police force, and provided for the gradual extinction of seigneurial dues in Montreal.

Despite a “few inaccuracies” and an insufficient civil list, Thomson affirmed that the draft of the union bill which he received from Russell in May “will do.” To ensure that French Canadian assemblymen imbibed “English Ideas” he chose Kingston as the capital of the united province, but to obtain French Canadian support he offered Louis-Hippolyte La Fontaine* the post of solicitor general, although La Fontaine declined the post. Having been pressured by Bishop Jean-Jacques Lartigue and the French Canadian élite of Montreal, Thomson released Denis-Benjamin Viger from prison in May, and in June he let lapse the suspension of habeas corpus by which means Viger had been held. When members of the English party protested compensation to the Séminaire de Saint-Sulpice for extinction of its seigneurial rights, Thomson denounced the “spirit of intolerance” shown by the British minority, and when he appointed the first corporations for Montreal and Quebec, he ensured that French Canadians were represented, albeit not equally, and selected René-Édouard Caron* as mayor of Quebec. The preference in patronage that he gave to the British of Lower Canada was in part forced on Thomson; he offered positions to French Canadians “whose loyalty is undoubted” and who accepted union as a fait accompli, such as Alexandre-Maurice Delisle* or Melchior-Alphonse de Salaberry*, but few would risk political stigma as vendus. Nevertheless, Thomson’s efforts probably played a part in persuading moderate reformers such as La Fontaine to accept union and to work within the united legislature to achieve their goals.

To his “infinite annoyance,” since he was overwhelmed with work and subject to recurring attacks of gout, with which he had been afflicted since age 30, Thomson was forced to depart on 3 July for Nova Scotia and mediate a dispute between Lieutenant Governor Sir Colin Campbell, “playing the dunce at Halifax,” and the House of Assembly. En route he spent two days in the Eastern Townships passing “under triumphal arches.” He assumed control of the government of Nova Scotia on 9 July and recommended remodelling the Executive Council to include leading members from both sides in the assembly and compelling the chief government officials to sit in that house. Even Joseph Howe* proclaimed that Thomson was advising “exactly what the friends of what is called Responsible Government would have created.” Indeed, Howe acknowledged that by including the leading public officers and heads of department in the council Thomson had made “an important refinement” to his own proposals. Ultimately Campbell’s refusal to countenance Thomson’s recommendations resulted in his replacement by Lord Falkland [Cary*].

In late July Thomson visited Prince Edward Island and met with Lieutenant Governor Sir Charles Augustus FitzRoy*. Soon after, he accompanied Lieutenant Governor Sir John Harvey* of New Brunswick on a whirlwind tour of Saint John and Fredericton and returned to Halifax full of praise for the “entire harmony” which Harvey, “the Pearl of Civil Governors” in his estimation, had established between the executive and the legislature. Later, however, he changed his view. Faced by acts of aggression from the United States, Thomson had pressured the British government into increasing substantially its garrisons in British North America and its expenditures on defensive works. In late 1840 Harvey’s indecision about the use to be made of troops sent to his command, at his own request, infuriated the more bellicose governor-in-chief, who successfully recommended Harvey’s dismissal. In April 1841 the governor insisted that the British government take an aggressive position with the United States, “whatever the consequences,” in seeking the release of Alexander McLeod*, an Upper Canadian wrongly jailed in New York State for participation in the sinking of the rebel supply ship Caroline in December 1837. By stiffening the resolve of the British government, he contributed to the satisfactory negotiation of the Webster-Ashburton Treaty of 1842.

On 19 Aug. 1840 the governor had left Montreal for the Eastern Townships and Upper Canada, visiting more than 40 towns and selecting candidates for the forthcoming elections to the united parliament. During the trip he received a copy of the union act passed by the imperial parliament and discovered that, in order to secure the support of Sir Robert Peel and the Conservative opposition, Russell had omitted from the act arrangements for the creation of municipal institutions and had agreed to alter the distribution of seats in Lower Canada to inflate the number of English constituencies. He told Russell bitterly that he would deplore those concessions “to the end of my life” and considered resigning. He was mollified, however, when he learned of his elevation to the peerage as Baron Sydenham on 19 August, and he declared his intention to “stay and meet the first Parliament.” He also learned that Russell had been compelled to modify his Clergy Reserves Act and allot to the Church of England what Sydenham believed was a “monstrous proportion” of the revenue derived from the reserves. None the less, after a personal appeal to the leadership of the Church of Scotland and to Egerton Ryerson, he remained confident of his ability to “beat both the Ultra Tories and the extreme Radicals” in Upper Canada in the forthcoming elections. He was less certain, however, of Lower Canada, where French Canadian leaders were determined to sabotage the union. Even after reshaping the electoral boundaries of Montreal and Quebec so that both would return representatives from the British commercial community, he predicted that the elections would be “bad” in the lower province, because French Canadians had “forgotten nothing and learnt nothing by the rebellion.” Sydenham therefore used the Special Council to secure passage of 32 measures that he knew the French Canadians would oppose in the united legislature, including one establishing municipal institutions and another a system of land registration long demanded by the British minority.

Sydenham proclaimed the union on 10 Feb. 1841, the anniversary of the Treaty of Paris (1763) and of Queen Victoria’s marriage (1840). He had visited Kingston in September 1840 to “patch up a place . . . to meet in the Spring” but, partly because of “a very distressing illness,” was unable to move there until May 1841. His governmental tasks included completing arrangements with the British Treasury for a loan of £1,500,000 to pay off the accumulated debt of the Canadas and finish public works such as the Welland Canal. Even more time-consuming and laborious was the “entire reconstruction” of the administrative departments. Complaining of “the total want of system and power in the conduct of Government, and of the defective state of Departmental administration,” Sydenham agreed with one of Durham’s most important conclusions: the colonial government had to be reorganized to give the executive more effective control over the assembly. In line with recommendations by Durham and with principles, reflecting British practice, laid down by Russell, Sydenham argued that “the Offices of Govt [should be] arranged so as to ensure responsibility in those who are at their head and an efficient discharge of their duties to the Governor and the Public.” Utilizing studies on Lower Canada commissioned by Durham, and on Upper Canada prepared by a royal commission established in 1839 by Arthur, he systematically erected a new departmental framework, reallocating functions among existing offices, particularly the Executive Council, the civil and provincial secretaries, the inspector general, and the receiver general, and creating new offices, such as the Crown Lands Department and the Board of Works. In July 1841 he announced the union perfected, with “Effective Departments for every branch of the public service.” Since, on his insistence, the act of union had given to the executive the sole right to initiate money bills, the new system created a more centralized and efficient form of government, but it also made essential the command of a majority in the assembly.

For more than a year Sydenham had been preparing for what he described on 5 Feb. 1841 as the restoration to the people of control “over their own affairs, which is deemed the highest privilege of Britons.” Elections were held in March and April. Sydenham carefully orchestrated the campaign, with the aid in Lower Canada of his military secretary, Major Thomas Edmund Campbell*, and assisted in Upper Canada by Murdoch, his other private secretary James Hopkirk, Draper, and Provincial Secretary Samuel Bealey Harrison*. He chose returning officers favourable to the government, issued land deeds to supporters and denied them to opponents, thus disenfranchising the latter, handed out promises of pensions and government patronage, browbeat recalcitrant officials into supporting the administration, and distributed polling-booths and troops where they would most benefit his sympathizers. In Upper Canada the collapse of the “family compact” party and the support of all reformers readily secured him a large majority. In Lower Canada, where the election was marked by considerable violence, he carried nearly one-half of the seats by appealing to the loyalty of the British minority, whose representation had been inflated by the act of union, and particularly by cultivating the business and Eastern Townships votes through attempts to repeal the imperial duty on grain and prohibit the entry into the Canadas of American produce. When accused by one Alexander Gillespie of interfering in the electoral process, Sydenham retorted: “If he means that I personally interfere he is quite misinformed, but the Govt. officials must try to get seats in Parliament . . . and they surely have a right to look after their elections.”

The victory was extremely precarious since Sydenham led a hodgepodge of anglophones from various political backgrounds. About one-quarter of them were officials amenable to executive discipline, but, without independents such as Malcolm Cameron* or Isaac Buchanan*, Sydenham’s administration could not retain the confidence of the House of Assembly. Moreover, a substantial proportion of members, many of whom had been selected as candidates by Sydenham personally, such as Stewart Derbishire* and Hamilton Hartley Killaly*, lacked political experience and had little influence in the legislature. Sydenham’s support, therefore, fluctuated wildly during the first session, convened on 14 June 1841. His bill establishing a single bank of issue for the colony went down to defeat, but on almost every other matter he “came off triumphant.” He embarked upon a general plan of public works, revised the local customs regulations, adjusted the currency, established elected municipal councils for Upper Canada, regulated the sale of wild lands, and created a system of common schools. Sydenham not only decided what measures to present to the legislature, but also, according to Murdoch, planned “the manner of introducing them, and the means of preventing or defeating opposition.”

Sydenham’s most serious adversaries were the radical reformers of Upper Canada, led initially by Robert Baldwin and Francis Hincks*. Although they had supported union, they were disillusioned by Sydenham’s clergy reserves bill, which they considered a “poor return” for their support, and by Sir George Arthur’s distribution of patronage. William Warren Baldwin had quickly determined that Sydenham would be “one of the feeble and useless ‘no party men’” and, since Sydenham had refused to head a unified reform movement, Hincks and Baldwin had sought to construct one in alliance with French Canadian reformers. On the eve of the meeting of the legislature Baldwin demanded that the Executive Council be reconstituted on a party basis, and Sydenham therefore dismissed him as solicitor general. During the session reformers repeatedly sought to embarrass the government, and on 3 September Baldwin tried to force a firm commitment from it to responsible government. Although Sydenham refused to bind himself to following the assembly’s dictates on every issue and continued to play a major role in shaping the policies and personnel of the government, his ministers increasingly functioned like a cabinet (as Sydenham himself described them) and indicated to the assembly that they would resign if they lost the confidence of the house. Sydenham, too, was aware that he could not “continue the administration of public affairs with honour to himself, or advantage to the people,” if his government was unable to retain that confidence.

Sydenham gave the impression that he expected his system to endure for at least a decade. In August 1841 he wrote to a brother that he would leave behind “a ministry with an avowed and recognized majority capable of doing what they think right, and not to be upset by my successor.” In fact, his ministry was on the verge of disintegration by the end of the first session. Without virtually unanimous support from the British majority, it could not survive, but to maintain that support, noted Colborne, now Lord Seaton, Sydenham had to act “the part of a divided Tory in the Lower Province and of a Liberal in the Upper.” As French Canadian opposition to the union diminished, the loose bonds of Sydenham’s coalition disintegrated, and the more natural party loyalties among the British reasserted themselves. A perspicacious Seaton remarked that no governor could retain control “unless the machine is constantly worked by an Artist as clever and unscrupulous as the one that contrived to secure the majority of the first session.” Sydenham did not live to see the collapse of his system. His health continued to deteriorate, and in July 1841 he submitted his resignation. He requested a gcb (civil division), which was awarded on 19 August. A few days after receiving news of the distinction and dissolving the legislature, Sydenham had a riding accident. A wound became infected, and on 19 September he died, in agony, of lockjaw. According to the Kingston Chronicle & Gazette, between 6,000 and 7,000 people “lined the road in dense masses” to witness his interment at St George’s Church on 24 September. The anglophone newspapers praised Sydenham’s “urbanity and condescension of manner,” and Egerton Ryerson undoubtedly spoke for the majority in extolling “the noble mind which conceived those improvements and originated the institutions which will form a golden era in the annals of Canadian history.” In private, “family compact” members such as John Beverley Robinson* denounced “that despicable Poulett Thomson” and predicted that “it will be long before the mischief can be remedied.” The francophone press, remembering “his crimes,” wasted little space lamenting the architect of what they saw as oppression.

Ryerson admitted that “the revolutions of time” were essential for “an adequate appreciation” of Sydenham’s government. Yet Sydenham has remained controversial. In the early 20th century anglophone historians generally praised him. The revisionists have been less kind; Irving Martin Abella’s Sydenham is “a ruthless Machiavellian, unprincipled and cunning, selfish and egotistic, autocratic, narrow-minded, and unbelievably vain.” The best that even the most sympathetic French Canadian historian, Jacques Monet, can say about him is that he was “gouty, impatient, and on occasion, for long weeks at a time, bedridden.” Undeniably, Sydenham found life in the colonies dull, and he had considerable disdain for those he had been sent to govern. When the Toronto Herald issued a sheet of doggerel criticizing him, he ordered “extra copies to be placed on his drawingroom tables for the amusement of New Year’s callers, to whom he read them himself.” Yet there is also abundant evidence of Sydenham’s personal charm and his charisma in attracting support from such diverse personalities as Ryerson and Hincks. Despite frequent illnesses, he did not neglect official duties; he once wrote that he would frequently “breathe, eat, drink and sleep on nothing but government and politics,” and he was responsible for more provincial legislation than any predecessor or successor. Many politically inspired measures – including the municipal incorporation acts, the Common School Act, and the language and judicial legislation – were subsequently amended substantially or repealed, but the administrative structure he created remained nearly intact during the union. As a former member of the British cabinet, Sydenham possessed unusual influence with imperial authorities. Thus he could force the Post Office Department to reduce postal rates considerably despite opposition from the deputy postmaster general, Thomas Allen Stayner*, and he repeatedly overrode efforts by the Treasury to reduce colonial expenditures. Although he believed that the imperial government must lay down the general principles regulating trade, he recognized “the great inconvenience” of its originating all changes and sought to give the local legislatures power to amend regulations. He was also fortunate in receiving the consistent support of Lord John Russell, who dominated the Colonial Office and the cabinet.

Most of Sydenham’s contemporaries assumed that he introduced responsible government, and critics such as Seaton argued that he had made it “impossible to resist the demands” of a majority in the assembly. The first generation of historians of Canada, notably John Charles Dent* and Adam Shortt*, accepted that view, but more recently Kenneth N. Windsor, Donald Swainson, and Ged Martin, among others, have disagreed. The revisionist argument, however, places too much emphasis on the refusal by Russell and Sydenham to commit themselves to the principle of responsible government. The London Colonial Gazette pointed out in September 1839 that, “notwithstanding Lord John Russell’s declaration against Responsible Government by that name, Mr. Thompson adopts the views of Lord Durham and accepts that the ‘administration of local affairs [must be] in constant harmony with the opinion of the majority of the representative body.’” Sydenham did try to resist recognizing what he called the “absurd sense” of responsible government, as put forward by Robert Baldwin, according to which he must follow the advice of the majority on all matters, but then no governor prior to confederation could make such a commitment.

Revisionists also criticize Sydenham’s intervention in the political process. His partisan use of the apparatus of state was, however, in line with British practice even in the post-reform era, although by acting as his own prime minister and party leader Sydenham involved the crown more directly than did the monarch in Britain or would Sydenham’s successors. To some extent, as Murdoch had declared, government interference was an inevitable by-product of Sydenham’s system of responsible government. So long as Sydenham worked through ministers responsible for his actions and supported by the assembly, nothing in his actions, however, was illegal, unconstitutional, or inconsistent with the basic principle of responsible government. And by the end of the session of 1841 that principle had become the established practice in the legislature of the United Province.

The charge that Sydenham wished to anglicize French Canadians is more accurate. He did treat them as a conquered race. Yet to condemn him for doing what he was sent to do is unreasonable. Certainly his objective was to make Lower Canada “essentially British, for unless that be done,” he felt, “it will be impossible to cultivate it’s natural resources, to improve the condition of it’s inhabitants, or to secure its permanent connexion with the Mother Country.” He thus encouraged immigration from Britain and sought to appease the Upper Canadians and the British minority in Lower Canada. The decision to establish the union had been taken by the British cabinet, and even with hindsight it is difficult to see any alternative method of restoring representative institutions to Lower Canada which would have been acceptable to the British inhabitants of both Canadas. In this sense, as Ged Martin has written, union was “dictated by the logic of events”; Sydenham considered “Anglification” an unavoidable consequence. Like most English liberals, he rejected notions of a multicultural society; as Janet Ajzenstat has argued, he believed that deep cultural cleavages prevent “the full realization of liberal rights” by leaving members of minority cultures vulnerable to exploitation.

Ultimately the union was not so disastrous to French Canada as its critics had predicted. French Canadians became a minority, but were numerous enough to defend their vital interests and secure enough to open a new era of collaboration with the anglophone majority. Without this imposed cooperation, confederation, which was not a feasible solution to the Canadian problem in the 1840s, might never have taken place. In this sense Sydenham deserves credit not only for preserving the British connection, which was the purpose of his mission, but also for laying the foundation of a more enduring and larger union. No governor had such a profound influence on the future development of the British North American colonies – not even Lord Durham.

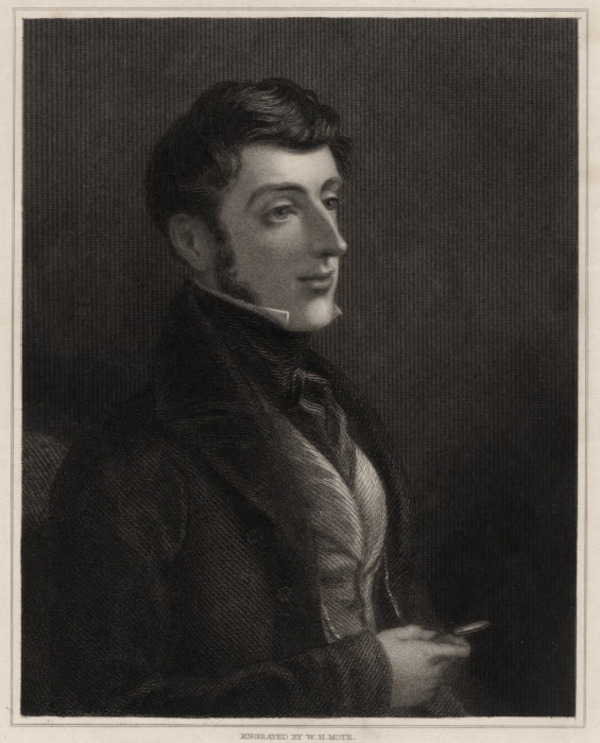

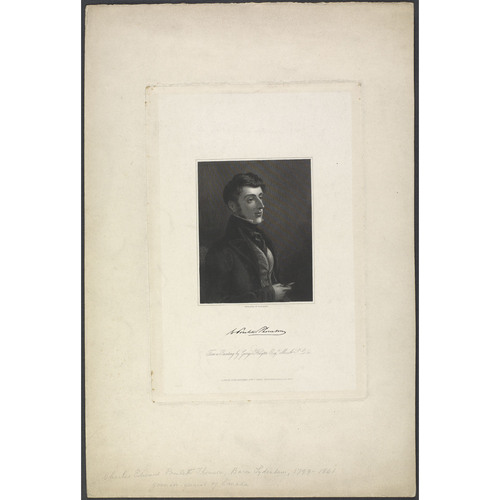

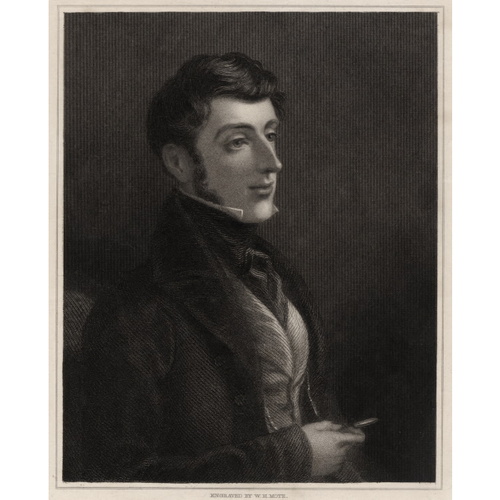

Some of Sydenham’s correspondence has been published as Letters from Lord Sydenham, governor-general of Canada, 1839–1841, to Lord John Russell, ed. Paul Knaplund (London, 1931). A portrait of Sydenham appears as the frontispiece to Memoir of the life of the Right Honourable Charles, Lord Sydenham, G.C.B., with a narrative of his administration in Canada, ed. G. P. Scrope (London, 1843).

AO, MS 4; MS 35; MS 78. MTRL, Robert Baldwin papers. NLS, Dept. of mss, mss 15001–195. PAC, MG 24, A13, A17, A27, A30, A40, B29 (mfm. at PANS); RG 5, A1: 6510–7022; RG 7, G14, 5–6, 8; RG 68, General index, 1651–1841: 72. PRO, CO 42/296–300; 42/446–76; PRO 30/22/3E–4B. UCC-C, Egerton Ryerson papers. Univ. of Durham, Dept. of Palaeography and Diplomatic (Durham, Eng.), Earl Grey papers. Arthur papers (Sanderson). H. R. V. Fox, Baron Holland, The Holland House diaries, 1831–1840, ed. A. D. Kriegel (London, 1977). C. C. F. Greville, The Greville memoirs: a journal of the reigns of King George IV and King William IV, ed. Henry Reeve (8v., London, 1874–87). Notices of the death of the late Lord Sydenham by the press of British North America . . . (Toronto, 1841). [John] Richardson, Eight years in Canada; embracing a review of the administrations of lords Durham and Sydenham, Sir Chas. Bagot and Lord Metcalfe, and including numerous interesting letters from Lord Durham, Mr. Chas. Buller and other well-known public characters (Montreal, 1847). Samuel Thompson, Reminiscences of a Canadian pioneer for the last fifty years: an autobiography (Toronto, 1884; repub. Toronto and Montreal, 1968). Three early nineteenth century diaries, ed. Arthur Aspinall (London, 1952). Colonial Gazette (London), 18 Sept. 1839. Novascotian, or Colonial Herald, 24 Oct. 1839.

Janet Ajzenstat, “Liberalism and assimilation: Lord Durham reconsidered,” Political thought in Canada: contemporary perspectives, comp. and ed. Stephen Brooks (Toronto, 1984), 239–57. Lucy Brown, The Board of Trade and the free-trade movement, 1830–42 (Oxford, 1958). Buckner, Transition to responsible government. J. M. S. Careless, The union of the Canadas: the growth of Canadian institutions, 1841–1857 (Toronto, 1967). Craig, Upper Canada. J. C. Dent, The last forty years: the union of 1841 to confederation, ed. D. [W.] Swainson (Toronto, 1972). S. E. Finer, “The transmission of Benthamite ideas, 1820–50,” Studies in the growth of nineteenth-century government, ed. Gillian Sutherland (Totowa, N.J., 1972), 11–32. Norman Gash, Reaction and reconstruction in English politics, 1832–52 (Oxford, 1965). J. E. Hodgetts, Pioneer public service: an administrative history of the united Canadas, 1841–1867 (Toronto, 1955). O. A. Kinchen, Lord Russell’s Canadian policy, a study in British heritage and colonial freedom (Lubbock, Tex., 1945). Ged Martin, The Durham report and British policy: a critical essay (Cambridge, Eng., 1972). Jacques Monet, Last cannon shot; “The personal and living bond, 1839–1849,” The shield of Achilles: aspects of Canada in the Victorian age, ed. W. L. Morton (Toronto and Montreal, 1968), 62–93. W. [G.] Ormsby, The emergence of the federal concept in Canada, 1839–1845 (Toronto, 1969). Adam Shortt, Lord Sydenham (Toronto, 1908). [G.] A. Wilson, The clergy reserves of Upper Canada: a Canadian mortmain (Toronto, 1968). K. N. Windsor, “Historical writing in Canada to 1920,” Literary History of Canada: Canadian literature in English, ed. C. F. Klinck (Toronto, 1967), 231. I. M. Abella, “The ‘Sydenham Election’ of 1841,” CHR, 47 (1966): 326–43. Ged Martin, “Confederation rejected: the British debate on Canada, 1837–1840,” Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth Hist. (London), 11 (1982–83): 33–57.

Cite This Article

Phillip Buckner, “THOMSON, CHARLES EDWARD POULETT, 1st Baron SYDENHAM,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 7, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 10, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/thomson_charles_edward_poulett_7E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/thomson_charles_edward_poulett_7E.html |

| Author of Article: | Phillip Buckner |

| Title of Article: | THOMSON, CHARLES EDWARD POULETT, 1st Baron SYDENHAM |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 7 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1988 |

| Year of revision: | 2021 |

| Access Date: | March 10, 2026 |