Source: Link

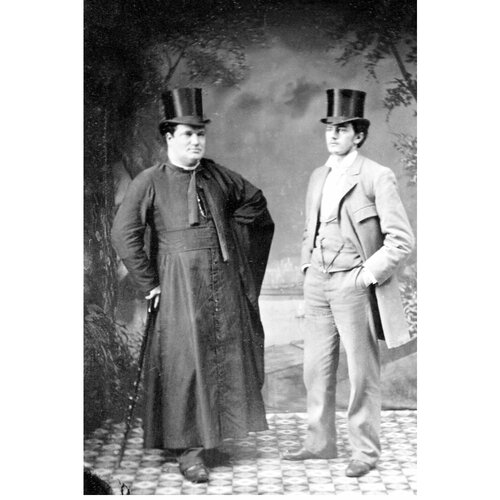

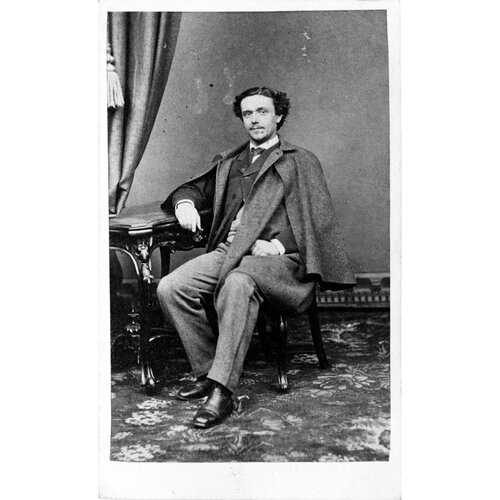

BUIES, ARTHUR (baptized Joseph-Marie-Arthur Buie), journalist, man of letters, and office holder; b. 24 Jan. 1840 in Côte-des-Neiges (Montreal), son of William Buie, a banker of Scottish descent, and Marie-Antoinette-Léocadie d’Estimauville; d. 26 Jan. 1901 at Quebec.

William Buie was living in New York at the time his son Arthur was born, but in 1841 he and his wife moved to Berbice (Guyana), where from 1842 to 1855 he held the office of postmaster. They left their son and their daughter Victoire, born in New York in 1837, in the care of two maternal great-aunts who resided at Quebec. Arthur Buies attended the Collège de Sainte-Anne-de-la-Pocatière from 1849 to 1854, the Séminaire de Nicolet in 1854–55, and the Petit Séminaire de Québec in 1855–56. When he was 16, he went to Berbice at the request of his father, who within a few months sent him to Dublin, agreeing to pay for his education there provided he pursued it in English. Young Arthur rebelled and went off to study on his own in Paris. From 1857 to 1859 he was a student at the Lycée Saint-Louis, intending first to complete his baccalauréat in science and later to study law at the Université Laval. He had four failures on his baccalauréat examinations.

Arthur’s break with paternal authority may have stimulated his taste for revolt against any kind of authority. From a financial standpoint it had serious consequences, for he had to live in straitened circumstances, which inevitably affected his studies. In addition, according to Abbé Thomas-Étienne Hamel, it was in Paris that Buies “got ideas,” and he was “quite capable of choosing the most perverse ones.” He abandoned all religious observance at that time and did not return to it until 1879.

In 1860, hounded by his creditors, Buies gave Latin and English lessons in Palaiseau, on the outskirts of Paris, and then went to Sicily, where he joined Garibaldi’s army. According to French journalist Ulric de Fonvielle, it was a comic-opera campaign, and Buies’s main activity was enjoying the food. In September he returned to Paris, where he eked out a living until in late 1861 or early 1862 he decided to come home to Canada, after an absence of six years.

Buies was no sooner back than he joined the Institut Canadien. He gave lectures, took part in debates, and served as vice-president in 1865 and corresponding secretary in 1868. He wrote for Le Défricheur, a newspaper recently established by Jean-Baptiste-Éric Dorion* and published in L’Avenir, and for Montreal’s Le Pays, of which Édouard-Raymond Fabre* had been co-founder. He threw himself into polemics, at which he came to excel.

In 1864 he had published in Montreal two Lettres sur le Canada . . . , which were an attack on the French Canadian clergy. In his view, “The clergy are everywhere, they preside over everything, and no one can think or wish anything except what they allow . . . they seek not the triumph of religion, but the triumph of their own dominance.” These letters (he would publish a third, in 1867) were meant also to denounce the backwardness of French North America in comparison with the English-speaking community of the continent and appeal to youth to shake off the apathy prevalent in French Canada. The author’s anticlericalism still left room, however, for a Christianity with more affinity to Protestantism than to liberal Catholicism: “I believe in God and in the sublime truths of Christianity, but I will not have you usurping my conscience, . . . I want to seek the truth that God himself has declared difficult to find.” Buies fully intended to carry on the radical tradition of the Institut Canadien and of “the brilliant pleiad of 1854 . . . the red pleiad,” as he would call it in his Réminiscences; Les jeunes barbares . . . (Québec, [1892]), the tradition of Joseph Papin*, Jean-Baptiste-Éric Dorion, Gonzalve Doutre*, Louis-Antoine Dessaulles*, and others.

In 1864 Buies also published two articles in Le Pays entitled “Le progrès,” which sang the praises of science. He took up his pen again many times the following year, writing, among other things, about the United States, which he defended against conservative attacks, and about the French language. In a series entitled “Barbarismes canadiens,” he pointed out numerous incorrect expressions current in the spoken language and the newspapers. “The unique character of each language must be preserved,” he urged, “and violence must not be done to it by introducing foreign expressions when it has words of its own that convey better the idea to be expressed.”

In “L’instruction,” written in 1866, Buies called for a twofold reform of the French Canadian educational system. He considered it essential for science to be taught at a much more advanced level in the schools. He also believed a non-denominational school system on the American model had to be established. He was firmly convinced that French Canadians would never rise above their inferior position until they had at least as much schooling as their English-speaking neighbours.

During this time, like some of his liberal friends, Buies fought against the proposed confederation of British North America, which finally came into being in 1867. That year he left Canada again, intending to settle permanently in Paris and make a career for himself there as a journalist. Having departed from Montreal on 29 May, he arrived in Brest by way of New York on 12 June. He published an article against confederation in a French magazine, became friends with geographer Pierre-François-Eugène Cortambert, and met George Sand. But, like Balzac’s Rubempré, Buies encountered fierce competition and once again experienced serious financial difficulties. His initial enthusiasm gave way to discouragement and by January 1868 he had returned to Montreal.

Buies was more active than ever in the Institut Canadien, where he continued to be preoccupied by educational issues. He also called for the abolition of the death penalty. Eager to continue the struggle against clericalism, he founded La Lanterne canadienne, patterned directly on La Lanterne, the Parisian newspaper of Henri Rochefort. From 17 Sept. 1868 to 18 March 1869, he wrote every week, on his own, some 15 vitriolic pages into which all his rage and his wit were poured. He had absolute freedom of speech since he was no longer speaking in the name of a party but in his own. He denounced not only his enemies, but also his friends, whom he considered too servile. “The only rogues are the decent people,” he remarked. The campaign Buies had embarked on was not aimed solely at clericalism and at the Montreal papers Le Nouveau Monde and La Minerve. In the third issue he proclaimed, “I can rest neither content nor easy in my mind as long as I see wicked men, fools, and cowards triumphing all around me.” This vast program enabled him to fire broadsides at the Conservative press, which, as a matter of fact, was no more indulgent with him. He sought to make people laugh with him rather than at him, but this approach did not prevent him from returning to the subject of education, which was particularly close to his heart. Denouncing the existing system, he asserted that “the young people come out of school crammed with pretensions but ignorant of science.”

Various pressures were brought to bear on the distributors of La Lanterne and soon the readership began to drop. That Buies held out for 27 weeks was indeed an accomplishment, for he was always alone despite an urgent invitation to young people to join him. He would retain a special affection for La Lanterne, and the paper assuredly has an important place in the annals of Quebec journalism. In fact, it remained a symbol of intellectual and moral courage at a time when many people had capitulated. In this sense, it was to inspire many talented journalists, for example Jules Fournier*, Olivar Asselin*, and Jean-Charles Harvey*.

Profoundly discouraged by the lack of support from his compatriots, Buies planned to go into exile again, first to Paris and then to New York. He went to Paris, but though by nature easily discouraged, he was also quick to take hope, and the following year, in Montreal, he founded L’Indépendant. Bilingual at the outset and later unilingual, the paper advocated Canadian independence and a republican form of government. “We all,” he wrote, “understand that we can have influence in North America only by personifying the French idea.” The experiment was of short duration, no more than a few months, and he moved permanently to Quebec, where he became a correspondent for Le Pays.

In later life Buies would reminisce nostalgically about these years of struggle. “We saw the last days of the old Montreal,” he said, “and we were the last of the old-style students. We were the final link between a dying society and a new one coming into being, of utterly different tastes, spirit, and kind.” In fact, they were years of intellectual and professional training. Giving lectures and writing articles enabled him not only to develop his talents as an orator and journalist, but also to clarify his vision of French Canadian society, which he thought would flourish only with universal schooling and strong scientific and technical education. In his opinion, the integrity of French Canadian culture depended on a thorough knowledge of French, which was threatened in Canada by the élites – lawyers, politicians, businessmen, journalists, writers – who were all doing their utmost to corrupt the language. Finally, true to the ideology of the time, like all Quebec intellectuals he believed that colonization would not only end emigration to the United States but also complete occupation of the land by French Canadians, thereby minimizing the effects of British immigration to Canada and making possible the exploitation of its vast natural wealth.

It was in 1871 that Buies began his career as a columnist, first with Le Pays, then with Le National (Montréal), and on occasion with La Minerve and L’Opinion publique (Montréal). Feature columns played an important role in the newspapers of that time. They were a mixture of current comment, news items, and personal titbits, all written in a bantering and humorous style. The columnist’s task was to entertain, to make readers smile, or even laugh. Buies’s spontaneous, ironic, and sometimes sarcastic wit was admirably suited to this kind of writing. He saw such a feature as “a weekly offering, suitably seasoned, more or less humorous, filling perhaps two columns on the page, sufficiently well done to help the reader relax and enable him to take in the formidable arguments of the other columns drawn up in battle array with all their cannon thundering.” But the feature had a more serious side, which could provide substantial food for thought about society, and for this kind of article Buies had a quite different definition: “What indeed is a feature but a day-by-day account of events seen at close range, intimate occurrences in which one is involved or which take place before one’s eyes, a fleeting and piquant glimpse of those little facets of the history of one’s time that historical criticism, to be serious, can now no longer do without?”

Buies published, at Quebec, three collections of his columns covering the period 1871–78: Chroniques, humeurs et caprices (1873), Chroniques, voyages, etc., etc. (1875), and Petites chroniques pour 1877 (1878). Ranging from election campaigns to seaside resorts, from philosophical meditations to accounts of travels, the contents of the three volumes are too diverse to summarize. The Chroniques lend themselves to random browsing in the mood of the moment. Perhaps more than conventional literary works, they remain irreplaceable as a documentary on the rapidly changing province of Quebec. Chroniques, voyages includes “Deux mille deux cents lieues en chemin de fer,” an account of a trip that Buies made to San Francisco in June and July of 1874.

It was during this period that Buies established himself as the leading columnist in the province. He regretted, however, that the genre gave him a reputation as a writer lacking in serious intent, superficial and unable to produce thoughtful works. Much later he would note in annoyance: “I know very well that you [the reader], at least, will not commit the excruciating banality of calling me ‘one of our wittiest columnists.’ For more than 20 years I have been harassed with this platitude. Upon my word, I have had to be a very witty columnist indeed (but not ‘one of our wittiest’) in order not to have as yet been intoxicated by that decoction of commercial aloe and adulterated myrrh at the hand of neophyte journalists.”

This was also the period when the Liberals came to power in Ottawa, and, as a faithful defender of the party for many years, Buies expected to be given a sinecure and to join his journalistic and literary colleagues who had already moved to the federal capital. But his attitude was not to the liking of the party élite and he had to persist in a profession that, by all reports, is one of the most thankless, both financially and professionally. As he later observed, “The French Canadian journalist is truly a wage-slave, a beast of burden, a convict at hard labour, a rock breaker, a cleaner of underwater cables.”

Certainly in September 1875, when Buies delivered a lecture published at Quebec under the title Conférences: la presse canadienne française et les améliorations de Québec . . . , he was still bent on reforming a vehicle he considered fundamental to the progress of French Canadian society. Indeed, as an heir to Étienne Parent*, he was convinced that men of letters had a mission to tackle, and that they would accomplish it through the medium of the press. Hence he attacked all those who, in his view, betrayed their mission and made the French Canadian press the most mediocre to be found in any western country. This mediocrity stemmed from ignorance of the language, which precluded debate about ideas, quickly reducing it to insults and slander. “And here is perhaps the greatest misfortune of our press,” he exclaimed, “that one is not allowed to express a free opinion in it without being immediately accused of heresy by a band of hacks as ignorant as narrow-minded and pretentious.”

The abolition of the Department of Public Instruction the following year by the Conservative government of Charles-Eugène Boucher* de Boucherville, with the consent of the Liberal mlas, infuriated Buies, and in May he founded Le Réveil. His fighting spirit of the 1860s revived and he rebelled against the legislation, which put education under the exclusive control of the Catholic Church. He made a violent attack on the clergy as a result of which the paper was condemned by Archbishop Elzéar-Alexandre Taschereau*. But Buies also denounced the opportunism of the Liberal party, “the party that represents nothing, that means nothing, that has not one principle expressed in any program, and whose motto, in power or in opposition, is invariably: Concessions, evasiveness, equivocation, indirection, temporizing, hypocrisy.” Forced to leave Quebec, the newspaper moved to Montreal in September and ceased publication in December. Le Réveil was Buies’s last attempt at independent journalism and some may think that his radicalism ended with it. It would be more accurate to say that, when he had to assume a lower profile in public life, he none the less remained true to his ideal of non-denominational education.

Buies’s activities during the period immediately after his return to Le National as a columnist in 1877 are not altogether clear. His correspondence with his friend Alfred Garneau indicates that in 1879, following a severe physical and mental breakdown, he again became a practising Catholic. “At last,” he explained, “I am out of the mire. I have not had such a feeling of relief [as I have had] from the day I received communion again, for the first time in 23 years.”

In June 1879, on the recommendation of curé François-Xavier-Antoine Labelle*, Buies was invited by the commissioner of crown lands, Félix-Gabriel Marchand*, to join his department. So began his career as a “colonizer.” In truth, his first article, entitled “Colonisation” and published in Le Défricheur on 19 Nov. 1863, had declared that “agriculture . . . is the essential foundation of our prosperity.” But his interest in colonization was inseparable from his enthusiasm for geography, which he described in 1875 as “the most indispensable science for anyone involved in writing for the newspapers”; from 1878 he was secretary of the Geographical Society of Quebec.

His appointment to the Crown Lands Department gave Buies an opportunity to write his first “geographical” work, Le Saguenay et la vallée du lac St-Jean; étude historique, géographique, industrielle et agricole (Québec, 1880). This kind of work corresponded perfectly to his ideal of “national literature.” As he often repeated, French Canadian writers must stop imitating French authors, and must choose subjects that are “Canadian” and, above all, useful. A few years later he would explain to François-Xavier Garneau*’s grandson Hector that “a literature that is not useful, that is not instructive, is a literature gone astray.” Thus he did not feel he was betraying his vocation as a writer by turning out monographs for his department or, later, for the Department of Agriculture and Colonization.

In 1881, after a visit to Boston where he met Francis Parkman*, Buies made plans to leave for New Orleans, but he delayed his trip because of the postponement of his marriage, which was eventually called off. That year he travelled through Quebec’s northern townships and the Ottawa valley, and published a series of articles in Le Nord (Saint-Jérôme). These activities did not prevent him from contributing to La Nouvelle-France, a bimonthly literary and scientific magazine founded in May at Quebec by his friend Jacques Auger. In his article, addressing himself to young people, he urged: “Study, study; knowledge is power. Be ready for all the discoveries, for all the elucidations of modern science. It is because we were caught unprepared by the prodigious development of science that we have remained on the sidelines, and outsiders have taken our place.”

The following year was marked by his contribution to Les Nouvelles Soirées canadiennes, a literary review founded at Quebec by Louis-Hyppolite Taché, Edmond Lortie, and Elzébert Roy. Buies also spent three weeks in December at Notre-Dame Hospital in Montreal, apparently because of alcoholism. Shortly afterwards, he was dismissed from his position by the Conservative premier, Joseph-Alfred Mousseau*. Commenting on the incident, Buies himself remarked, “I also tried to lead the government aside into undertakings that were at the very least uncertain, but after being knee-deep at the trough for two years, doing nothing, I was dismissed, along with some 30 other dolts whose services, after a long trial period, were considered unnecessary.” He was then forced to resume writing his columns, and his byline appeared on a regular basis in La Patrie (Montréal).

In the summer of 1883 Buies left for western Canada. He wrote an account of this journey in “Lettres du Nord-Ouest,” which appeared in La Patrie from August to November and this account was republished in 1890, at Quebec, under the title Récits de voyage. . . . In 1884 he reissued the 1873 collection of Montreal columns, under the new title Chroniques canadiennes, humeurs et caprices, and a new edition of his 1868–69 weekly, La Lanterne canadienne, under the title La Lanterne. He also proposed to reissue his two further collections of columns, but nothing came of his plans. In 1885 the Riel affair [see Louis Riel*] prompted him to publish the newspaper Le Signal (Montréal), which was intended to be “progressive.” Only one issue came out and in it he asserted, “Out of the Riel question will arise ‘unrest’ about many other questions that only recently still seemed impossible to discuss, and that will soon emerge as the natural and, in a way, inevitable corollary of it.” In 1886 La Lanterne was condemned by Archbishop Taschereau, who intervened personally with the Institut Canadien at Quebec to have a lecture by Buies cancelled.

A confirmed bachelor, Buies fell in love, and on 8 Aug. 1887 he was married at Quebec, in Notre-Dame basilica, to Marie-Mila Catellier, a daughter of Ludger-Aimé Catellier, the deputy registrar general of Canada. They would have five children. In May 1888 Premier Honoré Mercier* appointed curé Labelle assistant commissioner in the Quebec Department of Agriculture and Colonization. The following month Buies, who now had family responsibilities, became a colonization agent, a position he held until he was dismissed from his duties by the Conservatives in July 1892.

Buies had been a regular contributor to L’Électeur (Québec) since 1887, and in 1889 he finally published, at Quebec, L’Outaouais supérieur, a work begun at the start of the decade. Then four volumes came out in rapid succession at Quebec: Les comtés de Rimouski, Matane et Témiscouata . . . , a collection of three reports, and La région du lac Saint–Jean, grenier de la province de Québec . . . in 1890; Au portique des Laurentides; Une paroisse moderne; Le curé Labelle in 1891; and finally Réminiscences; Les jeunes barbares in 1892. This feverish activity went on despite the fatal illness of his first child and the death of Labelle.

In a remarkable article entitled “Le coup d’état Angers et la chute de Mercier,” published in La Patrie on 6 Aug. 1892, Buies attempted to explain the fall of the Mercier government. The former premier’s friends would never forgive him for his assertion that Mercier “had the best prospects that ever fell to the lot of a Canadian statesman: he had an entire people behind him and a glorious role to play: his vanity, his selfishness, his total lack of any moral sense spoiled it all.”

During the 1890s three children were born to Buies and his wife, two of whom died in infancy. His own health, which was in a delicate state, continued to deteriorate. Financial difficulties mounted, and he had to apply for assistance to the provincial secretary’s office, which bought a number of his books from him. After 1896 he also sought the support of his Liberal friends who were then in power in Ottawa.

His disappointments, however, did not get the better of his verve, and to those cherishing any illusion that they might see him disappear into the background in public life, he was scathing. His anticlericalism came out strongly in “Interdictions et censures,” an article published in 1893 in Canada-Revue (Montréal). “Let us bear in mind,” he urged, “that for more than 40 years the French Canadian people have suffered from an incredible outburst of ecclesiastical pretensions. Never has a lauding of such intolerance been witnessed.” In 1895 he briefly resumed his career as a columnist for La Revue rationale (Montréal) and published his last works on colonization, including a new edition of Le Saguenay et la vallée du lac St-Jean, under the title of Le Saguenay et le bassin du lac Saint-Jean; ouvrage historique et descriptif (Québec, 1896); Le chemin de fer du lac Saint-Jean (Québec, 1895); La vallée de la Matapédia . . . (Québec, 1895; 1896), and two commissioned works, one for the Department of Agriculture in Ottawa, Les poissons et les animaux à fourrure du Canada (1900), and the other for the Quebec Department of Agriculture, La province de Québec (1900). He had not lost his literary interests, however, and in Reminiscences; Les jeunes barbares he had condemned a number of young writers who, in his opinion, were taking it upon themselves to write without adequate knowledge of the French language, and he had made yet another attack on the educational system and the anti-intellectual climate in the province: “We are the most backward people in the world. . . . Any man in our little province who has succeeded in achieving genuine worth and a serious fund of knowledge has done so only by his own painful efforts, without any assistance, indeed, in spite of everything, and by overcoming all the obstacles heaped in his path.”

After an illness of several years, Arthur Buies died on 26 Jan. 1901. His remains were buried on 29 January in the cemetery of Notre-Dame de Belmont in Sainte-Foy, near Quebec. He was remembered as a kind and intelligent man who had spent his life trying to help his compatriots. From a literary point of view, he is considered among the best stylists of his time. He undoubtedly had one of the most inquiring and progressive minds in Quebec. He was convinced that the French-speaking community in North America ought not to live turned in upon itself but should be open to the great political, cultural, and economic currents of the day. His courageous attitude, his talent for polemics, and his critical mind were an inspiration to a great many intellectuals. Through his Chroniques and La Lanterne, he remains one of the outstanding figures of the Canadian literary and intellectual scene in the last quarter of the 19th century.

[Some of the correspondence of Arthur Buies is held at ANQ-Q, P-18, and has been copied in a typescript available in the Fonds M.-A. Gagnon at the Bibliothèque de la Ville de Montréal, Salle Gagnon. Two other important collections of his correspondence are currently in the possession of Arthur Buies Jr, Quebec (corr. with his wife and others), and Suzanne Prince, Quebec (corr. with Alfred Garneau). There is also correspondence in the following collections: AAQ, 31-17 A; ANQ-BSLGIM, fonds Ulric-Joseph Tessier (P-1); ANQ-M, fonds de la famille Papineau (P-7); ANQ-Q, fords François-Xavier-Antoine Labelle (P-124/217); Arch. de l’Univ. du Québec à Montréal, Fords C.-A. Dansereau (classification in progress); Arch. du Séminaire de Nicolet, Qué., F004 (J.-A.-I. Douville), succession; ASJCF, BO-78-28; ASQ, in the voluminous correspondence of Louis-Jacques Casault* and Thomas-Étienne Hamel (Univ., 39); AUL, P121, P137, and P209.1; Centre de Recherche en Civilisation Canadienne-Française (Ottawa), P 6/1/3 and P 263 (not classified); NA, fonds Louis Fréchette (MG 29, D40), fonds Alphonse Lusignan (MG 29, D27), Ponds famine Papineau (MG 24, B2), and fonds Benjamin Sulte (MG 29, D5); and the holdings of Francis Parmentier, Hull, Que. (copies of letters from Buies to Alfred Duclos De Celles, 26 Nov. and 29 Dec. 1898).

The author has published an annotated edition of Arthur Buies’s Chronigues . . . (2v., Montréal, 1986–91) and his Correspondance (1855–1901) (Montréal, 1993). f.p.]. AC, Québec, État civil, Catholiques, Saint-Jean-Baptiste (Québec), 29 janv. 1901. ANQ-M, CE1-51, 12 févr. 1840. ANQ-Q, CE1-1, 8 août 1887. DOLQ, vol.1. Raymond Douville, La vie aventureuse d’Arthur Buies ([Montréal, 1933]). Alfred Duclos De Celles, “Arthur Buies,” La Presse, 16 févr. 1901: 4. J.-C. Falardeau, “Arthur Buies, l’anti-zouave,” Cité libre (Montréal), no.27 (mai 1960): 25, 32. M.-A. Gagnon, Le ciel et l’enfer d’Arthur Buies (Québec, 1965). C.-H. Grignon, “Arthur Buies ou l’homme qui cherchait son malheur,” Académie Canadienne-Française, Cahiers (Montréal), 7 (1963): 29–42. Charles ab der Halden, Nouvelles études de littérature canadienne-française (Paris, 1907), 49–184. Léopold Lamontagne, Arthur Buies, homme de lettres (Québec, 1957). Edmond Lareau, Histoire de la littérature canadienne (Montréal, 1874), 463–66. Laurent Mailhot, Anthologie d’Arthur Buies ([Montréal], 1978). Francis Parmentier, “Arthur Buies et la littérature nationale” and “Arthur Buies et la critique littéraire,” in Rev. d’hist. littéraire du Québec et du Canada français (Ottawa), no.7 (hiver–printemps 1984): 57–59, and no.14 (été–automne 1987): 29–35, respectively. Virgile Rossel, Histoire de la littérature française hors de France (Lausanne, Suisse, 1895), 328–331. Marcel Trudel, L’influence de Voltaire au Canada (2v., Montréal, 1945), 2: 101–30, 152–60. J.-P. Tusseau, “La fin édifiante d’Arthur Buies,” Études françaises (Montréal), 9 (1973): 45–53. G.-A. Vachon, “Arthur Buies, écrivain,” Études françaises, 6 (1970): 283–95.

Cite This Article

Francis Parmentier, “BUIES, ARTHUR (baptized Joseph-Marie-Arthur Buie),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 7, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/buies_arthur_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/buies_arthur_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | Francis Parmentier |

| Title of Article: | BUIES, ARTHUR (baptized Joseph-Marie-Arthur Buie) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1994 |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | February 7, 2026 |